Meet Sharaya J, The Protégé Missy Elliott Has Been Carefully Cultivating For Five Years

The icon and her favorite rising rapper are on a serious mission to make music less serious

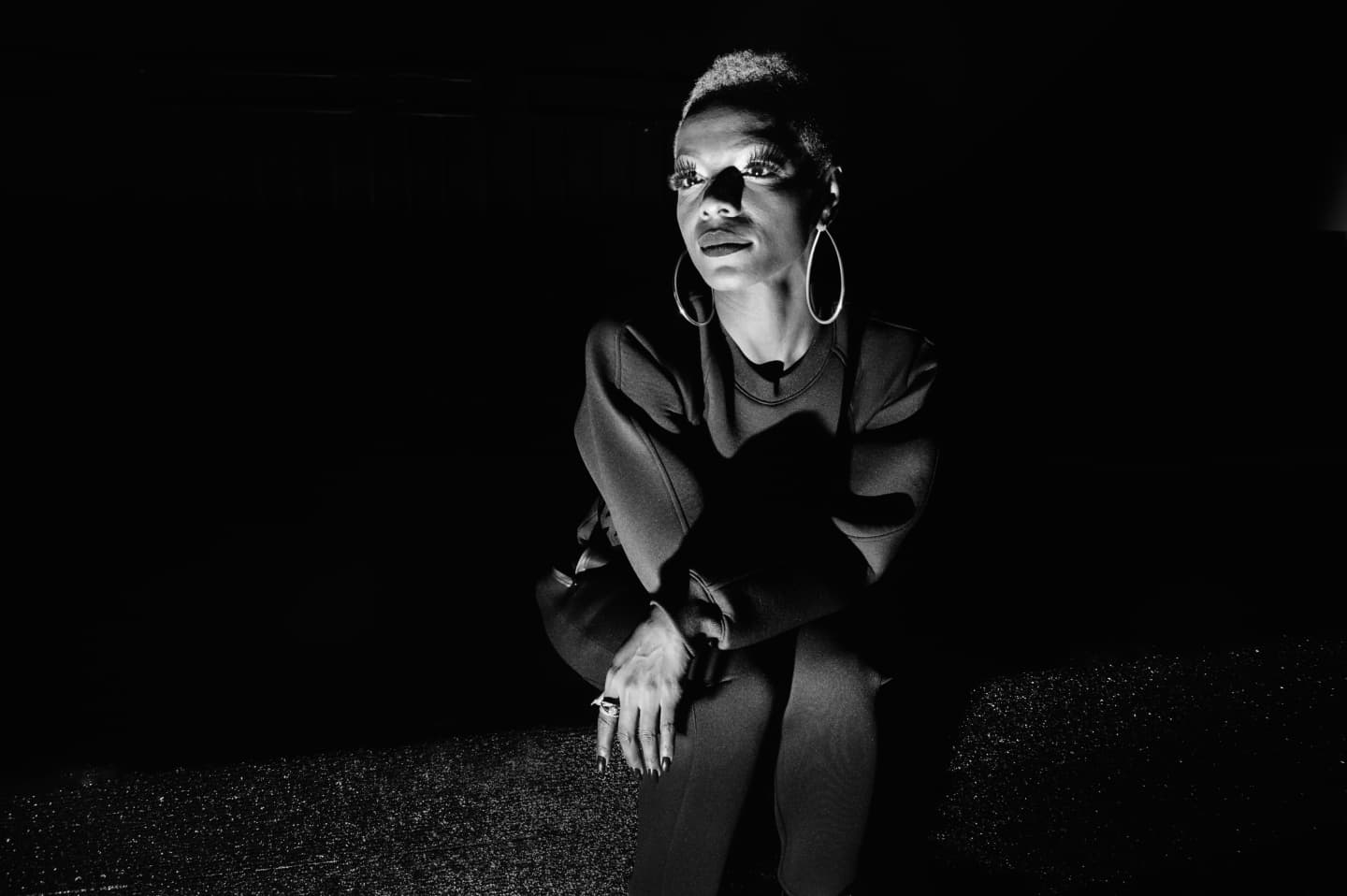

Even while wearing his signature black, Sharaya J can make Alexander Wang look Day-Glo. We're at the Harlem Armory after the runway launch of the designer's November H&M collaboration, and Sharaya—a 30-year-old rapper with a ready smile—is a bright contrast to the pale-faced models standing around her by the stage. Her Wang-emblazoned crop top is set off by a wedge of hair that must have turned several shades of yellow before it reached its current, neon-tinged blue. Her lipstick is a silvery navy.

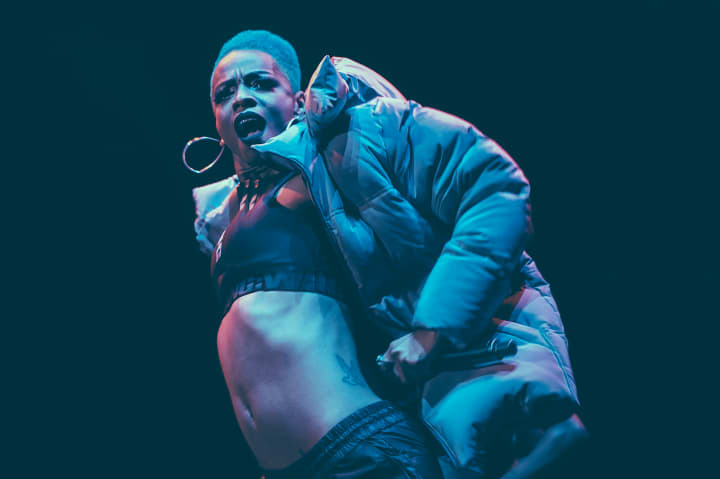

Tonight, Sharaya will perform three quick-witted, bass-rattled tracks for a crowd of curious fashion week onlookers. It won't be the largest stage that she and her Banji Girls dance crew have performed on. The New Jersey native has spent most of her adult life in the the spotlight, having toured with and choreographed routines for Ciara, Rihanna, and Diddy. In 2010, after meeting and befriending Missy Elliott at a dinner party thrown by mutual friends, she toured Europe with Missy as a dancer, and began performing some of her own music onstage, between Missy's sets.

Still, tonight feels like a coming out party; it's Sharaya's first time performing at a high-profile event as a solo artist and not as part of an entourage. When we come through you know we shut it down/ When we come through you know we shut it down! she sings, stomping along in time. Onstage, she seems like the crew leader of a band of lovable misfits, the Rufio to her dancers' Lost Boys. Their choreography is playful and athletic, more reliant on swaggy crew camaraderie than sexual innuendo. At the front of the group, Sharaya delivers her complicated footwork with a casualness that makes it look easy.

Missy is at the Wang show, too. She appears side-stage during Sharaya's set, and then jumps out for a surprise appearance of her own. Clad in a glittering, Wang-designed sweatsuit, her small frame is barely visible amidst her squad of backup dancers. "Did y'all come here to party?" she asks the sea of champagne glasses that toast her arrival to the stage. "Or did you come here to look cute?" She says it in a way that implies the correct answer.

"That's one thing Missy taught me," Sharaya says as she cools off with a fruity cocktail backstage after the show. "The audience can tell when you're being real with them. The audience can tell when you're having fun." In conversation, she speaks to me with the same familial warmth that she accords her Banji Girls, cracking jokes, laughing easily and often. For a moment, Missy appears. She hugs Wang before slipping out the back door to go to bed. "She doesn't need an after party," says Sharaya, who still talks about her mentor with a note of awe. "The audience should want to dance because they can't not dance with you. That's it. After that, your work for the day is done."

“The audience should want to dance because they can’t not dance with you. After that, your work for the day is done.” — Sharaya J

If it seems surprising that Missy would put energy into launching the music career of an up-and-coming rapper, it shouldn't be. The iconic lyricist and producer, now 43, has a history of fostering out-of-the-box female artists, famously helping to shape the careers of gospel-turned-R&B trio SWV, a young hat-tipping Ciara, the Swing Mob-affiliated Tweet, and most notably, Aaliyah. If Sharaya's so far gone less noticed than Missy's previous protégés, it's perhaps because Missy has been relatively absent from the spotlight in recent years. In 2008, she was diagnosed with the onset of Graves' Disease (an autoimmune disease that affects the thyroid), which forced her to slow down on work for several years. While she didn't speak about it then, she's opened up about it since, stating that refocusing on her health has further delayed the release of her much-teased seventh album, which is now a decade in the making. Since meeting five years ago, Missy and Sharaya have been traveling and working together almost constantly. Part mentee, part choreographer, and part fan, Sharaya observes Missy closely, learning from her in the studio and even helping her choreograph her Super Bowl performance. And Missy watches her, offering her expert feedback at every turn in Sharaya's new career. Sharaya calls Missy her "music mother."

Sharaya J. Howell was born in Hawaii but grew up in Jersey City. Her father was a part of New Jersey rap crew Double XX Posse, whose hit "Not Gonna Be Able To Do It" reached #1 on the Billboard Rap chart in 1992. "I started paying attention to the streets, to what people wanted to dance to, at a really young age," she says, referencing block party anthems by Salt-N-Pepa and Queen Latifah. "Me and my brother used to always write raps as a kid. I remember one of my very first ones was, I'm not sweet/ I'm not fine/ Let me tell you who I am/ You messin with Raya and you're gonna get slammed. It was for the haters!"

A few weeks after the Alexander Wang show, at a diner in Manhattan's West Village, Sharaya remembers sneaking out of her house as a teen to go to vogue balls in the city. "I grew up in the ballroom scene," she says, recalling that she first started learning about parties hosted by legendary vogue houses of Labeija and Xtravaganza at the age of 13. "I was very attracted to how creatively free [people in that community were]. When I saw someone vogue for the first time, I immediately wanted to learn the dance," she says. At 16, Sharaya joined the House of Labeija, participating in the Runway and Face categories. (Runway judges the style with which a dancer walks a catwalk; Face judges on the classic beauty of their face.)

Sharaya found a home-away-from-home in the ballroom scene, drawn to its celebration of self-described "ghetto girls" like her. "It was the realest," Sharaya says. "That's what 'being banji' came from, too." In the '80s and '90s, the slang word "banjee" was used by vogue communities to describe gay men who were intentionally ambiguous and androgynous in their style. Sharaya's understanding and repurposing of the word is non-gender-binary, free from sexual orientation, and is meant to serve as a broader platform for individuality. "Banjis never put on a show," she says. "They have a sense of humor about their situation, whatever it may be." The banji girls she met became the young Sharaya's confidants and dance partners, the ones she could "talk about boys, or work, or real life with."

When she wasn't hanging with her girls, Sharaya would hole up at home with her radio, listening to Jersey City's local club music and studying the lyrics of acts like Wu-Tang, ODB, and Lil Kim. One of her biggest loves was Biggie—as a pre-teen she recorded his songs off the radio while writing the lyrics into a notebook as they played. "I strived the most to write like Biggie, because his whole songwriting was next level," she remembers. "On 'One More Chance,' where he can throw in a crazy freestyle and then still give it that hook—that's how you make a record and tell a story, too."

Once they started working together, Sharaya found that Missy knew the importance of the qualities she had loved about Biggie: the attention to detail, the spontaneous but careful vocal nuance, the casually killer zing. But Missy, she says, was also a master at bringing stories to life. "Missy taught me how to be a character," Sharaya remembers. "She was a queen but also a clown; she took her art seriously but never herself too seriously."

“Missy taught me how to be a character. She was a queen but also a clown. She took her art seriously but never herself too seriously.” — Sharaya J

Missy's first memory of Sharaya is of her hair. "She had this hairdo where there was no hair in the back and a huge bang in the front," Missy tells me over the phone from her home in Los Angeles. "I was like, um, okay that's, uh, different." When the pair first met at that party in 2010, Missy says she was struck by Sharaya's "superstar quality." (Her family ties to Double XX Posse were an added bonus: "Tim and I used to play their record over and over," Missy recalls, referencing her longtime collaborator Timbaland. "We wore those records out!")

Missy invited Sharaya to record in her New Jersey studio immediately after that first meeting, but the offer came with a warning. "I said, 'I'll help you, but coming under me, it ain't gonna be easy,'" Missy remembers. "'The expectation is going to be high. You'll have to be writing every day, rehearsing or recording every day.' I wasn't going to just throw her out there. I come from an era where artists were groomed, so she shouldn't expect to just drop something out there tomorrow. That's how I've made hits before. I told her it was like boot camp."

With Missy, Sharaya worked on existing material and solicited new beats from local producers. A recording of "What About Love," the track she'd first performed on the string of Missy tour dates, was rubbery electroclash that took cues from Kid Cudi's "Day 'N' Night" and Chelley's cheeky "Took The Night." Early meetings with record labels—two years after Sharaya and Missy met, in 2012— went well, until some record execs asked Sharaya if she was willing to change up her look. "They asked me to put on booty shorts, heels, and put in a weave," Sharaya remembers. It was the exact opposite of her casually stylish preference for sweats, tights, and statement pieces, clothes that actually allowed her to move and perform her music. Missy could relate: "When I came out, I was totally different," the elder rapper recalls. "I was in a blow-up track suit and big shades, and I think people were confused. It took two or three listens or watching a few videos of mine for people to be like, 'Okay, I like this. This is different and refreshing.'"

Similarly, the pair now hopes that Sharaya's music will provide an ecstatic anecdote to oversexualized pop or the buttoned-up stuffiness of bottle-service clubs. On the phone, Missy speaks nostalgically of the '90s, when club music from Jersey, Baltimore, and Chicago crossed over with hip-hop and R&B. "People don't dance no more!" she laments, recalling the soulful, multi-faceted dance floors of yore. "When we were going to the club, we couldn't even hold a drink in our hand, because we'd be spilling it, because we'd be dancing!" She continues: "I've been to clubs in the last couple of years, and I'm like, something's missing. That's [the vibe] we knew we would try to recreate."

Sharaya's as-yet-untitled, forthcoming debut album is tentatively due out late this March via Missy's independent Goldmind label. She spent this past year tirelessly workshopping the project, and its sound is deeply indebted to Jersey Club. The production is aerobic enough for any dancer to dig into, with tongue-in-cheek builds and breaks that leave room for Sharaya's creative flows and hooks. "It felt organic and natural to me," says Sharaya, who adds that her debut will also feature more relaxed instrumentals. "It was the local music that I saw kids dancing to in the hood. It just felt right." Missy, apparently, is also a fan: "I love that kind of music," she says over the phone, humming the bam bam bam bam ba bam of the genre's booming basslines.

Sharaya's first official single, "Banji," released via YouTube in 2013, was produced by Jersey Club producer JayHood. (Jay sent beats for Sharaya over immediately after Missy reached out via Twitter DM, at Sharaya's recommendation.) Opening with a skit from the 1996 comedy Don't Be A Menace, it's a frenetic ode to Jersey City that big-ups her "banji babes"—a squad of her friends and dancers. In a seeming hat-tip to RuPaul's reinvention of the drag-throw-around "CUNT" into "Charisma Uniqueness Nerve and Talent," the hook of the song spells out "B-A-N-J-I," flipping the word into an acronym for her crew's slogan: "Be Authentic Never Jeopardize Individuality."

Several more Sharaya J songs were released in 2014, all with their own nostalgic references made to sound brand new. "Smash Up the Place/ Snatch Yo Wigs" is a sinister, minor-key production where a quick-tongued Sharaya wards off anyone who might step to her, ending with a Nicki Minaj-reminiscent, smirking freestyle over the instrumental to Bell Biv Devoe's classic "Poison." Then there's "Takin' It No More," a track that samples Missy and Ginuwine's 2001 collab "Take Away," admonishing cheating exes. Finally, there's "Shut It Down," an adrenaline-rush anthem that she can be seen performing in a promotional video for Wang's Spring 2015 campaign. (Coincidentally, the video for the song caught the eye of New York's Wilhelmina modeling agency. They signed her on to be a part of their roster in October 2014.)

So with five years worth of Missy-cosigned tracks and a rising fashion world profile, why haven't more people heard of Sharaya J? "That's easy," says Missy. "We're perfectionists." She is not using that word lightly. While Sharaya writes the songs and she and Missy generally agree on what beats to use, neither is satisfied until Missy has seen the song performed to completion. That means meticulously conceptualizing a video, choreographing dance moves, and making sure the song can be performed live, without any lip-syncing or sign of tiring. "I'm critical of everything," Sharaya says of her work. "When I perform I have to be able to dance and rap it live. That was the bare minimum you used to have to do back in the day!"

"There have been times when she's completely done with something and will show it to me and I tell her, 'You need to make it hotter! You need to bring something newer to the table,'" Missy explains. "She and one of her choreographers call me Missy Shredding-it. They say I'm always shredding whatever they do. But they know I know videos. And I know people want to see something they're excited by. That's what's going to have them running up to you to see what's next."

When it comes out, Sharaya's debut will be the first rap release that Missy has executive produced in full outside of her own. Sharaya says the project will include a collaborative track between her and Missy, called "Dope Product." "It's a back-and-forth between a teacher and her student," Sharaya explains, before rapping the hook: I ain't gonna rush for no dollars / I'm doing all this to deliver dope product.

"I don’t want [Sharaya] to fit in. I’ve always said that if you’re invited to a party and it’s an all-white party, come wearing hot pink." — Missy Elliott

Missy's is an old school approach to the music industry, one dedicated to ensuring that an artist's success is solid enough to withstand fleeting internet hype cycles. She knows trends fade as quickly as they come, hence her historical refusal to take part in them. "A single is easy, a single is different from a release," she says. She mentions that the current trend of self-released streaming EPs could possibly hinder an artist's creativity, despite the promotional benefits. "There's probably been 200 EPs released in the time that we've had this conversation," she jokes. "I want to make sure every track is a single that can stand on its own. I have 20 years of experience making albums full of stand-alone singles."

This might be her most crucial piece of wisdom as a mentor: the importance of having the time and freedom to be able to cultivate one's sound independently of the market one is sold into. But while Missy's track record of success as an artist and producer is nearly flawless—her credits appear on formative tracks by SWV, 702, and Jodeci, predating her work with Aaliyah—there's no denying that the music industry and radio play have gotten harder to navigate in the last decade. When asked whether she thinks that she can break Sharaya as a brand new artist—one who pairs throwback hood rap aesthetics with outlier, regional club sounds—into today's pop radio mainstream, Missy hesitates only for a split-second. "People don't know that Aaliyah's One In A Million was really hard to get played at first. Because DJs said the rhythm was off in the melody and that they couldn't understand it."

More importantly, Missy continues to stress the importance of collaborating with and supporting rising female talent. "These artists who are women need to keep raising each other up," she says, emphatically. "And making music that makes them feel good, too. I've always felt that and have looked to do that myself." Via email, Ciara concurs with her former collaborator: "[Working with other women] is powerful," she writes. "I am a 'girl's girl,' and it is necessary for me to always express that in my music. "There can never be enough women supporting other women."

Sharaya's crew of Banji Girls is perhaps the perfect example of that unity. "If women band together and get on a record together, that's a big statement," Sharaya says, adding that she hopes to do a track that brings a roster of "up next" women together. "It would be dope to do something like [Lil Kim's] 'Ladies Night' part two," she says. Sharaya knows that people want to dance, and so she makes music for women who go to the club to actually have fun, without having to look cute for anyone but themselves. "I know for sure that we need to start dancing again," says Sharaya. "Dancing and music have been the same for me, since the beginning. It's a way to express yourself, to get away from problems, to just be real and work it all out on the dance floor with your people."

Missy agrees. "It always took away from anything else that was going wrong with our lives," she remembers of her own coming of age, talking about the dance floor like a community-wide confessional. "We would go to the club and dance and dance and dance until we sweated our weaves out. Our hair would be messed up like something else, but we didn't care because we were in the moment." That no-fucks-given attitude that has been at the core of Missy's entire repertoire is also at the forefront of Sharaya's. "I don't want her to fit in," says Missy. "Twenty years later and even I don't fit in. I've always said that if you're invited to a party and it's an all-white party, come wearing hot pink."