When I was 18 and started putting on concerts at my college, the first one we booked was Diplo. The school was a few miles outside Philadelphia, where he had made a name for himself as one half of the DJ duo Hollertronix. At the time, his groundbreaking mixtape with M.I.A., Piracy Funds Terrorism, was just a few months old. I was obsessed with the internet-fueled idea that there were no longer any boundaries in music—Baltimore club remixes of new wave, Bone Crusher into baile funk. I thought mashups were meaningful, and he was basically my hero. I remember walking up to him, in our makeshift backstage behind the school cafeteria, and telling him, “I just wanted to say thanks.”

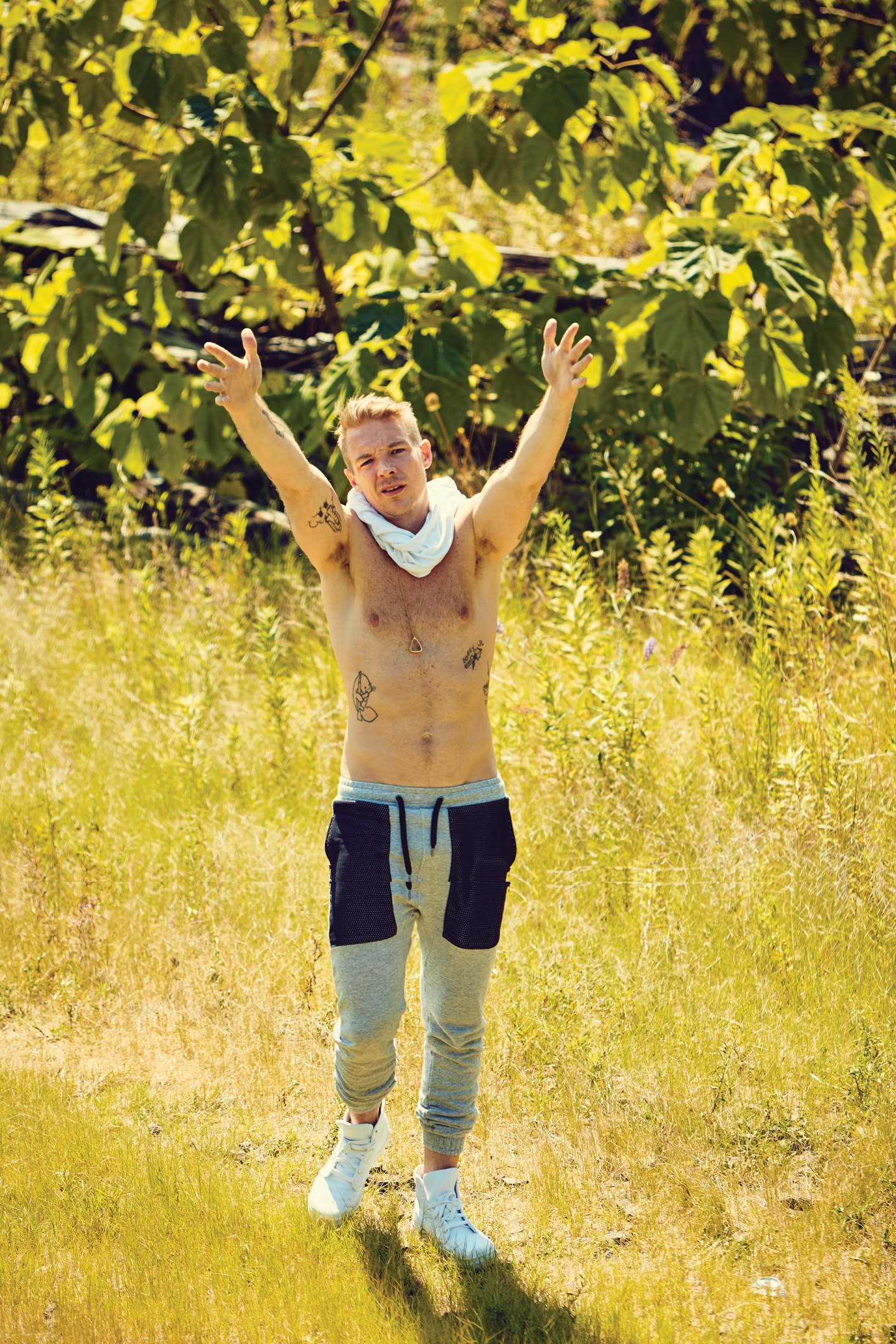

When I called Diplo for this interview, I recounted that story with requisite embarrassment, and the 36-year-old DJ and producer born Thomas Wesley Pentz laughed and said, “Not a lot of people thank me anymore.” While his love for global party music—and deftness at repurposing it for his own gain—made him one of the past decade of pop music’s most prescient figures, it also made him one of the most reviled: a white guy on a world safari. Diplo has often been his own worst enemy, whether he’s mouthing off about Taylor Swift or missing a meeting with Beyoncé because he’s locked up after a bar fight. But in all of this, he’s also proven unsinkable.

These days, Diplo has not only outlasted many of his critics, but ascended beyond their reach. His aptly named 2014 compilation, Random White Dude Be Everywhere, featured a mockup of his Twitter account showing 7 billion followers—a world’s worth. He runs a successful label, Mad Decent, and he’s done beats for Chris Brown, Snoop Dogg, and Madonna, alongside more free-spirited work with his groups Major Lazer and Jack Ü, both of which released platinum singles in 2015. He isn’t playing cafeterias anymore; he’s arguably the world’s most in-demand DJ. With that in mind, we discussed his rise, endurance, and what his teenage self would think of him now.

How did you make the transition from being a local party DJ to having music as your full-time job?

When I was younger, I didn’t know anybody who made a living as a DJ. I just couldn’t imagine it. Nowadays, kids can put a song on YouTube, and they’ll have the biggest presence. So back in Philly, I was doing everything I could do, making a little bit of money from a nine-to-five, renting out little VFWs, and doing DJ gigs. I was like, “I’ll be a writer, I’ll be a filmmaker.” I didn’t have any real goal.

When I look back at pictures of Hollertronix, I see nobody dressed cool. It was like there was no word “hipster” yet. People were wearing the clothes they went to work in, or they were coming from University of the Arts. Eventually, we got people who were like, “Oh, I want to do this party in New York City, I want to do this party in San Francisco.” They paid me to fly, and I had no overhead.

When that started taking off, all I did was put my money towards bad investments like Mad Decent and the Favela on Blast documentary. It was about five years before we broke even with Mad Decent. I was spending between 10 and 50 grand a year just to pay people’s salaries to stay at the label to work. In the end, those were great things to spend money on, but back then everyone said, “What are you doing?” Over time, I learned how to market myself better. We broke even with Mad Decent, then started making money. And the whole time that I was traveling around DJing, I was learning how to produce records. I literally learned from start to finish how to make music in the last 10, 15 years.

Now you’ve got songs on the radio, but it seems like you’re not DJing any less.

No, it’s definitely busier. I just think that my time is managed a lot better now. This year, between Diplo, Major Lazer, and Jack Ü, and all the different acts, it’s probably a good 350 shows with after-parties and stuff like that. Maybe two, three shows a day.

What is this calling that makes you want to play so many shows?

It’s not really a calling. I think that it just works. Touring Major Lazer marketed the project, and it’s a really hard project to market. Like, what is it, three guys that DJ together and make music? With Mad Decent Block Party, I’m the guy who’s headlining most of them in one way or another, and that helps to increase the value of it. I just did one, two, three, four, five, six shows between Thursday and Sunday. That sounds really dizzy, but it wasn’t that bad. I did press all day long yesterday, then today I’ll be in the studio after this conversation. It’s just a matter of managing your time. I know my time will run out soon, so I’m gonna try to do it as much as I can.

“I’m just a little shitty-ass redneck kid that’s making music with Madonna.”

You’ve said before that you’re an easy target for criticism, as a white guy working with a lot of people of color.

I don’t really know what music I’m supposed to do. The first person I produced music for was M.I.A., and her music was basically a hodgepodge of everything, culturally. It was dancehall, it was R&B, it was punk—I just thought it was our music. I never thought for a minute, like, “What did it mean?” And that experience was my training ground for when I worked with rappers, or with Baltimore club music, or with the baile funk stuff. I’ve produced records for 2 Chainz. I did stuff for Skrillex’s project. I worked in Jamaica with Popcaan and Kranium. When I go to Jamaica and do shows, 10,000 Jamaicans will go and say, “Yeah, we’re fans of Major Lazer.” I’ve done Korean pop records. To this day, I don’t know what white music is. I influence people and they influence me. It’s always a conversation back and forth with people.

Where did you get these ideas about production, the back-and-forth?

At the end of the day, I’m a DJ. It sounds silly, but people like Afrika Bambaataa are my heroes because nobody was doing what he did before he did it. No one told him you can’t play Led Zeppelin. This was a guy who was mixing German records, rock records, electro records, and making his own records out of all that didn’t exist beforehand. I loved DJ Premier, DJ Shadow. I loved groups like The Pharcyde, Wu-Tang Clan. Stuff from my middle school days really inspired me, like hearing Brand Nubian sample a slowed-down guitar. I was like, “Wow, there’s no rules to hip-hop at this point.” I was raised on dancehall too. I loved this guy named Lenky, who produced the Diwali riddim for Sean Paul. He was sampling little bits and pieces of culture, like Indian music or Western soundtracks, or soft rock guitars. I just loved the idea of anything goes. Who fucking cares? All this shit could get thrown into a pot and make something amazing.

It seems like your process is partly about finding something you can sell. Is that how you approached working with Justin Bieber? He wasn’t doing so hot before “Where Are Ü Now.”

For one thing, you’ve gotta understand that the music industry is different than the critic industry—the writers and the people that are talking about what is on trend or whatever. When you’re doing music, you’re always on trend or off trend, and it’s important to show people respect no matter what.

I met Bieber a few years ago, producing a record for him with Ariel Rechtshaid called “Thought of You.” I’ve known his manager, Scooter, for many years—he used to manage Kelis. They showed me respect back then and were really nice to me, so I always just kept them within arm’s length. They trusted me when I asked for a vocal. It was like a no-brainer. They had hit a place where nothing was working for them, and Justin had kinda hit rock bottom with things, like from the press, from jail, and from, like, taking his pants down at an awards show or something. I wasn’t even paying attention, but I know that he wasn’t very cool. And I was trying to really help Skrillex rebrand his own project, too. If nothing else, I thought working with Bieber would be the most noticeable thing we could do. It would be a great record, and it would make everyone really fucked up. It would make them really disappointed in themselves, and really confused, like, “How do I like this record?”

Even from day one, as I started to develop, I saw people’s perceptions of me as a producer, and they always want to put me in one box or another. Maybe that’s why I’m a target for things, because I don’t belong anywhere. If I make a record that makes people think that Justin Bieber is cool and makes them dance to it—which seems to be one of the most daunting tasks ever—then maybe people will rethink the way they think about music, you know? It’s not so dry and clear, what’s cool and what isn’t. Good music is going to be good music. He’s somebody you don’t want to like, but you like it.

To some degree, you’ve had to work against your own personality, too, at least how you’ve acted on Twitter, right?

I don’t use Twitter to be obnoxious as much as I used to. I never considered Twitter to be anything more than just a joke for 10 years, then all of a sudden it was a news source for people. The fact that I even became peers with people like Taylor Swift and pop stars, like, I never could even fathom that those people would look at my Twitter and be affected by it. That’s when I realized I was disrespecting my records. Now I’m trying to put all of my energy toward music positively, through doing the right videos and doing the right shows and doing the right artwork and viral things we can do. Just being obnoxious on Twitter only gets you so far, and then people don’t take your music seriously.

You’ve also been described as an anthropologist, both in a good way and a bad way.

You know, I went to school for anthropology, at Temple University. It was probably the worst major you could ever get. I ended up dropping out, but I took advantage of everybody and everything that I could in that place. I always felt like an anthropologist, and when I used to have to get people to write about my music, that actually worked in my favor—like, “Oh, this guy is doing Brazilian stuff.” The images were exciting; the music was exciting. I knew it was the way to get people to write about me, and I just used the critics to my advantage. Now, critics are into you one day and not into you the next day. I haven’t made music for critics in a long time. When they turned on me, I was already big enough to make music for fans, and I don’t think my fans give a shit about anthropology.

The very idea of local scenes has really changed, too.

In New York, you used to have a rap sound and a rap scene. Now it’s just like people are imitating Memphis rap or doing, like, Philly rap. The internet created—I can’t believe Fetty Wap is from New Jersey. I didn’t know where he was from. I heard him talk, and I’m like, “Oh my god.” Everything is a mashup now, you know? You don’t really know what is coming from where. Your favorite rapper might be from Ghana. The world has changed where nothing is as cut and dry. This is black, and this is white; this is from the South, and this is from the North; this belongs to Europe. Those rules are broken down, and I’ve always been an advocate of that, so I think I’m one of the guys who is able to take advantage.

A few years ago, you told Interview, “When I was 15 I used to run around reading Adbusters and dumpster diving, trying to find ways to make the U.S. government unwind into chaos through hardcore punk and metal.” Do you still feel like that kid?

Well, the thing is, like—this is important. I lived in Daytona Beach. My family is from there. Daytona Beach has no culture—like, no youth culture, zero. The only thing that we had was a Barnes & Noble. I would go in the coffee shop there and read magazines and, like, Howard Zinn books. I was a real counterculture, anarchist kid. That was just me and my growing pains. But I always kept friends from that world and that era. In Philly, the underground scene really helped me become who I am. This one guy, Cullen Stalin, who owns an anarchist book store in Baltimore now—I give him some money every year and invest in his bookstore. I was in Europe when the Baltimore riots happened, and so I talked to him on the phone about it. Guys like him keep me sane. They think what I’m doing is an extension of punk rock because I’m just a little shitty-ass redneck kid that’s making music with Madonna. It’s almost like a joke to them, like I’m in disguise. I’ve never lost track of that.