Alex Basse

Alex Basse

Halfway through my conversation with Dougie Poole late last year, I asked if he’d seen “Colonel Homer,” the episode of The Simpsons in which Homer winds up managing a country singer called Lurleen Lumpkin. In particular, I wanted to know if he’d watched the scene that introduces Lurleen to the viewer, in which, at a run-down dive bar way out of town, she sings a song called “Your Wife Don’t Understand You.” Homer hears every word of it (“You work all day for some old man / Sweat and break your back / Then you go back to your castle / But your queen won’t cut you slack”) as if Lurleen is talking directly to him.

Dougie Poole’s vision of country music is different from Lurleen Lumpkin’s. Though he still loves Willie Nelson and Emmylou Harris, and gleefully absorbs country radio, his sound is softer and more psychedelic than that. His lyrics don’t engage with material country tropes either; he’s a born-and-raised New Yorker and he doesn’t pretend otherwise. Still, there has always been something distinctly country about the way Poole writes, the specificity of his songs, his honest renderings of day-to-day depressions. There’d be no point in Poole playing at Silent Barn in Brooklyn, where he built a community early in his career as a singer-songwriter, and borrowing something from Lurleen Lumpkin’s line about flipping your pick-up truck “right off the Interstate.” Instead he’s written songs like “Vaping on the Job,” which is about what it says it’s about, and “Los Angeles,” about deciding to leave New York for California and then quickly giving up on the idea.

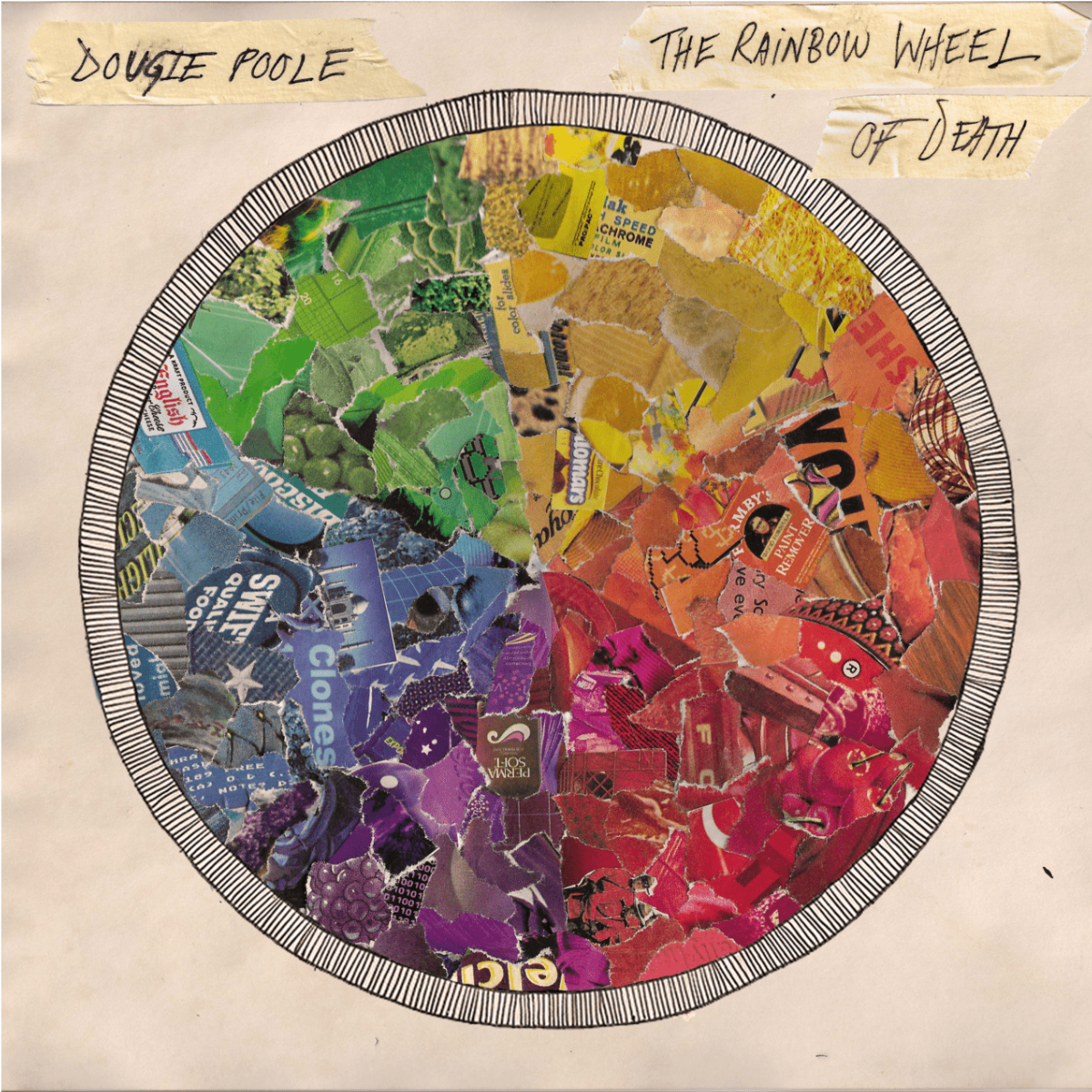

Poole’s new album, The Rainbow Wheel of Death, may not nod as frequently to those hallmarks of the city-dwelling millennial’s day-to-day (save for its title, a reference to the spinning cursor on Mac computers that suggests imminent doom). But the sensibility remains. Poole is self-deprecating and anxious, a “worrying man” who can’t raise a smile and seems to run from one heartbreak to the next. He seems more comfortable in his sound too, nodding to Springsteen on the grief dream “High School Gym” but elsewhere naturally falling into a sound more reminiscent of the outlaw and stoner records he loves. At his most poetic, there’s something of Gram Parsons about Poole, a melancholy psychedelia that’s at once starry-eyed but totally of this world.

This Q&A has been edited and condensed from an episode of The FADER Interview live on Amp.

You grew up in New York, a long way from the country music heartlands. Was country music around you at all growing up? Did your parents listen to country?

Not so much country as folk music and country-adjacent things like bluegrass — the cousins of country. I think part of what’s going on here with my connection to it is my dad is from the Appalachian Mountains in Pennsylvania. My mom is from Brooklyn and grew up in Brooklyn; she liked Simon and Garfunkel and the Mamas & the Papas stuff. But with my dad, there was always an appreciation for, if not country music itself, American folk music and storytelling.

When did you start listening to country more carefully?

It was a gradual thing. In my early twenties I was in a noise-rock band with some of my best friends. I kept bringing songs to rehearsals, and it just wasn’t fitting in because they were all real songy songs. I also studied creative writing a bit, so I had some experience with short story writing, where you have to think a lot about the economy of words. Country music feels like a version of that. It has a lineage, so there are rules and a history to tap into — which means there’s rules to break. It seemed like a good jumping off point.

“At this point, writing and composing music feels like doing whatever I can to get out of my own way. I want to turn off all the filters that keep me from working.”

There’s a distinct difference between The Freelancer’s Blues and The Rainbow Wheel of Death. The Freelancer’s Blues quite clearly dealt with day-to-day life for someone of a certain age and maybe even class. I think it was, for a lot of people, very precisely relatable. Was that intentional?

I don’t know how conscious that was. I was trying to write songs about my experience and the experience of people I knew. In a sense, I’m also a big-time apologist for contemporary country radio. I think there’s actually a lot of great songs on the radio, and my bandmates disagree with me. But yes, I guess that sort of approached words and structure and topics in the same way that the country music I like does.

But I don’t even know what deliberate means at this point. At this point, writing and composing music feels like doing whatever I can to get out of my own way. I want to turn off all the filters that keep me from working. So, in that sense, it was very non-deliberate.

Aquarium Drunkard described you as the patron saint of millennial malaise, and I think I’ve written something similar at one point or another. Is it gratifying for you to read stuff like that, to have that record treated that way? Or can it be frustrating as well?

That’s obviously validating. It’s part of releasing music, and I feel resigned to it. Also, those are mostly positive things people are saying. I think I would feel different if the reception were not “patron saint” but something a lot less generous. So I feel grateful that people like it. And while it’s not how I would always describe my own work, I feel fine about it.

“High School Gym,” the first single from the album, took a very different approach sonically. It’s clearly influenced by Springsteen; you’ve got this synth running through it, which you might have used before in a softer, more ambient, even psychedelic way. How has your relationship with the synth changed over time and through your career?

A lot of stylistic choices come out of necessity. What I really wanted on my first record was a pedal steel guitar, but I didn’t know anyone who could play one — so I just sort of did my best to approximate it with the synthesizer. Now my relationship with the synthesizer feels less based on necessity; I can pick and choose where I use it more.

It’s also a weighty song, about a dream you had where everyone you’ve lost is gathered together in one place. You might have broken that sort of weightiness up with humor before, as you did on a track like “Los Angeles.” You don’t do that here. Is that difficult to write? Is it difficult to reveal that much of yourself?

No, I don’t think so. I think humor comes in naturally when I try to write [in] detail — and I think detail is what people will latch onto in a song. The dream in the song, it came ready made with most of its own details. The hard part of it was figuring out how to squeeze the image and the feeling into a rock ’n’ roll song. I think I’m getting more comfortable, and maybe part of the humor dropping away is I’m getting more comfortable with myself as a songwriter. It’s sort of like the synthesizer thing; I don’t feel like I need to fill the space with jokes. It feels like something I can sprinkle in more deliberately rather than having it as a necessity to feel comfortable.

Almost like you’re losing a layer of armor.

Yeah. It’s a device, and you either cling to it or you don’t. I used to cling to it more than I feel the need to now.