AFP / Getty

AFP / Getty

Muhammad Ali, the awe-inspiring boxer who died June 3 in Arizona at age 74, was a man concerned with aesthetics. A sportsman of grace, he found beauty in fighting, beauty in winning, beauty in his pro-black politics, and beauty in his people. In the course of Ali’s lifetime, he bore many titles — son, father, traitor, brother, activist, antagonist, brute, nigger, paramour, egoist — though none greater than Champ.

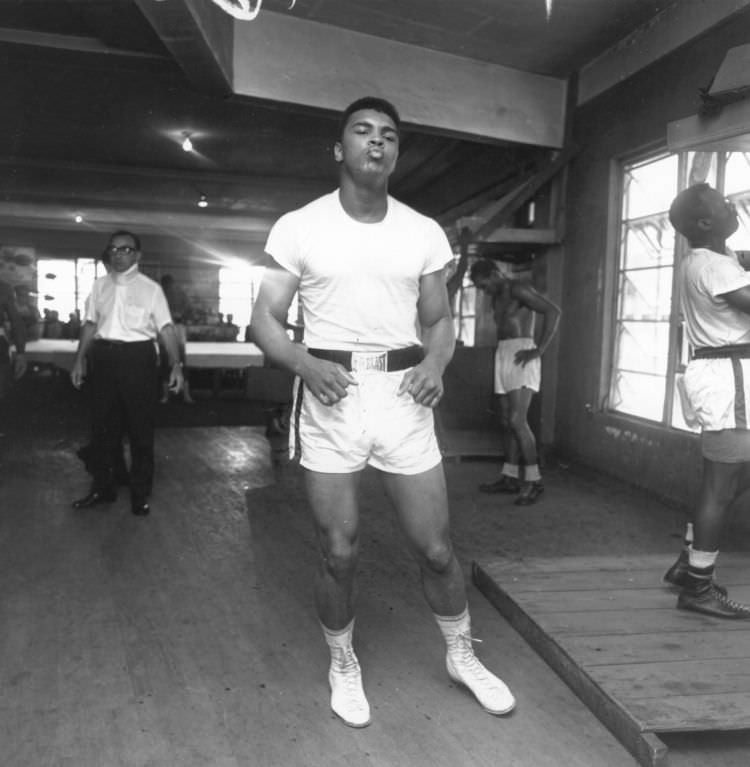

The roadmap of his existence was defined by peaks and valleys, what felt like near-constant controversy, and flashes of sweet, honeyed brilliance inside the ring. In the winter of 1942, some 80 years after slaves were first freed from the Confederate South, he was born in Louisville, Kentucky under the name Cassius Clay. Later, he assumed the moniker Muhammad Ali — one who is worthy of praise — after befriending Malcolm X and joining the Nation of Islam. A three-time world heavyweight champion, Ali became a symbol of black pride during the ‘60s and ‘70s for his pro-working man, anti-war politics and religious beliefs. He was a singular American fighter, a symphony of quick wit and devastating jabs.

Watching Ali go toe-to-toe against his rivals was like watching fire: a combustion of pure skill, hard work, melodic footwork, and intelligence that forced opponents like Joe Frazier, Bob Foster, and George Foreman into surrender. Outside of the ring, he was an unrelenting critic of the U.S. government, which commonly rejected the well-being of black Americans. Equality remained a fantasy for blacks during his early days as a fighter; the Voting Rights Act wouldn’t arrive until 1965, the year Ali defended his title against Sonny Liston in a rematch that lasted less than two minutes. Whether through questioning the parameters of whiteness or by simply uttering “I’m a bad man” he dared you to believe in him, to love him, to worship him. Even in defeat, which arrived so little that he became unaccustomed to it, Ali was unparalleled. He was an exclamation. A denunciation of all that chained black prosperity. He was, as writer Alex Haley called him, “sports’ most controversial cause cèlébre.” Ali was unbowed — at all times, Ali was unbowed.

“It isn’t enough that he is a fine fighter, unfortunately,” Floyd Patterson said of The Champ in a 1966 interview. “The public demands that its champions also be popular, and sometimes popularity is achieved by keeping your mouth shut, but Clay isn’t this way.” Just months later, in April of 1967, Ali refused to be drafted into the military. “I’m not gonna help somebody get somethin’ my Negroes don’t have. If I’m gonna die, I’ll die now — right here fighting you,” he said. “You my enemy; my enemy is the white people, not the Viet-congs...You my opposer when I want freedom. You my opposer when I want justice. You my opposer when I want equality.” Equal parts poet and provocateur, Ali was everything and then some.

Harry Benson / Getty

Harry Benson / Getty

Even in defeat, which arrived so little that he became unaccustomed to it, Ali was unparalleled. He was an exclamation. A denunciation of all that chained black prosperity.

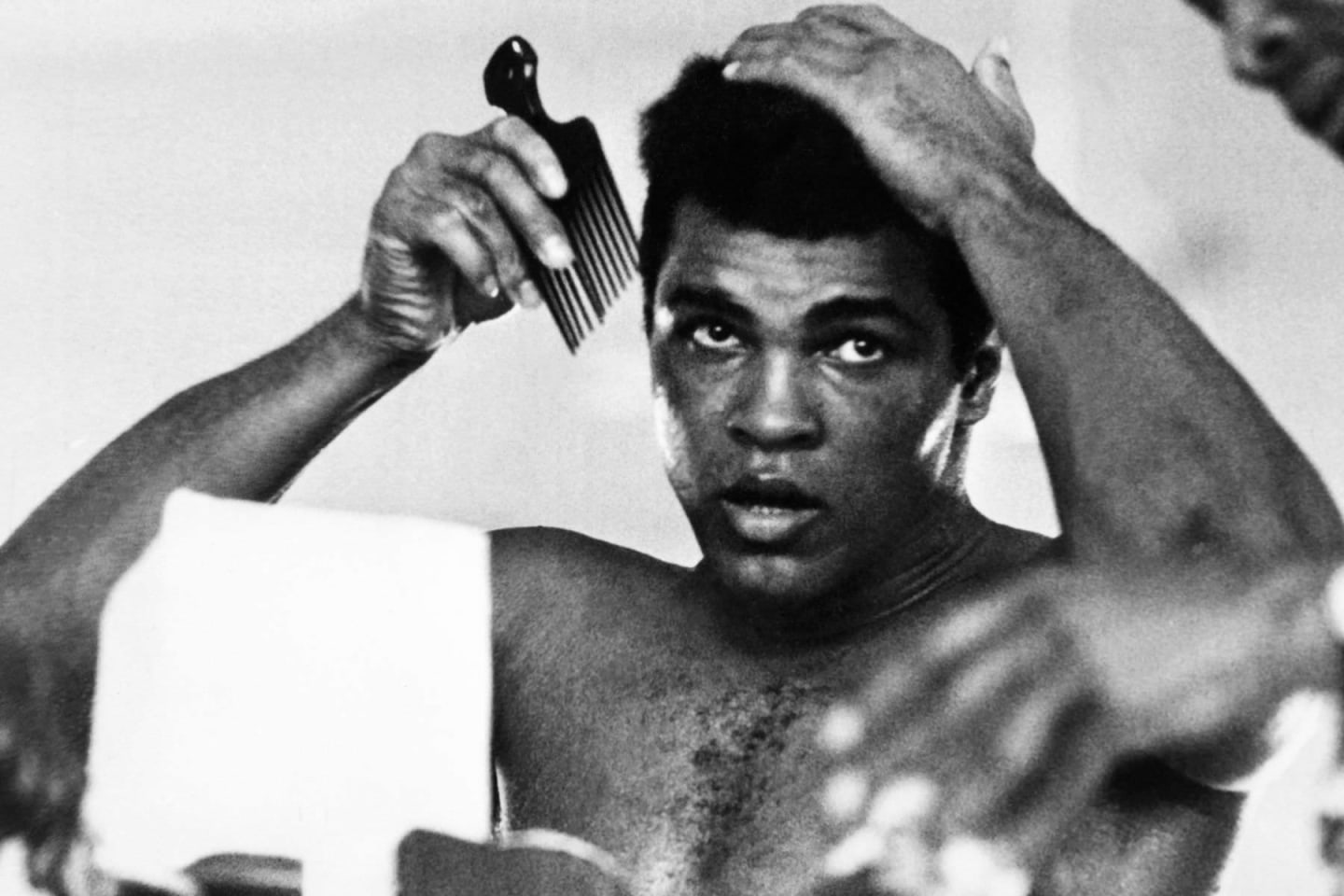

Muhammad Ali was genius in motion; a gorgeous, fantastic riot of a man. To consider his vastness is to think of beauty, and how for him, black beauty — the belief in it, the uncovering of it, the love for it, in all its splendor despite what the world said — comprised his life’s work, his blood and sweat. “I’m so pretty I can’t hardly stand to look at myself!” Ali, then just an up-and-coming showman, said to Liston in February 1964, before their first title bout. It was a motto and a way of life. In every moment captured, in every recorded match, Ali fought for the beauty of black folk to be seen. He wanted the world to appreciate the rhythms in our speech and our strut, to see our joy and our smiling faces in the wake of victory. He wanted the world, too, to feel our pains. “I love my people...they catching hell. They hungry...They getting beat up, shot, killed, just for asking for justice,” he told Esquire in 1968.

I don’t want to rip Ali of his blackness, of the reality he wore so proudly and sometimes very painfully, so I will not profess that he transcended his race, as others have done since the news of his death was announced. When Ali avowed “I’m the greatest!” it was both incitement and prophesy — deep, deep down in his Kentucky-born bones he meant every word. Ali was particularly American in the way blacks are often only allowed: loved in sport and entertainment, but mostly despised in private. He was a black man, at the nexus of spectacular fame and public hate. His very existence in the ring set out to correct the course of American history. And because he could not directly order the complexities of American history in everyday life for everyday people, he was compelled to defeat them in the ring, on television, in interviews, and wherever he could erect a podium to preach. Two years before his last ever fight, Ali revealed as much to film critic Roger Ebert, saying: “I have been so great in boxing they had to create an image like Rocky, a white image on the screen, to counteract my image in the ring. America has to have its white images, no matter where it gets them. Jesus, Wonder Woman, Tarzan and Rocky.”

Once, in conversation with Ali, Nikki Giovanni read a poem in which she remarked: “I think we are all capable of beauty, once we decide we are beautiful.” From the beginning Ali knew he was beautiful.

I came of age in the 1990s, a decade after Ali’s final match, and all of what I know about him has been discerned through grainy YouTube clips, boxing footage, documentaries, magazine profiles, and memories passed down by family members who witnessed him in real time. What remained present in all of those tellings, though, was Ali’s belief in us — in black folk. Sure, he was a world-class, prize-winning boxer who came to represent a great deal. He meant so much to so many. But his certainty in the richness and truth of his people was unmistakable. He wanted the world to know we were beautiful. He wanted us to know we were beautiful, too.

Of course, beautiful was not always something the descendants of slaves were told they could be. Beauty is awarded; it’s a trait typically given to the the best among us. Ali was not the only man of his time to wear self-respect or self-love like a badge; many blacks during the Civil Rights era wore their blackness loud and regal — Stokely Carmichael, James Baldwin, Fannie Lou Hamer, and a multitude of others. But Ali countered the reality of racial contempt by embracing black beauty in the public space on a very public stage, before millions. “I’m pretty...I shook up the world. I shook up the world. I shook up the world,” he boomed, awash in yellow light under the rafters of Miami’s Convention Hall in 1964.

Four years later, more than a decade before he would retire and more than 15 years before he would would be diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease — what he would call the greatest fight of his life — Ali chose his truth, not for the last time, and made it plain: “I could make millions if I led my people the wrong way, to something I know is wrong. So now I have to make a decision. Step into a billion dollars or step into poverty. Step into a billion dollars and denounce my people or step into poverty and teach them the truth. Damn the money. Damn the heavyweight championship. Damn the white people. Damn everything. I will die before I sell out my people.”