The concept for the video of Rick Ross’s menacing breakout hit “Hustlin’” is not subtle—it goes like this: there are two sides to Miami. The clip’s introduction starts out on Collins Ave, with generic Cuban cha-cha muzak soundtracking women in string bikinis as they walk the famously upscale South Beach strip. Then, as the swelling organs, snappy snare roll explosion and woozy, manipulated “everyday I’m huss-a-lin” chant of Ross’s single take over, he drives a white 745 Beemer past the cruise liners docked at the Port of Miami, until the camera lens suddenly switches to sepia and gives the video a sun-scorched hood griminess. Ross swaps out the super-clean BMW mentioned in the song for a souped-up Chevy and heads towards the city’s infamous Carol City neighborhood. The rest of the video takes place in the parking lots of a catchall ghetto department store called Carolmart, and a massive, windowless concrete bunker of an establishment called Club Rollexx.

It may seem like a hokey concept, but ever since the song “Hustlin’” took over airwaves and mixtapes across the country, this “two Miamis” Miami has been Ross’s real-life routine whenever he’s not working his big hit on long radio promo tours. Meet up with Ross in Carol City and he’ll probably put you in his Rolls Royce Phantom (he drives it himself) to go cruise “the Beach” for a while; meet Ross in South Beach, and after an hour or two he’s ready to switch back to Carol City. With traffic and pit stops, it can take damn near an hour to get from one to the other, so it’s not a coincidence that his favorite place to smoke a blunt seems to be behind the wheel. On one car ride towards the Beach, Ross is five sixths of the way through a strawberry Phillie, playing his new mixtape loud as fuck, when we have to stop in the cash lane at a toll booth. “The express pass is for weed smokers,” he says with frustration. “This shit is a fuckin interruption.”

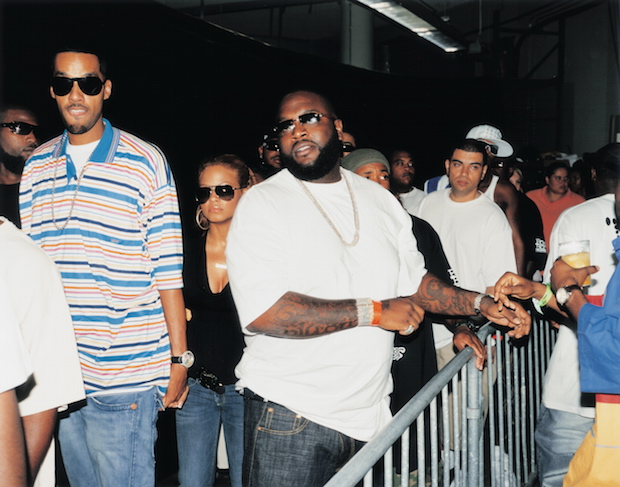

It’s Miami Springfest weekend, and although we’re headed for South Beach, Ross takes a detour to ride by Bayfront Park, where a huge radio-sponsored concert featuring Lil Wayne, Bun B, Three 6, Paul Wall, Young Jeezy, Mike Jones, Juelz Santana and everyone else who’s recently sold between 500 thousand and two million copies of an album is already getting underway. Ross has never had a licensed record for sale, but he’s been given one of the night’s prime slots for a simple reason. When we had initially met up with him earlier in the day, he was doing drops for a local Clear Channel radio station, Beat 103.5. At one point the DJ instructed him, “Now say, We’re gonna finish it out with my song ‘Hustlin’,’ the hottest record in Miami.” Ross squared up to the mic and said, “We’re gonna finish it out with my song ‘Hustlin’,’ the biggest record in the country.”

It’s still hours before Ross is due to hit the Springfest stage, but we’re over by Bayfront because he wants to show us his promotional presence and buoy it with a spontaneous drive-thru appearance for the milling crowds. Die-cut posters at the top of every light post in the area announce Rick Ross and his album Port Of Miami, Coming Soon. As we stop-and-go through traffic, Ross points at the promo posters of other artists—ripped, dirty, and hung 15 feet below his—and asks, rhetorically, “Who are you?” In addition to the huge posters, there’s also a tethered Rick Ross hot-air balloon bobbing above a parking lot, a giant inflated gorilla that announces his manager E-Class’s label with the words “Welcome to Poe Boy, Florida,” and we pull up next to an actual-factual white diesel semi truck that’s plastered with caricatures of Ross’s face. E-Class is at the wheel.

“Do you know how quickly you can spend a million dollars on this shit?” Ross asks, pointing up at another endless line of promo boards as we finally shake free from the traffic and speed over the bridge towards the Beach. “We said fuck it and bought all the machines and equipment, and we print everything ourself. Now labels see what we do, and they paying us to print they shit.” E-Class also bought Poe Boy Entertainment an industrial cherry picker so their street team can reach the spots nobody else can reach. They put everything up at 4 AM the night before a show, they get permits when necessary, and when the event is over, they go right back out and take everything down so it can be used again. E-Class even has someone guarding the inflatable gorilla for the weekend.

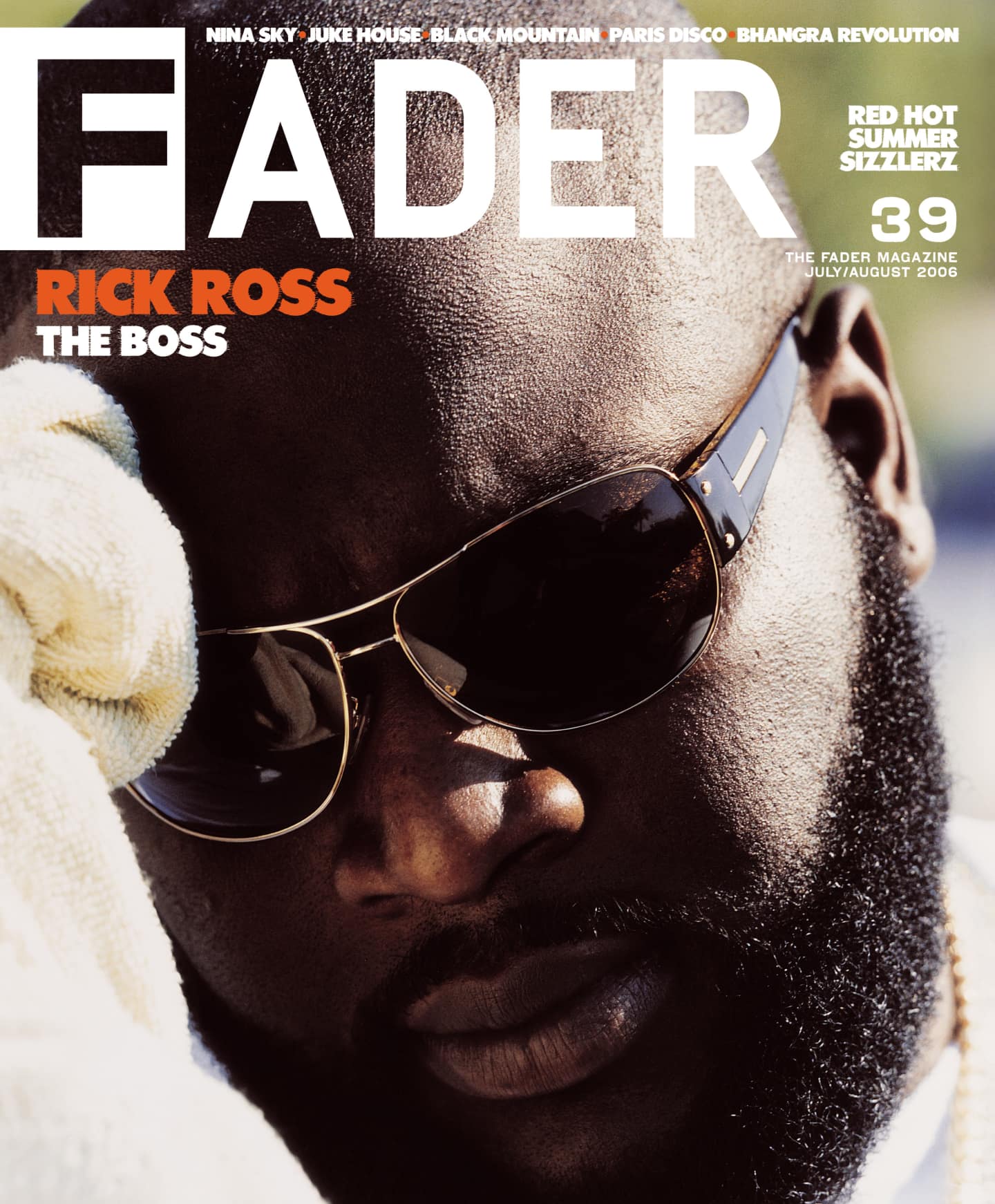

As we settle into a table at the poolside bar of an expensive South Beach hotel, Ross sniffs the air and says with a smile, “Money—I can smell it.” Rick Ross is a huge man, over six feet tall and over 300 pounds, plus the great wall of a beard and the nearly ubiquitous shades barricade him off even further. Maybe the weed has something to do with it, or it could just be because he’s lost his voice from working non-stop, but it seems that he prefers not to talk—he gives the distinct impression that he says one out of every 20 things that cross his mind. And nothing is more surprising than the rare occasions when he takes his sunglasses off—he has huge, soft, doe eyes, with eyelashes so long and perfectly curled they look fake. Add four diamond chains around his neck, a two-inch-wide diamond cuff and the holy trinity of new jeans, Nikes and a crisp T, and understand that Ross knows the impact of his presence and carries himself with the attendant swagger.

As we’re waiting for a server, Ross delivers a rare and brief monologue about supply and demand and the innate ability of dealers to find buyers and vice versa. It is unclear whether he’s talking about his former acumen as a coke dealer or his current ability to find weed, but that’s the blurred line he walks to maintain the irresistibly over-the-top Rick Ross, Dealer-Turned-Rapper persona. Ross gives the impression that he understands something about the underbelly of the decadent scene around us that’s invisible to the untrained eye. As if to illustrate the point, Poe Boy’s Vice President Gucci Pucci, who often accompanies Ross, gives a subtle half nod backwards over his shoulder to point out two black teenagers with dreadlocks who are sitting on a pair of deck chairs pulled up by the pool. “Now, what do you think they’re doing here?” he asks.

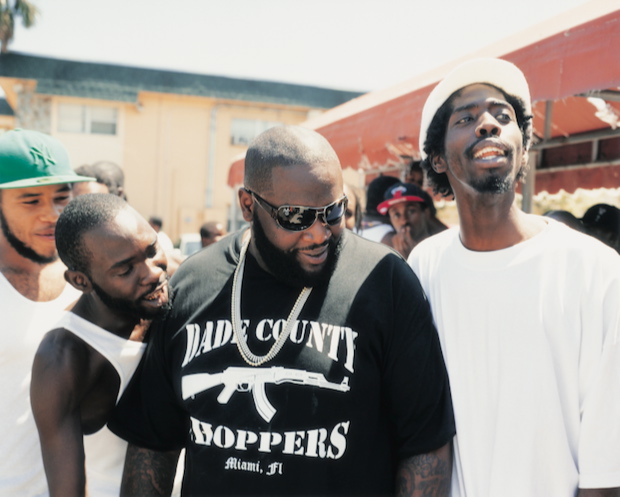

Rick Ross was born in Carol City—the other Miami. His father, who moved away when he was in fifth grade and passed away soon after he finished high school, was from Miami, and his mother moved there from Mississippi two years before he was born. Ross’s relationship to hip-hop began when he first heard Luke Skywalker records in elementary school, then he got a copy of Ice Cube’s Amerikkka’s Most Wanted in junior high and immediately connected it to what was, as he puts it, “going on inside my house.”

At Carol City High he was known as a football player and a weed smoker (he first smoked with two of his sister’s friends at age 13), but he kept his rhymes to himself. “After high school that’s when I started getting serious, trynna write a whole song, a chorus, a hook,” he says. “You know, learnin what 16 bars is because before I’d write 50 bars—that’s a verse—and have three of them with no chorus and call it a song. That’s also when I really started getting in the streets more.” While throwing himself into music—learning the craft, getting beats together, booking studio time under his original name Teflon Don—Ross began hanging out in the Carol City projects known as the Matchbox. “My momma did a great job raising us, but I wanted more,” he says. “I knew at the time that I didn’t wanna be a tough guy—I didn’t wanna be nobody I wasn’t—but I wanted to make some money. Given the surroundings I was in, I didn’t have to go somewhere and take all these big risks. All I had to do was have what they wanted and stand where I was standing at anyway.”

Although the glorified drug dealer image Ross projects in his music is outrageously and entertainingly hyperbolic, nobody doubts his credibility. Yet the street persona overshadows his long grind as an underground rapper in a city that has always been closely associated with hip-hop, but has produced relatively few stars of its own. Dre, of the ultra-successful Miami-based production duo Cool and Dre, is an up-and-coming exception to that rule, and someone who has known Ross for years. “When I first met Ross, he was ghostwriting records,” Dre says. “This was back in the day when we had a studio at Cool’s mom’s house. He just started rapping, and I was like, ‘This dude is dope.’ And he’s big, but at the same time you forget that he’s big because his swagger is so crazy. I was like, ‘Yo this dude is a superstar.’ That was in 1999.”

Ross connected with E-Class’s Poe Boy Entertainment and signed to Miami’s most successful label, Slip-N-Slide Records (home to Trick Daddy and Trina), yet he was unable to catch a significant break. He built a relationship with the biggest DJ on local radio, DJ Khaled, but over the course of three years of constantly trying to get his new records on air, he was disappointed time and time again. Then Ross brought Khaled “Hustlin’.”

Part of the genius of the song that transformed Rick Ross from an underground MC to the most sought-after new rapper in hip-hop, is that, although “Hustlin’” has a bull of a beat that might have trampled a lesser personality, Ross managed to harness it, overshadow it, turn it into an instant star-making platform for his outsized coke-slinger charisma. The world’s introduction to Rick Ross was simple enough: Who the fuck you think you fuckin with, I’m the fuckin BOSS/ Seven forty five, white on white, that’s fuckin ROSS. And it has more or less been a wrap from there—the rest of the song’s addictive couplets are just strung-together details, delivered with such outrageous style that a few of the more quotable phrases have been injected straight into the current slang: “whip it, whip it, real hard,” “M-I-Yayo,” “I caught a charge!”and more. Ross has also perfected an exaggerated version of his own slow-bellow Southern accent—he’s constantly saying “Rawssss,” and “Bawssss” out the side of his mouth, and on “Hustlin’” he transforms words like “pitching,” “snitching” and “finished” entirely: Major League—who catchin because I’m peeitchin?/ Jose Canseco just sneeitchin because he feeineeished....

Since “Hustlin’” exploded, Ross’s phone has been ringing non-stop, so much so that—after he almost brings the rafters of Bayfront Park down with his verses off Khaled’s “Holler At Me Baby,” Dre’s “Chevy Ridin High” and a multiple-rewind version of “Hustlin’,”—E-Class has cleared Ross’s schedule for a full week so he can get in the studio and actually work on his own damn album for once. With a full decade of grinding behind him, his breakthrough brought on a bidding war that Jay-Z and Def Jam ultimately won. It also brought on a landslide of requests for featured verses as legends and newly minted artists alike sought to co-opt just a little of that ultra-fresh, ultra-credible “Hustlin’” street magic. In the meantime, Ross and Poe Boy have kept new mixtapes in the streets, but many of the songs are misleading, as Ross phones in “cars and coke, coke and cars” verses that sound like cumbersome freestyles. So instead, it’s on some of those guest features—songs with Paul Wall, Lil Wayne, Pimp C, Too $hort, Birdman, NORE, Trina, Trick Daddy, Daz and more—that there are hints of what to expect when Port Of Miami drops.

Dre, for one, has obviously been in the studio with many talented MCs, but the producer swears Ross will prove to be one of the three best rappers alive. “In my opinion, in ’99, 2000, 2001, he was on Jay-Z’s level at that time,” Dre says. “But he was unknown and putting everything on the plate at one time, and it was too much for motherfuckers to handle. So he was like, ‘I’m gonna dumb shit down for you motherfuckers,’ and on ‘Hustlin’,’ he dumbed it down.” Dre then goes on to quote the opening lines of a song called “Blow” that Ross has recorded for Port Of Miami: A big blunt full of kush/ A bomb of heron tucked in the bush/ I don’t give a fuck, I’ll send a nigga like Bush/ You sitting on top I give your ass a slight push/ Motherfucker how the bottom feel?/ I had a lot of scrill way before I got a deal/ I used to wet yay way before I met Jay/ Like chess/ For your boy, that day was checkmate....

Ross might have claimed in the rhyme that his deal with Def Jam was “checkmate,” but that was merely an early round victory—an amateur league championship title that came with an invitation to the pros. In other words, there is still a lot of untapped opportunity in Ross’s future. The night we arrived in Miami, some 20 hours before we met Ross for the victory lap tour around Bayfront Park, we were with Ross’s publicist from Def Jam, Gabriel Tesoriero. He showed us a transmission on his Blackberry from earlier in the day with Jay-Z, in which he reported to his boss, In Miami with Ross, he picked me up from the airport in the white Phantom. Jay responded, Tell Ross he’s finger-fuckin this money. If he delivers me a smash, I’ll send him to the moon. He passed the message on to Ross, then sent Jay the response, which read, Ross says: “Tell Jay I’m puttin on my space suit now. How long’s the flight?”