What Happened To DIIV?

As his band prepares for a comeback, Zachary Cole Smith returns to the city where he almost ruined his life.

Four years before DIIV played its first show, Zachary Cole Smith moved into an apartment with a girl he barely knew. They shared a bedroom in Brownsville, a mostly un-gentrified Brooklyn neighborhood that’s generally regarded as one of the borough’s more dangerous areas. When their relationship crumbled a few months into the lease, Smith hopped in his Ford pickup truck and started driving. “I didn’t even know where I was going,” he tells me. “As soon as I went through the Holland Tunnel, I was like, Wow, I’m gone.”

Smith crossed America slowly, crashing with friends in cities where he had them and sleeping underneath his truck bed where he didn’t. After a misguided attempt to visit his ex-girlfriend in San Diego, he had the idea of reconnecting with his long-estranged father, who was working in a music studio in San Francisco at the time. “All of a sudden, I was living in his house,” Smith says. “I asked him, ‘Hey, is there a job in your studio I could do?’ He was like, ‘Yeah, you can paint it.’ After a week, I was like, ‘Fuck this.’” Desperate for cash, Smith found a girl in San Francisco willing to pay $1000 if he drove her things—packed suitcases, a moped, and a “fuckload” of weed—to the East Coast. So, roughly six months after first setting out, Smith loaded up his car and headed back to where he started. “I drove from San Francisco to New York in five days,” he remembers. “I just wanted to get the fuck home.”

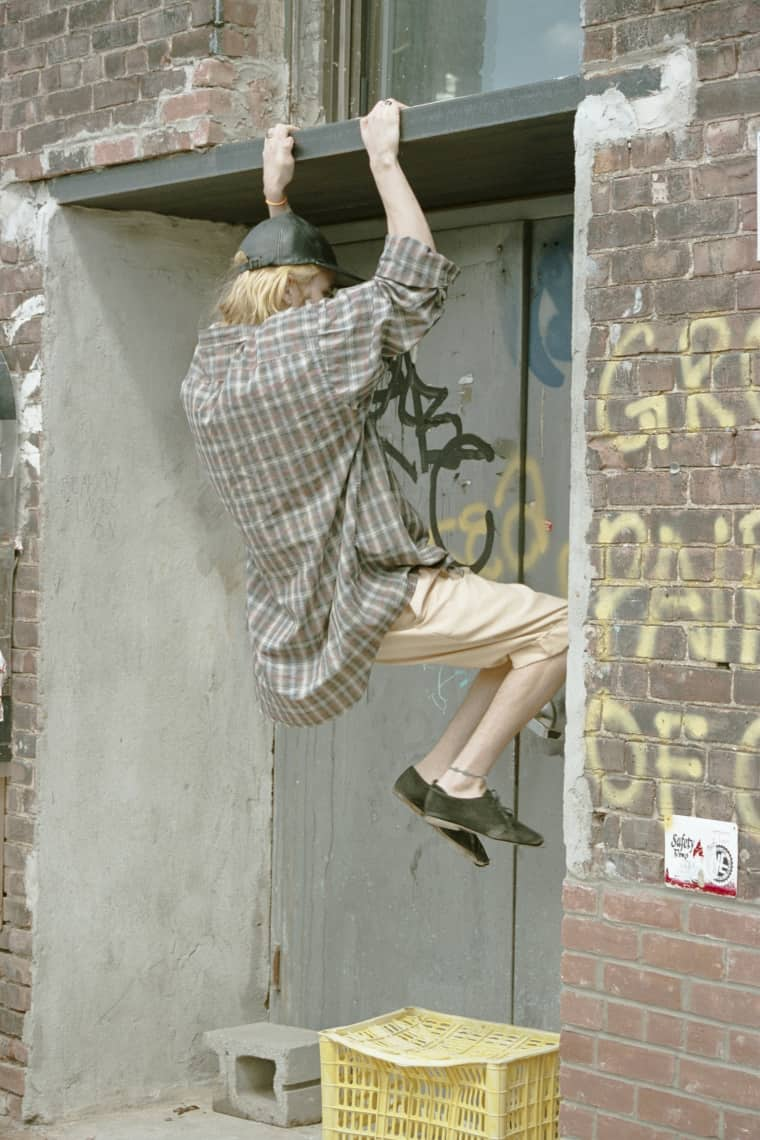

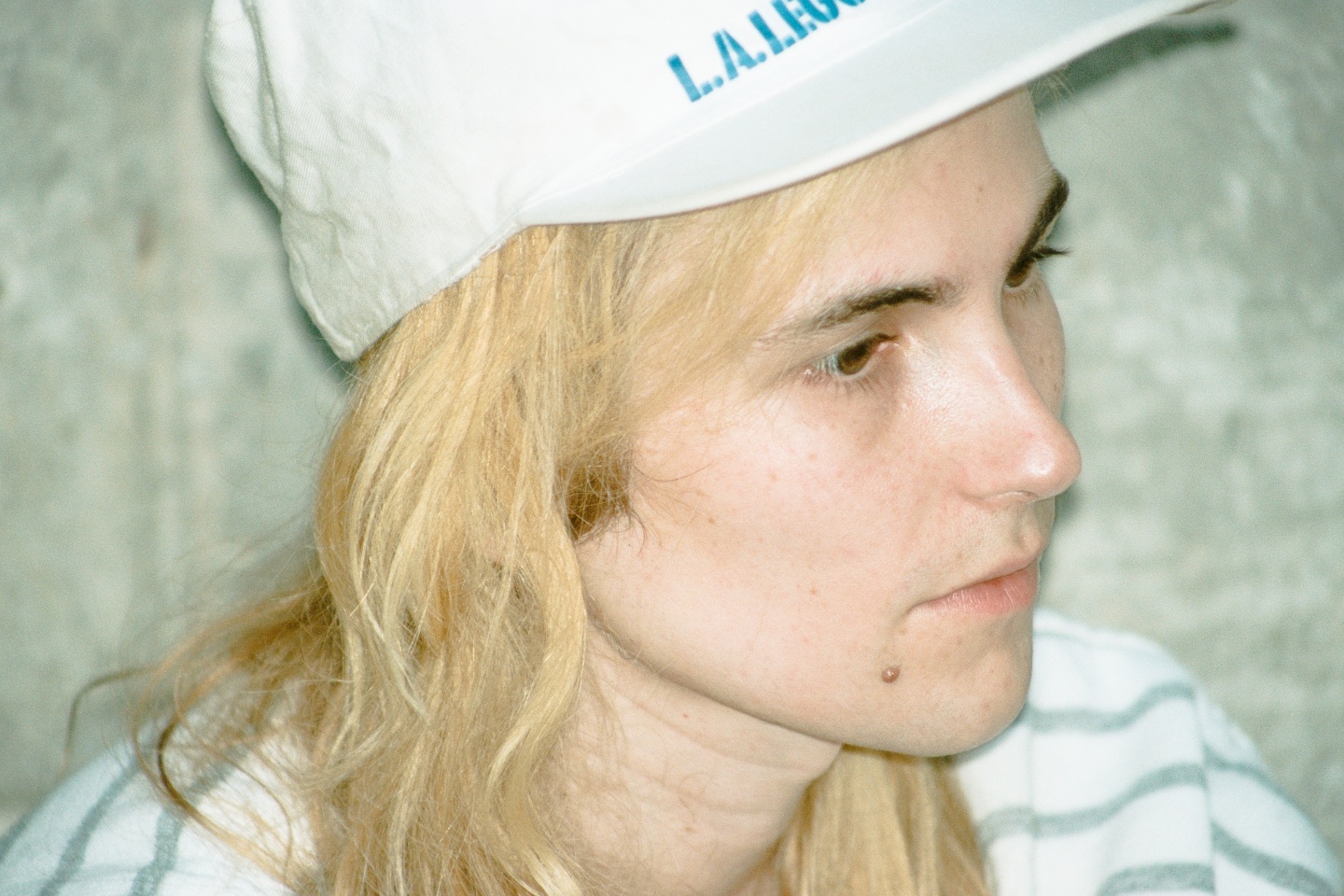

Smith was born in New York, and no matter where on earth his urges take him, the city always lures him back. We’re sitting at a window table inside one of Greenpoint’s traditional Polish bakeries, sipping pink sodas. It’s nearly sundown, and the modest eatery feels peaceful in the soft light of dusk. Looking across the table at Smith, who’s gone by “Cole” since birth, you’d never know that we’re only a couple days from full-blown Brooklyn summer: the small-framed 30-year-old has layered two drastically oversized shirts—one tee, one tunic—atop some ragged beige trousers with gaping knee holes, his shoulder-length yellow hair stuffed under a tan Polo cap. It’s more or less his signature look, midway between a Seattle grunge rocker and a scrawny schoolboy playing dress up in his father’s clothes.

Half a block away, a freelance audio engineer named Kurt Feldman is working on Is the Is Are, the long-time-coming sophomore release by Smith’s rock band DIIV, which formed in 2011. Almost as if to make up for lost time, the new album will spread 18 songs over two discs. Smith says he’s shooting for a 75-minute runtime, just like his favorite double LPs: Fleetwood Mac’s Tusk and Can’s Tago Mago. Since it’s due to be mastered in two weeks, Feldman has been tasked with some last-minute damage control after the primary mixing sessions left some uncomfortably loud tape hiss in the mix.

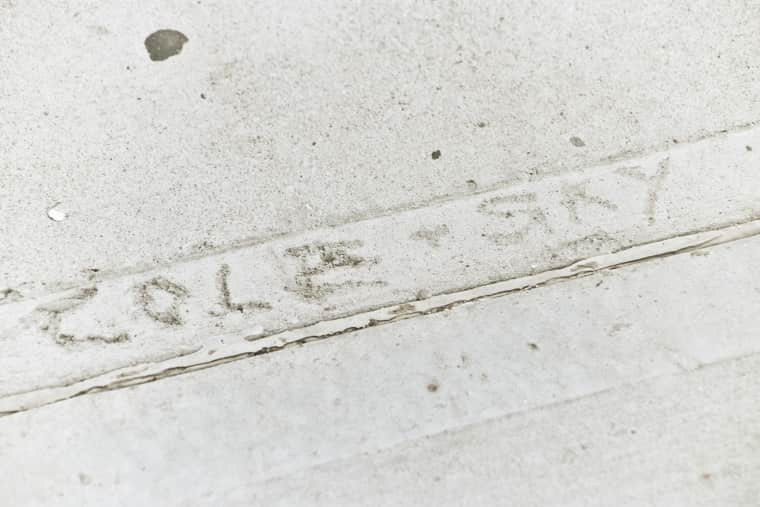

The album isn’t the only deadline looming. An occasional model for Saint Laurent, Smith is headed to Paris in less than a week to walk the runway at the legendary fashion brand’s latest menswear show. Before that, he’s flying to California to visit his beloved girlfriend of two-and-a-half years, the singer, model, and actress Sky Ferreira, who’s currently hard at work on her own new record, which Smith says is “just fucking mind-blowing.” The couple is also in the early stages of finding a new apartment in New York. On top of it all, tomorrow he’s getting kicked out of the two-bedroom home-away-from-home he’s been renting for almost two years—but rarely visits—in Catskill, a sleepy town a couple hours north of New York.

It might be for the best, though, since Catskill seems to be a reminder of stuff in Smith’s life that he’d rather forget. On September 13th, 2013—the night before DIIV was scheduled to perform at Basilica Soundscape, a three-day music festival held inside a renovated 19th century factory in Hudson, New York—Smith’s unregistered Ford pickup truck was pulled over in the nearby town of Saugerties. Smith had heroin on him, and Ferreira reportedly had ecstasy—although her charges were later dropped entirely. After Ferreira made bail, she spent several traumatic hours waiting for Smith, completely alone inside the sparsely furnished one-floor Catskill house without food, heat, or internet. After that weekend, she never wanted to go back.

Watching the couple’s hollow-eyed mugshots make the rounds on nearly every major music site was taxing for Smith, but he seems to feel the worst about landing his then-21-year-old girlfriend behind bars; he says Ferreira didn’t even know he was still using at the time. “Everyone thought she was a junkie,” he remembers of the media shitstorm that followed.

The arrest isn’t the only hiccup that has haunted DIIV in the three years since Oshin, the critically acclaimed debut album that perched the band precariously on the brink of big-time success. According to Smith, DIIV’s original drummer Colby Hewitt is no longer in the band as of this spring, due to an alleged struggle with multiple drug addictions, and bassist Devin Ruben Perez spent the end of 2014 shrouded in controversy after making a host of gross comments on 4Chan. Is the Is Are could be a real moment of redemption for Smith, the frontman of a truly polarizing band that’s spent the past few years making headlines for everything other than its music. Smith, for his part, says he’s trying his hardest to stay clean. “I feel like I owe the world a good record,” he tells me. “I was blessed enough to get this far; it would be such a shame to sputter out now.”

Devin Ruben Perez and Andrew Bailey

Devin Ruben Perez and Andrew Bailey

Smith’s pre-DIIV past has some dark patches too. Though he was born in the city, he grew up in suburban Connecticut with his mom, a one-time Vogue editor he describes as “one of his very best friends,” and his younger sister. His father, a musician also named Zachary, moved the family to the suburbs not long before he up and left for good; Smith was four, and his sister was just a baby. “I don’t care what actually happened at this point,” Smith says, “because no matter what, I don’t think he did much to remedy it. I saw it as like, ‘Oh, I have a dad one minute, and the next I’m like, Where is my dad? What happened?’”

When Smith was a freshman in high school, he and a friend went out looking for smokes and ended up smashing a bunch of truck windows with rocks in the parking lot of a Wal-Mart. Both boys were arrested, and Smith was expelled from school. “I was completely running wild,” he remembers, noting that it was during this period that he began experimenting with drugs and alcohol. “I was the first kid to show up [to school] with weed,” he recalls. A couple years later, one of his close friends from this stretch would die from an overdose. When he tells me this, it’s like he’s remembering it for the first time in a long time. “I feel like in some bizarre world, that could have been me,” he says.

After his stepdad borrowed money to enroll him in private school, an unruly-as-ever Smith pinballed from prep school to prep school, first meeting DIIV guitarist Andrew Bailey at one of them. “Cole looked like your stereotypical nerd,” Bailey will tell me later, recalling one of their earliest interactions. “He had thick-framed glasses. He dressed kind of like Rivers Cuomo meets a British punk. And he looked really young. This one kid started picking on him, and he was just like, ‘Shut the fuck up you motherfucking cocksucker! I’m going to go smoke cigarettes.’ Everyone’s jaw dropped, like, ‘Woah, what is that person?” It’s a story that hints at the loose-cannon quality that would make Smith such a magnetic frontman over a decade later.

After high school, Smith spent a year and change at Hampshire, an experimentally minded liberal arts college in Western Massachusetts. A couple days after finding out he wasn’t going to be invited back for his sophomore spring semester, Smith met a girl named Jenny at a New Year’s Eve party in New York. By January 1st, 2007, he was living in her Brownsville bedroom.

Not long after his impulsive cross-country trek, Smith landed a job at Angelica Kitchen, a cozy East Village restaurant that’s been serving tasty vegan food to artists and hippies since the ’70s. Through work, he started connecting with New York’s thriving underground music scene: if hungry musicians came in looking for free food, Smith would share what he could. While he’d played guitar since he was a small child, even starting a half-assed band with Bailey and another friend in high school, he says he’d always considered it more of a hobby than a calling: “It was just something I knew how to do.” It wasn’t until 2010, after a couple years playing in the local psych rock band Soft Black and the well-liked jangle-pop outfit Beach Fossils, that Smith, then 26, decided to start writing his own rock songs.

At first, Smith says his biggest goal was getting signed to Beach Fossils’ record label, Captured Tracks, a tastemaking Brooklyn indie. After recording a couple tracks himself, Smith enlisted his old friend Bailey, now a tall and lanky guitarist; former Smith Westerns drummer Colby Hewitt; and bassist Devin Ruben Perez, a long-haired, chicken-legged, once-homeless New York scenester who’d never played in a band before. They were called Dive back then, before Smith changed the spelling “out of respect” for an early ’90s industrial band from Belgium. In October of 2011, Smith signed a deal with Captured Tracks. “Cole had a plan, and we were part of the plan,” label founder Mike Sniper tells me over the phone.

By that time, DIIV had already started gigging relentlessly all over New York, sometimes playing two shows on the same night. Their dark, drugged-up songs had a lot in common with the internet-generation slacker rock that had been flooding the city’s underground for the past few years, an era marked by cassette-quality production, time-warped guitar tones, and hazy vocals. But something about DIIV’s textured songcraft—the tangled-up riffs, the motorik grooves, and the mind-numbing repetition—made that lo-fi rock formula seem sorta new again. Their music felt like sped-up shoegaze for late-night weirdos, and the band performed it with a gripping, nothing-else-matters punk energy. “Part of it was who we were, who we knew, and what we looked like,” Smith remembers of their early reception, which may have been at least partly influenced by their too-cool, ragamuffin charms. “But it also had to do with the songs, and how much we were willing to play.”

“I feel like I owe the world a good record. I was blessed enough to get this far; it would be such a shame to sputter out now.”

For a while, it was almost like DIIV was the unofficial house band of 285 Kent, a wide-open waterfront warehouse known for its all-over-the-place lineups and unhinged parties that were, according to Smith, “legendary to anybody who was ever there.” The music video for Oshin single “Doused,” a song about his complicated relationship with his father—It stops and starts/ A gesture here and there...you blew it/ Now you’ve gone too far—features the bandleader full-on sprinting through the moonlit streets of Brooklyn, hurrying to join the rest of the band thrashing around on the venue’s stage. Today, 285’s unmarked door has been shut for more than a year, and its neighboring DIY havens, Glasslands and Death By Audio, are closed too. (The building in which all three were located is now being rented by Vice.)

By the time Oshin came out, in June of 2012, DIIV had a booking agent and didn’t really need to play as many shows around town. With all the hype surrounding his project, Smith says he started feeling alienated from his peers in the scene. “I walked into 285 Kent the day [the record] came out, and all these people are like, ‘Hey man, congrats on Pitchfork. Best New Music!’ I felt like they thought I was better than them, or that they thought I had a big head. Like, ‘Why you?’ I never really felt like a true part of [the community] after that.” Today, the version of Brooklyn that DIIV outgrew doesn’t really exist anymore—at least not in Williamsburg. A few days after our first meeting, when I ask Smith to suggest a place to grab a drink, he arbitrarily chooses a yuppie-friendly bar called Black Bear, not realizing that it was constructed on the site of Public Assembly, a venue DIIV used to play before it closed, near the end of 2013. He may have picked it because it was a quick walk from his and Ferreira’s apartment. More than likely, though, he just doesn’t know where to go anymore.

The next morning, on a sterile North Williamsburg block about half a mile from the old 285 Kent, Smith answers the door in only a beach towel. He dashes around the two-floor apartment with the energy of a kid before a field trip, his wet hair pulled into a messy high ponytail. Since he and Ferreira are moving soon, the place is a total wreck: the couch is hidden beneath piles of seemingly clean clothes, and there’s an empty, sad-looking fish tank that dried up after Smith left it in the care of a flaky housesitter. The lower level is just as cluttered, with racks upon racks of Ferreira’s chic clothing, plus a bare twin mattress and a flatscreen TV that doesn’t work. “Sky would kill me if she knew I let you in here,” Smith says.

After Bailey arrives, we cross the street to the parking lot where the DIIV van has been sitting dormant since the end of last year, when the band put touring on hold to concentrate on writing and recording the new LP. Smith says he had to pay $1700 in overdue fees to even be able to take it out. It’s a little after 10AM, and the three of us are making the two-hour drive to Catskill to collect the last of Smith’s stuff from his house up there. While waiting for the van’s tires to fill up with air, Smith and Bailey play tic-tac-toe on the dust-covered window.

On the road, the pair chat about writing Is the Is Are in January and February of this year, when Smith rented a warehouse and flew the whole band to L.A. to help him expand on the demos he had written alone. They’re candid about the difficulties of collaborating with recently departed drummer Hewitt, who Smith says is a “hardcore fucking drug addict” and had trouble learning the new songs. (Via email, Hewitt denied drug use as the reason for his departure, citing instead a lack of steady income from the band and creative frustrations. “I quit because I never really liked the music that much,” he explained.) On DIIV’s recent European tour, Oshin session drummer Ben Newman filled in. It’s bright out, and Bailey is driving carefully on a winding, two-lane country highway with a jagged rock face running along its right shoulder. “Colby just needs to figure his shit out,” Smith says from the passenger seat. “When I had my shit, I figured it out,” Bailey adds, hinting at his own trip to a Georgia rehab facility, in 2013, after trying to quit drinking cold turkey sent him into a life-threatening withdrawal. “This road freaks me out,” Smith says suddenly. “It’s, like, falling apart.”

“There’s a lot of people around me who were doing really badly, and there were a lot of people around me doing well. And I knew which one I wanted to be.”

If you ask, Smith will tell you about getting high. He’ll tell you that when tripping in groups, he prefers to drop the LSD a few minutes before everyone else so that he can be “the leader,” and he’ll tell you about a time he spent staring mindlessly at a wall for 12 hours straight after trying meth in Los Angeles. He’ll relay nerve-racking anecdotes about shooting up cocaine and cushioning the comedown with heroin, a sensation he likens to getting struck by a freight train and crash-landing in a pillow factory. “There’s an expression I always think about,” he says: “A smart man learns from his own mistakes; a wise man learns from others’ mistakes. I’ve been able to apply that to my life in a lot of ways, but when it comes to drugs, I can’t be told, ‘Don’t do it.’ I have to try everything for myself. I couldn’t live my life knowing that there was this insane experience that I was missing out on.” When he started DIIV, Smith says he found himself surrounded by a lot of people using drugs, including smack. “It was, like, everyone,” he says of the particular clique of New York creative types he’d fallen into. Soon enough, he was using too.

By 2013, Smith’s growing addiction to heroin started to become a serious problem. At the peak of DIIV’s popularity, a strung-out Smith couldn’t give fans what they wanted most: new music. “When I was getting fucked up all the time, I wrote literally zero songs,” Smith remembers. He tried to pull it together, but even a single day without heroin can hurl an addict into a head-spinning, stomach-turning dope sickness. In the summer of 2013, an entire recording session with ex-Girls bassist and producer Chet “JR” White was scrapped. “Quitting gets put off,” Smith says, “because there’s never a good time to feel like fucking hell.”

After the arrest upstate, Smith was formally charged with a criminal misdemeanor for drug possession. In January of 2014, he left New York for an upscale detox facility in southern Connecticut that once treated the late Philip Seymour Hoffman. The court-ordered detox was brutal; Smith says the highest available dose of Methadone—a synthetic opiate given to help ease the pain of withdrawal—paled in comparison to the amount of smack he had been injecting every day. “I think the longest opiate person they ever had stayed for seven days,” Smith says. “I was there for eleven.” To get through it, he re-read journalist Michael Azerrad’s Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana, a nonfiction book originally published a year before Kurt Cobain’s death. “It made me feel like I was back on the road with my band,” Smith says. “It made me feel like there was a world out there.” After he was discharged, he says the possibility of losing Ferreira did more to keep him straight than any recovery program. “Sky was extremely adamant that I couldn’t be using drugs and be in a relationship with her at the same time,” Smith says. “Given that choice, it’s pretty fucking obvious which direction to go in.”

Smith tells me he’s clean now, or heroin-free at least (on more than one occasion, we drink together). It’s obvious he’s excited about his sprawling new double-LP, animatedly introducing each track as he plays it in the van on the way to Catskill: “This is my favorite song!” he says. “No, this one!” He only sings along once, when we listen to a moody number featuring Ferreira speak-singing some abstract poetry. Musically, Is the Is Are is both a continuation of Oshin’s songcraft and an introduction to a sharper and more labored-over DIIV sound. Some new tracks sound angry—like “Dust,” a seismic standout that has been in the band’s live set for almost two years. And some sound pensive, such as a pretty song Smith’s been calling “Healthy Moon,” which opens with the lazily sung lyric: How can I describe this fading dream? It’s a simple sentiment, but one that seems to precisely explain the half-cognitive euphoria DIIV’s music captures, a fearless high that’s always on the verge of slipping away.

It doesn’t take long to work out that a lot of the songs are about wrestling with addiction: on one, Smith sings the Alcoholic Anonymous catchphrase, It works if you work it, and another goes, I was high but now I feel low. On Oshin, the vocalizations were muddled in the mix, just another gear in Smith’s delirium-inducing machine. “This time,” he says, “I really wanted people to be able to understand the words and connect with them.” These songs are more observational and more confessional, influenced by his personal demons and those stalking the people closest to him. “There’s a lot of people around me who were doing really badly, and there were a lot of people around me doing well,” Smith says. “And I knew which one I wanted to be.”

“I hate this fucking place,” Smith says, jostling the knob on the Catskill house’s gray door. We’re standing on stepping stones in the house’s overgrown garden, which you get to by crossing an actual white picket fence and walking down a lumpy green hill, one street over from the town’s storybook Main Street. When we finally get inside, the first thing that catches my eye is an artist badge from the ill-fated 2013 Basilica festival, resting on an ugly brown rug. Somehow, DIIV wound up performing there the day after Smith’s arrest, when Basilica founder and legendary Hole bassist Melissa Auf der Maur bailed him out of jail.

There isn’t much stuff left to pack up, though almost everything Smith uncovers seems to have some deep-seated sentimental value. Looking through the crates of books, he singles out an odd tome called Shaman that he and Perez found on the street in Brooklyn years ago. Its pages contain some of the band’s more recognizable imagery, including the ancient stone carvings Smith screen-printed onto some CD-Rs he burned for early demos of “Sometime” and “Corvalis.” During a break from loading the van, he gets a text saying that Saint Laurent is looking for last-minute male models to walk in the upcoming show. Bailey strips down to his shorts and pouts against the off-white wall while Smith snaps a few iPhone pics to send to casting.

Some of Smith’s most prized possessions are also still tucked away in the house, including two guitars. One is an electric that his father gave to him at birth; it’s dark blue and has little cowboy-themed drawings on it, supposedly made from children’s pajamas found in a ghost town. The second is a beat-up acoustic that used to belong to Elliott Smith, the singer-songwriter who committed suicide at the age of 34. Ferreira got it from composer Jon Brion—a friend of Elliott’s who collaborated with Ferreira on her 2012 EP, Ghost—and gifted it to Smith on their first Valentine’s Day together. When he finds it, he pulls it out of the case, strums a few clumsy chords, and starts to play “Alameda,” a sad song that Elliott Smith released in 1997: Nobody broke your heart/ You broke your own cause you can’t finish what you start, he sings. Nobody broke your heart.

Elliott Smith is just one of several doomed rock stars the DIIV frontman is obsessed with. He’s a big fan of garage punk icon Jay Reatard, who died in his sleep from a mixture of cocaine and alcohol, and he’s unabashed about his love for Johnny Thunders, the legendary New York punk guitarist whose seemingly drug-related death at age 39 remains a mystery to this day. And, of course, there’s Kurt Cobain, whose name comes up often during our time together, though Smith just calls him “Kurt.” In the car earlier, we talked about Montage of Heck, the recently released documentary that stitches together rare home-movie footage of the Nirvana frontman with rotoscope-animated reenactments of his early life. Smith watched it with his mother, who he says felt uncomfortable because she had trouble separating the platinum-blond boy on screen from her own son. In the homemade music video Smith directed for Ferreira’s 2013 song “Omanko,” there’s a shot of the couple in their bathroom mirror. Smith’s got the camcorder in one hand, and he leans down to give Ferreira a soft kiss on her face. It’s a romantic image but also an eerie one, like footage waiting to be unearthed by a documentary crew a couple decades into the future.

Smith seems to feel a kinship with this contingent of gone-too-soon songwriters. But at this particular moment in time, it doesn’t really seem like he’s looking for his own tragic ending—not now, anyway. There’s a beautiful new album on the way and too much to lose, including the unwavering support of Ferreira. “I’ve put her through a lot,” Smith says of his girlfriend. “She dealt with all of it and continued to love me.” It’s hard to know if the long-delayed Is the Is Are will be a success—and whether a band like DIIV can ever fully bounce back from all the blog-world controversies, addictions, and interpersonal struggles that have riddled its upward trajectory from the start. But though nothing is certain, Smith isn’t ready to give up just yet, and it’s time once again to go home to New York.

Before we leave Catskill, Smith stops at a tiny store on Main Street. “I got you a present,” he says when he emerges, tossing me a strawberry-flavored Ring Pop, and keeping another for himself. Bailey carefully steers the van onto the road, dodging a few slow-moving townies ambling around on foot. “All these upstate towns are totally stuck in time,” Bailey says as we start the drive back home. For a couple seconds, we can see the little house’s red bricks through the trees. Smith puts his slender hand out the open window, the spit-covered candy jewel on his finger glistening in the day’s last light. “Bon voyage, baby,” he says, waving to no one.