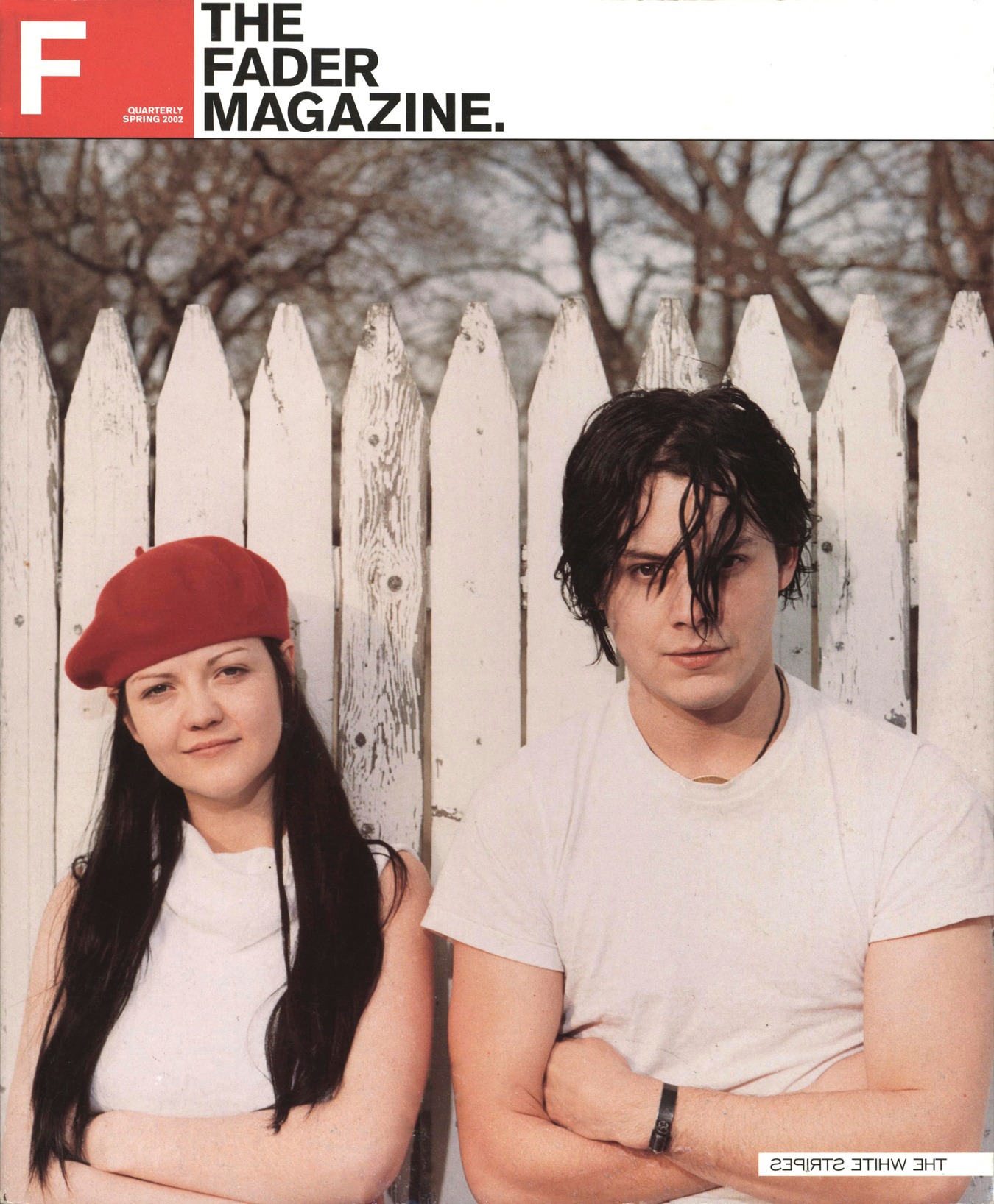

This 2002 White Stripes Cover Story Captures Rock’s Obsession With Authenticity

Online for the first time, this profile from The FADER’s 11th issue finds the Detroit blues-rock duo on the brink of super-stardom.

Back in 2002, The FADER's then editor-at-large Knox Robinson spent time with the White Stripes in Detroit for The FADER's 11th issue—and the duo's first ever cover story.

“This looks just like Buffalo,” I said from the back seat as we rode around Detroit. Meg sat shotgun and didn’t say much. “Yeah, we were just talking to Vincent Gallo and he said the same thing,” said Jack, driving their tour van, which had a remarkable edge of baked-in cigarette smoke that was oddly comforting in its familiarity.

It’s true, although the Motor City is sort of a bigger, better version of the Nickel City. Both towns were proud, brawny, intensely segregated mid-century Midwestern American cities that sagged under their own weight as the Steel Belt turned into the Rust Belt and their meat and potato-fed hearts gave out like pyoom. Look at Vincent Gallo and Rick James and Timothy McVeigh and it seems the only way to get out of cities like Buffalo is to make a career out of being from such a place, the way some people make a career out of being black or lesbian or both: you swallow the city whole and turn your freakish self inside out to see what the world makes of your guts. That, or you pretend you were never from there in the first place.

So what’s left there in the tremendous American expanse that begins in Newark and stretches to Bakersfield? What’s there in that collection of small cities and big towns after the brain drain to the coasts–to the glittery cities like N.Y.C. and Philly and L.A. and S.F., or maybe even down south to jobs in Atlanta, North Carolina, Florida or Texas? Not much, just your unhappy parents, maybe not even all of your childhood friends, just one or two of them and the old brick high school, lonely, the high school and…professional sports teams, you’d say, if you had to guess. That is, until you go to Detroit to meet Jack White, a wan, easygoing, huge-in-Europe rock star that shares his last name with his partner Meg and their band, the White Stripes. Because Detroit, at least, is still making music. It has underground techno, ghettotech and Eminem too, but there’s also an exploding garage rock scene in the city, and the White Stripes have been taken up as its media darlings.

“I think when you’re in Detroit, there’s no hope and you got nothing to lose anyways, because no one cares about the bands from here.”—Jack White

“Out on tour you really don’t seem to find places where there’s 15 amazing bands in town that you’ve heard of, but it seems like there’s 20 or 25 really interesting music groups in Detroit,” says Jack, rattling off the names of songwriter Brendan Benson, Jason Stollsteimer from the Von Bondies, and bands like the Detroit Cobras, the Waxwings and the Dirt Bombs. “It's a separation from New York and L.A.; [in Detroit] people are automatically connected to a source. They don’t have a connection to a record label. Like, if you start a band in L.A. you probably have a friend who works at a record label or a friend who works at getting songs into films or something. Or at least, if you start a band you’re looking for that immediately—because you’re in L.A. I think when you’re in Detroit, there’s no hope and you got nothing to lose anyways, because no one cares about the bands from here.”

Meg laughs and says quietly, “There’s really not much else to do.” “And no one would ever move here,” Jack continues. “It just wouldn’t happen. So the music immediately becomes that much more honest because there’s no ultimate goal of getting successful and famous. I think for a lot of rock bands in Detroit it’s the last thing on their minds even if it’s offered to them. I’ve heard people say, ‘Why would we want to be big? Why would we want to be successful? So it’s great.”

But the White Stripes are big, and famous in that tired-ass latter half of the 20th century way. Famous enough to have a reported $1,000,000 dangled in their faces to appear in a massive celebrity-driven Gap ad campaign—a payday they turned down after Jack had already sang on their third album, last year’s White Blood Cells: Well you’re in your little room/ and you’re working on something good/ but if it’s really good/ you’re gonna need a bigger room/ and when you’re in the bigger room/ you might not know what to do/ you might have to think of how you got started/ sitting in your little room…

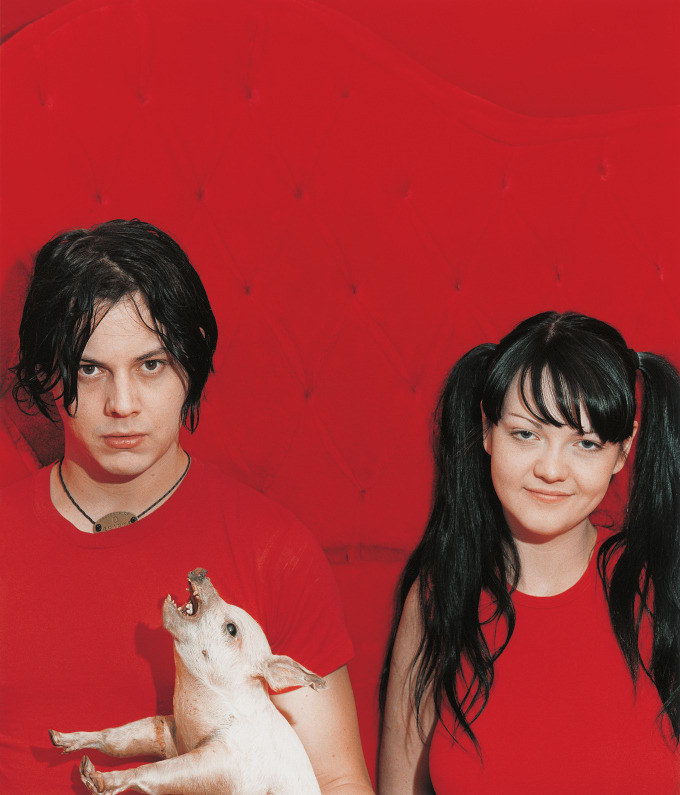

Why would they want to be successful? You can’t even ask that question in America, at least not in the new America of the New Economy and the Internet and necromantic politics and weekly record sales updates and outposts of mall culture around the world. Perhaps this is why the idea that the White Stripes might not want to blow up and go pop hasn’t really been the dominant narrative flying off the rock and roll desk over at New America Media, Marketing and Promotion, Inc. It’s probably more a function of capitalism than a simplistic matter of race, but journalists are patented suckers for white people digging into their own souls through music forms of black American origin, like the blues, jazz, rock and roll, and hip-hop. This makes for both good copy and good business sense: writers and editors love that shit, because they love to build ’em up so they can tear ‘em down—maybe because there’s nothing more dangerous to the collective than a man or woman who simply doesn’t give a fuck and takes chances. who tries to reach out and break to the other side, whatever that side may be. (“I like putting myself in other people’s shoes,” says Jack.) Here are the White Stripes, the standard brief goes, a guitar/drums duo from Detroit who say they are brother and sister and has released three noisy albums of blues-based garage rock with touches of Zeppelin and the occasional Bob Dylan or Marlene Dietrich cover. They always wear red and white. The guy is really pale and scrawls the name of obscure bluesman like Blind Willie McTell on a white T-shirt, and get this: the girl bangs the drums with a deliberate kid-like thrashing!

“We never set out to say, ‘Okay, we’re gonna be a garage rock band and that’s it—we’re gonna use the same three chords over and over again. We’re gonna make six albums and then we’re gonna stop.’ We never said that.”—Jack White

“There’s different things we love: we love country music, we love the blues, we love rock and roll, we pretty much love anything American, from the South. So we have all these different influences,” explains Jack. And so naturally because the White Stripes tried and actually succeeded at an honest visceral music that smells like cigarettes, tastes like old motor oil and hits like an alcoholic girlfriend, they have provoked the usual media hateration. Time’s Benjamin Nugent went all out, putting his J-school diploma on the line and dong a bit of tidy investigative work. “In 1996, John (Jack) Gillis and Megan (Meg) White, got married, and Jack took Meg’s last name,” reported Nugent diligently. “Jack says he grew up with ten older siblings in the southwest Detroit house he currently shares with roommates, and this is rumored to be true. Meg, he claims, grew up in the suburb of Grosse Pointe… Last year they divorced, but the band remained intact…” The British press has mainly ignored this. They’re pissing their pants because the White Stripes are the best new big thing since, well, the Strokes.

Of course, one country’s dampened knickers are another nation’s legacy of blacks and blues (or something like that), and that’s not a new story either. White people have always been obsessed with the blues, at least since John and Alan Lomax made their famous Southern field recordings (the ones Moby sampled for Play) a couple of decades before an adolescent Mick Jagger sent away for sides from Chess Records in Chicago. A lot of folks both black and white might write the whole thing off as a rinky-dink taboo attraction to the forbidden “other”—with the thinking being that the “other” is the entire black American nation. That’s not entirely accurate. Black as they are, the blues are also part and parcel of America’s outlaw ethos: the first bluesmen were primarily jobless, itinerant musicians whose lyrics and lifestyle were an obvious liability to black America’s emergent race-building consciousness in the late 19th and early 20th century. The bluesman was not pulling himself up by the bootstraps, and the music would not or could not be considered “a credit to the race” until decades later. Today, of course, famous bluesmen open tourist traps in Times Square.

“The blues are completely honest. It’s just perfect to me,” says Jack, matter-of-factly. “Every song can only be one man’s story against everybody’s.” One man’s story against everybody else’s! Jack White says he grew up poor and white in a neighborhood called Mexicantown and that he first started listening to the blues when he was the only white kid at his mostly black high school that didn’t wig out. But who knows if he’s telling the truth? Just what, exactly, did Jack White do to be so black and so blue?

“The blues are completely honest. It’s just perfect to me. Every song can only be one man’s story against everybody’s.” —Jack White

This identity politics line of questioning is for squares and comes out of the cross-roads where the basic American obsession with authenticity meets the country’s central personality trait of near-pathological lying. It’s also patronizing racism, American-style, that the king of the Delta Blues can sell his soul to the Devil in legend but Jack White of Detroit can’t call his ex-wife his sister. The White Stripes—like the blues—are unconcerned with such a trick bag and so they exist squarely outside the matrix. Outside that system, honesty is urgency as much as it is truth-telling, and Jack White sings like there’s things about him and Meg and they peoples that they desperately want you to understand, even if he can’t or won’t make it exactly plain for you. And if you listen to their albums and can’t tell what’s a White Stripes song and what’s a cover, that’s the interstitial space in which the blues have always existed. At their best, the blues themselves are a question, a sort of black American koan that take a long time—perhaps a lifetime or just the 70-some odd years between the first recording of Son House’s “Death Letter” and the White Stripes version—to really understand just one man’s story. It looked like ten thousand people gathered ‘round the burial ground/ I didn’t know I loved her ’till they began to lay her down.

And if the White Stripes are a little self-aware, as they were when drawing parallel between the blues and Holland’s De Stijl art movement for the title of their second album, they are not self-consciously so. Detroit as a city is almost completely unself-conscious. The girls there eat red meat, drink dark liquor and chain-smoke Camels, and the guys are probably still cool with their moms, have day jobs and girlfriends and peculiar ways of handling cigarettes and the smoke they produce. No one seems to have a cell phone and when you go to the record store there’s no Latin section and there are actually street signs that point the way to Mexicantown. As late as last November the White Stripes were playing $5 shows ($1 for students) and when the band records some songs for a local PBS station and “The Big Three Killed My Baby” is cut from the program because General Motors sponsored the show, no one blinks twice.

“We never set out to say, ‘Okay, we’re gonna be a garage rock band and that’s it—we’re gonna use the same three chords over and over again. We’re gonna make six albums and then we’re gonna stop.’ We never said that,” says Jack. “We never wanted to play for the same 50 people all the time.”

“And that’s what you could say about these last few years in Detroit: a back-to-basics look at what music means.” Jack continues, “What does it actually mean? With all its faults and fakes and videos and clothing and album covers, what does it actually mean? It’s just looking towards getting back to what it really was, not looking back and reminiscing as much as getting things back to normal again.” There is no irony in Detroit. When the White Stripes can turn down a million dollars from Gap and Jack still says there’s no hope in the city, it calls to mind something Detroit techno DJ Mike Banks said or wrote somewhere: No hope No dreams no love My only escape is underground.