When Producers Are Puppet Masters

With the Kesha case, Dr. Luke has become our foremost svengali. So—what’s a svengali?

He was “a tall, bony individual,” George du Maurier wrote in his 1894 novel Trilby, “well-featured but sinister.” He had “bold, brilliant black eyes” and a “thin, sallow face” and a “beard of burnt-up black which grew almost from his under eyelids.” And “he went by the name of Svengali.”

That is the first-ever appearance of a character that has been both obscured and made elemental by the passing of time. Du Maurier’s Svengali was a diabolical, explicitly anti-Semitic caricature with no shadings as to his character. It was with pure villainy and literal hypnotism that he transformed our titular heroine—the joyous, poor Parisian milkmaid Trilby, with whom everyone fell in love—into a dead-eyed international singing sensation. Throughout the glorious opera houses of Europe, and all while under his masterful trance, she became known as “La Svengali,” and she bred a craze: “Svengalismus.”

Trilby was a populist smash in its time. It birthed a musical, a stage play revived repeatedly over decades, and at least seven cinematic adaptations. And somewhere along the way, as its lore grew, the prototype gave way to an archetype. Most of us don’t know du Maurier’s tall, bony individual. But we know the svengali: the dark figure that, with undue control and perilous personal cost, manipulates another into greatness.

A century and change since it first appeared, the idea of the svengali worms its way into wherever power dynamics exist: national electioneering, international espionage, the break room at the Tommy’s Pretzel Hut at the mall. But it still seems to have its natural home in our most individualistic mass-market art form. That is to say, the truest form of the svengali remains that of the master puppeteering the pop star.

How does the svengali manifest itself in today’s pop? And why is it still so present?

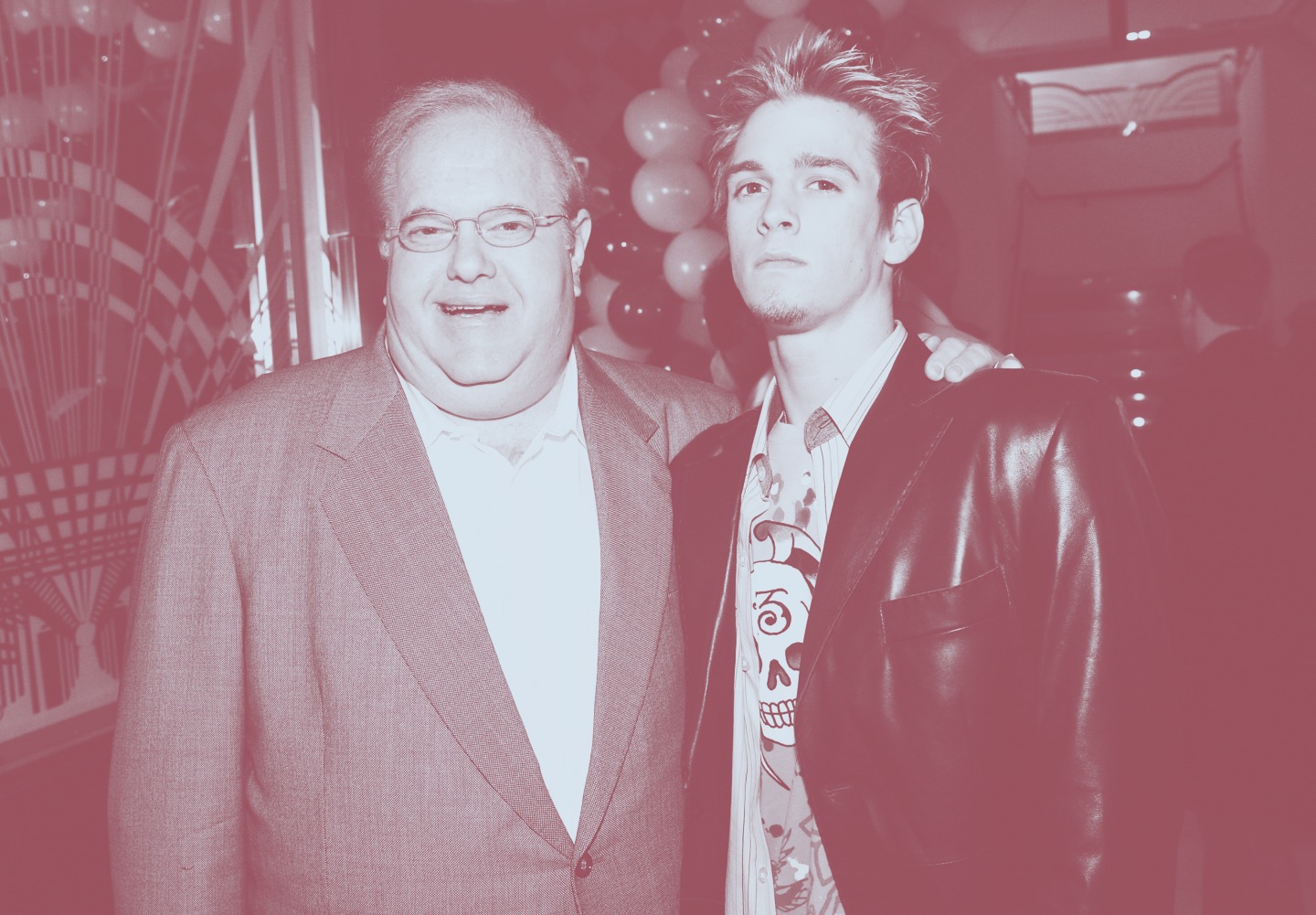

Lou Pearlman and Aaron Carter, 2005

Evan Agostini / Getty Images

Lou Pearlman and Aaron Carter, 2005

Evan Agostini / Getty Images

To chop it up bluntly, we can split up our pop svengalis by their respective levels of malice.

First, a small step into the murk. These are svengalis who are technically well-intentioned, yet they are still somehow suspect in their position of control.

Consider Scooter Braun’s shepherding of Justin Bieber: it was only when Bieber shook off the Scooter yoke and ran wild, driving fast and peeing into buckets, that we realized how firm that yoke once was. Look, as well, at the young Rick Rubin. He was instrumental in transforming the Beastie Boys from hardcore kids to a hip-hop phenomenon: he gifted them the big drums of their early sound; he bought them matching Puma tracksuits. But the Beasties would grow to resent his outsized role and his egging-on of boozy frat-boy antics. In order to recuse themselves of Rubin’s control, they would quit Def Jam in its iconic prime and run off to California.

Next, we take an incremental step up, into actual criminality. Here we have the likes of Cash Money’s Bryan “Birdman” Williams, who groomed New Orleans rapper Lil Wayne to stardom from the age of 11. Wayne would grow to feel that Birdman was the only proper father he’d had. But Birdman allegedly ran his business like a mob outfit, which meant there wasn’t much of an accounting department; one-off lavish gifts were said to come much more regularly than royalty checks. In January 2015, the son would sue the father over withheld payments for $51 million.

Worse: Lou Pearlman, who initially funded the Backstreet Boys and *NSYNC with money generated from a pyramid scheme built on blimp rentals—then later stole millions from the boys to desperately prop up said blimp scheme. Justin Timberlake has said working with him was like “being financially raped by a Svengali.” And it gets crazier: when the warrant for Pearlman’s arrest for fraud was issued, he fled to Jakarta, where he was eventually found registered at a hotel under the name “A. Incognito Johnson.” He’s currently in federal prison in Texarkana, Texas, where he swears he could whip up a new hit boy band if just given regular access to a phone line.

Lastly, a look at the most dastardly: those whose prodigious talent is only topped by their psychosis.

Phil Spector’s here. In the ’60s, his obsessively deliberate “Wall of Sound”—layers and layers of strings and guitars—elevated girl-group pop into high art. But it was with creeping dictatorism that he created a sound so heart-quaking and eternal. Five years after Spector produced “Be My Baby” for The Ronettes, he married their lead singer, Ronnie, virtually imprisoning her in their home. “I was brainwashed, he wouldn’t let me out of his sight,” Ronnie has said. “All he wanted me to do was stay at home and sing ‘Born to Be Together’ to him every night.” He told her there was a gold coffin in the basement, and that “the only way I would ever leave him would be in that coffin.”

Ike Turner, the man who may have invented rock & roll, also joins us here. His “machine-gun bursts of tortured, quivering chordal slams,” wrote the Los Angeles Times’s Robert Palmer in 1993, “were like nothing heard before” and “have rarely been equaled” since. But while Ike was possibly a genius, he could not sing. He found his greatest muse in Anna Mae Bullock from Nutbush, Tennessee—the woman who would meet the world as Tina Turner. Ike’s vision, as once summed up by Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen: “The band plays tight; Tina goes berserk.”

Years later, rendered utterly ignominious by Tina’s accounting of his brazen philandering and his physical abuse, Ike would still take outsized pride in his role in the crafting of his ex-wife’s famed showmanship. “The lights came down on her, there was no spotlight on me,” Ike told SPIN in 1985. “She’d stroke that mike and shit like that—I was the one who told her to do that…And Tina being the sex symbol, that’s what happened. People think that came from the visual part of an Ike and Tina show, but man, that’s not it. I styled her that way—I made it happen. I gave the drummer the signal, and it sounded like a gunshot.”

And now threatening to enter history alongside the notorious Ike and Phil: Lukasz Gottwald, the ubiquitous and powerful hitmaker known as Dr. Luke.

Dr. Luke and Max Martin, 2011.

Kevin Winter / Getty Images

Dr. Luke and Max Martin, 2011.

Kevin Winter / Getty Images

In the winter of 2016, the legal battle between Dr. Luke and his former protégée Kesha Sebert, once known professionally as Ke$ha, dominated music-industry news. Kesha has alleged that over the decade of their collaboration—which produced chart-topping hits such as “Tik Tok” and “Die Young”—the producer abused her both verbally and sexually. In a civil lawsuit filed in hopes of voiding her contractual obligations, Kesha made a string of nightmarish allegations, including that she was once given what Dr. Luke called “sober pills” and woke up the next day naked in his bed without memory of the night before.

Dr. Luke has denied all charges, tweeting at one point that Kesha was “like my little sister”; he’s suggested the charges stem from a misguided attempt at a more favorable contract renegotiation. In February, a New York Supreme Court judge denied an injunction which would have allowed Kesha to release music out from under the jurisdiction of Dr. Luke’s Sony-backed Kemosabe Records.

This is a story that, if it didn’t feel so horrible, would sound clichéd. Kesha was 18 when Luke signed her, an aspiring starlet from Nashville with a country music background and a lovely natural singing voice. She dropped out of high school, moved to L.A. When she broke through a few years later, it was as an unbathed, whiskey-loving, quasi-rapping delinquent.

Dr. Luke was a protégé once, too. His mentor was Max Martin, the Swedish songsmith who has dominated the pop landscape for nearly two decades. From the outset, Martin was eager for total control: Robyn, the dance-music experimentalist, was in the Martin camp as a teenager, but bristled under his command and often shook off his directives (“I really wanted to stand on my own two feet,” she would later say). In the late ’90s, Jive Records introduced Martin to their new artist: the then-unknown, 15-year-old Britney Spears. And he found his blank canvas.

All those years later, Luke would too. He’d crafted smash hits before, for Kelly Clarkson and Katy Perry. But Kesha was the first act that Luke had discovered and developed himself; to Luke, this seemed to mean he had a natural ownership over Kesha’s career. And that’s where the svengali archetype really kicks in. We may never know the details of Dr. Luke’s alleged sexual assault. But we can understand the dynamic at play in this contentious relationship: it’s that of a powerful, highly connected older man and a younger woman being denied her agency.

Kesha’s lawsuit describes a working relationship in which she had no true control over her creative choices or her public persona. Kesha says Dr. Luke made his control explicitly clear: during one spat, according to an affidavit, he icily told her that he could “manipulate my voice…in his computer…to say whatever he wanted.” And when taking aim at Kemosabe, the lawsuit paints the record label as less of an unwitting participant and more of a pimp. The label, the suit says, “provided Dr. Luke with unfettered and unsupervised access to vulnerable female artists beginning their careers…who would be totally dependent upon Dr. Luke for success.”

This is a formulation that is maddeningly easy to grasp. Because this is how our pop music naturally functions: the star at the front of the stage dancing and singing gets the mass adulation and the magazine covers; the operator behind the curtain maintains the control. This is how we—the engaged fans, informed as to the full machinations of the song machine—generally believe the best pop music is made.

Svengalis are persuasive not just because they promise money and fame; they are persuasive as well because they promise grandness. That’s the currency of pop. An aspiring pop star doesn’t just want red-carpet glitz: they want the stature, the legacy, the iconicity that pop can grant.

An actor can dazzle millions with a vulnerable debut performance. A novelist can find awards and audience with direct, thinly-veiled memoir. But the pop star, we know, never just arrives fully formed. Even when the pop star’s rallying cry is individualism above all else, we know, there has been a process.

Which means the string-puller—the one who orchestrates the process—is elemental. In other artistic fields, the svengali occurs regularly. In pop, the svengali is baked into the system.

“In other artistic fields, the svengali occurs regularly. In pop, the svengali is baked into the system.”

Some of those svengalis are, possibly, true psychopaths. Decades after his abuse of Ronnie, Phil would be convicted of killing Lana Clarkson in his California home by shooting her in the head. This was a tragedy made worse by its foreshadowing. For decades before, tales of an arms-crazed Spector pulling guns in studio sessions—with John Lennon, with Leonard Cohen, with The Ramones—were passed along and gawked at.

Most of the time, though, svengalis seem driven by something less than out-and-out mania: they believe their control is warranted by their singular talent and their uncompromised vision. And in that, they find some kind of complicated redemption.

Is abuse justified if it produces great art? Most of us wouldn’t have a hard time answering this question. The respective greatness—whether it’s Fellini’s La Strada or Kesha’s (truly great) “C’Mon”—is irrelevant. Human abuse cannot be justified by product.

The svengali would disagree. And in that, they are cheered by the public response. As long as the true extent of the control is kept secret, the art can stand on its own. The fans love it, and the svengali is proven right. Once the control is revealed, the fans turn on the svengali. And the svengali is rendered confused, dejected, bitter, and combative. The svengali is left shouting, from deep within the bowels of theoretical gated mansions, “But you loved me before you knew!”

Take Ike: to the end, he was unrepentant. He was, he believed, the only one who understood how hard it was to create a force as commanding as the young Tina Turner. He was, he believed, the only one who could have pulled it off. And years later, some music historians would grapple with a problematic, widely shared thought: that the brilliant, violent Ike Turner had died not being paid his proper due. Wrote the LA Times’s Palmer, “perhaps [Ike] played the behind-the-scenes svengali too seamlessly for his own good.”

Kesha’s case has brought a wave of discourse about assault and the ugly things that happen in the back corridors of power, and about how and why victims are believed. It’s also brought attention to this storied tradition of svengalism—and reminded us quite how rife it is.

Even with Kesha’s case in the news, is it hard to imagine, as we speak, her same trajectory reoccurring? A high school dropout moving to California and throwing her lot in with a producer she perhaps should not be so trusting of? There will always be raw talent. And there will always be bony individuals believing they should, by any means necessary, shape raw talent into supernovas.

Let’s go back to du Maurier. He was the inventor of the svengali, and so the svengali’s original, fiercest critic. But even he fell prey to the svengali’s defense: that in the songs, there is salvation.

By the end of his book, everybody dies. Svengali has a sudden heart attack mid-performance; finally free of his hypnosis, Trilby dies soon after of a vaguely defined illness. We, the readers, are meant to be happy that Trilby moves on with some measure of peace. But there’s a lamentation too. Despite his lecherous treachery, despite his cowardice and greed, we’re left feeling regret that the music that Svengali svengali’d into existence is no more.

“Her voice was so immense in its softness, richness, freshness, that it seemed to be pouring itself out from all round,” du Maurier writes. “If she had spread a pair of large white wings and gracefully fluttered up to the roof and perched upon the chandelier, she could not have produced a greater sensation. The like of that voice has never been heard, nor ever will be again.”