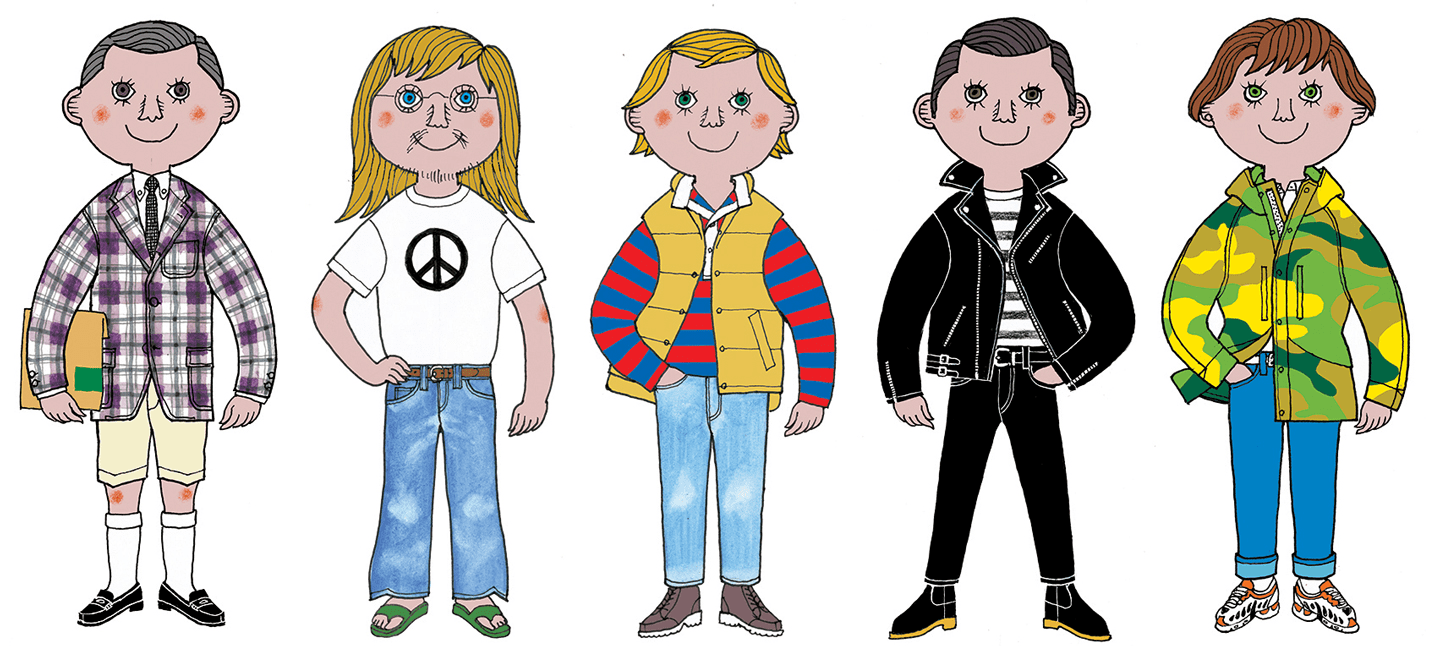

Kazuo Hozumi

Kazuo Hozumi

I can get pretty obsessed about a new piece of clothing. By now, the routine is familiar: the initial spotting from afar (and perhaps the sneak iPhone pic or two), the silent fist pump when I find out where to cop, the sweet euphoria when the purchase comes through, and finally, stepping out into the sunlight glowing with that first-time-on triumph. And then I wear the shit out of it. It’s magical.

So I can only imagine how Kensuke Ishizu felt when he first encountered Ivy League style. Back in 1959, the Japanese designer was traveling the U.S., seeking inspiration for his ready-to-wear clothing company, VAN Jacket, when he decided to visit Princeton University, the place he’d long heard was home to the effortless Ivy League look: undone ties, simple white button-down shirts, the coat with elbow patches slung over the shoulder. He went home, took that preppy look, and changed the course of Japanese fashion forever.

Or at least one branch of it. In a new book called Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style, author W. David Marx traces all the times that modern Japanese fashion went against the grain to mimic, adopt, and build upon American Traditional style (what he refers to as “ametora”), pushing it further than Americans could have ever imagined. It wasn’t just Kensuke Ishizu and VAN Jacket with their Ivy League looks, but also Hiroshi Fujiwara and Goodenough and Nigo and BAPE for streetwear, Evisu and Kapital for denim, and more. If you’re stoked on streetwear and its origins, read this book.

Recently, I got the chance to talk to Marx, who now calls Japan home, about how his own interests in Japanese fashion first developed, the relationship between music and fashion, and how rule-breakers make the world go round.

When did your interest in Japanese fashion first develop?

I grew up in Pensacola, Florida. Pensacola has a sister city exchange program with a small town in Japan, so I went there when I was in high school. I loved American music and TV and knew they were a big force in a lot of the world, but what I liked about Japan was that when you went to Japan, everything was Japanese. All the stars were Japanese. Obviously American movies did well and American music did OK, but there was this huge world of Japanese pop culture that was completely unknown outside of the country. Even just the commercials on TV felt like they had their own logic and rhythm to them. They didn't feel like they were ripping off American commercials or dubbing American TV shows. Everything felt a little off and interesting.

I got very into Japanese pop culture and went to college and studied East Asian Studies. When I went to college, in 1997, 1998, the Japanese economy was already on the down. The bubble had already popped in Japan, and the anime boom hadn't started yet, so most freshmen were starting to study Chinese, thinking that China was the future. People weren't studying Japanese to make money anymore. I was one of the very few people in my classes who wasn't a grad student. I would just bug my professors about Japanese song lyrics and stuff. I was very into bands like Cornelius and Buffalo Daughter.

So your interest in fashion developed from music initially?

I grew up being obsessed with music rather than fashion. Fashion to me meant, like, Cindy Crawford's House of Style or whatever. Just something so unbelievably unrelated to me that I just had zero interest in it. I guess I was always interested in how subcultural fashion worked, in a vague sense. And then when I went to Tokyo for the first time I realized, wow, everybody is very, very, stylish, and everybody is wearing very stylish clothing that is almost a year or so ahead of the U.S. Dark denim was in that year, in 1998, in Japan, but you couldn't buy a pair of dark denim pants at the Gap in the U.S. until maybe six months later. Just that made me say, “Oh, there's something going on here.” And then when I started waiting in line to buy a Bathing Ape shirt and it took three hours, I came back and said “I’ve stumbled onto something quite interesting.” Bathing Ape hit that sweet spot for me as a Cornelius fan, in that it was kind of fashion that was related to the music. Streetwear to me was the extension of being into music, and then the fashion itself kind of has its own story. I went from there.

How is this relationship between music and fashion unique in Japan?

In the U.S. and U.K., music was always primary and clothing was secondary. There are looks like punk and mod where the fashion is more enduring in some ways than the music, but it's really hard to talk about punk without talking about the music. I mean, it's impossible.

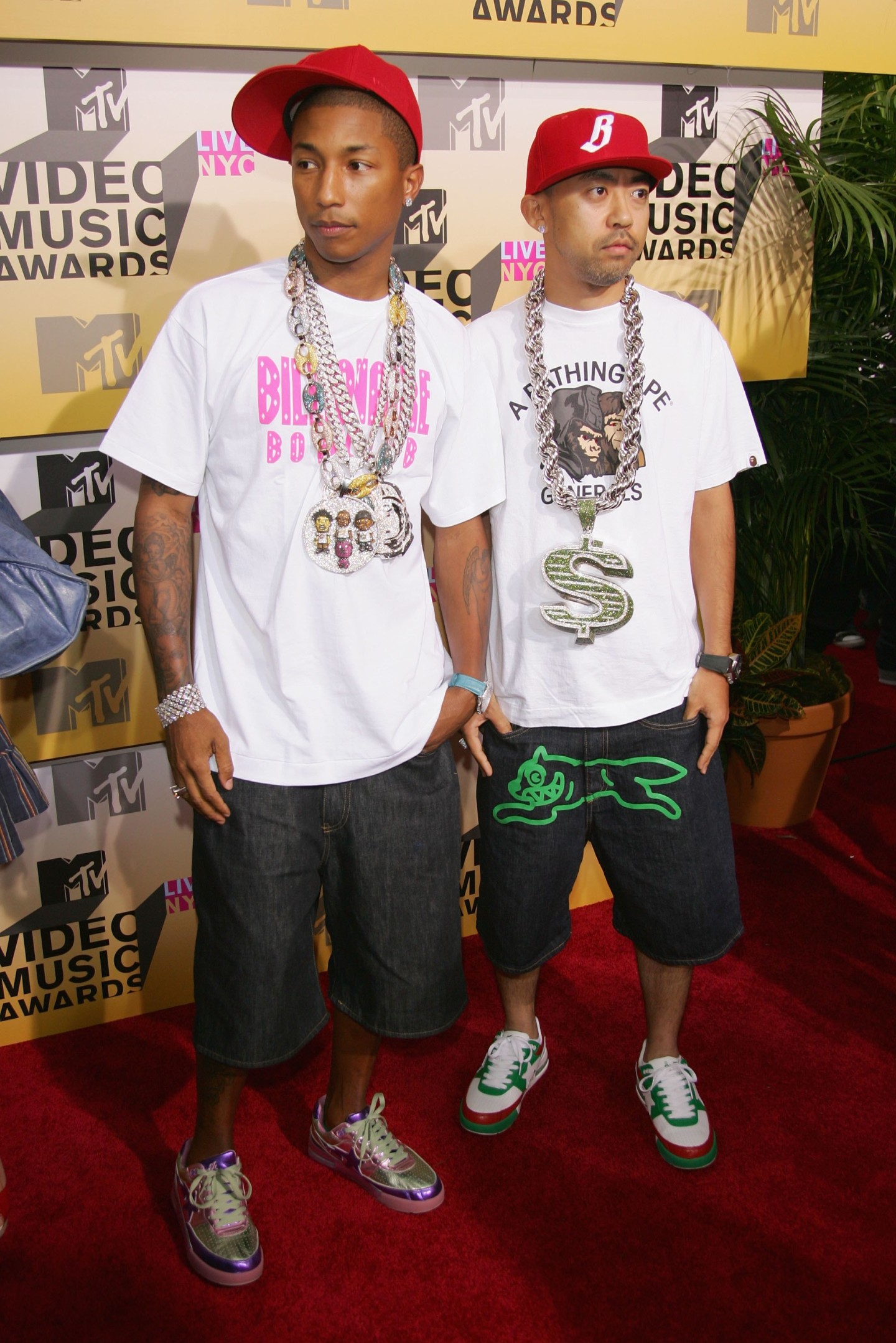

I think in Japan that the fashion is primary, and the music is secondary. So with Ivy style, there were some people into jazz, there were some people into folk, but there was nothing like, “If you wear Ivy, you go to this jazz club and you listen to these jazz bands.” It was kind of scattered. With streetwear, obviously Hiroshi Fujiwara was one of the first people to bring hip-hop to Japan, and there was a strong tie to hip-hop, but at the same time, he loved to play guitar with Eric Clapton. Hiroshi Fujiwara and those guys, they're obviously tied to hip-hop, but they love a lot of other stuff. It's almost like the music came out of a fashion subculture.

Evan Agostini / Getty Images

Evan Agostini / Getty Images

Despite different Japanese fashion subcultures’ rebellious origins, there are still often strict rules. Why do you think this dynamic exists?

There are two mechanisms that create that dynamic. The first is that many of these styles are not rooted in some sort of organic lifestyle. Like, surfers wear surfer gear because they're on the beach, and so the idea that surfers develop their own clothing is pretty natural. When instead you teach people through magazines [like VAN Jacket initially did with Ivy style], this is what surfer clothing is, it's very likely that they're going to buy the exact same things the magazine says are surfer clothing. Subcultures in Japan are taught by the media because they're not native to Japan—they were influenced by the West—so you just end up with this type of order.

The second is: for the real, organic subcultures in Japan like the motorcycle gangs, they tend to have a uniform to mark themselves away from society. It wasn't like an actual specific uniform, it was more like their hair was a certain way and they wore clothes that were not worn by normal people: leather jackets or Hawaiian shirts or things that just had an air of delinquency to them. But as time went on in the ’90s and you start actually developing bosozoku motorcycle gang magazines and stuff, everybody just starts wearing these uniforms. Like uniform uniforms. They're actually based off janitorial uniforms. They would wear those and put these huge slogans on them in embroidered gold and red. And so, you have this subcultural force where people want to look the same to mark themselves as a distinct group away from mainstream society. And I think that in Japan there is an emphasis on process and detail, so you just end up with people doing a better job at being pretty serious about dressing a certain way.

At the same time, I think that there's this idea that in Japan, the way to success is following convention and being a good boy and not questioning things and all that, and I think that all of the examples in this book show that real cultural change happens when someone decides to break the rules and break conventions. They were often told "You can't do these things" and they would go do them and they succeed. These are all people with great entrepreneurial spirit, for a word we would use today. They just wanted something different and were fine being called crazy.

There was definitely a strong DIY vibe at the beginning of each new Japanese style movement. Often it was head up by one individual at a time.

Until now, I didn't really like this model, “the great man model of history.” I was more interested in how change happens from social models and things like that, rather than people. But in the research of this book, I just realized how many times it was literally one person's decision to do something, and that person's life and the decisions they made led to these moves. There would've been new fashion in Japan without Kensuke Ishizu of VAN Jacket—like, there would've been something, but the fact that it was Ivy was very much him. He made a decision to do Ivy in a way I don't think anyone else would have because it just didn't seem that obvious to anyone else at the time to do Ivy. At first, when he heard about Ivy League style, he even thought that it would never work in Japan because Japan seemed much more interested in European fashion. So that's one example.

Harajuku and rock & roll, all of that happened very specifically because of one guy who was just doing something different from other people. There would be no streetwear scene in Japan if it weren't for Hiroshi Fujiwara. He, personally, by going to London and meeting Malcolm McClaren and going to New York and bringing the first hip-hop records back to Japan, he was a conduit in a way that other people weren't.

But as time goes on, because the Japanese fashion market has become so complex, it was very difficult to pin things down on one person. You'll see in the last three chapters, or at least two chapters [about vintage and replica denim and the idea of exporting ametora], that I can't follow one person because one person doesn't tell the whole story the way I did it from the beginning.

Yankii teens from Otaru in the 1980s wearing altered school uniforms and regent hairstyles. https://t.co/0vF7SZm2yV pic.twitter.com/RYZAxlUTh4

— W. David Marx (@wdavidmarx) November 22, 2015

Do you have your own personal philosophy on clothing and style?

The great irony is when I grew up in the South, and my dad’s a professor, so he was just kind of university style which is very Ivy, very preppy which was like the base of my wardrobe as a kid. Not like I chose any of it, but what was chosen for me. And so much of that is now kind of back. A lot of my style is obviously inspired by being in Japan, and I buy a lot of Beams Plus. A lot of my shirts are Kamakura shirts. I have to get all of my shirts custom made anyways because I’m very, very long armed. I have this weird mix of styles that represents my style journey, but it is to me so much by going to these roots. I think when people are, like, “going back to my roots,” it’s usually some style choice they made themselves, but I’m going back to how I dressed when I was 12 years old. I have a lot of friends who are like, “Yeah just wear a uniform.” It’s very cool to be nonchalant and just wear a uniform, but I’m kind of the opposite. If I have a shirt that I bought and I don’t wear it enough, I kind of feel bad for it. I try to rotate my clothing quite a bit so that I give it equal love.