It’s rare that a buzzy east London bar will be covered with political posters, but on a Friday night in early June, the walls were lined. Behind the beer pumps, a poster read in bold Helvetica, "For 60 years the E.U. has been the foundation of peace between European neighbours." A DJ playing disco and house wore a slogan t-shirt bearing a similar message, and in a bathroom stall, another poster had been decorated with a lipstick heart.

The campaign was the work of the London-based artist Wolfgang Tillmans. Born in Germany and based in London for the past 26 years, his current project aims to raise awareness of the upcoming E.U. referendum in Britain on June 23, and lays out what is at stake if the U.K. leaves the union. “Please feel free to share these posters,” Tillmans wrote in a statement upon releasing the imagery (downloadable here) on April 25, 2016. “They work as print your own PDFs, or on social media, or in any other way you can think of. I consider them open-source, you can take my name tag off if more appropriate.”

It’s unusual for fine artists to give away their work for free, let alone to allow it to be reproduced uncredited, but Tillmans and his work are rooted in DIY culture. Underground music and gay communities have always been featured in his photography, from works like 1989’s Love (Hands In The Air), in which a female clubgoer is enraptured while grasped by unknown hands, to recent editorial projects with LGBT activists in Russia, and artists like Shayne Oliver and Arca.

In 2000, Tillmans was given the U.K.’s most prestigious award for visual art, the Turner Prize. He was the first non-Brit (and first photographer) to receive it. At the time, the TATE gallery director Nicholas Serota said: “It’s a question of recognizing that the culture here is much richer than we could define by those who have simply been born in this country.”

As the E.U. referendum approaches, in a year where right-wing leaders are finding a new footing across the western world, this richness seems ever more under threat. Reached by phone, Tillmans spoke slowly and with consideration about his personal motivations for the project, how leaving the E.U. would affect underground culture in the U.K., and what we can all stand to lose.

Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans

Was your aim with this project to reach younger voters, or creative folks?

The official campaign has to be focused on one slogan and one message, which makes sense, but there are so many messages and things could be much more multifaceted. And visually, it could also look a bit more cutting edge, challenging, and interesting.

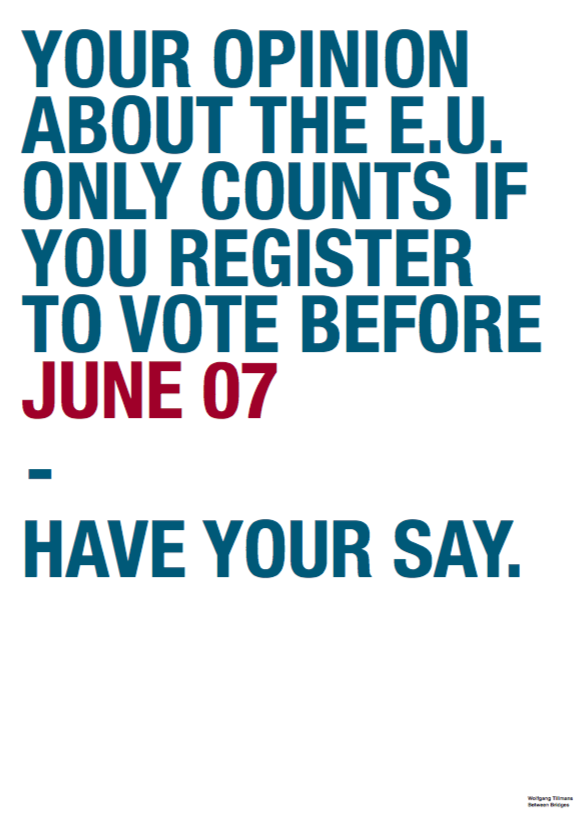

Of course, the big problem with elections is that young people tend to not vote, and young people tend to be most Europe-friendly because that is their experience. They go for the weekend to Berghain or they go for the weekend to Barcelona, and they don't want that to be taken away from them. The single way to make sure that you stay is to vote. Register by June 7, and then actually go out on June 23.

I think there’s a lot of confusion about what leaving the E.U. would actually mean for people in the U.K.

There is a lot of speculation about how it might affect Britain, and who it would affect. The truth of the matter is that actually no one knows. Even the Leave campaign does not have an exit strategy, and they have no idea how this could work. That is a very bizarre thing, to take a country into uncharted territory when the system is not broken at all.

The E.U. is like an unloved parent who will always be criticized, but actually provides the backbone to a lot of what we take for granted. When you take that away, how would travel work? How would shipping goods work? Certainly students, for example, would not be able to go and take part in the Erasmus student exchange programme. [Note: this has been contested by commentators such as Gisela Stuart.] Much more grave is the message that it would send to the other 27 nations: “Nothing works, we really have to get out.” That would put a lot of negativity in the world. It’s not just going into your shell, but it’s also a snub.

My biggest point of why I feel so passionate about it, is that if Brexit happens it would send a message of support to the enemies of European values, like extremists of all colors and variety of sizes. Of course, Russia and Putin have the greatest interest in weakening the E.U. The whole rhetoric of the Leave campaign has become so nationalist, and nationalism is slightly close to potentially racist and potentially anti-Islamic intolerance. We have lived peacefully in an multi-ethnic society in Britain for decades, and we are moving on into the 21st century. It’s not a moment to say now is time to purify Britain.

Wolfgang Tillmans

Carmen Brunner

Wolfgang Tillmans

Carmen Brunner

"Today a lot of musicians don’t dare to side with something unless it’s very safe, I think for fear for losing out commercially. I find that worrying."

Why was it important to the project that these works were freely downloadable?

It was really the urgency of the matter that convinced me to aim for a wide distribution as possible. It was calling for extraordinary means — new means. I'm not a digital native, but I am really thrilled with how the whole approach worked, with over 25 different posters and images, and t-shirts which then circulate the message on social media, like with Vivienne Westwood this week.

I wonder whether someone like Vivienne Westwood would have worn a government-produced t-shirt.

That’s the thing. The only campaigns that seem to work now are coming from people like you and me who take the courage to speak their mind. I have never done this before, because it’s always a little bit awkward to stick your neck out and put yourself behind a cause. But I really feel that this will affect our lives so badly and will send such a message to all those who want to cause more radicalization in the world. When you look at the list of people who want Britain to leave, it’s a nightmare: Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen...

What’s at stake for gay and queer people if Britain leaves the E.U.?

The freedom of movement act is amazing. In the E.U., gay or lesbian couples live, just like any couple, and they can live in their country of choice. There isn't another block of nations in the world where that happens. The E.U. is a huge promoter of human rights, for example in trade agreements. They recently had a trade agreement with Colombia for example, and they put in non-discrimination and other clauses that simply protect people’s rights. When you have 508 million people represented by one body, it is a completely different thing than [Britain’s] 65 million people.

Do you think your fellow artists doing enough to respond to this issue?

It has taken a while for the creative community to wake up, but now [my] colleagues like Rachel Whiteread, Tracey Emin, Antony Gormley, Anish Kapoor, and Michael Craig-Martin, are getting very vocal as well.

What do you think of how musicians are incorporating human rights issues into their work, like M.I.A. with “Borders”?

M.I.A is a surprisingly rare example. I always loved protest songs, it is a beautiful genre, and it uses the power of music to such good ends. Today a lot of musicians don’t dare to side with something unless it’s very safe, I think for fear for losing out commercially. I find that worrying. In the dance scene, for me house and techno were fundamentally political movements. A great uniting humanist experiment and endeavor — maybe not the promised land like Joe Smooth’s song, but definitely trying to live peacefully together and not be governed by fear. As a gay person, that is somehow with me much stronger because I grew up in a time when there wasn't equal rights.

I enjoyed your recent editorial work with Shayne Oliver, for Fantastic Man, and Arca, for BUTT. What about their creative community feels fresh to you?

I really enjoy that gang, because they really are fearless, and successful at the same time. They are also not afraid to cross gender and masculinity stereotypes, which in the gay world in the last twenty years has become an extreme monoculture.

It’s like the clone thing all over again.

That is something I find so boring. In the ‘80s, you never looked at how many muscles somebody had. It was being about individualistic as possible and sharing that difference. [But] it is nice to see how it is coming back in metropolitan places, and how some players from those places are making it in the mainstream, or close to the mainstream, like Shayne.