Photo by Oli Scarff

Photo by Oli Scarff

Meek Mill’s 2014 calendar year was a nightmare. Following the recording of Dreams Worth More Than Money that year, he was sentenced to three to six months in a Philadelphia prison for “questionable behavior” while on parole, nearly delaying its release for 12 months. After violating probation for the fourth time, he was sentenced to 90 days of house arrest and six years of additional probation. The time Meek spent indoors had, it seemed, finally gotten to him. Ahead of the highly anticipated drop (the release date is pending) of his mixtape, Dreamchasers 4 (DC4), he announced via Instagram that the “extreme violence” — once an integral theme of his discography — would no longer be present in his work after DC4. Amidst intense racial conflict between black civilians and police officers, Meek felt inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement and wanted to turn away from using violent lyrics to explain himself. This shift publicly signaled the awakening of Meek Mill’s social consciousness: at minimum, the artist was now more aware of his position as a black rapper in a markedly anti-black society. But the actual motivations behind the switch up are, perhaps, a lot more pernicious.

In July, when Hot 97 host Peter Rosenberg asked longtime Meek Mill collaborator DJ Drama why the rapper wasn’t featured on Drama’s new album, Quality Street Music 2 — by alluding to a recent rap beef involving Drake — he provided some insight that complicated Meek’s change of heart. “There is a Meek Mill record,” Drama said, “but given his [legal] situation, respectively, his lawyers didn’t feel like, right now, might be the best time.” When Rosenberg pressed, Drama offered more details. “I’ve been kinda through this with artists before; [T.I. was] in somewhat of a similar situation. They’re very careful about the content, what’s said on records … But unfortunately, it’s due to some legal stuff.”

Meek Mill is on parole. He must, with some regularity, answer directly to the state, which, beyond its typical position as an omnipresent spectre in black civil life, has an additional claim to directly surveilling the rapper. With looming authority constantly checking in as to whether or not Meek is taking part in criminal activity comes the feeling of un-freedom — a state of being in which an individual’s rights are legally guaranteed and threatened simultaneously — that artists have tried to transcend. Even more telling, as Drama explained, is that he’d dealt with self-censorship with rappers in the past.

Photo by Daniel Shea

Photo by Daniel Shea

That black artists are surveilled by the state isn’t news. Black people, even before adopting the English language (thereby speaking themselves into an American existence), have grown accustomed to the presence of police. But there is a difference between policing the body — what we often mean when discussing modern policing — and policing speech. That legal distinction dates back to 1901, when the assassination of President William McKinley bolstered public support for the federal government to, for the first time since the 1790s, enforce the Alien and Sedition acts which specifically targeted individual opinion, participation in organizations, and activism without commission of a crime. Surveillance tactics and technologies were developed after the first Red Scare — a sociopolitical phenomenon meant to promote fear and anxiety of a worker’s revolution powered by Russian Communism between 1917 and 1920 — in 1919. That development would prove pivotal in how federal and state governments police black and brown communities into the present. So while police pursued Communist groups, the Japanese, Mexicans, and anti-British Irish, they specifically pinpointed black radical publications flowing through the recently established U.S. postal service. Black radicals got around this by passing out newsletters on the streets, in hushed back alleys, and clandestine meeting rooms, risking the battery of police batons. Being black meant free speech was never guaranteed — not by blood, or by right.

The connective tissue linking enslaved black people, heavily surveilled twentieth century black radicals, and black artists of the modern era is the potential (and often realized) threat of un-freedom.

Today, the state has sharpened its tools. Collusion in pre-Civil War America took place largely amongst white plantation owners, local militias, and federal lawmakers. The 1900s marked a historic moment in which state police, several federal investigative bureaus, and bigoted politicians made a concerted effort to stamp out all political misgivings (whether expressed artistically, editorially, or through civil disobedience) under the guise of keeping American democracy safe from Bolshevik Communism. In modern times, surveillance technologies — including the tapping of phone lines, cyber-spying, and city-funded CCTV cameras — coincide with America expressing concerted moral righteousness over seemingly non-democratic ideals and alternative forms of governing. In tandem with the police’s troubling relationship with social media giants like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, the state has crafted a near omnipresent regime of surveillance, reaching various forms of public and private media to police the morals of its civilians.

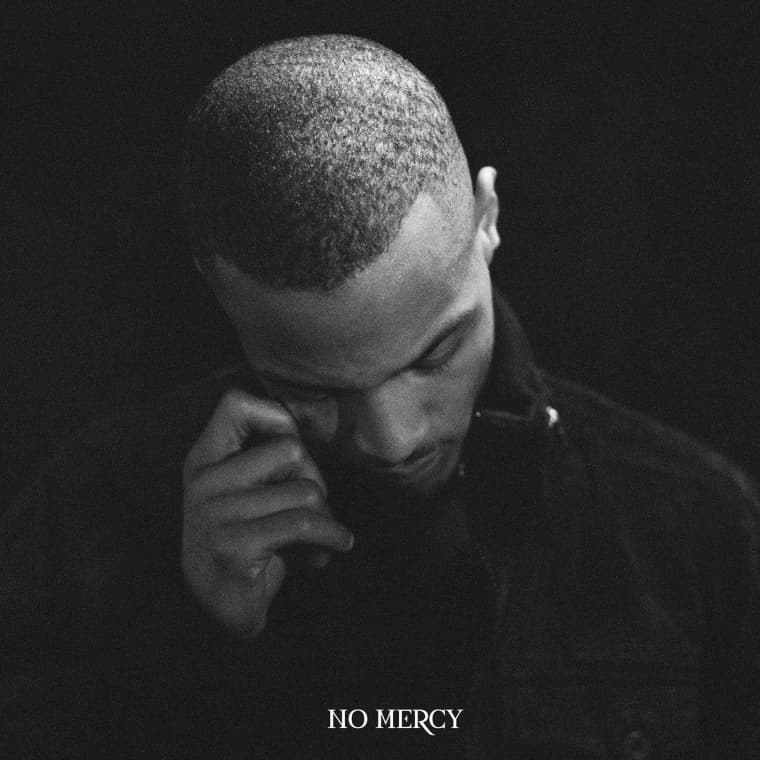

At one point or another throughout history, a handful of rappers have fit the un-freed description. Not only did T.I., a multiplatinum artist, change the name of his 2010 album from King Unchained to No Mercy because of legal pressures, the album itself lacked the urgency of his previous work because police pressure mandated a relative distance from the here and now. T.I. mentioned this change of lyrical place and time in a post-prison redemption interview with Larry King. When asked what he would do to ensure he doesn’t get pinched up again, the rapper said: “Just move forward and evolve personally and musically.” Movement begets evolution, and T.I., in consultation with lawyers, counselors, and publicists, told the viewing public that things would be different. Later in the broadcast, T.I. was seen speaking to a group of “at-risk” black kids in Atlanta during which he retired his inner G, saying, “Do I consider myself a gangsta til this day? I’m retired. I’m retired.” And it all became clear on the opening track of No Mercy, “Welcome to the World,” where he rapped: It’s my pleasure to welcome you to the world of/ Fast money, flashy cars, big guns/ Undone, threw away for the love of/ The Game…

Courtesy Atlantic Records

Courtesy Atlantic Records

Courtesy Universal Records

Courtesy Universal Records

This is the new T.I., the new un-free world of T.I., where the artist makes music influenced directly by the state. Hip-hop wasn’t meant to be created like this but, even in its infancy, the movement was being watched. The state gaze reflects the un-free civil life that initially birthed the genre. Chuck D’s timeless refrain that rap is CNN for black people is a continuous, sometimes cantankerous update on the ill-conditioned realities of the black present — the tone reflecting a constant frustration with being told freedom is within reach, but hardly ever fulfilled. The music speaks directly to state power about black reality. And that articulation, the literal act of rapping and beatboxing and head-banging, was rappers proclaiming not only their existence but their divinely ordained right to free will. But once an artist must negotiate public freedom with artistic un-freedom the choices are narrowed: however insignificant it might seem, these small linguistic changes can upend the scope of an album or a career.

The situation T.I. found himself in in 2010 wasn’t new at all. It’s one familiar to black people: somewhere between awe-inspiring appreciation of our various art forms and the ever-present possibility that our energy will be controlled, contorted, consumed, then done away with. Luckily he had a network of various revenue channels — from his label Grand Hustle to co-starring roles in Hollywood films like Takers and Get Hard to fall back on — but most black folk simply do not have that level of access. We are paralyzed in an un-free world.

The case of Lil Wayne is even more egregiously separatist. The question of why Lil Wayne would make a rock album — 2010’s Rebirth — after a nine-month stint in Rikers confounded a lot of people. It felt like a reach from an artist who had become satisfied with global prominence. Weezy’s public explanation was that his life most resembled a rock star so it only made sense to put out a rock album. Simple enough. But when pressed about the question by Billboard, Wayne offered more detail:

“When I said I was doing a rock album, it was about doing a freedom thing. This album isn’t hip-hop. When I do my Carter albums, I know I’ve got to rap, I know I’ve got to spit — I know the words I’ve got to say and the subjects I’ve got to talk about. I also know the things I shouldn’t say, the things I shouldn’t talk about. There’s none of those limits on this album. I say what I want, how I want. That’s what this album is: a freedom album. And rock is the avenue that gives you that freedom.”

There it is again. Freedom. Freedom after prison looked different to T.I. and Wayne, respectively. The former distanced himself from lyrical and thematic allusions to guns and violence; and the latter attempted to extract himself from the hip-hop prism altogether. Either way, freedom after prison for these artists meant creating separation between hip-hop, in all of its blackest and harshest realities. Even beloved trap pioneer, Gucci Mane, is showing signs of separatism. Though his post-prison album, Everybody Looking, largely continues on the subject matter of his previous albums and mixtapes, Gucci’s public posturing has significantly shifted. The same artist who impressed fans with the indelible rap analogy of “getting lost in the sauce,” was slated to headline an “All Lives Matter” concert in Biloxi, Mississippi. The world of the un-free is new and old. T.I., Lil Wayne, and, to a degree, Gucci Mane, used their talents and connections to break through the space that linked them to immediate and perpetual violence — only to be forced down to size.

Photo by Jason Nocito

Photo by Jason Nocito

The impact of prison time, and, consequently, surveillance on a rapper’s career is based on a number of variables. For instance, if an artist has already established a company or record label they’re more likely to focus on their business. T.I. dove into Grand Hustle Records, signing both Trae the Truth and Iggy Azalea in 2010. Weezy picked up a new endorsement from Samsung. A week after his release from prison, Gucci announced via Instagram that his new clothing line, Delantic, would be dropping soon. These guys would be fine as soon as the heat died down.

The impact of the state’s gaze on black artists career trajectory is even more dramatically tethered to gender. Unlike T.I., Lil Wayne, and Gucci, black women rappers aren’t granted the same access to opportunities in corporate America. Lil Kim never recovered, musically or personally, from the compounding effects of Biggie’s death in ‘97 and her perjury sentence in 2005 (though The Naked Truth sold a million copies, it was released the first day of Kim’s sentencing). Foxy Brown has had continuous run-ins with the law, in ‘97 and again in 2004, and her career resides in a shadowy murk. And Remy Ma, who completed a six-year prison sentence in August 2014, signed on to a reality show — a profitable, if odd, remix of the state surveillance ethic. If you’re going to watch my life, at least pay me for it!

Fans, of course, are impacted most immediately by the music. Unfortunately, there are have been a lot more post-prison albums that favor No Mercy than All Eyez on Me. But maybe the quality of an album following prison time doesn’t matter: after all, artists have made great albums in the penitentiary and under federal watch. What’s crucial is that rappers have the choice to include whatever they deem genuinely authentic to their narrative. Writing in 1966, Amiri Baraka noted: “The impulse, the force that pushes you to sing…all up in there…is one thing…what it produces is another. It can be expressive of the entire force, or make it the occasion of some special pleading. Or it is all equal…we simply identify the part of the world in which we are most responsive. It is all there. We are exact (even in our lies). The elements that turn our singing into direct reflections of our selves are heavy and palpable as weather.”

Perhaps these artists are doing that, perhaps the new post-prison freedom is exactly who they are in that moment and it is precisely their un-freedom that boils just under the surface of their sound. Still, these works are valuable in explaining how the state, through all of its surveillance tactics, dictates how artists express themselves.