Before two Baton Rouge police officers killed Alton Sterling in the early hours of July 5, 2016, with two shots fired from their service guns into his chest and back, he was a hustler. He scratched together something like $200 a day pushing copies of albums from local and national music acts. People called him the “CD Man.” “Sometimes I would go over there and just pop up on him,” says Arthur “Silky Slim” Reed, whose organization, Stop the Killing, Inc., creates anti-violence documentaries and DVDs using actual footage of street murders and police brutality shot in and around Baton Rouge. “And the first thing he would always say is, ‘Silk, I ain’t got your stuff out here!’”

It was Reed’s group Stop the Killing that captured and distributed the first footage of Sterling’s death. A volunteer for the organization happened to be passing by the parking lot of the Triple S Food Mart, where Sterling was killed, as the scene was unfolding. Aware of a confrontation between Sterling and the police earlier that day, she stopped to observe; as it escalated to a shooting, she captured the video on her phone, then delivered it to Reed. That footage, in conjunction the very next day with the police killing of Philando Castile in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, reanimated both the Black Lives Matter movement, which argues that there is a national crisis of police brutality targeted at black Americans, and the debate in which it swirls.

The names of the dead that have inspired the movement so far — from Trayvon Martin to Eric Garner to Walter Scott to Rekia Boyd to Sterling and Castile — are painfully familiar enough. Increasingly, so are the men and women who have captured the evidence of the killings. Without video shot by Ramsey Orta in Staten Island, Feidin Santana in South Carolina, or Diamond “Lavish” Reynolds in Minnesota, we would not know the exact circumstances in which Garner, Scott, and Castile, respectively, were killed. More than likely, we would not know of those killings at all.

The footage shot by bystanders can be seen as a reproach against the excesses of state power. It’s almost a parallel of the 2nd Amendment debate: like gun owners who believe staying armed is the only way to protect their private rights, amateur videographers cherish their power against government overreach. (Or of government omission: there is no police footage of the Alton Sterling killing because, the officers in the case contend, the body cameras they were wearing were dislodged during the incident.) Again and again, official police narratives have been contradicted by the work of quick-thinking witnesses armed with phone cameras.

When the Stop the Killing volunteer sent Reed the Sterling video, his first impulse was to sit on it. He thought maybe he’d use it in a future Stop The Killing documentary; he also considered the possibility that the police would themselves investigate the homicide, making the Stop The Killing footage unnecessary. “I was like, ‘Let’s see what happens,’” he says. Then Reed heard that the Baton Rouge Police Department was stating the officers opened fire only after Sterling reached for the gun that was in his front pants pocket.

Reed gathered a small crew in front of a large screen. “So we put it on,” Reed says, “and I don’t see him reaching for a gun. We rewind it. I don’t see him reaching for a gun. We all watching, like, ‘I don’t see him reaching for a gun! You see him reaching for a gun?!’ I see him putting his hands up and the officer pulling his hands back down. Like, ‘What the fuck is this? He’s not reaching for a gun! We can’t — we can’t — we can’t let this go like this.’”

By that afternoon, Reed was distributing the footage to scores of outlets, from the local TV news station WBRZ to the Associated Press. “We just start,” he says, snapping his fingers, “popping it out.”

Ramsey Orta and Eric Garner were friends. On July 17, 2014, the day Garner was killed in Staten Island, the two had gone to lunch and then returned to Bay Street, a central hub. A fight broke out in front them, and Garner stepped in to intercede. Garner was known to local police due to his side hustle, selling untaxed cigarettes. When the cops arrived, instead of targeting the instigators of the fight, they approached Garner instead.

As Orta would explain later, it was a regular practice of his to use his phone to capture incidents of police overreach. In his footage, as Garner is being tackled to the ground and put into a chokehold, you hear Orta’s voice saying, “Once again, police beating up on people.” Underneath is Garner’s voice: “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe.”

Orta shared the clip with the New York Daily News, and the killing of Garner went national. Soon thereafter, Orta says, he became a target for the police. On February 10, 2015, NYPD burst into his family’s home with one cop, Orta would later tell Democracy Now, holding out not a gun but the scope of his camera phone. “I asked them, ‘Why is you filming me?’” Orta said. “And he said, ‘You filmed us. Now we’re filming you.’”

His lawyers, William Aronin and Ken Perry, agree with Orta that the charges against him, which include weapons possession and drug dealing, are part of a calculated campaign of retribution. Nonetheless, Aronin and Perry told The FADER, they advised him to take a plea deal that will see him doing four years of prison time. As has been widely noted, that will make Orta the only person at the scene of Garner’s death to see the inside of a cell. (Daniel Pantaleo, the cop who killed Garner, was not indicted.) Said Orta, on the day the plea deal was announced, “I’m pretty much tired of fighting.” He reports to prison in early October.

Orta’s story is just one incident in a peculiar pattern of police scrutiny. Chris LeDay, a resident of Atlanta, was one of the first people to share the Alton Sterling video to a wide audience via social media on his @MobbGod Instagram account where he has over 15,000 followers. The next day, reporting to his job at the Dobbins Air Reserve Base, LeDay was arrested, held for 26 hours, then eventually charged for unpaid parking tickets. Kevin Moore, who filmed the arrest of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, was arrested weeks later at a protest in response to Gray’s death while in police custody. Diamond Reynolds, who used Facebook Live to stream the traffic-stop killing of her fiancé Philando Castile, was handcuffed after the incident, taken to a precinct, and held, separate from her 4-year-old daughter, for eight hours.

All that is partially why Reed’s plan, initially, was to keep both the volunteer that shot the footage and Stop the Killing anonymous. But the Associated Press insisted they could not run coverage without a signed release stating that Stop the Killing was the owner of the footage.

“It was a rough decision to make, but we had to get the story told,” Reed says. “I let everybody know, I’mma take the heat for it. Well, fuck it — here go a release.”

Weeks after, during protests in response to the death of Alton Sterling, Reed and a group from Stop the Killing splintered off the main action and headed to the home of the mayor, Kip Holden. Along with other protesters that day, some of them under the age of 18, Reed was arrested. He’s now being charged with a felony for four counts of contributing to the delinquency of a juvenile.

“It’s, um, kind of a bullshit situation,” Reed says. “But I’m also past three strikes, so a conviction would mean an automatic life sentence. So I gotta fight this with everything I got.”

On a balmy August afternoon, I meet Reed in an air-conditioned conference room in downtown Baton Rouge. He’s in Clubmaster glasses, a crisp white dress shirt and checkered blue tie, no jacket, wide blue pants, and nicely weathered brown wingtips. His head is shaved; his hands are thick and big. He walks with a slight hitch, or limp, which only adds to his general air of imposing grandness. As a young boy watching Uptown Saturday Night, he nicked the name of Calvin Lockhart’s nefarious gangster character, Silky Slim. Now, decades later, mostly everyone just calls him Silk.

The conference room is inside a spiffy radio station complex where Reed hosts a call-in talk show, the Stop the Killing Hour of Power, on Max 94.1. Well, usually he does: right now he’s on indefinite suspension for an impolite comment he made about the mayor, who has been criticized for the weakness of his response both to the killing of Alton Sterling and the massive flooding that has, in the last few weeks, made the city of Baton Rouge a precarious emergency zone.

It’s been a harrowing few weeks here. The death of Sterling was followed by the July 17 retributive killing of three police officers by a man from Kansas City (a fourth targeted cop, locals whisper gravely, is on life support). Then the flooding began on August 11, with a plodding, bizarrely heavy rainfall, not the concentrated fury of a storm surge but a slow and steady barrage. Thirteen people were killed; more than 60,000 homes may have been damaged. In some of the city’s parishes, more than 2 feet of rain fell in 48 hours. According to the National Weather Service, that’s the kind of flood that should happen once every thousand years.

“What’d you say about the mayor?” I ask.

“Oh, I said, ‘This goddamn mayor ain't shit,’” Reed recalls, laughing. “I said, ‘He hasn’t shown his face — but I bet you he somewhere showing his ass.”

Omnipresent around Reed’s neck are a pair of headphones, a thick rubber Bluetooth set that he can pop into his long, droopy ears whenever he wants, which is often. What he’s listening to, via his Samsung Galaxy, is the police scanner, and any possible incidents of violence that he’ll need to rush out and document. “I’m on it as much as I can,” Reed says. Practically speaking, that means he’s on it every waking spare moment. “While people sleeping, I’m up still, listening, drinking coffee. Some don’t like to see me, call me the death man. ‘Oh, he a buzzard. He always looking for something dead.’”

Hopping into Reed’s burgundy Buick SUV, we roll through his old neighborhood, The Bottom. Along with The Top and Cross Da Tracks, it makes up Baton Rouge’s economically depressed south side. (It’s also the home neighborhood of the rappers Lil Boosie and Kevin Gates.)

There are overgrown lawns and skinny trees jutting out onto the rooftops of modest, derelict wood-slat homes. Portable basketball hoops have their bases weighted down with tree trunks or loose chunks of cement. We drive by the New Jerusalem Baptist Church, the Islamic Complex, a diner with a handpainted sign endearingly promising a “Juicy Juicy hamburger,” and McKinley High, the first black high school in Louisiana.

Decades ago, Reed made his money in the dope houses in The Bottom. That’s where he first made use of a police scanner: back then, he used one to look out for narcotics-unit raids. He lived that life for 22 years, during which he was shot 12 times. Happily, he’ll let you pinch the clumps of skin in his back and his left knee where bullets are still lodged.

In 2001, while passing through Texas after a dope run in California, the car Reed was traveling in was hit by an 18-wheeler and spun off the road. He was the only passenger to walk away alive. Soon after, he decided to quit dealing. “I know how easy it is to open a door and unload a gun down the hallway,” Reed tells me, pantomiming the shooting of an automatic weapon, “and walk away and not see the aftermath. That’s why we show the funerals, the bodies in the streets.”

Pulling up on one bustling front lawn, Reed hops out and greets his dad, a similarly burly, similarly gentle man with a giant headwrap. One of Reed’s dad’s friends, identifying me as a reporter, cracks jokes: “Take my picture! Send me to New York!” A woman in a floral blouse pulls up the new Master P video on her phone: an ode to Alton Sterling, it contains bits of TV news footage of Reed. Grinning, Reed watches attentively.

Back in the car, Reed says that the atmosphere in the city is still “super edgy. Police don’t have remorse. They like, ‘OK, we have company here.’” By that he means the national news attention, which has lingered after the deaths of Sterling and Brad Garafola, Matthew Gerald, and Montrell Jackson, the three Baton Rouge police officers. “‘Wait till company leave…’ And we feel we way past that!” Quietly, we slip into the parking lot of the Triple S. “This is the spot where it happened at,” Reed says: the death of Sterling. It’s buzzing with shoppers, and before even getting out of the car Reed has bumped into someone he knows.

I fall into a quick conversation with Abdullah Muflahi, the skinny, soft-spoken owner of the shop. He himself shot a video of Sterling’s death, and released it soon after Stop the Killing’s footage. Shot from a different angle, Muflahi’s video better shows Sterling, prone and helpless, before his death. Afterward, Muflahi contends, Baton Rouge police arrested him without cause and illegally seized the store’s security-camera footage. He’s currently suing the department. “I’m doing OK,” he tells me. “I been alright. It’s calming down a little. I’ve been trying to deal with it. I’m recovering.”

A few feet away, on the outside wall of the Triple S, is a shrine to Sterling; in its center is a drawing of him, with his big-cheeked smile and his gold front teeth. “He was a goodhearted person. And he was troubled,” Reed tells me later. “But he wanted to live.”

Some minutes later, back on the freeway, Reed spots flashing police lights out of the corner of his eye. Spinning the Buick down the nearest exit then bombing it back up the side road, he gets us close to the action quickly. There’s an ambulance and a few cruisers creating a makeshift barricade. Reed whips with purpose around the corner of a barbershop, down another back alley, and through a breach in the cruiser barricade. “What is that?” he says. “I seen a body on the floor?” Closer to the action, we note a banged-up tourist bus, and nothing else. It’s a car accident. False alarm.

The most famous document in the history of American copwatching is the brutal beating of Rodney King. Shot by a truck driver named George Holliday from his nearby apartment balcony on March 3, 1991, to this day it feels like a bizarre bit of samizdat, as if it were a reality to which we are not meant to be privy. It’s also a dramatic outlier.

Holliday’s tape reverberated through the world. The experiences of most copwatchers, however, are more in line with that of Mario Vara, a Cuban-American who lived in Rochester, New York, before passing away in 1993. Vara took up the practice after a violent confrontation in 1986 in which Rochester police busted into his family’s home, smashing it up in the process of searching for a gun that the family did not possess. Vara’s son Davy recalls his young brother telling one of the cops, a man nicknamed Rambo, that the warrantless search was “unconstitutional.” The cop, laughing, shot back: “Who are you, Perry Mason?”

In the years after, Mario Vara effectively became an amateur documentarian, diligently trudging out on the streets of Rochester with a bulky Panasonic OmniMovie VHS camera to record traffic stops and arrests. “‘Man on the corner,’ he used to call it,” Davy says, explaining that his father believed that the only way to keep city officials honest was to keep an eye on them. “He used to say, ‘Rights are not asked for, rights are not given — rights are fought for each day.’” Seeing as he was active at the advent of home-recording technology, he’s something like an unsung pioneer of the field. And the very fact that Vara is a marginal figure in the history of copwatching is precisely what makes him far more representative than George Holliday or Arthur Reed: overwhelmingly, the practice of copwatching is a non-impactful pursuit, practiced in solitary anonymity.

“These people, when most would flee, they’re rolling. With Eric Garner, most people would get out of there as fast as they could. Ramsey Orta’s like, ‘Nope. Just gonna stand here and film this whole thing.’”

There is a thread between all copwatchers, whether their footage results in action or not: their acts of witnessing are kind, and they are brave. Michael Kamber is a now-retired combat photographer who’s shot for the New York Times in war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan. “These people, when most would flee, they’re rolling,” Kamber tells me of the witnesses of police killings. “With Eric Garner, most people would get out of there as fast as they could. [Ramsey Orta’s] like, ‘Nope. Just gonna stand here and film this whole thing.’ It’s pretty amazing.”

Soon after the August 2014 police killing of Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, a local man named David Whitt began copwatching locally. Eventually, with aid from the national organization WeCopwatch, Whitt formed an organization called The Canfield Watchmen, named in part for the street on which Brown was killed. Since, Whitt has traveled to Baltimore and North Charleston, South Carolina, where Walter Scott was killed, to introduce local activists to copwatching. Currently, The Canfield Watchmen are in the process of renovating a Missouri house, bought with funds from an anonymous donor, and converting it into a full-time educational center where budding copwatchers can learn best practices.

WeCopwatch has also pulled Ramsey Orta and Baltimore’s Kevin Moore into its orbit: both are advocates with the organization. They’re also now pals: Moore was with Orta at the latter’s July plea deal hearing in Manhattan.

Orta has expressed regrets over not releasing the Eric Garner video anonymously, and sparing himself the commensurate police attention. But he’s proud of what he did. “What I saw that day was the NYPD murder my friend,” Orta told Democracy Now. Asked if he’ll continue copwatching, Orta responded, “Yeah. I’mma keep filming.”

Sandra Sterling

Sandra Sterling

Sandra Sterling, Alton Sterling’s aunt and the woman who raised him after the death of his mother, stands in the fading dusk light outside her single-story ranch home in Baton Rouge. She’s in socks and jeans. As we stand around, she swats away the bugs attracted to the bare light bulb above us. “I’m gooooood,” she says wearily. And then, more assuredly — her smile, like Alton’s, showing a few gold front teeth — she adds: “I talked to the president today.” President Obama, in town briefly to give Baton Rouge a boost after the flooding, made sure to pull Sterling into a private room at the airport before he left.

With evident pride, Sterling recalls the comfort that the meeting provided. “Oh man, he’s the coolest,” she says. “It was just like talking to a regular person. He said he visited the city, and he said that I did a good job of keeping the peace, and that I was a phenomenal woman. I showed him a chain that Vice President Joe Biden gave me and he said, ‘Oh I’m gon’ top that. Just watch your mail!’ And he told me about Alton. He said, ‘I’m not gon’ forget about Alton.’ He said, ‘I’m never letting this go.’”

A few days prior, Sterling traveled to Houston to meet with Mike Brown’s mother, Lesley McSpadden. Since, the two have been texting regularly. “She said she didn’t get justice for her son” — Darren Wilson, the Ferguson cop that killed Mike Brown, was not indicted — “but she still fighting,” Sterling explains. “And she is not talking about the money at all. I said, ‘It’s the same thing for me.’” Sterling is not concerned with a potential civil suit settlement, she says, because as the operator of a bail-bond agency, she supports herself independently.

It was Reed that connected Sterling with McSpadden; he’s become something of a networker for mothers who have lost children to police violence. He tells me of their distinctive personalities: the aggressiveness of McSpadden, the public polish of Trayvon Martin’s mother Sybrina Fulton, the quiet determination of Tamir Rice’s mother, Samaria Rice.

“And what I can say is, each one of these mothers are one step away from losing it,” Reed attests. “Sybrina says when she woke up and looked at what had happened to Mike Brown, it turned back to the day she found out about her own son.” Every police killing feels like “a repeat and reliving.”

As the three of us spoke, Sterling’s attention is primarily focused on the immediate concern of flood-relief efforts. “I was out there giving water and food to the community,” she says, “and then I went to talk to the president and guess what I did after I left the president? Went baaack to the streets giving water and showin’ em love!” The response was reciprocated: Sterling was repeatedly comforted by flood victims. “People, when they realized who I was, they hugged me and said, ‘I’m so sorry for Alton.’”

In one small way, the tragedy of the flood has given Sterling a much-needed purpose and focus. Later, Reed would explain to me how important he believes it is to keep mothers who have lost children focused on a fight or a task; otherwise, the drift to desperation can happen quickly. And indeed, in the immediate aftermath, Sterling recalls falling into a haze that lasted days.

After joining the protests that sprung up around the Triple S in response to Alton’s killing, Sterling lashed out in anger at friends for not joining as well. “I’m asking them, ‘Where was you? Why you ain’t come out here?!’” Many of those friends, it turns out, were in fact right there next to her.

“I had to show her pictures of us,” Reed interjects, smiling.

“They actually had to show me pictures,” Sterling says, nodding. “And they was out there the whole time.”

Looking ahead, Sterling braces herself for legal disappointments, but is resolute: she believes there will be a path for justice, even if it’s not in the courts. She believes the story of Alton’s killing needs to be told, and learned from; she believes it has power. She tells us of a police officer, a white man who embraced her after her meeting with Obama at the airport.

“I’m trying to shake his hand,” Sterling says, “and he grabbed me and held me and he was crying. And I said, ‘You gonna make me start crying. You gonna make me mess my makeup!’ And this man, he was crying and crying, and he said, ‘I saw the video.’”

“Everybody saw the video,” she adds. “So they might wanna do the right thing.”

The sun has set in Baton Rouge, and the power has been out in some homes for weeks, but there’s still enough moon and street light to see. Reed is piloting his Buick slowly through residential neighborhood after residential neighborhood, making sure I note the damage of the flood. It’s impossible to miss: every house on the street now faces a massive cluster of trash. At some stretches the clumps run 60 feet long uninterrupted along the curbs, maybe 15 feet high. The trash clusters are made up of every last stick of property that was once inside the homes.

Stacks of mattresses, stacks of chairs, cribs full of toys, washers, dryers, stoves, pianos, wicker baskets, pillows, children’s trophies, dressers, piles and piles of crumbling cardboard and closet doors and drywall and the basic materials that the houses are made out of. The insides of homes, ruined, clumped up, and tossed aside. Heaping piles everywhere, arranged as neatly as possible, their strange shards jutting in all directions. The phrase, appropriately, is that the homes have been “gutted.”

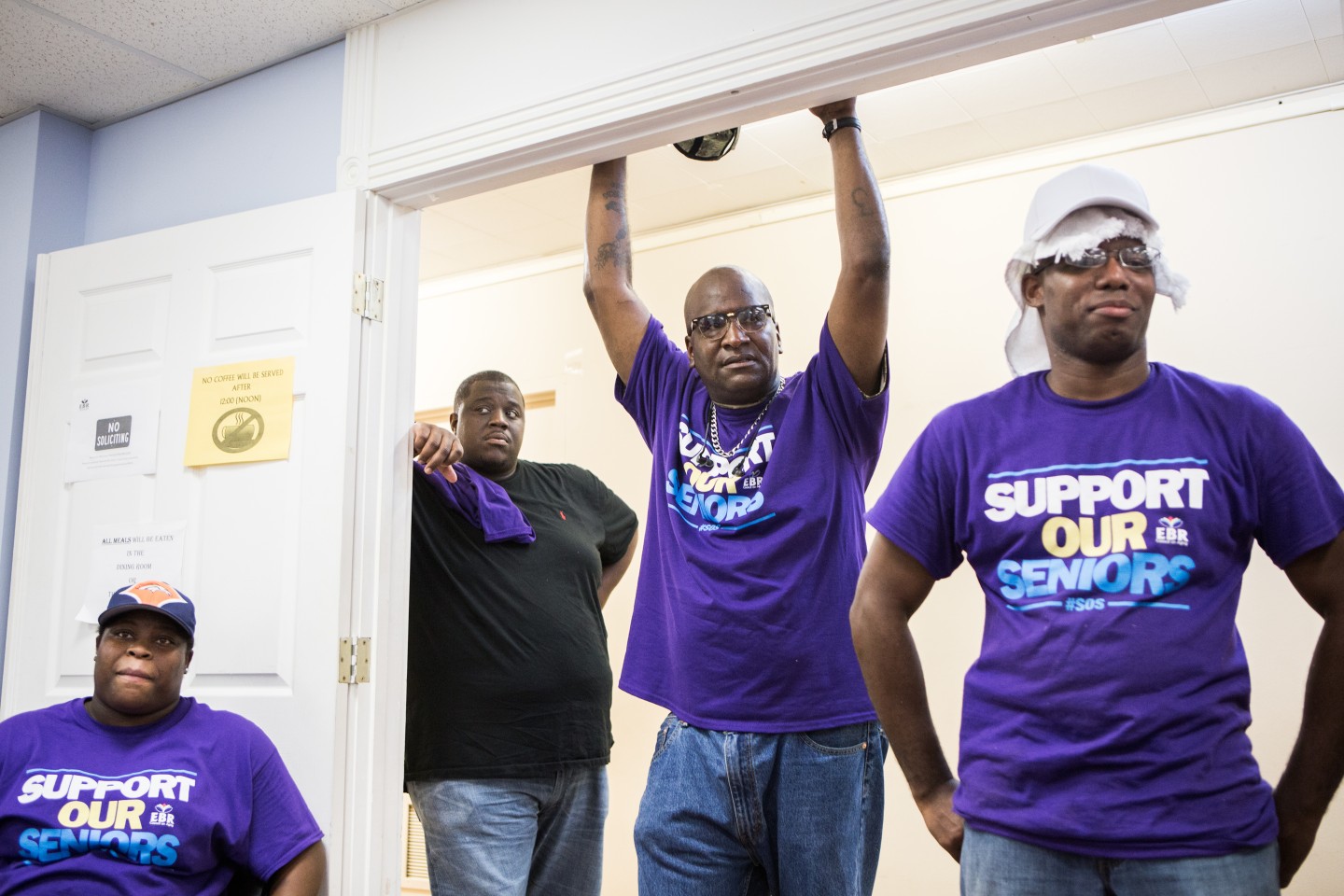

Some residents of Baton Rouge, looking back at the tragedy of the last few weeks, have found solace in the response to the flooding. They’d like to believe that Sandra Sterling’s flood-relief experience is emblematic of something grander: everyone together, pitching in. Earlier in the day a young man named Keek, a Stop the Killing volunteer, pulled up local news footage for me on his phone. “You saw the Cajuns on the boat saving people? Look at the racial diversity on the boat! You got an Asian lady, white people, maybe Hispanics — they were saving white people and black people!”

Reed, too, sees a net positive in the aftermath of the flooding. But his view feels more ominous: he believes that the flooding has cut the tension, distracted from the killings of Alton Sterling and the police officers; he believes that if it wasn’t for the flooding, more killings may have occurred.

In the car, I ask what would make him feel that Stop the Killing’s effort has been worthwhile. Perhaps an indictment of a cop who — “A conviction! A conviction!,” he shouts, cutting in. “Even if it’s just one! If just one get convicted! ‘Cause then the next one knows there’s a chance his ass could stand trial, too.”

There’s an hour or so go to before the city’s post-flooding midnight curfew, but already restaurants are shacking up and sending their employees home. We roll past a Lebanese spot and a strip mall gone dark before finally finding a burger counter open. There, Reed flashes back to surviving that fatal car accident in Texas.

Soon after, he recalls, he went lake fishing and caught a “little bitty poach fish.” Feeling suddenly sensitive about death, he immediately released it back into the lake and prayed for it to live. Reed waited and waited to see the thing pop back up, breathing. He waited some more. Finally a big white bird flew down, swooped up the fish, and flew away.

Over our burgers and XL fountain sodas, Reed says of today, “It’s a good thing: we can say we didn’t record any murders.”