When my mother and I fight we both revert to the obscure South Indian language she was raised to speak. Malayalam puts me at a disadvantage; I know it almost as well as English, but it offers her a better quality of insult. “Daughter of a criminal sentenced to hang” has less of a bite in translation. And to be crass in the language of William Wordsworth is, to my Mum, a betrayal of the Commonwealth. I have not told her that to be crude and ungrammatical would buy her the ease and assimilation she has spent decades chasing. In the current state of British life, which is so distrustful of the economic migrant, I wonder how her sense of acceptance hasn’t dimmed.

Brits like hierarchies, or at least those at the top of them, winners of a lottery of birth. We are generally affectionate towards the royals, ignore much of aristocracy and forgot the recent indiscretions of the city’s bankers. But the immigrant is visible. The immigrant is suspicious for her lack of belonging. The immigrant in this system comes last. Especially visible is the migrant Muslim woman, a tribe that peppers my own family. The oft-acknowledged, never-solved issue of patriarchy has left these women open to accusations from politicians, from our own former Prime Minister even, that they are traditionally submissive or are oppressed by their own thinking. Worst of all, it has been said, they don’t appear to integrate, forming a culture where the immigrant and white populations live strictly and willingly apart. The occasional local figure or commentator will label these communities “ghettos.” Sometimes difficult, needed debate can be undone by a thoughtless word.

The word “ghetto” has such a history. Every connotation is tinged with race. Today the word is shorthand for a part of a city where one minority or, like in my South London hometown of Croydon, a few, dominate. Received wisdom holds that this prevents community integration within white society, though that’s probably not considered by the newly arrived immigrant. Regardless, this is portrayed as life at the bottom of the social ladder. A glance at many a Brexit poster will tell you so.

In the spirit of all good clichés, I hated my hometown. I resented the proximity of so many aunties and uncles of no biological sort. I was annoyed by the loud music, artists like Nas and Jay Z , that I wasn’t allowed to listen to but that my neighbors and school mates shared through thin house walls and playground bragging. And I saw the numerous chicken and chip shops as calorific taunts, a sure sign of the impending apocalypse.

In defense of that 14-year-old girl, I was trained, above all else, to get out. An early obsession was the idea of suburbia, normally the realm of the thirtysomething: a clean lawn and rooms for every child in the house. Good grades, the easiest route to away, were maintained. But my Mum wanted more. Embarrassed by the remnants of an Indian accent, by the way she sometimes stumbled in front of my teachers, she wanted her children’s speech to be colorless. No person, hearing their voices on the phone, should be able to detect the presence of a foreigner’s womb.

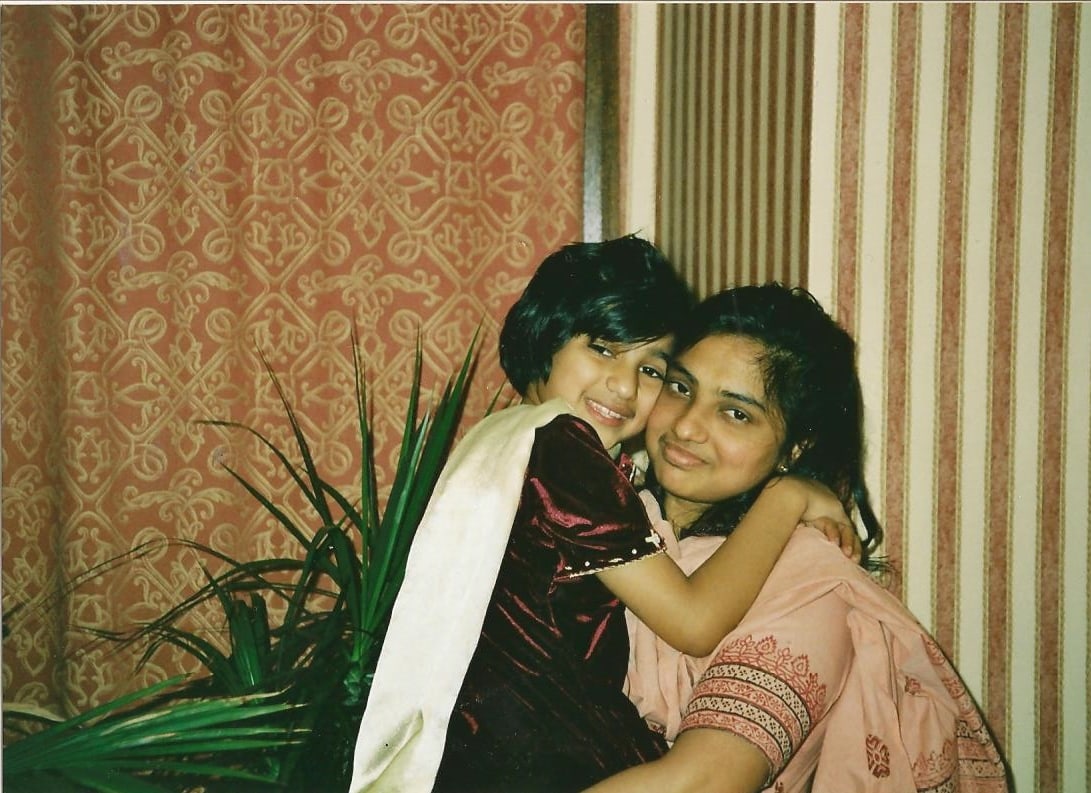

The author with her mother in 2000.

The author with her mother in 2000.

The hierarchy of migrants involves race and class, but it’s really about words. Or rather, about the fact that we’re most comfortable with the people who can do more than simply communicate with us.

Hindsight informs me that this was madness, but I still remember what were essentially elocution lessons as being great fun. No 8 year old can resist a tongue twister. The South London accent is at its best on screen when you watch John Boyega in Attack the Block. If you haven’t seen it, imagine hard Ts, much kissing of the teeth, and frequent abbreviations. This speech of mine was pared down to something more generic. I no longer obsess over class but that voice I lost permanently. There was one upside: the compelled performance brought with it a totally unearned confidence in using language. Muslim woman and migrant child I may well be, but no one would query my integration. I talked, someone once said in praise, like I was white.

The hierarchy of migrants involves race and class, but it’s really about words. Or rather, about the fact that we’re most comfortable with the people who can do more than simply communicate with us. Languages allow room for humor, empathy, and dry asides to be slid into a short riff. They require confidence and don’t much care for textbook learning. English spoken without visible effort is preferable to the careful sort, which is still better than when it emerges devastatingly broken. Fair enough. But settling in, assimilating without losing yourself, requires a bit of support. It requires a semblance of familiarity, even thousands of miles away from home. The presumed ghetto has a purpose.

When I moved from London to a university town, I told half truths about my upbringing. I deployed those constructed plosives to buy assimilation. And yet I still said my prayers in Arabic. Perhaps the latter triggered my homesickness. It wasn’t a particularly long bout but it was intense and absurd. I missed the food, the gallows humor and even the gossip of home. One new friend made the mistake of convincing me to play some late-90s hip-hop, increasing my melancholy. It sounded like home, like a neighbor blasting music from the other side of my bedroom wall. Then I started chatting with the people of color I saw daily out in the city, though none were fellow students. A young woman who worked in a corner shop and a middle-aged Turkish man who sold me chips at questionable hours, became allies that I could crack particular jokes with. I didn’t have an epiphany or fill a spiritual vacancy. But with enough distance, came a bit of insight.

There is so much worry in the U.K. today about the wave of immigrants coming into the country. This deserves to be heard. But I can’t blame families like my own for building communities like the one I miss. I can understand the need to lapse back into Urdu in the beauty parlor. I can sense the delight of reading your horoscope in the Tamilian magazines. I know what it is to yearn.

Occasionally my friends are bemused as to why the shy figure I introduce falls short of the matriarch in my anecdotes. I don’t know how to explain that said woman has been wandering around the kitchen all week in preparation for meeting them, rehearsing possible conversations. I don’t know how to explain that her Indian ways often embarrass my assimilated, English self.

My folks eventually left for the suburbs they once imagined but kept in touch with the old bit of town, the way you do with family. Most of the people we know there voted to leave the European Union. They are once-upon-a-time economic migrants who worry about jobs and housing and a new wave of immigration. They speak clear English. I present them with liberal arts arguments against Brexit but end up using buzzwords like “cosmopolitan” and “globalization.” Worthy words, used so often, so publicly and earnestly by politicians here that they have become useless in meaning. My old neighbors are proud of exiting the EU. Their arguments are as infused with patriotism as my own. I disagree with them on just about everything. But I also see them as most things a successful migrant ought to be: proud grafters, unconcerned with all possible rankings, British. Brexit has pitched the notion of the cosmopolitan and globalized against the patriotic and communal. But I’d wager that places such as the urban melting pots I grew up in, where the imperfection of speech bests judged articulacy, show the joys of English pluralism.

“I just want them to understand me,” Mum will say about meeting my friends. “I think my accent is getting a bit softer though. But what if it is fast? You all speak so fast these days.” Always, I laugh her fears off, knowing her to be paranoid and my friends to be an embracing sort. I cannot comprehend the instinctive discomfort of permanently living in a language that is not your own, the mastery of which proves your worth. That is the gift I have been given. But if I were emigrating today, I’d want to pick a city where a South Asian beautician can be found to deal with my eyebrows. And if there’s a chicken and chip shop next door, so be it.