Andrew H. Walker

/

Getty Images

Andrew H. Walker

/

Getty Images

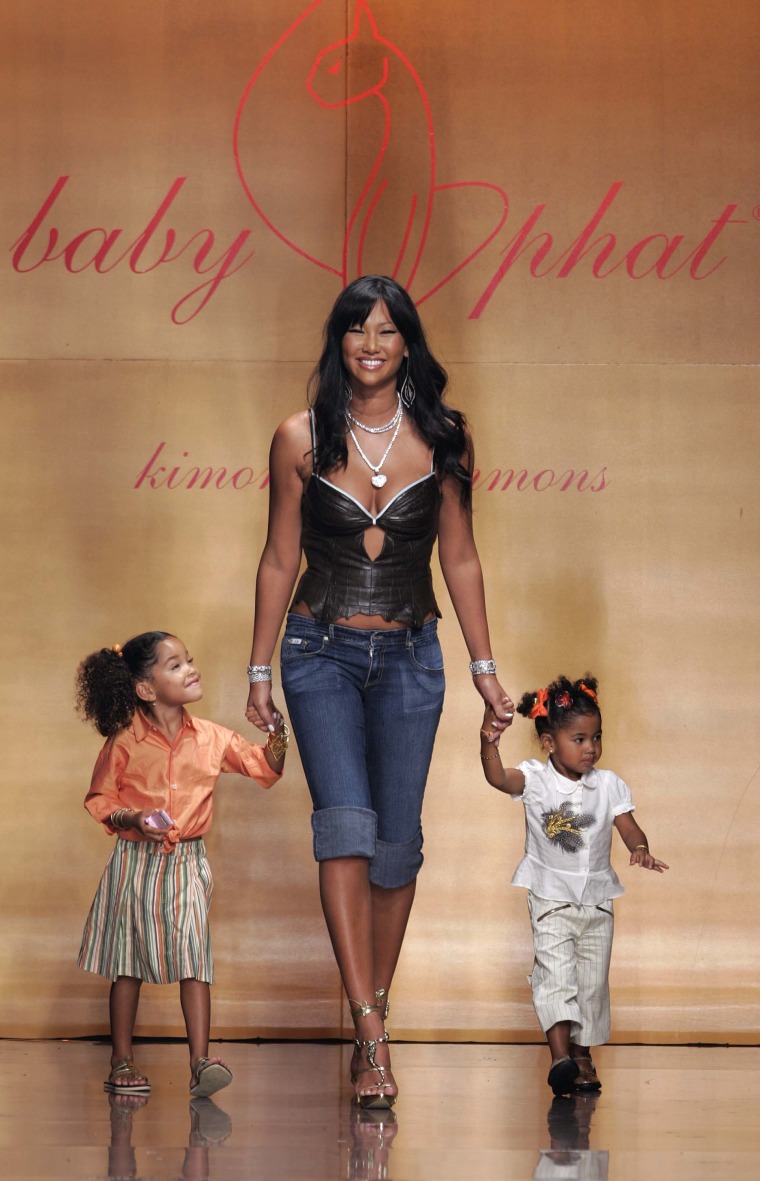

In the late 1990s, hip-hop crossed over into popular, mainstream culture, bringing with it the idiosyncrasies of the communities that birthed it. For years, rappers and their peers were known to improvise, buying jeans from legacy labels like Polo a couple of sizes up to create a baggy silhouette and turning non-fashion brands like Timberland into wardrobe staples. But by the late ‘90s, instead of continuing to promote established brands, rappers and hip-hop industry influencers began creating their own platforms and launching black-owned clothing labels such as FUBU, Pelle Pelle, and Rocawear. In 1999, supermodel and clothing designer Kimora Lee Simmons started Baby Phat, a clothing, shoes, and accessory line designed for women and girls at a time when similar brands were geared towards men. It was built alongside Phat Farm, the line owned by her then-husband Russell Simmons, whose renown as a hip-hop executive also positioned Simmons close to the hip-hop community. Soon, Baby Phat became a billion-dollar enterprise.

Baby Phat cultivated and sold an aesthetic that was both accessible and ambitious. When rap icon Lil Kim modeled for the brand in 2008, she hit the runway in a long fur coat over a cropped white tank, bikini bottoms, and a massive diamond cross chain. It mirrored the celebration of black culture in many of Simmons’s designs, a quality that led traditional fashion institutions to label Baby Phat as an “urban” brand that wasn’t supposed to penetrate high-end fashion spaces.

In 2016, the overt embrace of “fabulousity” that Baby Phat was once shut out for is channeled in some of contemporary, mainstream fashion’s current trends. Runways are styled in appropriated looks like oversized logos, faux furs, and embroidered denim reminiscent of Simmons’s designs from 17 years ago. In his 2014 Fall/Winter Paris fashion show, Rick Owens dressed white models in du-rags, and at this year’s New York Fashion Week Alexander Wang showcased airbrushed t-shirts; both styles have been ubiquitous in black communities around the country for decades. In such instances, these looks are presented as innovative and no acknowledgment is given the black culture responsible for creating the pre-existing trends or to the black designers who were stigmatized for bringing that culture to their designs.

In September, The FADER spoke with Simmons to talk about what it was like to innovate women’s fashion, the racial undertones of being labeled as “urban,” and the credit that is due to black culture.

When you created Baby Phat, what was your vision for it?

When I created Baby Phat, it was something that was very authentic to me. In that respect I feel that I am a pioneer because there were not a lot of women what I was doing at that time. I didn’t want to wear a football jersey from a man. That was not what I wanted in the sense that it was like your boyfriend’s clothes, like his jerseys. If anything, I would’ve made a sporty-looking jersey that was much smaller and more tailored and that’s why we created what everyone called the “baby tee.” At the time, there were a lot of men doing these things. You can speak with Russell [Simmons] or Puffy, but no one was doing it like we were doing it. We were speaking to the women. At that time [our customer] was a young woman and she wanted to feel sexy. We were crossing over to be more feminine and fitted and sensual. Not only did I bring a history of where I came from but also things that I’d seen and where I’d started and for me that was high fashion.

So, for Baby Phat, a result of that combination was a great fitted jean. They were super stretchy, I had the best jeans in the world. It was a denim company with little t-shirts, and dresses. The way that it was done and how we did our color blocking was different. It was offering something towards women.

A lot of the looks that you introduced with Baby Phat were marginalized in the late 90s and early 2000s and it was implied that they were limited to an “urban” community. Now, we see women who wouldn’t be considered a part of that demographic dress this way and it’s no longer labeled as “urban.”

And I was certainly embracing my history and where I’d come from, in coming off of the fashion runway and in the physical sense of where I was from in St. Louis, Missouri. There was nothing weird about that, certainly not as far as the fashion was concerned. The weird came from New York City streets, and Paris. It was homegrown [from all the different cities I’d spent time in].

I was paying homage to the feminine form, body, and shape and the references that I was using, the materials, the finishings, the metals and so on and so forth. The sizes of the logo, the placement of the logo — they were really big and they’re looking really big nowadays, too. Who would’ve thought ever that Ralph Lauren would have a logo on the chest that is the size of the palm of your hand? There was a time that someone would’ve mistakenly called that “ghetto.” But, that at the time would’ve been a negative connotation. So all I’m saying is, to me, whatever it is [labeled] is not negative. Even though you may have seen that in the ghetto you never would’ve said, “Oh, Ralph Lauren is ghetto.” Even now, for these other brands that are higher end, the logos are huge and so are the sizes of the zippers, the earrings, and the stitch. I call it “retro” but what I was doing back then was something that was true to myself because that’s where I was from.

I didn’t want to be called “urban” because I didn’t understand what made me urban and, let’s say, Tommy Hilfiger not. Now, people in fashion might call it that but they would not have said it then. To me, it was only called that because of the color of the people working there and I thought that was some real racist shit. So back then, I was fighting the fight because I wanted to be included — it was fashion.

You’ll see braids on some celebrity and it’s like, ‘Oh, they started that trend.’ No, they really didn’t.

Carlo Allegri

/

Getty Images

Carlo Allegri

/

Getty Images

In the beginning, Baby Phat was a brand that many young black and brown girls could see themselves in. It represented our culture and style. We could still afford it and feel glamorous, too.

I always strived to represent my audience. Back then, I called Baby Phat “aspirational” because you could mix the high luxury with everyday streetwear but still, fashion is about that aspiration. It was living a dream. It was the American Dream, and that was who we represented and that was my customer. We were the American Dream. People may have tried to take us out of that, [but] we were nonetheless American.

How would you say that Baby Phat was received by traditional fashion institutions at the time?

I built Baby Phat to be a billion dollar brand. There was a time that I had probably 50 licenses that made everything from baby clothes to lunch boxes to color cosmetics, headphones, fragrances, you name it — it was huge. I always used to ask myself, What makes somebody successful? To me, numbers are success. People that you inspire is success. We had all of those things but there were definitely a lot of times that people didn’t want to let me in. When I’m talking “people,” I’m talking mainstream and high-end fashion. They didn’t always want to embrace me or consider me and I’d say, “Wow, I sold more than you. With my eyes closed.”

Why do you think that fashion was so hesitant to accept it?

Maybe Baby Phat was different or maybe it wasn’t so different. In a lot cases, they were trying to emulate it. Maybe it was the audience that I reflected or represented. For example, a big thing that we made big was the down puffer jackets with the fur around the hood. We pushed that jacket until it was at the MET Ball on the red carpet [worn] on the outside of a gown and then, sure enough, Moncler did it. We weren’t the first ones to make a ski jacket because, of course people, have been skiing for a hundred years but we were the first ones to make that fashion. Then, sure enough, it was being worn over Ralph Lauren and Donna Karen. So, they definitely emulated it. It is said that imitation is a high form of flattery so, if you look at it in that way, that’s what they were doing. Other people would say they were stealing.

How do you feel when you see other brands emulating a culture fashion didn’t want to fully accept before?

They’re inspired by something that we already knew and it’s also homage to vintage fashion, because what goes around comes around. Depending on who you’re talking about you may say, “Hey, you can’t do that. That’s not authentic to you.” But I was one of the creators and pioneers of it and it’s authentic to me —it may not be to everyone else who’s using it. I see it in the stores, ads, and the blogs. Maybe they call it American fashion but at the time it was “ghetto fabulous,” it was ”urban,” it was “hip-hop culture,” it was “streetwear.”

It was all of those things that they used to pigeonhole us when really we just wanted to be a part of the bigger conversation and sit at the bigger table. I guess when it works for them, they use it and are inspired by it but it boxes you in. And I was thinking outside of the box. I didn’t know how to go in a box. My mom is Asian. I didn’t go in a box. What box?

Do you feel like you received the proper credit for what you pioneered in hip-hop and fashion culture?

If I think about it in that way, maybe not. But I don’t ever look at things to get the credit because if so then there were all lot of things that didn’t get credit along the way. I know what it was and what my part was in the culture and in the upbringing of young ladies at that time. I often say [that] for fashion week, we were the first brand to broadcast live on a jumbotron in Times Square. A lot of people did it after that. I was the first designer in history to have a fashion show at Radio City Music Hall and others have done that since then. I was one of the first to put my kids in ads.

The reason I did that is because they were my mini-me’s and we were showing a lifestyle. I wasn’t afraid to show that I have a family and certain luxuries that I love. It was aspirational and certainly my customers were aspiring to be like me. They were aspiring to have the Franck Muller watch and if they couldn’t have that, they could have this Baby Phat jean because I wore my watch with that jean. It was a mixture of everything. It was actually the retailers that I think had a lot of success exploiting the market. Those big names and brands reversed with logo-driven goods and were replaced with proper streetwear they were pushing to be more “urban.” I feel the retailers really milked it to the last drop but that ushered in the death of urban sportswear. What you see now is that the trends that drove them are still alive and well. That’s the speed of contemporary and designer fashion.

In Milan, Philipp Plein had a 2017 Spring/Summer show called “Alice in Ghettoland.” It had fashion looks, big rope chains, logo sneakers, and all of that. It’s funny because my last show for my Kimora Lee Simmons line, which is designer-level, was Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz because I’m from Missouri. It rings true all the time. I didn’t have to pick, The Wiz because there was a wizard that was for everybody and all the colors. Bring Toto too. If I did “Alice in Ghettoland” then or now I would’ve called it “Alice in Wonderland” or it would’ve been “Kimora’s Dreamland.” I wouldn’t have said “Ghettoland.”

You didn’t have to. When you look back, even the way you paired furs with silks and prints has come back around.

Yeah, I feel l like they never would authentically credit “urban” streetwear or certainly never credit black culture or minority culture for these trends. Now, they’re doing the baggy silhouettes, the layering of pieces, all of the Afrocentric hairstyles like a real afro. Now you’re seeing it on the runway. You’ll see dreads, big braids, and on and on with the make-up trends. You’ll see braids on some celebrity and it’s like, “Oh, they started that trend.” No, they really didn’t.

It’s very important to keep the dialogue about this alive. It’s not going anywhere. It may change how it looks and what it takes to do so but you’ll never be able to steal that beauty, those ideals and where those things came from. No one will ever be able to steal that. How far will you go to be able to get away with that? You won’t be able to get away with that. That’s within us. You can check it time and time again and it’s ours. So yes, a little credit is due.