How To Successfully Fight For Change, According To 6 People Who Actually Know

Tools for effective organizing from a former Black Panther, a pioneering abortion rights activist, and more.

“Revolution,” the poet and singer Gil Scott-Heron once said, “sounds like something that happens, like turning on the light switch, but actually it’s moving a large obstacle, and a lot of folks’ efforts to push it in one direction or the other have to combine.” The obstacles in front of us today seem as towering and as insurmountable as ever: immigration rights, gender equality, class injustice, state-sanctioned police terror, Donald Trump. Perhaps at no point in history have our freedoms been more under attack than at this decisive juncture.

As such, small and large revolutions have sprouted in response to Trump’s presidency, and all that it threatens to bring: legislation that will defund Planned Parenthood, a rise in Islamophobia, emboldened white nationalism, and the end of healthcare for tens of millions of Americans. And yet hope remains — thanks in large measure to a dedicated core who have continually put in work. Still, there are dark days ahead, so The FADER reached out to veteran activists across varying social, political, and religious movements with one key question in mind: How do you keep fighting?

Eleanor Smeal, 77

Former president of the National Organization for Women (1977-1987), leader of the first march for abortion rights, coined the term “gender gap,” current president of Feminist Majority Foundation, publisher of Ms. magazine.

I became chair of the board of NOW in ‘75, and was president from 1977 to 1982. I ran for reelection in 1985, because I was concerned about losing Title IX, which was essentially gutted. We had to reinstate it right away because if we didn’t, we’d lose a generation of young women’s college opportunities. At the same time, violence toward [abortion] clinics had started. Because Reagan was president, we were worried that the court would be stacked and Roe v. Wade would be reversed. I said, “We just gotta have a march on abortion and reproductive rights.” We were told women wouldn’t march because they’d be embarrassed. We thought that was ridiculous. 125,000 women marched for abortion rights in Washington, which, in those days, was a big number. That was just the beginning.

When we started, to make a flyer you had to use a printing press. We had membership lists on addressographs. Even now, with all this technology, the most important thing is face-to-face meeting. Mass rallies and marches are imperative — nothing replaces that kind of energy. Coalitions are very important. You don’t forget conferences and meetings, and I’m not talking just national, but at the local level. The duty of a movement is to communicate in every way you can think of. You have to make sure your people are so informed that each is a leader. Don’t get discouraged or let small things aggravate you. A positive attitude — that your voices will be heard — is imperative. Young, old, whatever your race, we’re all together on the face of this earth for a very short time. You gotta walk shoulder-to-shoulder forward. No going back.

El-Farouk Khaki, 53

Co-founder and coordinating Imam of Masjid el-Tawhid (Toronto Unity Mosque), founder of Salaam, a support group for gay Muslims, refugee and immigration lawyer.

When I moved to Toronto in 1989, I started to meet other people who were Muslim or Muslim-identified and members of the LGBTQ community for the first time. And yet, we were not connected as Muslims, or as queers within the Muslim community. I started to think, “Hmm, it would be nice to have a place where we could all get together, where we don’t have to explain ourselves. Where we can just be.”

I refer to myself as “the accidental activist.” A large part of my activism comes from my own need to have inclusive and accepting spaces. Those times that I have not been able to find these spaces, I have had the privilege, the social advantages, and the networks to try to create those spaces. My biggest lesson has been patience, from my Sufi path. Even when things don’t go the way you want, there is still progression. For example, one of my friends who never came to Salaam recently told me that just knowing there is a queer Muslim organization had a positive impact. Even if people are not flocking to you right now, the work you do can have an impact on people who are not physically showing up.

I keep going because I’m not alone, I’m not indispensable, and we’re in this for the long haul. Our struggle to transform the world is a long one, which means we can practice self-care, step back, or say no. Integral to our activism is our own transformation as agents of social change. We cannot change the world till we change hearts, and we cannot change the hearts of others until our own hearts are transformed.

Protestors take part in a demonstration in 1977 in New York demanding safe and legal abortions for all women.

Peter Keegan/Stringer/Getty

Protestors take part in a demonstration in 1977 in New York demanding safe and legal abortions for all women.

Peter Keegan/Stringer/Getty

Peter Kennard, 67

Photomontage artist, Senior Research Reader at the Royal College of Art, famously produced imagery for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

When I was training as a painter in the ‘60s, I realized what was happening around the world — all the demonstrations against the Vietnam War, and the invasion of Czechoslovakia [by] Soviet tanks. I wanted to find a way to relate through my art, rather than having a separation between art and my political beliefs. That’s why I started using photography, because it takes [the viewer] back to reality rather than the idea of art. [In a photomontage], you have two images, and you put them together and create a third meaning, and unveil some of the lies that go on in everyday discourse. So you put together, you know, an image of the Prime Minister with an image of the destruction that they're causing. Usually the powerful are separated from the results of their actions.

I’ve always believed that for artists making work about politics, it’s no good just talking to the art world. They're not the people who are going to change anything. Make images that are very clear, that people can get straight away, and then put them on everything from exhibitions in galleries to t-shirts to badges. Art isn’t mysterious. You’ve just got to make work that you feel passionate about, and then find a way to get it into the public realm. It’s very good to work collaboratively, especially for young artists now — it’s so difficult, economically, that you’ve got to work in collaboration and not worry about the big deal 'art world.' That’s not important, that’s another world. Now we’ve got complete horror and madness going on; it’s really important to get these dissident, critical images out there.

Suzanne Elder, 56

Community organizer for healthy adolescents in Chicago, senior director of State Health Systems for American Cancer Society.

I got into organizing completely inadvertently. It was 2006. That was the year that my work in health policy shifted from a strictly professional realm to a painful and personal one. My daughter was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes and we learned first-hand how and why schools were turning their backs on children with diabetes and other chronic health conditions and what this meant to their health, safety, and education. I started out my career in health first in advertising and later made the change to health policy. I began to see the political structures in my community failing in terms of representation, and quality of policies and programming. I sensed that [children and adolescent health] was never really a priority for policy and law makers because as a constituency children really just don’t have a lot of political power. So I coordinated and championed legislation for kids with disabilities, and organized young people to develop programming around sexual health and sexual health education. It was about finding ways to tilt the scales so the voices and needs of children’s health care were heard and appropriately incorporated into an agenda. I wish I could tell you it was full of planning and foresight and lots of smarts, but it was highly reactive: a little bit of mad mommy, combined with someone who just happened to have a background in health policy.

The best and most important contribution I made as a facilitator/convener/organizer is basically pulling the adults back. Years ago, New York City developed a condom availability program that is honestly some of the smartest public health work you’ll ever see. But Chicago didn’t have relationships with super high-profile product designers or a budget either. Yet we were still compelled to solve the problem of making condoms available to adolescents and young adults. So we put them in charge to design the intervention, and think through the social issues and barriers to implementation. Young student designers from Columbia College designed condom dispensers that are now in half, if not more, of Chicago public high schools. It was a solution designed by students for students, and is a wonderful example of what happens when you trust young people to recognize and solve the problems in their own community and lives.

Collaboration is as powerful a tool as a conflict-oriented approach: it really makes a place at the table for everyone to be authors, activists, and points of inspiration.

Penny Rimbaud, 73

Co-founder of seminal anarcho-punk band Crass, co-founder of Stonehenge Free Festival, performance artist, writer.

From as early as I can remember, I didn't like the picture of the world I was told I was going to have to live in. It had to be better than this. Over my life I've tried to look at more positive and sustainable ways of existing, and sharing that with people. Whether that's running an open house, or forming a band like Crass, or organizing Stonehenge Free Festival.

Peace symbols [were] very big in the ‘60s, but disappeared by ‘77. So I went up to the CND [Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament] offices with [Crass singer] Eve, took some badges and gave them some money, and then we started putting up the peace sign [at] gigs. We managed to revitalize the Peace Movement. The Peace Movement [was a] pretty exclusively middle class preoccupation in the mid-’70s. We introduced it to working class kids. We became much more emboldened. Okay, the band's an information service, we can tell people what things are happening and when they're happening as a sort of recruitment agency for the direct action movement. That led to more on-the-street gigs, like Stop The City, which we were very much a part of organizing. Out of that came things like Reclaim The Streets, and eventually the anti-globalization movement. You never know where things are going to go. Just throw the pebble into the pool and watch the ripples grow.

All of the great issues that the children of the ‘60s liked to think have gotten better — like gender, race, and class issues — nothing's really changed. It's just wearing a slightly different face. In that sense I could reasonably say I regard myself not as an activist, but as a revolutionary. This is an ugly, violent, system. I don't belong in that, never have. [I ask myself], How can I help people to see that, and look at better ways of managing their lives? Whether through poetry, graffiti, or music, or just talking and being, that’s my lifelong commitment. It remains utterly unchanged. Nothing's gotten any better, but then again, nothing's gotten any worse.

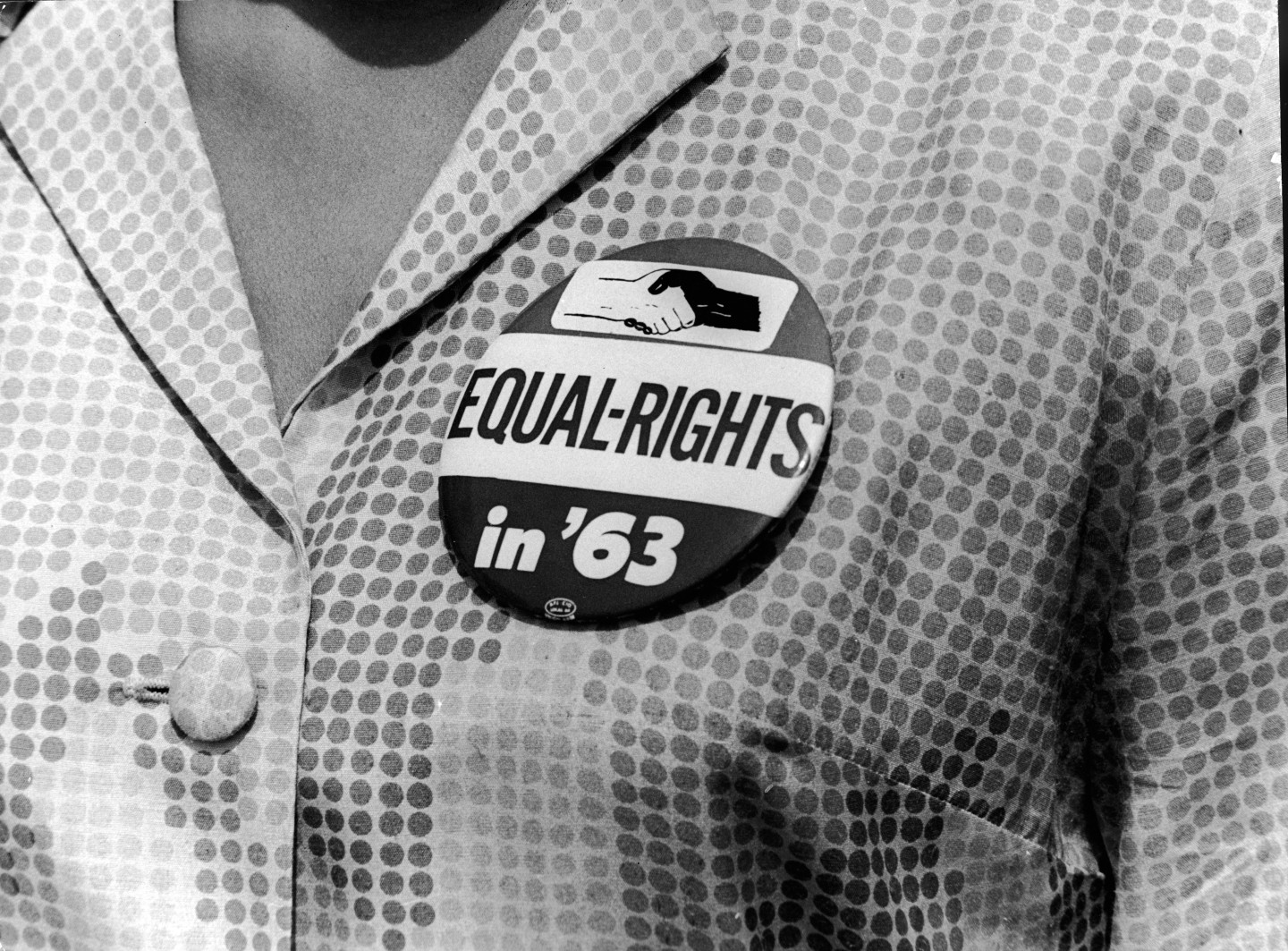

A demonstrator at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963.

Express Newspapers/Getty

A demonstrator at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963.

Express Newspapers/Getty

David Lemieux, 63

Activist, former member of the Black Panther Party (1969-1972).

I joined the Black Panther Party at a meeting in March of 1969. I was 16-years-old, the second youngest member of the Illinois chapter, and I must have been 15 for the first few weeks. I don’t like to use the cliche that I “became conscious,” but that started in seventh grade in 1966 when Stokely Carmichael was in Lowndes County, Alabama registering people to vote. That’s when I first heard the term 'Black Power.' I said, “Aw yeah, that’s what I’m talking about.”

We had an international view about how people of the world and people of color were manipulated and oppressed by outside forces. It’s the same thing we deal with today. We would not be strident and abrasive with our elders because there’s things to be learned from every generation. Wisdom is not the arrogant notion that you have so much to teach others, but the humbling realization that you have so much to learn from others. You find out what people need in communities and promote your philosophy by creating programs that draw people to it.

We need to saturate every structure in our community that has day-to-day contact with the people who are grounded in our community. It’s part of our navigating a hostile position. Some people will work loudly and some people will work quietly. The more autonomy that we have, the more ability we have to work with ourselves locally.

We were revolutionaries and, deep in our hearts, believed that the shooting time of the revolution could be at any time. I definitely didn’t think I was going to [live to be] almost 64-years-old. As you begin to use your wisdom more, you see enough have died for the people. We need to live for the people. I’m still a huge advocate of self-defense because if you’re not willing to protect yourself as an individual, how can you protect your family and your loved ones in your community?