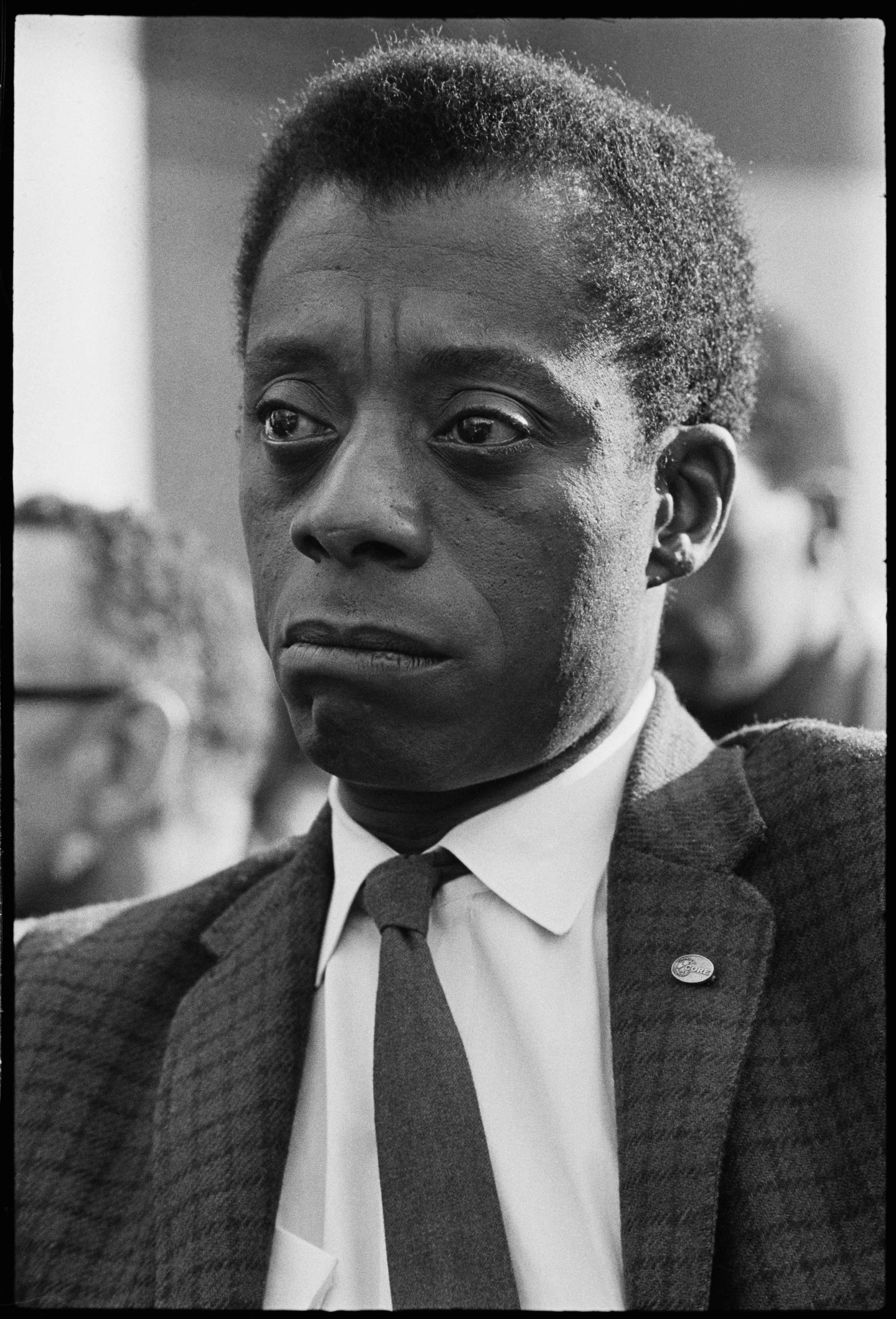

James Baldwin

Bob Adelman/Magnolia Pictures

James Baldwin

Bob Adelman/Magnolia Pictures

On June 30, 1979, acclaimed author James Baldwin, who had years before returned from Paris where he was living in protest, mailed a semi-complete book proposal to his literary agent, Jay Acton. “I’ll confess to you that I am writing this proposal in a somewhat divided state of mind,” wrote Baldwin, before submitting to tell the story of America through the lives of three civil rights figures: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. “I want these three lives to bang against and reveal each other,” Baldwin wrote of his friends, all of whom were killed before the age of 40 during the 1960s, “as in truth they did use their dreadful journey as a means of instructing the people they loved so much, who betrayed them, and for whom they gave their lives.”

Baldwin wrote 30 pages of notes of what was entitled, Remember This House, and never got around to drafting them into a book. A new, timely feature-length documentary, I Am Not Your Negro, directed by Raoul Peck, artfully imagines what Baldwin might have concluded about his country by measuring it against the lives of three of its most ardent patriots. Using Baldwin’s Remember This House notes, references from previously published books, archival appearances of the author on 1960’s talk shows, redolent stills from Old Westerns and early black cinema, and reportage from photographers like Gordon Parks, Peck constructs a vivid 92-minute narrative that places Evers, X, King, and Baldwin himself, at the axis of American history.

To describe I Am Not Your Negro as a film that indicts white American history of turning black lives into objects of violence for simply asking for equality would be accurate. It would also be true to call it a film about the ways of racism, a critique of how American history has been whitewashed. “I suspect that all of these stories are designed to reassure us that no crime was committed, we made a legend out of a massacre,” Baldwin remarks, in one searing moment, of white supremacy’s pop mythologies. And because Baldwin’s words carry the weight of history, one can suspect that he was also prophetically speaking to the adequate gains black Americans made during slavery and Jim Crow, ones that, nearly four decades later, would help usher America’s first black president in and safely out of the White House. There’s a real sense of progress in the film’s imagery if not an ominous warning in Baldwin’s weathered weariness.

Demonstrators at an anti-integration rally in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Magnolia Pictures

Demonstrators at an anti-integration rally in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Magnolia Pictures

I Am Not Your Negro renders the past as present; it is a bold chronicle that underlines just how black Americans were unfairly forced into the sticky continuum of history.

Nominated for Best Documentary Feature at this year’s Academy Awards, I Am Not Your Negro focuses on Baldwin’s enduring power, which is to say it is about the fervor of his words. Culled from vintage footage, Baldwin himself speaks through the film. At other points, actor Samuel L. Jackson narrates the author’s prose against a backdrop of contemporary images — from the concrete blocks of New York City to the fiery protests that flooded Ferguson in the wake of Michael Brown’s 2014 death. This is a film that renders the past as present; it is a bold chronicle that underlines just how black Americans were unfairly forced into the sticky continuum of history. It’s artful direction, too, that evokes the millions currently taking to the streets in the name of women’s and immigrant rights against our nation’s darker jingoistic forces.

Born in Harlem in 1924 to a poor family, Baldwin constantly clashed with his stepfather during his formative years. From early on, it was clear that he would have to find a home elsewhere: in his work and in his words. As a Harlem teenage preacher who grew into an openly gay black man — before Stonewall and marriage equality — it is as if Baldwin’s whole life, he sang “my country tis’ of thee” in a staid register. Across his many works, from the novel Giovanni’s Room to his most famous collection of essays, The Fire Next Time, there was no mistaking the song that poured from his mouth. Taking a drag of a cigarette, he would exclaim, as he does throughout the film: “I am an American!”

In scene after scene, Baldwin shows a capacity to admit that despite the racism that “corroborates their reality,” this too was his country — that “the great western house that I come from is one house and I’m one of the children of that house.” I Am Not Your Negro confirms that James Baldwin loved America in the only way he knew how: in the form of resistance and constant critique. It was a radical love, a black love.

There are moments in I Am Not Your Negro where it feels as if Baldwin is speaking directly to white America in 2017, as if he somehow knew history would continue to condemn its black citizens. “White people are astounded by Birmingham, black people aren’t. They are endlessly demanding to be reassured that Birmingham is really on Mars,” he says, referring to the city that had become a harbor of unrelenting and unimaginable white-on-black violence. In doing so, he unknowingly builds a bridge between then and now. “They don’t want to believe still, less act on the belief, that what is happening in Birmingham is happening all over the country.”

A crowd gathering at the Lincoln Memorial for the March on Washington, 1963.

Magnolia Pictures

A crowd gathering at the Lincoln Memorial for the March on Washington, 1963.

Magnolia Pictures