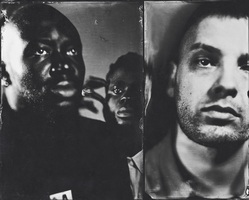

L-R: Kayus Bankole, Alloysious Massaquoi, and Graham 'G' Hastings of Young Fathers, 2011

Tim Brinkhurst

L-R: Kayus Bankole, Alloysious Massaquoi, and Graham 'G' Hastings of Young Fathers, 2011

Tim Brinkhurst

Edinburgh-based trio Young Fathers keep their circle tight and attack their music as a unit. Over a pair of mixtaopes and two studio albums, they've created a confrontational brand of hip-hop as indebted to punk ideals as it is to rap. Influences from African music also percolate through the British group’s sounds, drawing from the Liberian and Nigerian heritages of band members Alloysious Massaquoi and Kayus Bankole. After first meeting as young teenagers and forming pop group Three-Style in the early ‘00s, they soon realized that being part of the mainstream was a bad fit for three individualists with a keen DIY streak. They broke away from their management and local production company in 2011 and developed their heavy, impactful sound.

In the next twelve months they released two unrestrained and experimental mixtapes, Tape One and Tape Two, both of which are have been remastered and this week, are reissued via Big Dada. The first of these two releases taught Young Fathers who they were as a group and laid the foundations for what would come, including a 2014 Mercury Prize win, and a fearsome live reputation.

Speaking over the phone from a studio in Edinburgh in late May 2017, producer and vocalist ‘G’ Hastings spoke to The FADER about taking risks in order to rescue your career, embracing “ugliness” in their music, and finding freedom in not fitting in.

You made Tape One in Edinburgh, 2011 as the first project after your old group Three-Style. Where was your head at creatively, at that time?

I think before the tapes we were feeling a bit lost. We were dicking around as this sort of psychedelic boy band version of ourselves and had made an album that never came out. We wanted to make a mixtape of free songs to help promote the album, and Tim London, who we were working with, said we should try to make a song a day, including conceiving, writing, recording, mixing, and mastering it, all to be done by 10 p.m. each day. So we started doing that and it felt like we had fuck all to lose. We experimented, kept all of the mistakes, all of the hum and the hiss coming out of the drum machines. We would try anything; we were doing tongue twisters, puns, different subject matter and it was all manic. But it felt like something special was happening, and we had that much trust in each other as well.

We had done about eight days for Tape One and we basically ended up with a bunch of songs that sounded better than anything we had done before. We unlearned a bunch of bullshit we had picked up through the years by listening to stupid cunts with stupid ideas, these were our ideas. After the tapes, it made it hard to trust anybody, but we also created this in-house, insular thing that we were confident about. So we put Tape One out for free, sacked our management, got a lawyer who believed in us and got out of the deals we were still involved in. We basically just started again.

“Deadline” was the first song we made. It fit the tone for everything that followed it. We were all singing this melody and decided to just keep singing it over and over until it turned into a warrior chant. That changed everything for us. We realized you can do whatever you want.

At what point did you decide that doing a mixtape wasn’t an addition to what you were doing, but what you should be pursuing, full stop?

Almost instantly. We had been frustrated for years because we had two whole albums and a bunch of songs we had made since we were 14 that have never seen the light of day. The tapes taught us to just make things a bit uglier than what people are used to and see the beauty in it. When we now go into radio shows, TV shows, or even live shows, the mentality was that you get in with what you can before people question it. We just had this new belief system in ourselves, because we had dealt with so many idiots before, who knew nothing about anything, and have no taste.

The tapes also taught us how to be serious and get respect. It taught us to pick a camera, shoot our own videos, not hire people when we could just learn to do things. At the time we were just support acts for other people, and we wanted to destroy whoever the headliner and gig was. Sometimes we would try to blow the speakers so that the main act didn’t have them to play on.

L-R: Alloysious Massaquoi, Kayus Bankole, and Graham 'G' Hastings of Young Fathers, 2015.

Junn

L-R: Alloysious Massaquoi, Kayus Bankole, and Graham 'G' Hastings of Young Fathers, 2015.

Junn

“The tapes taught us to just make things a bit uglier than what people are used to and see the beauty in it.”

The first tape came out in 2011 and the second followed a year after, what was the musical landscape looking like to you at the time? Who did you see as competition?

Everybody. No one was an ally. We grew up in a very small hip-hop sphere in Scotland and, but we always felt like outsiders and found it weird how strict the attitudes and traditions of hip-hop were. Like “keep it real” or the dress code and the hypermasculinity and all that other shite that preached like a fucking doctrine.

We never really liked the hip-hop scene [in Edinburgh] and we felt outside it, so we found a way to break free from all of that stuff, rather than going one route and not being accepted and not fitting the rules, and only reaching a certain level because of that. We want our music to be us, and if we can always achieve that gut instinct, it will be us, and it will only be us. The tapes really enforce that faith.

Independence seems to increasingly be the way forward for artists at the moment. Have you noticed more of your peers catching up to your way of thinking?

Music’s got weirder since we released the tapes. Rap, especially, is really weird now. The pop industry is dying. My thought has always been that being independent is better for artists like us. Rather than standing in a long line of good looking pop stars waiting for their shot, just leave that world and make your own. I’ve seen that happen a lot more. It makes sense. Bands can make their own world up and not have to think about all that other stuff.

I was at the press conference after Young Fathers won the Mercury Prize in 2014 when you refused to speak to [right wing British newspaper] The Sun. How much do politics play into your decision making as a group?

That night wasn’t just a protest about tabloid journalism, it was right wing press in general. Anyone that has over-stepped the line with Islamophobia or bigotry and prejudice of any form, we don’t want to help them in any way. As a group we meet on the level of humanity and being decent people and not trying to enable [those] taking things backwards. We decided this before we made the tapes and it didn’t seem a bizarre thing to do. Some of the messages we got after that were hilarious. Horrible threats from readers angry that we wouldn’t speak to the fucking Sun.

Is there anything on the tapes that you think might have led to misconceptions about the group?

I can understand why people are confused by us. The tapes made us realize that we’re weird. That time was about embracing that. We cannot walk into the rap world, we can’t walk into the indie world. There was no world we could walk into and people would think, “That sounds like something I’ve heard before.” Everything that’s followed has been a continuation of what we started with these tapes. We’re just seeing how far we can push things.