Earlier this year I attended an Afghan-American conference in DC. I was in the crowded gender bias workshop, leaning against the wall behind Bilal Askaryar, the moderator of the LGBTQ workshop, when he glanced at my name tag and reached his hand gently to mine, “I think we’re related, let’s talk after.” I waited for the room to empty and we did the whole ancestry.com lite “Who are your relatives? I think my grandparents are related to your uncle” thing. I never thought I’d meet another queer muslim in my own family, and there we were, in a room full of over 50 receptive Afghans, learning about the genderbread person and how to be an ally.

This past weekend we celebrated Pride on a global scale. It was also Eid, the holy days of celebration after a month long Ramadan fast for the Muslim community. Identifying with both communities has been a long personal journey for me, and for the two holidays to fall on the exact same weekend (Ramadan following a lunar calendar), was a confluence of ideas I needed help processing.

Around midnight the first night of Eid, I texted Bilal asking if we could chat on the phone about what it means for both the Pride and Eid holiday to fall on the exact same day. How did it make him feel? I felt an energy, did he sense the same? We hopped on a call the next morning.

Hawa: So I have this group chat called “messy moozlems,” and we were all lit when we realized Pride and Eid fall on the same day, how have you processed this as a phenomenon?

Bilal: That’s amazing, I love that chat name! It’s interesting because the past couple years I thought of it as like a separate thing, there’s Ramadan and Pride, and I can’t celebrate Pride because it’s Ramadan. I have to be good. It brings up all the juxtapositions and contrasts and dichotomies within myself. What’s the definition of a good Muslim? Can you be a messy Muslim and do you still get to celebrate Eid too?

There’s an aspect of my queer identity where I want to celebrate how far we’ve come and how far we have to go. But it’s hard to march when you’re fasting and it’s going to be 92 degree sweltering humid weather. The immediate thought—which part of you do you listen to that day?

But this year it’s extra special because it coincides perfectly with Pride and Eid, especially with the context of everything that’s going on in the world. The supreme court announced they will see parts of the travel ban through. So what’s our role as queer Muslims and brown people in the US who have a voice, when our contemporaries elsewhere don’t really?

Hawa: For me, there has been so much to process in terms of not only what this means personally, but as a global citizen.

Bilal: Right, here’s a time where both aspects of our identity are more under attack than ever. Immigrant people, brown people, Muslim people, queer people, given the rise of the xenophobia in the political climate, it’s scary. The killing of Nabra Hassanen, Philando Castile. Every aspect of our identity is under attack, and yet here we are, celebrating the two most joyous days in our calendar—Eid and Pride. Pride is all about not listening to those inner demons and the rest of the world telling you you’re not good enough. And with Eid in the context of rampant Islamophobia, it’s a giant merging of resistance. You better believe we’re under attack but we’re still going to be proud of who we are.

Hawa: So you’re out to immediate family and are public with how you identify, how did they react to your celebration of Pride and Eid?

Bilal: Well my parents see pride peripherally. “There he is again in front of a rainbow flag,” and they maybe wish I wouldn’t do that. Then there’s day-to-day family like my cousins, you know how it is, we have a big family namekhuda (in the name of God). They are more than supportive, and they’ve taken it own as their own cause. My non-queer cousins are posting Pride Mubarak and happy Ramadan. They came to the pride march when I was in it even though they were fasting.

Hawa: What are assumptions or misrepresentations about being Muslim and queer?

Bilal: I was at the inauguration day protest with a sign that said “Gay, Muslim, Unafraid” sign. I heard people yell “go back to Saudi Arabia, they throw you off buildings there” and stuff like that. This tells me that, 1. People like that don’t want me to be here in the US and 2. There’s a perception that you can’t be queer and Muslim. But that’s ridiculous, here I am. You and I both can name dozens of queer Muslim friends. In some ways the misconceptions amongst the Muslim community can be more harmful to our well being. Like “oh you can be queer but you should try not to be.” We do exist, yet we feel bad about ourselves for existing because of that. If you deny us, that is denying a part of yourself, because we are part of the same family. Queer people are the vanguard of every community.

Hawa: I felt that sense of family when I was in the LGBT workshop at the Afghan American conference—like a visibility I never thought was possible within our specific community.

Bilal: I had that same moment as a moderator. I thought during the session maybe 5 or 10 people would show up, and maybe some hecklers who were just coming to see what this crazy guy is saying and report back to their families. Did I want to spend my Sunday morning talking to 50+ Afghans about being gay? Especially all the buff guys with the axe cologne...that was intimidating to me. So often because we have to be closeted, we think there are so few others but then to see you and others in one room. I never imagined 7 of us coming out in one room, that we could have that. We made that space for ourselves just by coming out and being honest with each other. This is why coming out matters and why being brave and not denying an aspect of yourself matters.

Hawa: I always struggled with denying a part of oneself for survival, or the perception of what it means to survive, versus the survival of the greater community.

Bilal: That’s what it means to have privilege. We can do this because we are relatively safe compared to other parts of the world or even the US. Growing up there’s that constant calculation of can I be honest with myself and others or will that bring irreparable harm? Can I tell this person who I am? I was afraid to open up to my parents in any way. I knew one of the biggest aspects of my identity would hurt them. I also feared for my safety, but they love me and wouldn’t do physical harm to me. When I knew I would still have a family and a safety net, I began to start telling cousins and others. We all know there are people in our communities and other communities that can’t come out. They can’t come out because it’s not safe or maybe they haven’t accepted themselves yet. That’s why we have to make sure everyone in our communities are safe and that they belong no matter what. Growing up we thought we were the only ones, that’s why we were so quiet. But now with increased visibility thanks to events like Pride and queer Muslim organizations, we can start to make stronger support networks.

Hawa: Is there a context where that privilege doesn’t exist?

Bilal: Some people are living in contexts where the idea of living authentically just isn’t an option. It’s a question of physical safety, mental health, and possible ostracization from family. I once had someone queer ask a straight family member of mine “Can you imagine living your whole life not being able to be with the person you love?” and she said “Yeah I can.” She was talking about the pressure many of us feel to marry someone to make our families happy. In some ways the challenges we face are universal, we are fighting for modern ideas like picking the person you love. But, in our cultures, we are used to sacrificing for the greater good of the family. So in one very real way that is a challenge we face that other’s don’t: explaining to well-meaning family members why we can’t sacrifice our queer identity.

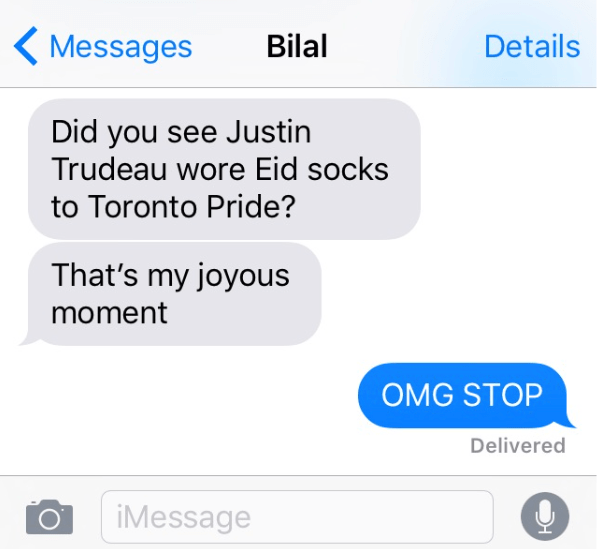

Hawa: What’s a beautiful moment you’ve had with these two intersecting celebrations?

Bilal: In DC there’s a LGBTQ Muslim group and they’re hosting an Eid brunch in a week, and I can’t wait to go. Here are all these queer Muslims celebrating Eid while every corner of the city is decorated with rainbow flags for Pride. Muslims love colorful stuff so it totally works. They won’t have mimosas but that’s ok.

Hawa: Some of us are messy Muslims.

Bilal: I really love that group, like that’s me! I’ll fast but it’s ok to be that kind of Muslim too. I remember growing up if I didn’t pray five times a day they’d tell us “Shaitan (The Devil) is gonna crawl in your mouth when you’re asleep” they were so obsessed with orthodoxy. But it’s ok, there is room for all of us to practice Islam in our own way.

Hawa: Ahhh that always was so scary! That’s what I love about my messy moozlems—we all reinforce each other’s interpretations of spirituality and religiosity.

Bilal: What about you, did you have a nice confluence moment?

Hawa: I felt like I was...internally....like blasting starlight energy through every corner of my body.

Bilal: YES, yes. I get exactly what you’re saying. And that’s enough, just to be able to have your insides shine because two of these really important parts of yourself are just about being happy and celebrating.

Hawa: Yeah. And in my reflective moment thinking of what this all means, of course I thought of you. That’s probably been one of the most important moments for me in my recent history navigating identity. That moment you reached over to me and told me we might be related hahaha. When I found out you were moderating the workshop, I realized why I was there. You helped me be brave. That whole conference actually, I felt so seen and validated. I have a new sense of pride for being Afghan because of how my peers showed up.

Bilal: Aw, I’m so happy to hear that. That’s cool, because you helped me be brave too. This is what we’re here for, to help each other.

Bilal Askaryar is a writer, international development consultant, and LGBTQ activist.

Hawa is a freelance art director, producer, sometimes stylist, and an ex-scholar. She is the co-founder of Browntourage and currently lives in NYC.