Scott Cunningham / Getty Images

Scott Cunningham / Getty Images

Last September, two weeks into the NFL season and months after Marshawn Lynch announced his retirement, the spirited running back sat down for an interview with Conan O’Brien. A few weeks earlier, Colin Kaepernick’s first acts of silent protest — taking a knee during the national anthem to call attention to call attention to systematic oppression — had already made him the season’s most compelling story. Lynch’s Conan segment was lighthearted, geared toward goofy exchanges and shareable clips. But the Kaepernick question was inevitable, and when it surfaced, it shifted the tone. “Lots of opinions out there. What are your thoughts?” offered Conan. “I really respect your opinion.”

“With what’s going on, I’d rather see him take a knee,” said Lynch matter-of-factly, pausing and gathering himself to his feet, “than stand up, put his hands up, and get murdered.” Lynch pantomimed the all-too-familiar scene by raising both hands above his head, then tucked his hands back inside the pocket of his black hoodie and sat back down. “Shit gotta start somewhere, and if that was the starting point, I just hope people open their eyes to see that it’s really a problem goin’ on.”

That it’s been less than a year since then feels impossible, but here we are. This August, Lynch — back out of retirement for his first preseason game in an Oakland jersey — nodded to Kaepernick by taking a seat for the anthem just hours after white terror struck in Charlottesville. Last Sunday, he did the same. As our Confederate apologist president dominates headlines, the sports media opinion mill is still busy churning out takes on Kaepernick, who’s waiting in limbo to sign with a team amid what feels overwhelmingly like a conspiracy to keep him out a job he deserves. A Change.org petition calling for a boycott of the NFL, citing his having been “pretty much blackballed,” is sitting on 175,000 signatures. A rally last week gathered thousands of protesters outside NFL headquarters.

Amid debates about Kaep’s free agency, other players have followed his lead. Seahawks’ star defensive lineman Michael Bennett says he won’t be standing for the anthem for the foreseeable future. Last Sunday, 12 Cleveland Browns players took a knee together to say a “prayer for peace.” Among them was Seth DeValve, the first white player to kneel in protest so far. As these acts of protest multiply, takes on their legitimacy keep piling up too. The outrage voiced by fans, pundits, and mainstream media outlets like Fox News, is widespread and extremely telling.

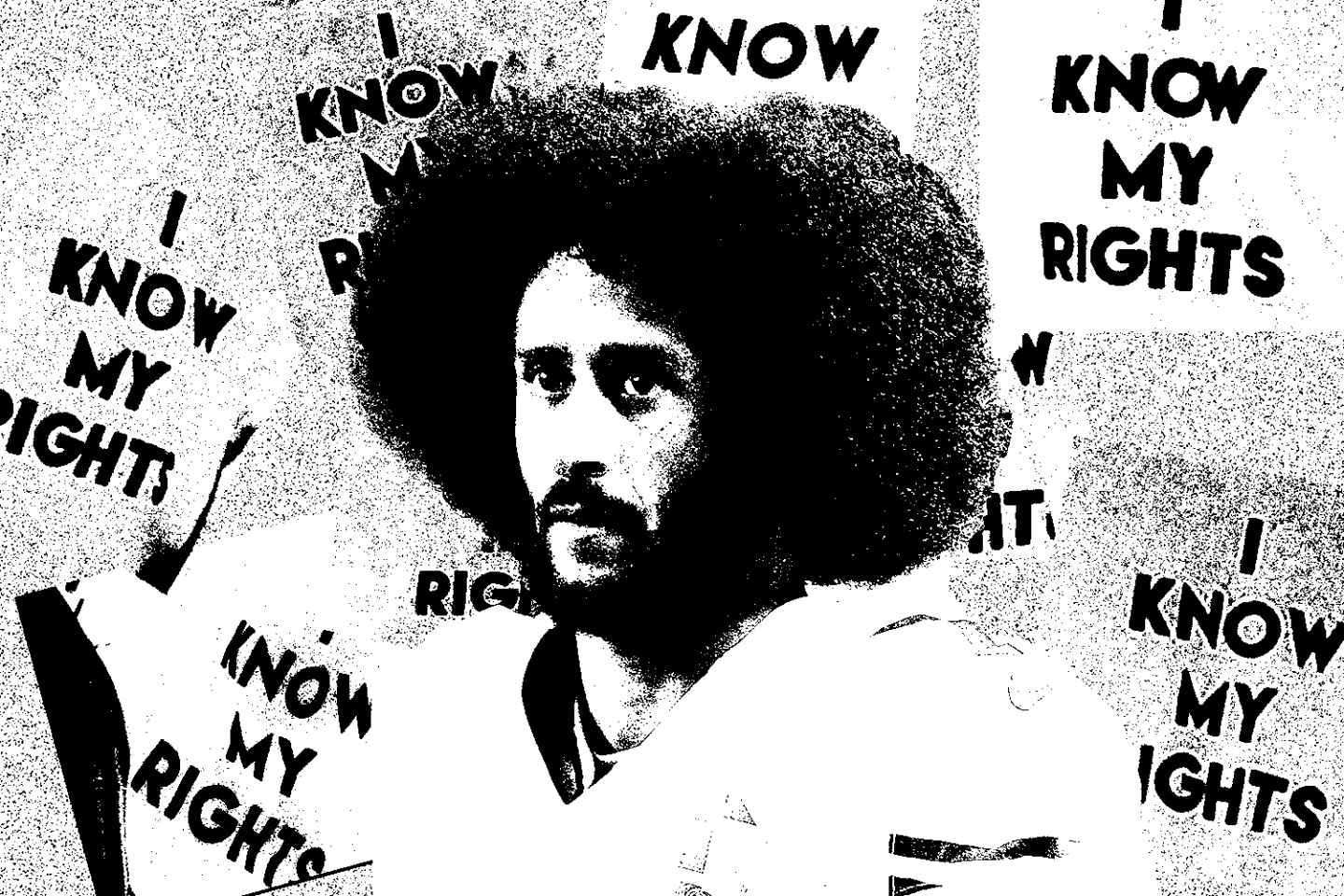

Kaepernick has had a hell of a year. After covering TIME in September, he launched his Know Your Rights Camp, a seminar series with stops in Oakland, Harlem and South Side Chicago, in which he speaks to kids of color about “higher education, self empowerment, and instruction to properly interact with law enforcement,” to ensure their safety when the inevitable happens. The campaign revolves around a 10-point set of affirmations inspired by The Black Panthers, and, as Shaun King detailed in his coverage of the program’s inaugural session in Oakland, campers are handed ancestry kits and copies of The Autobiography of Malcolm X on their way out. “Kaepernick cements his status as a cultural superhero in the black community,” read King’s Daily News headline.

He’s also halfway through donating $100,000 each to ten different organizations. On the section of his website dedicated to the pledge, a poll asks supporters to help choose between different social justice issues his next donation might go toward addressing, with options like “food justice” and “mass incarceration.” Across social media, Kaepernick presents a unified stream of content centered on black liberation and social justice. For Black History Month, he recorded a set of videos offering primers on figures ranging from Denmark Vessey to Ella Baker to Afeni Shakur. He’s posted Baldwin quotes, videos highlighting feminist icons and declarations of solidarity with Standing Rock water protectors.

Kaepernick isn’t the first athlete to use his platform in this way — the tradition of black activism in sports is long and storied, peaking during and after the Civil Rights movement with figures like Jim Brown and Bill Russell. But in terms of the stakes, the stage, and the sacrifice, a sports protest hasn’t looked like this in a very long time. In terms of its cultural politics, the NFL is uniquely repressive, a bastion of traditional masculinity and American toughness protected with a particular zeal. Kaep hit a nerve by challenging a patriotic ritual that’s part of a purposeful marketing strategy to conflate heroics on the football field with service on the battlefield.

Over in the NBA, by comparison, players operate in a star-friendly climate that’s more amenable to political discourse, even about racial justice. Lebron, Dwyane Wade, Carmelo Anthony, Russell Westbrook, and recently Kevin Durant, have all spoken up in admirable ways without facing the same level of scrutiny (and certainly without risking their livelihood). In some cases, directly indebted to Kaepernick’s. The volume of these protests, in both leagues, is indicative of a broader shift in the climate. Kaepernick has helped create a sea change in the sports universe that’s just starting to reveal its impact.

In the wake of Charlottesville, ESPN’s superstar talking head Stephen A. Smith — who dismissed Kaepernick as “a flaming hypocrite” and “absolutely irrelevant” last fall — has apparently become radicalized. “The NFL has a Kaepernick problem that’s bigger than just Kaepernick,” his latest piece declares. “Who can now doubt that the racism that Kaepernick was protesting is real — and far more dangerous and deadly and visceral than previously believed?” With the country’s racial tensions laid bare, he argues, white billionaire franchise owners are at risk of being perceived as “dismissive and detached,” or “indifferent to the plight of minorities.”

The idea that someone might need Charlottesville in order to understand arguments about racial inequity in America is maddening, as is the idea you’d need Kaep to be blackballed to figure out how fucked up the NFL is. But the fact that Smith is connecting the dots this way is telling about the cultural moment we’re in. In a climate that doesn’t leave room for moral ambiguity, everybody’s got choices to make. Football fans are going to have a tougher and tougher time pretending the sport exists in a political vacuum.

This is not, of course, a new idea. Parallels between the draft combine, or even fantasy drafts, and slave auctions surface regularly because they’re hard to ignore. The science suggests that football is giving the vast majority of players brain damage, a problem that cuts across racial boundaries, but says a lot about their employers’ attitudes toward a workforce that’s 70% black. The knock on football has always been its brutality, but the perception of the sport as unsustainable gladiatorial spectacle, as “moral abomination,” is growing fast. And the league’s popularity is already taking the hit.

Aside from those big picture issues though, the NFL is maybe most often criticized for its approach to discipline. The league is insistent on policing players’ bodies and behavior, and every year, dozens of examples are dissected for their relative fairness. Sometimes these examples are minor, checks on personal expression like fines for uniform code violations or penalties for touchdown celebrations. Others are more severe. Right now, the Cowboys’ Ezekiel Elliott faces a six-game suspension after an independent league investigation discovered evidence substantiating his ex-partner’s claims of domestic assault. Yet Josh Gordon, who once led the league in receiving, has missed two full seasons for a handful of violations of the league’s substance abuse policy. Taken collectively, these instances spell out a troubling set of priorities.

Marshawn Lynch, a highly visible superstar with a strong personality, has been policed as often as anyone during his nine NFL seasons. Most famously, he was slapped with $100,000 in fines for violating the league’s media policy by refusing to speak to reporters back in 2014. The media policy is, of course, an inane requirement, forcing players to deliver platitude-filled interviews to placate sponsors and fulfill the terms of the league’s TV deal — the most recent of which will generate teams almost $40 billion in revenue over an eight-year span. Sports media, which thrives on sound bytes, acts as a form of constant surveillance. Players, mostly young black men, are dissected and picked apart for their decisions, their “character,” their bodies and their minds.

All of which brings us back to Colin Kaepernick: in the absence of enforceable rules on which to peg him, owners have devised a creative collective punishment that sends an even stronger message. In his May piece on the subject, career NFL insider Mike Freeman spelled things out in clear terms. He had spoken to dozens of executives. “The reason Kaepernick still hasn’t been signed,” those who build NFL rosters told him, “is because of the political stance he took in not standing for the flag last season to protest racial inequality.” Arguments against his credentials can be convoluted, since Kaepernick’s star had fallen some pre-protest, following a slow decline from Super Bowl starter to backup. The consensus among serious sports thinkers though, is that our conclusion should be obvious. Guys with his track record — who win big games and front major ad campaigns — get multiple shots. The notion that he’s not good enough to help an NFL team just doesn’t hold up.

Earlier this month in an Instagram video, Ray Lewis pleaded with the quarterback, urging him to get back on the field and stop getting “caught up in some of this nonsense.” Mike Vick, a run-friendly quarterback who helped lay out the blueprint for Kaepernick’s game, and himself another player remembered as much for controversy and punishment as football, suggested he should start by cutting his afro to change “how he’s being perceived”. Kaepernick quietly clapped back the next morning with an Instagram post outlining the origin of the term “Stockholm Syndrome.” “The Stockholm Syndrome appears when an abused victim, develops a kind of respect and empathy toward their abuser,” reads the post. “This usually happens because the victim sees the smallest act of decent behavior as an extracted event which makes them see their captors as essentially good.”

Lewis and Vick's critiques are, Kaepernick suggests, symptomatic of a much broader, repressive mode of thinking. There are plenty of obvious, extreme critiques, from execs and pundits who have labeled the quarterback a "traitor" or "an embarrassment." And then there are more insidious ones. Even the critics who claim to have Kaep's best interests in mind are invested, first and foremost, in getting back to business as usual. "The football field is our sanctuary," Lewis told Kaepernick. It is a space that need not be politicized.

This is what it looks like when American escapism is punctured. The ongoing lack of acknowledgment that anything out of the ordinary is even happening, proves the point Kaep was trying to make in the first place. Starting every game with a nationalist propaganda ritual does not register to fans as being inherently political, until it’s disrupted in the name of condemning state-sponsored terror. White America has to be dragged kicking and screaming into considering things that are obvious features of others’ existence.

I wonder how much Kaepernick even wants to play, knowing the sort of scrutiny he’ll be exposed to. Obviously, he should play if he wants to. Agency is the whole point here. But does he need the league — or even the sport — as a platform for activism? His protest has never even implicated the NFL directly, but given what it’s shown us over the last year, should he play? Should we watch? Should anyone?

In his Undefeated piece last week, Stephen A. Smith advocates a shift in thinking. “The question has switched,” he writes, from “‘Who will stand up with Kaepernick to ‘Who could possibly stand against him?’” Unfortunately, the answer to that question is painfully obvious. The NFL and its staunchly patriotic fan base have exposed themselves as exactly what we knew they were all along. After all, what’s more American than perpetuating a problem and pretending it’s invisible?