Every few years, the video pops up on social media: "Dear Sister," a Saturday Night Live digital short in which Andy Samberg, Bill Hader, and Shia LeBoeuf shoot each other repeatedly with guns, set to the dulcet tones of Imogen Heap’s song “Hide & Seek.” Samberg shoots Hader, who’s writing a letter to his sister. Hader then shoots Samberg, who shoots LeBoeuf, and then all three separately, consecutively shoot Hader’s sister (played by Kristen Wiig) as she enters the room. The kicker: as the police arrive, the audience finally learns that Hader’s letter doesn't just describe what happened in exact detail but also includes a postscript in which the cops shoot each other — which, of course, triggers another undulating “Hide & Seek” cue.

The short is one of many homages to The O.C., which kicked off its four-season run fifteen years ago. This one is a reference to a now-infamous sequence in the finale of teen TV drama's second season. In the scene, one character shoots another's estranged brother. "Hide & Seek" cuts through the moment like a hot knife through butter; it’s dramatic, but also absurd in the prominence afforded to the song. The parody's endurance can be credited equally to the original scene's iconicness, and what was perhaps the show's most influential characteristic: its game-changing use of pop music.

Granted, The O.C. was hardly the first teen show to fluently use pop songs of the day; the original iteration of Beverly Hills, 90210 regularly featured musical guests like the Flaming Lips, Christina Aguilera, and Maroon 5. But in the years since The O.C.'s reign, the role of the music supervisor has morphed into a tastemaker position. Music supervisors have wielded their expertise with great success on major shows like Grey’s Anatomy and Friday Night Lights. More recently, the effective practice has extended to present-day teen-oriented shows like Riverdale, 13 Reasons Why, and On My Block.

“Promise Not To Fall,” by the Portland producer Human Touch, hadn’t yet been released when it was used on 13 Reasons Why. And Brooklyn artist Tattoo Money’s song “Levels” was so beloved by On My Block’s music supervisors that he’s now working with them directly to supply new songs that will appear on the show’s forthcoming second season. Sometimes, it seems like the shortcut to finding out about the latest up-and-comers is to check out what’s soundtracking teen shows.

For example, curious listeners can subscribe to unofficial show playlists on streaming services and instantly share their newly-found faves on social media. But music supervisors themselves — including Alexandra Patsavas, whose work on Gossip Girl, the Twilight film series, Grey’s Anatomy, and The O.C. has left an indelible impact on pop culture at large — see the function of their role quite differently. “The scripts have been written. The story is unfolding from the writers," she says. "I'm part of that creative team — working to carry out the hopes of the producer, looking at the footage, and trying to pitch the right song."

She's currently working on Hulu's Runaways, which reunites her with O.C. producers Josh Schwartz and Stephanie Savage; her workflow — discussing song options with the producers, clearing samples and licensing songs, watching rough cuts of episodes, and working with post-production teams on syncing picture to sound — hasn't changed over the years, even as the technology behind creating episodic song lists has. “When I started [doing] comps [in 2000], those were made by hand," she explains. "I'd sit with a CD and a recorder, and they were all done in real time.”

Being able to finding bands on Myspace in the mid-2000s helped ease the labor behind the process, as did the changing norms that meant you could successfully request more instrumentals from artists in addition to original cuts: “I remember getting calls from marketing departments, and I was shocked. Record company marketing departments were like, 'This is an opportunity.' I struggled a bit in my earlier days to convince bands that a placement on a TV show wasn't going to whittle away at their indie cred, that we were going to use [their] music respectfully. It was a way to connect to fans.”

“I struggled a bit in my earlier days to convince bands that a placement on a TV show wasn’t going to whittle away at their indie cred, that we were going to use [their] music respectfully.” —Alexandra Patsavas

Ben Hochstein and Jamie Dooner, who worked on MTV’s Awkward and helped build word-of-mouth for Netflix’s On My Block through the bright soundscapes they curated, point out that the rise of streaming — as well as the binge model of TV season releases — represent more big changes to how they approach their work. “In the network space, you're thinking of things that will air within two or three weeks, and you can kind of chase trends in a closer way," Dooner says, "but we finished [work on On My Block's first season] in December [2017] and it didn't air until the end of March."

Hochstein adds that the most obvious drawback of curating a contemporary sound months ahead of a release: “[Your work] comes out about nine months to a year later, and by then all those cool songs you got are in Target commercials or other shows. Everyone's sort of picking from the same pool of what's cool and what's current, so it definitely kind of hurts your heart a little bit. We found the newest and coolest thing, and we don't wanna get scooped.”

And that musical cherry-picking is the goal of music supervision: of wanting the exact song for the exact narrative moment. Season Kent, whose most recent credits include Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why, Love, Simon, and the upcoming film adaptation of the Y.A. hit The Hate U Give, says that digital music discovery has significantly opened up the variety and specificity of songs she can potentially discover: “I'll go down a rabbit hole, which'll help me find something I'm actually looking for — an artist I've never heard of, or a sub-of-a-sub-of-a-sub-genre.” They're regularly pitched music for specific projects from labels and bands, but she and Hochstein both namecheck Spotify’s playlists as useful discovery tools, especially the ever-popular Discover Weekly playlist.

It's telling that the music supervisors I spoke to stressed that their work supplements the overall narrative project — that it’s never just about the music. Well-placed musical cues not only influence how you feel about a particular character or storyline, but about yourself, especially during your formative teen years. “I'm still nostalgic about movies I watched in high school," Kent says. "When it's done right, these stories are taking into consideration who these teens really are — that's the difference with the Y.A. stuff now, versus what it was before, so it's even more so for kids to relate to it in that sense.”

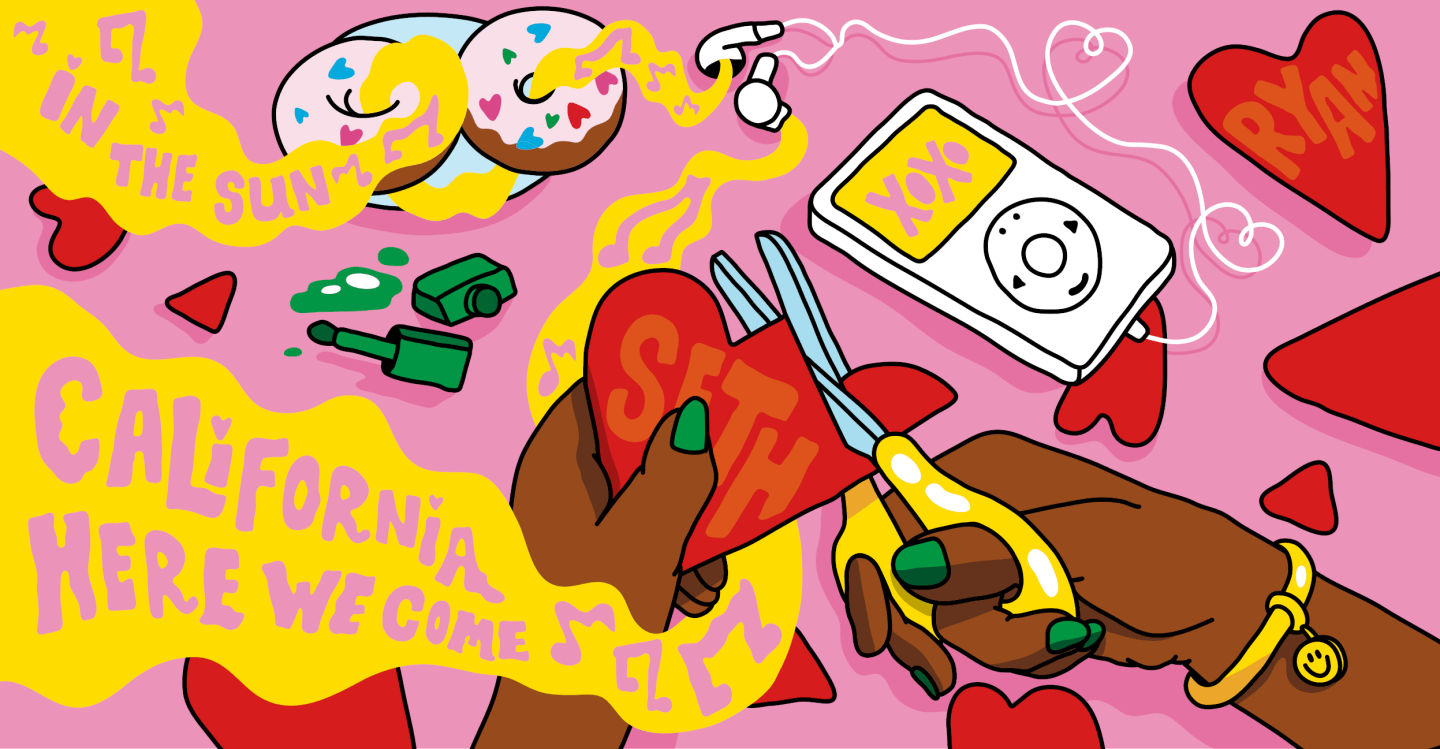

For Maris Kreizman, writer of the blog-turned-book Slaughterhouse 90210, her first experience with must-listen TV was on the original Beverly Hills 90210, later finding her pop culture doppelgänger in The O.C.’s Seth Cohen. “He and I were obsessed with the same music, and I didn't need ‘his’ suggestions because I was finding this stuff on my own," she says. "All of these bands I thought I invented were Seth Cohen's favorites; that was very painful for me then.”

Eventually, her ire turned into self-identification, and well-placed song selection even changed her mind about shows like the CW’s One Tree Hill: “I hate-watched it a little bit, but there's this really ridiculous episode where Peyton is kidnapped or locked in her basement with a psycho, and the Veils start playing. That was a band that I was really into and took seriously, so just having that juxtaposition there made me feel like, 'Maybe I should be paying more attention to the show.'”

Whereas Kreizman trawled early MP3 blogs like Aquarium Drunkard, writer and cultural critic Ira Madison III experienced a different side of mid-2000s music discovery through TV syncs: “You had to download it illegally — or hopefully [the show] would tell you the song at the end of the episode. I'd always be Googling lyrics.” While he credits The O.C. as kickstarting his interest in the interaction between music and TV, he cites Glee as an example of one of the first shows to explicitly connect the experience of hearing a song on a show to the act of immediately buying the music — which has now morphed into immediately streaming said song and, as the industry hopes, a deeper dive into artist catalogues and affiliated playlists: “Even long after [watching those shows], it was still fun to listen to those songs and go back and listen to them.”

“We’re at an age now where [if a song airs on a show], you’re gonna be able to find it somewhere else.” —Ira Madison III

Times have definitely changed, and even as Kreizman and Madison III fondly recall the past, the former laments, “I feel like I'm supposed to consume and consume and consume, and then there's no savoring. There's no investigating and going back and thinking back to how this one song made you feel. I also find it interesting that I haven't watched a TV show in a long time that had a 'Music by,' or 'Featuring' [in the credits].”

Madison III also explains how social media has changed the way music discovery unfolds: “We're at an age now where [if a song airs on a show], you're gonna be able to find it somewhere else. Or it'll be discovered there and people will be talking about it on social media. Insecure, a show I love, uses a lot of really good new music — but people will immediately be tweeting about the new song, or you can look through the Spotify playlist if you didn't watch the show.”

Suffice to say, these feedback loops have evolved since The O.C.’s debut. Patsavas recalls, “iTunes was new [then], and I remember working with Warner Bros. Records — who put out the soundtrack — and Warner Bros. Television — who produced the show — providing lists of what we were gonna air that night. It was fascinating to be able to participate in the audience's response, which I hadn't been able to do before.”

Kent’s recent work on 13 Reasons Why was a hit on the music discovery site Tunefind, so much so that she kept in contact with site founder Amanda Byers: “She said, 'When you do season two, it'd be really great to have all the music from you beforehand, So when the show goes live, I have all the accurate songs for every episode,'" Kent says. She did so for season two, and is taking notes on these search counts and how they might change “six months from now, or right before season three airs.”

Despite insisting that they hew to scripts or the producers' vision, music supervisors aren’t immune to the influence they wield, which manifests itself not only in the potential payoff of the sync itself but in the long-game continuum of meaningful storytelling — crafting a memorable moment amidst the increasingly saturated pop-cultural glut. This means that quantification metrics like search counts only barely touch the actual impact of their work, and when it comes to the human-machine algorithms that drive streaming platforms, music supervisors are careful to delineate the difference between targeting a general audience and using music as a vehicle for storytelling.

Dooner cautions that, though he and Hochstein do place an emphasis on artist discovery in their work, “The songs are the tools that we're using to tell the story. If the songs all work, they make a good playlist, but that's not what we set out to do.” Kent explains further, “I don't think some computer algorithm could help me pick a song based on punching in [words]. What's special about what we do is, [the sounds of] 'sad,' 'scary,' 'regretful,' or 'harmful' mean different things to different people.”

When sound and picture come together in symphony to craft the heady musical memories that bloom during your teenage years, the results are iconic in a way that lingers. Madison III can certainly attest to that: “For shows that really want to connect with teenagers, if you use music to accentuate certain scenes, it not only makes the scene better, but you'll remember that scene every time you listen to the music. It's why everyone remembers ['Hide and Seek'] — it takes you back to that moment.”

And that's also the goal for Patsavas, whose work is perhaps the locus of modern music supervision’s spotlight. Thirteen years since The O.C.’s second-season finale, she finds the “Hide & Seek” SNL parody and its continued resurgence as “unbelievably flattering.” Her work — and, by extension, the heart of her profession — still aims to create a sonic bubble that, once pricked, unleashes a torrent of feeling and memory around the story at its center: “I'm still a big stickler for sequencing. You have to be taken away to that world. When you're listening to that collection, to that companion, you should be thinking about Gossip Girl, or thinking about The O.C. It always has to tie back in. It's always an O.C. song.”