“I live a nervous life. I gotta look around and watch my back from police...people want to kill me. I can’t be driving around in $100,000 cars on the run, listening to soft-ass shit.” –—Drakeo the Ruler

Drakeo calls his work “nervous music,” and it sounds like it was forged out of mud and dread. He grew up deep in the Hundreds and used to rob houses. His videos are full of guns and nobody looks comfortable. A lot of rappers will tell you they rap to launder but Drakeo can convince you of it; he’s also as stylistically daring and atmospherically gripping as nearly anyone in his generation. I’m plagiarizing myself here, but it’s a shame that “mumble rap” was coined as a pejorative for a different style of hip-hop, since Drakeo’s raps are built largely from the kinds of phrases you would mutter under your breath, and they’re delivered that way, too.

There are three earlier tapes that are essential and dozens of scattered loosies and scathing features, but everything crystallized on Cold Devil, which came out at the tail end of 2017 and hasn’t been surpassed by any rap record since. It’s coiled around drug runs at discount gyms and home invasions in Koreatown, caked in police chalk and littered with Neiman Marcus receipts. He says things like “Princess cuts on my wrist like an emo bitch” as if his throat is disintegrating.

What makes Drakeo’s network of friends and relatives, the Stinc Team, a compelling rap collective is that unlike similar cliques in L.A. and other cities, the rappers are not all deploying variations on the alpha dog’s style. Ketchy the Great, who put out a very good tape called Free Sauce this January, often raps in something close to a bark. He’s serrated. Sayso the Mac is not exaggerated like Ketchy but is closer to a full, outside voice than Drakeo ever gets; Ralfy the Plug is Drakeo’s blood brother, and understandably the closest comparison, but even he raps with a little more exuberance. And then there’s Bambino, who sounds as if he ingested everything that’s been happening, vocally speaking, in Atlanta this decade and croaked it back out, distorted and strange.

“Let’s Go” pairs Bambino with Drakeo; Bambino’s hook glides in low in the mix –– this might be unfinished –– and at the end, when he raps about his jewelry making people cry, he sounds like he’s about to crack himself. (The song’s also co-produced by Fizzle, one of the key architects of the sound in the city at the moment.) The Ruler’s verse darts from Teflon-piercing bullets to Picassos (and to his manager, Picaso), disco-ball strobe lights to ruined Margielas. Drakeo says this might have been the last song he made on the outside, but he can’t remember for sure.

But the song is a showcase for 03 Greedo. A cursory Google will tell you about the words LIVING LEGEND tattooed across his face, about bouncing around basements and dilapidated houses in the South and Midwest before landing in the Jordan Downs projects in Watts. Critics (including me) have talked about his ability as a synthesist, and it’s true: Greedo’s been able to break Baton Rouge and Young Thug and decades of California eccentrics into component parts and arrange them into new, vital, lonely masterworks. That collage work is not the point of Greedo’s music –– rather, those are the tools he uses to rappel deep into his own brain. His best songs are pained and paranoid.

The subtext (and often the text) in much of Greedo’s work, both before and after it became clear the 2016 charges were going to end with a long sentence, is the toll coming in and out of jail has taken on his brain, his family, his friendships. He does this with a voice that can warble or punch you in the gut, be drowned in post-production effects or rendered nearly naked. His extended verse on “Let’s Go” –– they let him run for 20 bars –– is colored by exactly that. He raps about jetting around the country to find weather cold enough that it would justify wearing expensive sweatwear; he raps about riding around unnamed locales listening to Cold Devil. He says he bought a condo simply because he walked inside and had deja vu.

It’s hard to overstate what it meant for the city’s scene when Drakeo and Greedo finally joined forces: the “Out the Slums” video is a good place to start, Drakeo praying –– Lord, keep me away from these bums –– and Greedo’s chains rattling together to sound like a Neptunes beat. They also linked for the brutally frank “Ion Rap Beef” (“And you ain’t do it right if not detectives come”), where they taunt the LAPD and explain the process of choosing a good posthumous picture for local news broadcasts. Magnetic rappers are popping out of every crevice in L.A. right now, and it seemed for all the world that Greedo and Drakeo (and the Stincs) were going to be the pillars of the movement for years to come.

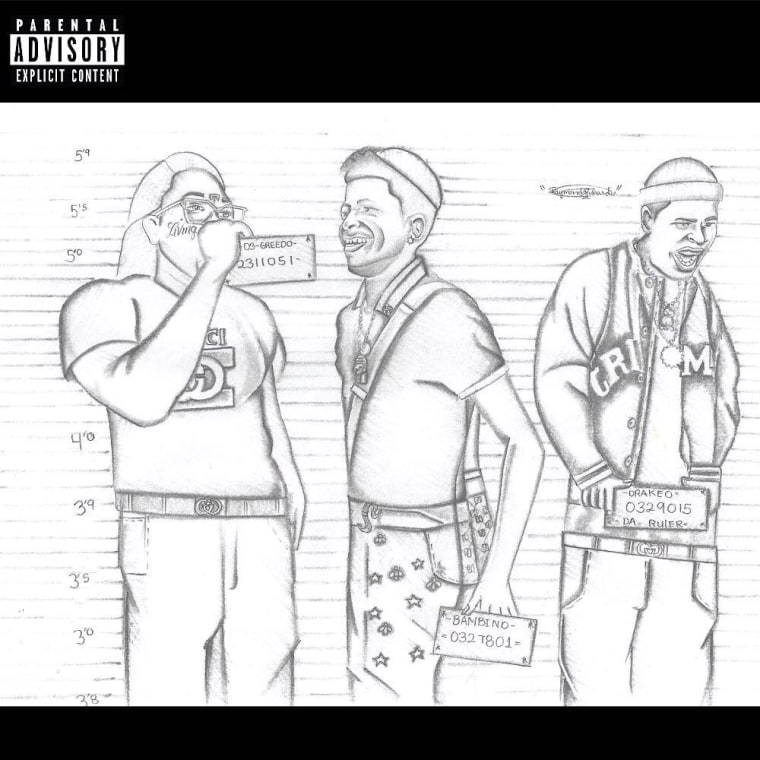

But none of these three men are free to promote this song or talk about it with critics or play it on stage. Last summer, Greedo flew to Texas to begin serving a 20-year sentence that stems from gun and drug charges he caught in the summer of 2016 in that state, enhanced by old L.A. County felonies. A few months before Greedo turned himself in, Drakeo was arrested while running errands by police who showed him his own music videos and rapped his lyrics at him. He’s currently inmate #5198096 at Men’s Central Jail in downtown L.A., awaiting trial on charges of first-degree murder and attempted murder, as well as multiple counts of conspiracy to commit murder. The prosecution’s case rests largely on a jailhouse confession of disputed veracity, and so Drakeo’s music –– and that of the rest of the Stinc Team, almost all of whom were arrested, jailed, and charged in the weeks following Drakeo’s booking –– has been crucial fodder for the city as it attempts to paint Drakeo into a legal corner, as prosecutors have done to rappers for decades.