Corey Taylor doesn’t believe in guilty pleasures. He’s amused that Rihanna is a fan of Slipknot, the masked metal band he fronts, but not surprised. “Your heart knows better than your head does half the time,” he tells me in an unaffected yet sage-like growl. We’re speaking backstage before Slipknot’s Toronto show from an air-conditioned green room overlooking Lake Ontario; on the table in front of us is a red cake shaped like the number 1, to celebrate the chart-topping debut of Slipknot’s new album We Are Not Your Kind. “There's still a lot of fire in this band,” the 45-year-old Taylor says. “That’s where we’re lucky.”

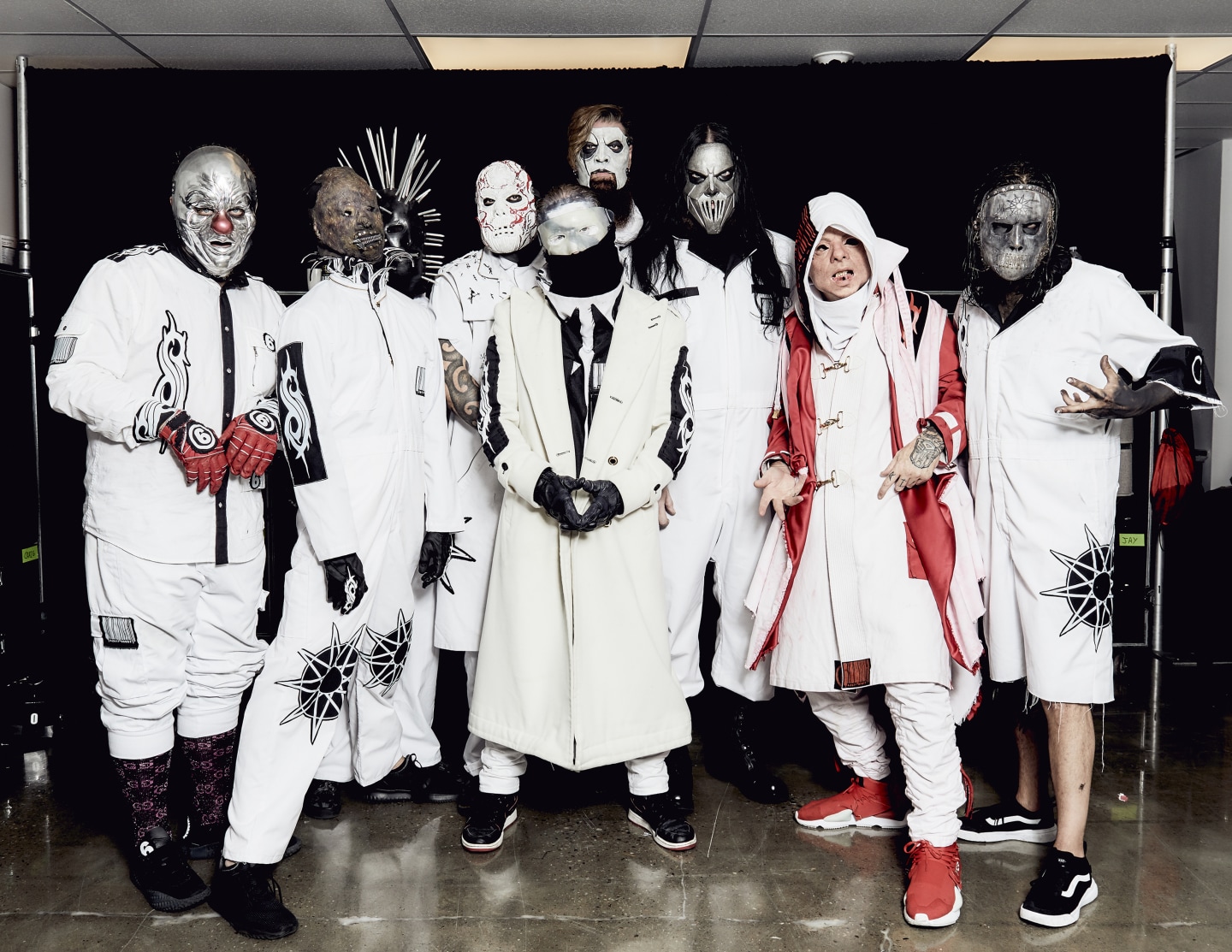

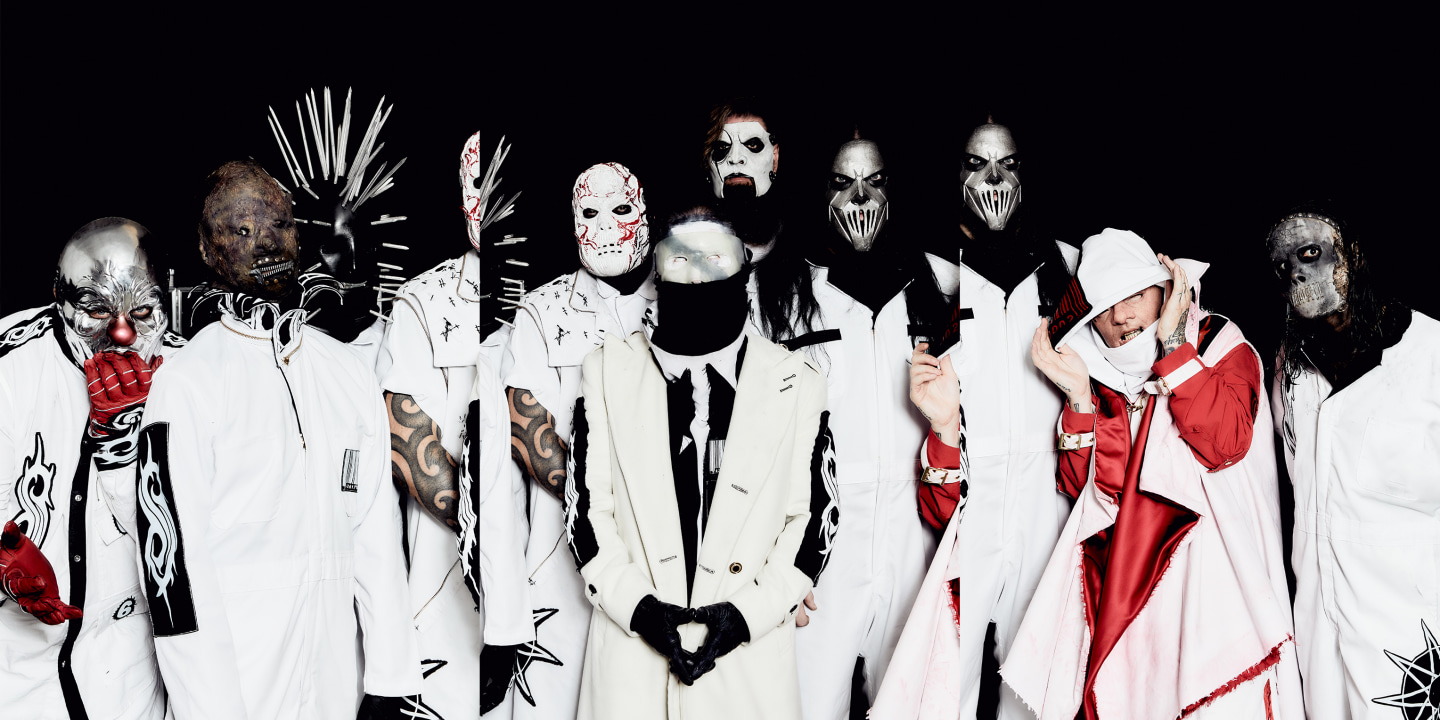

You could always tell Slipknot were relentless just by looking at them. The band emerged out of Iowa in 1999 with nine members in red jumpsuits and individual masks; the pageantry covered every possible nightmare. Their self-titled debut merged rap, hardcore, and thrash, leading to the band’s swift designation as “nu-metal” by critics, an imperfect branding that would soon become a stench. 2001’s Iowa, the band’s tempestuous second album, is best summarized by one lyric from “Disasterpiece”: “People make noises when they’re sick.” Slipknot found an equilibrium on Vol. 3 in 2004, but were derailed by the intraband turmoil that marked 2008’s grim All Hope Is Gone, and the death of founding bassist Paul Gray, whose memory is enshrined on .5: The Gray Chapter, released in 2014. But even without the tragedy, addictions, and betrayals, something about Slipknot seemed unstoppable.

We Are Not Your Kind is Slipknot’s best album since Vol. 3. Taking its title from Slipknot’s empowering loose single “All Out Life,” WANYK is filled with similar moments of uncompromising selfhood and harsh reckoning. Taylor constructed his lyrics after the collapse of what he describes as a “toxic relationship,” and structured his pain around demos fashioned by guitarist Jim Root and Shawn “Clown” Crahan, Slipknot’s guiding creative voice. Songs like “Unsainted” and “Orphan” are Slipknot at their anthemic best, while “Birth of the Cruel,” “Red Flag,” and “Solway Firth” feature heady headbanging experiments with industrial textures. At the height of their powers, Slipknot achieve a violent synchronicity of its elements, like wolves on a hunt — in that respect, WANYK is the sound of a wooly mammoth being torn apart.

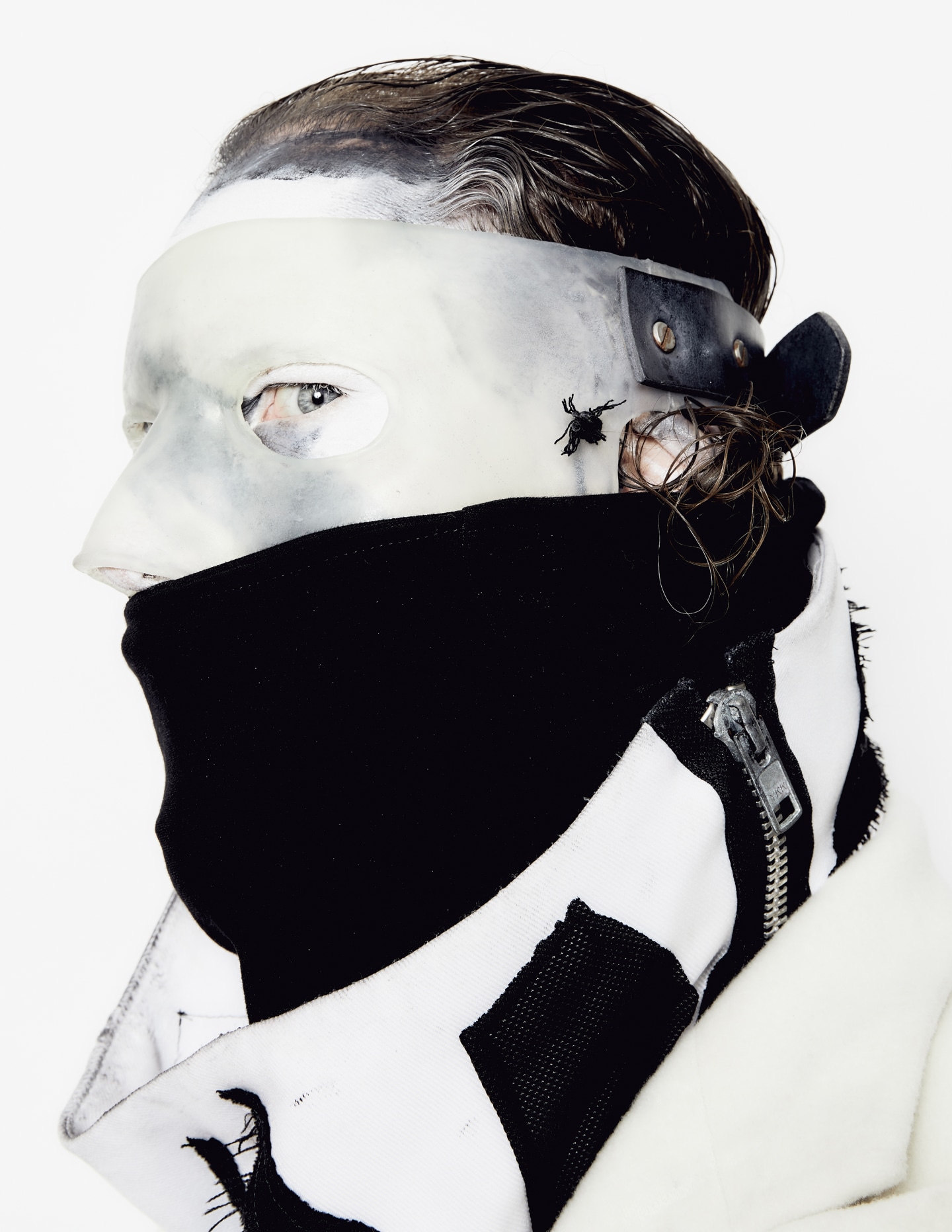

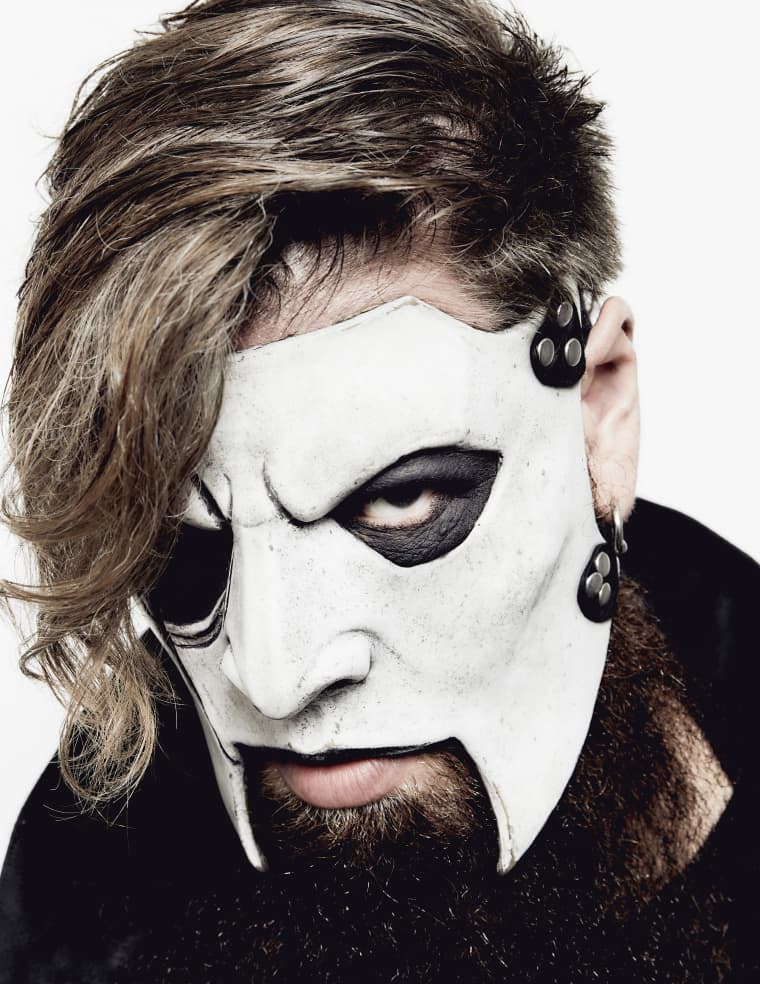

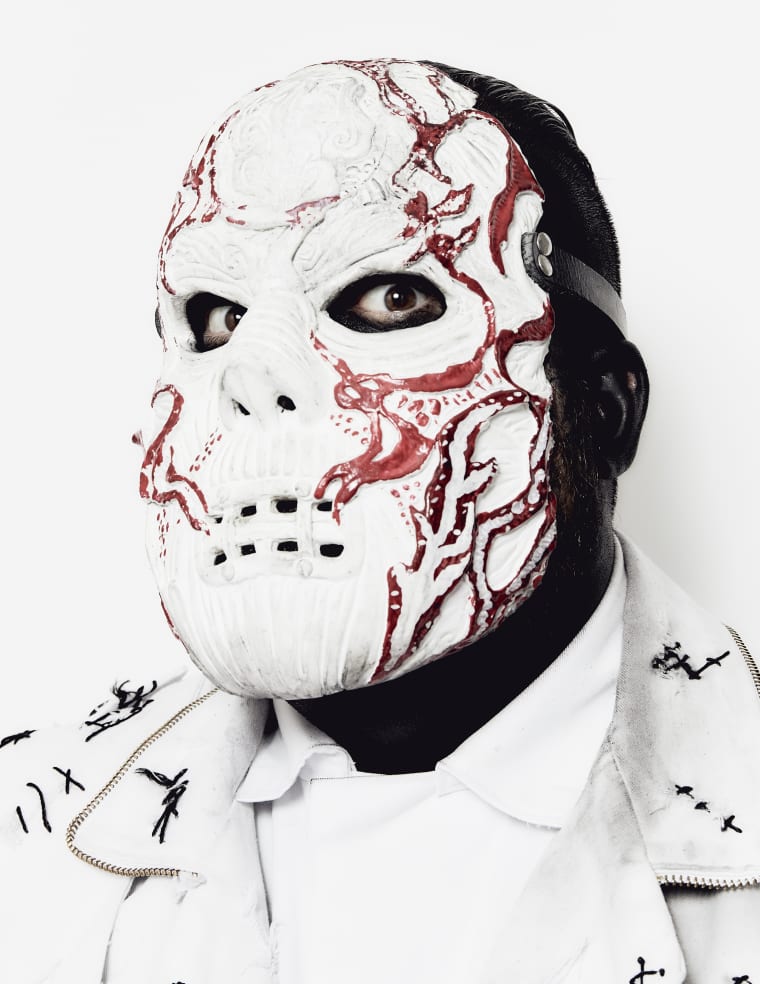

After the interview, I head to the packed,16,000-capacity amphitheater to watch Slipknot perform. Taylor has changed from the black fedora and shirt he wore during our conversation into his uniform: a psychedelic black-and-white checkered trenchcoat and pants, with a mask designed by horror legend Tom Savini. It is a combination of Japanese Noh, a translucent Bobby Hill Halloween mask, and Heath Ledger’s Joker. In person, it is deeply unsettling. With each member of the band performing like they are the only one on stage — scratching and clawing at their masks or stroking them like beards — the line between persona and performer disappears. Slipknot’s appearance may prevent cynics from taking them seriously, but it’s more clear than ever the group has nothing to hide. Even after two decades at the mast of one of the biggest cult bands in music, Taylor still has a few more surprises to share.

I’m going to start this off with a confession. So, it's 2001, I’m a lapsed Christian kid living with a religious family, and Iowa has come out. I buy the CD, listen to it one time front to back, and I immediately have a six-month resurgence in my Christianity.

Wow, really? [laughs]

You scared Jesus back into me.

You’re welcome. That's a first. I've never heard anybody finding religion after listening to us. Usually they were repulsed by us to begin with.

This question would be obvious if you were a horror author or filmmaker, but do you take any pride in the fact that both your music and your image has the capacity to scare the shit out of people?

Yeah, like a sick kind of schadenfreude. But this was always more art than gimmick for us. My whole goal was to make people, at least at first, uncomfortable. Not scare them so much, but to just put them at that sense of unease so they could really feel the level of art that was going on.

If you can put someone off of their norm and get them out of their comfort zone, then they really experience art, to me. But it never got by us that people were really, really scared. I mean, if you've got a clown on the band, it's obvious.

Speaking of comfort zones, the recording process for this project, did it ever get as hectic as it did in the Iowa days?

The Iowa days were hectic because of the drugs and the alcohol. That made everything horrible. Fast forward 20 years, now it's just about staying healthy. The greatest thing that I did was discover the fact that I wanted to do this. That came with really trying to take care of myself again.

I walked every day to the studio to make sure that I was at least breaking a sweat [and] getting back in the headspace of putting action into the music. A lot of people [in the studio] go from sitting, to singing, and back to sitting. I'm like, "Fuck that, man.” You gotta put the action in. If you can't put the action in it nothing's gonna move you.

What was so wonderful about making this album [was that] it had the same kind of darkness and the same sharing that I'd felt when I was doing the first two albums, but it was so much more focused [with] a maturity there that wasn't there before.

I think that We Are Not Your Kind is your most efficient album since Vol. 3. On Iowa, All Hope Is Gone, and The Gray Chapter, to different extents, Slipknot sound like they’re lost in the wilderness. Now, it sounds like you have some kind of structure.

You're absolutely right. [With] Iowa, we wanted to make the heaviest album ever made, and the songs were kind of thrown together on the go. We wrote half of that on the road. Vol. 3 was when we first really tried to have a vision for something. It started with Clown going, "Let's really try to push the boundaries of this and see where we can go.” And it was because of the turmoil on All Hope Is Gone, and the solemnity of .5 that you could feel that that same kind of mindset wasn't there.

With this album we came into it like, "Let's build something.” This isn't just a collection of songs. This is a story. This is a completion. This is exactly what we've been trying to get back to for a long time.

“I’m still trying to find the best way to say something, the best way to sing something, the best song to write.” —Corey Taylor

Slipknot’s music and style is simultaneously inspiring progressive metal bands like Code Orange and Vein, and a new generation of rappers like XXXTentacion. How does it feel to have this wide-reaching influence?

It’s something that we've never really thought about until it started happening, because we've always kind of been an island unto ourselves. All these artists who we've inspired, it was almost accidental because we were just trying to do our own thing.

We're still almost regarded with disdain by the metal pantheon, which is fine. I don't give a fuck. I'm here for them [points to the stadium]. So, at one point it's gratifying that people are quoting us as inspiration, but at the same time it hasn't changed anything ‘cause people still hate us.

People have always tried to push us into the nu-metal thing. They've also tried to include us in with the American wave of heavy metal because of how aggressive we were. I mean, we've had some blatant hip-hop, not even the fucking nu-metal side, but blatant hip-hop.

You sound like you’re rapping on “Spit It Out.”

Oh yeah, absolutely. But people don't realize is that's a hardcore song. That's me channeling H.R. [of Bad Brains] and everything that I grew up listening to, and just spitting as hard as I could.

I know a few years ago that you got into some trouble after saying Kanye West wasn’t a rock star.

Oh, yeah.

But I think Slipknot and Kanye West have something in common. You’re both commercial powerhouses, but for very different reasons, you’re both still underdogs. Each time you drop something there’s a lingering sense of, “can they do it?”

You're not wrong there. Plus we've never been satisfied whether it's creatively [or] commercially. You can tell the bands that have, because their quality drops off quite a bit, and it's that sense of dissatisfaction that has always powered true creativity. For me, I'm still looking, I'm still searching, I'm still trying to find the best way to say something, the best way to sing something, the best song to write.

You said recently that you've just learned to like yourself in the last few years. Have you ever had trouble reconciling these deep feelings of depression with the need to create, or does making stuff just come naturally?

It's just natural, to be honest. I've had clinical depression my whole life. A lot of it comes down to growing up the way I did. A lot of it comes down to the abuse I went through. A lot of it comes down to the places that I found myself when I was on drugs or alcohol. If you look at any true artist, they're going to tell you that there's some self-worth issues.

There's a lot of self-loathing that goes into the creative process. And I will tell you this: liking myself hasn't dampened that, which is weird. You'd think it would. [On We Are Not Your Kind] I’m speaking about a very specific time in my life, the remnants of a toxic relationship. I had to get out of [it] or I was going to die, and I don't mean just from a physical death, but a complete erasure.

The best thing I did was to get out of that relationship. But I knew that that was going to be the one thing that was going to have to talk about if I was going to be able to work my way through it.

On We Are Not Your Kind, the first lyrics we hear from you are “I’m counting all the killers” on “Insert Coin,” and they’re repeated on the closing track. Does that phrase have a special significance, or is it just there because it sounds cool?

You'd have to ask Clown. A lot of the intros and a lot of these songs come from his mind. It's also what gives every album its color. This album, man, is a stark gunmetal. Whereas Iowa is the deepest black you could ever even think of. The first album is red, obviously. But then you have Volume Three, which is like a blue. All Hope Is Gone is like a dirty green. And then .5 is more of a subdued gray.

The “killers” line is about standing on the precipice of change in your life. Realizing that when you're all by yourself and that you're in a horrible fucking place in your life, you can count all the things that are holding you down. Not even anchors, but just fucking bullets coming at you. And you can either charge through it and try to get to safety or you can just let them fucking kill you. Which one feels more righteous?

You've written a book about your own supernatural experiences. Right now we’ve got UFO footage on the cover of The New York Times. Do you feel like we're living in a turning point in history?

You could ask me that without the fucking UFOs and I'd say yes. We're on the precipice of an upheaval that we haven't seen since fucking '68. It's fucking scary. I'd never thought about being in a time when it was this bad, until I woke up and realized that my President was retweeting fucking white supremacists.

Judging by your Twitter presence alone, you’ve shifted a bit from your 2017 interview with Larry King, when you said, "I want to give him a chance, but he keeps shooting himself in the foot.”

I had to start my book [America 51] over twice because of what happened. I could not believe that people would vote for a fucking moron like him. That's what insults me the most. You can paint him as racist, or egotistical, or a tyrant, or all of this shit: He's a moron, and the people who fucking voted for him? Fucking morons too. It doesn't matter why they voted for him, whether they are racist, or they want money. They've done more to set us back even further globally than anything I've ever seen in my fucking lifetime. And that's coming from somebody who wrote a whole fucking song about George W. Bush. This guy, it's going to take us 20 years to fucking undo half the shit that he's done.

Honestly, I come at it from a fan standpoint. Most of our fans are of color, are from different countries, speak different fucking languages, love different people. I don't want my fucking fans getting killed. I don't want my kids getting killed.

And the worst thing is that it has emboldened fucking racism. And people can fucking talk that and fight me on that all they want. I called it in my book. I'm seeing it now. Why do you think that in “All Out Life” I said, "I'm tired of being right about everything that I've said"? It’s because I am. It sucks.