As Honey Harper, William Fussell translates country music through avant-pop and his own Southern childhood — so it's no surprise that he gravitates toward the idea of late singer-songwriter Gram Parsons' "cosmic country” style outlined in Michael Grimshaw's Redneck Religion and Shitkickin’ Saviours? Gram Parsons, Theology and Country Music: "...The creation of a new way forward, a way to musically heal the separation and increasing divisiveness of late modern life.”

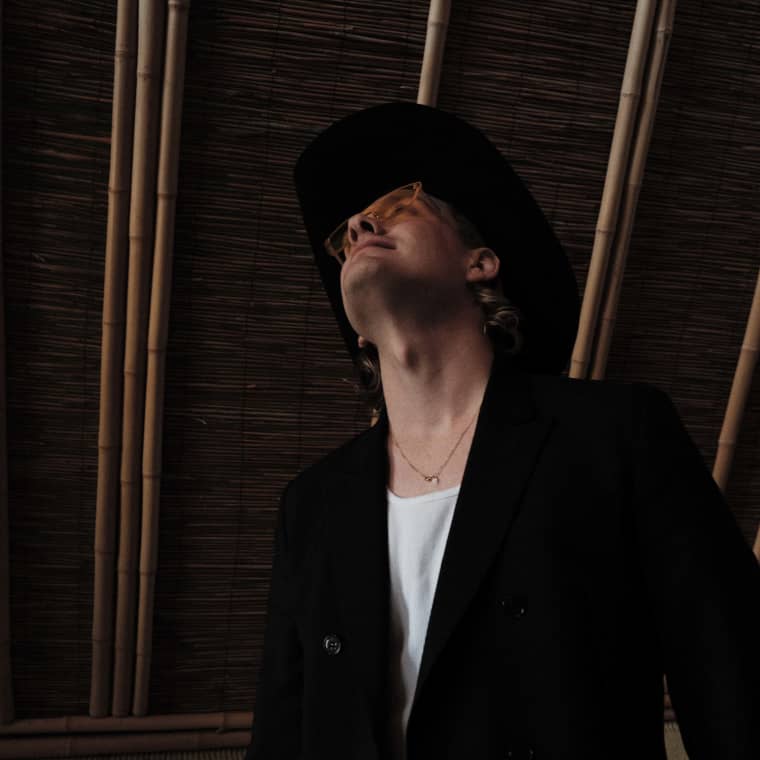

This point of view led Parsons to take country — a genre made of global influences and mixed with class experience — toward a broader understanding in and of the world itself. With his mop of platinum blond hair, rhinestone decorated eyes, and soft-knit tops paired with a cowboy hat, Fussell’s approach similarly includes a softened aesthetic of masculinity, one that complements the work of queer country artists like Paisley Fields, Lavender Country, and Orville Peck. Following his debut EP Universal Country from 2017, his debut LP Starmaker helps create a new way forward for people desperately looking for that place.

What makes Starmaker different than Universal Country?

They come from a similar place in the sense that it's country music for people who don't like country music — or also, in a sense, trying to help people recognize the beauty in something that may traditionally come from a geographical stigma. Starmaker is a bit more personal, whereas the EP was trying to reach out a bit more. In general, Honey Harper has been coming from this standpoint where everything was based on this ideology of that — trying to create an aesthetic around it, as well in Gram Parsons' idea of what it is and how it comes across. Trying to actually create those sounds is something that is still coming out, and I was hoping to combine and connect the dots a bit in a really simple explanation of that.

What's the appeal of cosmic country's sound and aesthetic, as opposed to more “traditional” country music?

In the original idea of where cosmic country came from, it still was traditional in the sense of the instrumentation it used. Originally, it was an alternative to how that music could be approached and consumed. In order to do it more so, you just keep on pushing that barrier about how it can be listened to, and I think now is a great time. It's been having a moment. Now is a great time for it to just keep on going. The more technology we have, the better. The synthesizers you can use to create a more cosmic sound are pretty cool. Also, you listen to it online —it doesn't matter if it's analog anymore.

You've worked within avant-pop in the past, but you grew up listening to country music with your parents.

I was born in South Georgia, and I lived in South Florida for a bit before I moved to Atlanta. My dad was an Elvis impersonator. I went to a Southern Baptist Church many times a week with my parents and was a part of that whole thing for a very long time, and then I tried to find my own way. My mom and dad showed me a lot of different music growing up. I grew up watching Grease with my mom all the time — I was very into that, and disco. My first CD ever was disco. If you'd told me when I was growing up that I'd start making country music, I'd be pretty shocked.

Do you feel like you're gravitating away from indie and pop sounds you've previously explored and more into country-adjacent music?

There's so much beauty in the sounds of what country can get across. Growing up, it was very hard to separate who listened to that music. All of the people making that music are artists, creators. Whether or not they believe what they're singing, they come from a place closer to it than a lot of other people, or you or I. We probably relate to them more than we think. They think "I'm living in this idea" for so long that they have the opportunity to escape that thought process. I feel like I have free rein in whatever I want to do with it. It's really helpful in trying to create a different sound.