Gretchen Felker-Martin’s Manhunt is more human than its critics

The author of the riveting new book discusses maximalism, safety, and Starship Troopers.

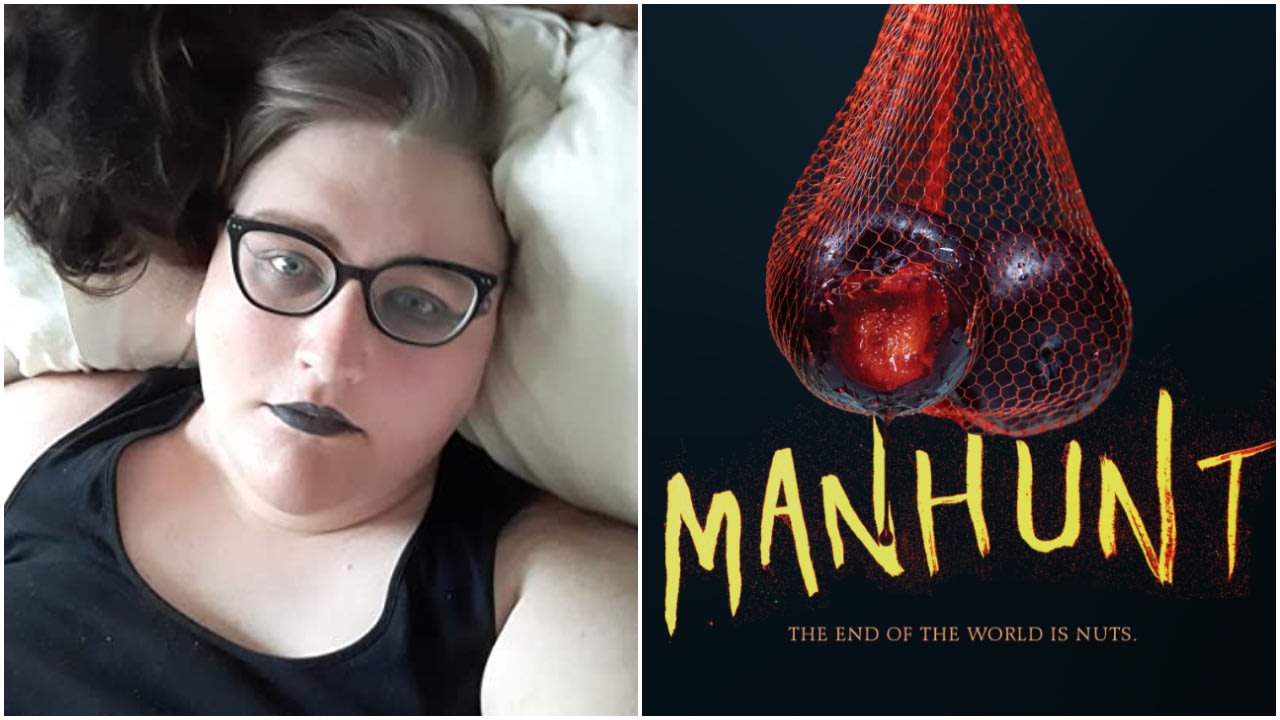

Gretchen Felker-Martin. Photo via author.

Gretchen Felker-Martin. Photo via author.

Gretchen Felker-Martin writes horror fiction that sticks with the reader like a plague boil sent by the divine. Her new book Manhunt is stomach-churningly violent, but as with all great horror works, it delivers revelation after revelation of our own nature. “You have to press [the reader’s] face to the fire,” Felker-Martin says over the phone from Massachusetts, “and show them the value in holding it there. Because the things that make us uncomfortable are not necessarily morally meaningful.” From her beginnings as a self-published trans female author and horror film critic to the present day, Felker-Martin has brought a keen understanding of both the genre and the human viciousness that inspires it.

In both quality and content, Manhunt offers remarkable, terrifying, and deeply human new visions. Set in the near future, where a plague has turned all biological males into bloodthirsty monsters, Manhunt follows two trans women, Beth and Fran, who scavenge through the dregs of society. Their task: harvest organs from the roving packs of zombie-men to manufacture the hormones they and the surviving women need. Their biggest threats are not the feral creatures, but other women: gangs of militant TERFs (Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists) that have seized cities and send death squads to execute trans people in the streets.

The vividness of Manhunt is encapsulated in its sex scenes. A stark contrast to popular modern fiction’s anodyne approach, Manhunt’s fornication is as charged, filthy, complicated, and as multitudinous as the real thing. Trans, fat, and disabled bodies convene together in a celebration of the lesser-seen flesh’s pleasures, depictions that Felker-Martin is aware will chafe even if it isn’t her primary intention. “Me expressing through erotica my feelings about those bodies is inherently political [because] there's so little fat and trans and disabled sex in any medium,” she says. “People are very afraid of sex in modern art. So I think just by including it at all, I'm de facto pushing back against that, even though that's not my primary goal. I'm not trying to fight a culture war. I just think that sex is really important.”

Still, the culture war has arrived at Felker-Martin’s door. For years she’s been the subject of vicious attacks from real-life TERFs — mostly online, she tells me, though she has experienced violence in person. It escalated last week when numerous right-wing media outlets discovered Manhunt and its mention of J.K. Rowling. The Harry Potter author became a godhead in TERF circles after writing that pro-trans movements “[seek] to erode ‘woman’ as a political and biological class and offering cover to predators like few before it.” Rowling’s death in Manhunt – killed by an accidental fire at her mansion in Scotland – was either incorrectly reported or wildly decontextualized to paint Felker-Martin as bloodthirsty or bitter in service of a growing anti-trans agenda gripping the United States and beyond.

In reality, Felker-Martin's book is a glorious slurry of human carnage and richly-earned hope as nuanced as the current moment demands. Earlier this week I got to speak with Felker-Martin about writing Manhunt, the public’s reaction, and creating deeper meaning through maximalism.

The FADER: How have you felt about Manhunt’s reception since its release in February?

Gretchen Felker-Martin: I could not be happier. Honestly. It seems divisive, and I think anything worth reading should be. People are very excited and very repulsed. I mean, the number of other trans women who I've heard from talking about how the book puts things on the page that they had never felt comfortable saying out loud, that's really… All I want is to reach out to people who don't get to see their own weird little internal flables and complexes in genre and give them a reminder that they're not alone with those feelings.

How do you see the book fitting into the literary subgenre of gendercide?

I don't think that it could really exist without the context of The Screwfly Solution and Y: The Last Man, and the gynocratic utopian novels from the second wave of feminism, none of which are particularly good. This genre has been having a moment off and on for 50 years. I do like a lot of these stories [and] I find a lot of value in them as pulp and as thought exercises and all the wonderful things that science fiction and horror can be, but Manhunt is very much firing back at them and saying, “you have a very simplistic view of the world. You don't really understand the bodies and the gender roles that are the center of your story.”

Can you expand on that?

I think that almost every gendercide story breaks down along chromosomal or hormonal, or sort of nebulous gender lines in a way that reality doesn't. What's a man? How do you define a man by behavior or biology? And you're always going to hit a stumbling block when you try to include everyone who you would think of as a man if you saw them and exclude others [whom] you wouldn't.

Manhunt tries to get granular about this. And you can't account for everything as a single author, but I've done a lot of reading. And I gave that my best shot. It's very strange to me that a genre that is all about examining what a gender role is and how gender roles might behave in different sorts of vacuums or absence, doesn't have a very firm grip on things like what's a woman, what's a man. And I think it's because they don't have any interest in the internal sense of those things.

I think that when you take a setting like Manhunt in this grizzly, post-apocalyptic world where survival is day-to-day, you have a chance to literalize the anxieties that drive daily trans life.

I wonder if perhaps there was a fear on the author's part of approaching these concepts and not being able to do it in a way that wasn't too academic or heady. And I think one of Manhunt’s great accomplishments is that you ask all of these questions in a pulp setting.

It's like Chesterton said, "literature is a luxury, fiction is a necessity." I think that pulp gives us how to think about ourselves because it's so sensual. It's so rooted in the world. And I mean, I'm a nobody dirt bag from a town of 600 people in New Hampshire. My frame of reference in the world begins in the metaphorical gutter, if not the literal one. And that's where I try to speak from and to. I don't know that I could really do a good job doing anything else. I guess my real thought is if you're afraid of being able to communicate these ideas, why are you writing this book?

When you set out to do anything that by its nature is going to have to include sort of sweeping implicit and explicit statements about the world, you just have to start from the position that you might fuck up really bad, and everyone will get mad at you. That's fine. It doesn't really bother me. People have been mad at me as long as I've been conscious.

I believe that the best horror has characters that are experiencing magnified and remolded versions of real terrors that people actually face, and Manhunt embodies this. Was the book’s post-apocalyptic setting helpful in exploring the different ways that contemporary trans people feel unsafe?

I think that literalizing the violence that we live with in a way where the experiences of the trans people who are the most vulnerable to transphobic and homophobic violence, that experience becomes the new baseline. Because of course, there are many historical moments in which trans people were exterminated en masse, and then of course you have day-to-day violence, lethal and domestic.

To bring feelings and this awareness of what it's like to live in a hunted state to an audience, you have to exaggerate. I'm a big fan of maximalism and the art of melodrama, because I think that sometimes when you show something bigger than reality, it's only then that you're able to communicate that feeling to another person. Our emotions are much larger than the world around us acknowledges, because of course we don't live in a cartoon; the world doesn't reflect our state.

I think that when you take a setting like Manhunt in this grizzly, post-apocalyptic world where survival is day-to-day, you have a chance to literalize the anxieties that drive daily trans life. And that's a really powerful tool for communication. It's also, I think, a tool for developing solidarity because it can tell different kinds of trans people, “hey, we're all sort of laboring under this cloud of ambient misery.”

Politics is who you love and who you're willing to kill. That’s really it.

That maximalism also applies to how you wrote TERFs in the book. The way that you depicted them, it reminded me of this moment in Starship Troopers: after the human soldiers’ raid on the bug home planet goes awry, the lead general gets fired on TV and is replaced with a Black woman. It captures how institutions can use identity as a mask to conceal the evils they perpetrate.

Absolutely. I was just actually re-watching that movie and showing it to my sibling, and we had a conversation about that exact moment. That is what people mean when they say “optics-only politics.” I remember this God-awful press release from a couple of years ago about how the first woman had just risen to the rank of some type of general in the Marines. And it was just so repulsive to me on so many levels. And I remember seeing all of these women from the armed forces saying, "rah,” and “you go girl," and it's like, “oh my God, you're all fucking insane. You have no conception of feminism as anything other than you want your turn to have your finger on the button that blows up at everyone brown in the entire world."

That sort of utopian feminism and political lesbianism and other aspects of the second wave of feminism, which would sort of morph and mutate into a modern landscape of TERFdom — which of course now is sort of a blanket term for everything from rabid, vaccine-denying, bizarro parents with trans children that they hate and are afraid of, to actual radical feminists who are whipping up violence against trans people, and use this as a wedge issue — that's the world that they want. They want to replace men. And if you do that without examining anything underneath it, if you do that without taking white supremacy above the roots, then you get more white supremacy.

There's a guy who runs an account called Dick Nixon on Twitter, which is this extremely lengthy historical cosplay as President Nixon [that] tries to replicate Nixon's thought process. And he has this wonderful quote about stupidity and the different types of stupidity that I think about all the time. And one of the types that he lists is the stupidity of the insect or the inbred dog, something that is constricted by its nature to just sort of savage anything you put in front of it, that really doesn't have any thought process. And it is just this mindless, implacable, stupid eating machine. And that's TERFs. You talk to them and it's like banging your head against a brick wall that hates you. There's nothing going on behind their eyes. They will contradict themselves in the span of a sentence and march on happily.

When I had finished reading Manhunt, I was left feeling just as hopeful by its message as I was repulsed by its violence.

I believe really firmly that trans people and queer people can build the world that they want together. And that even though it's miserable and it's endless work and it's really shoveling shit against the tide in so many different situations, it can be done. And the work is worth doing on its own merits, because what is the point of eking out an existence if nobody loves you? If you aren't connecting with the people around you? [With] the people who need you and taking care of your community?

I have fuck-all time for a consensus. It's a trivial issue for people to whom politics is a game of checkers, something to pass the time for people who aren't smart enough for chess. Politics is who you love and who you're willing to kill. That's really it. And I think that if you don't come to politics willing to fight for what you believe, willing to throw away the idea that consensus and assimilation are necessary end goals, what are you doing?