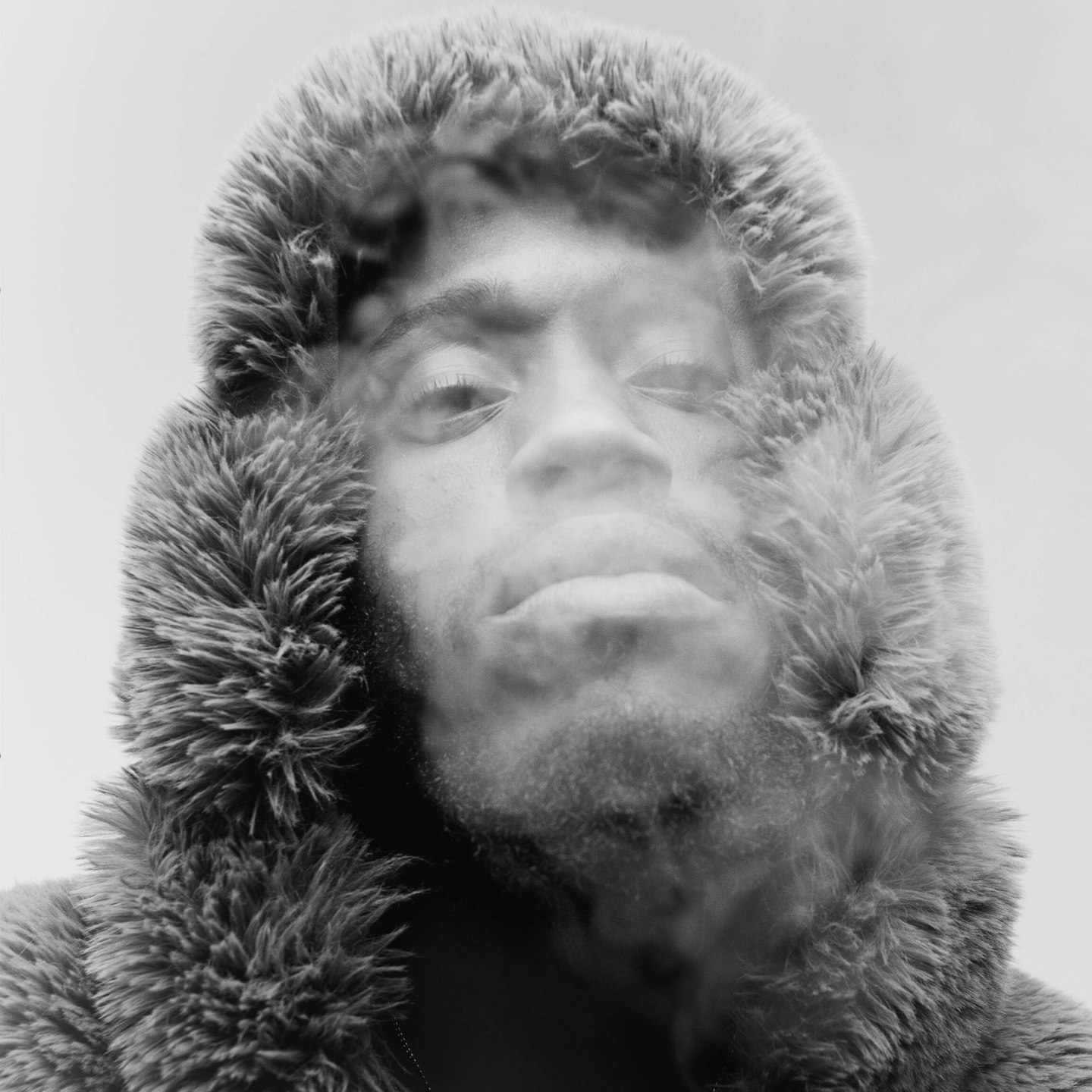

It’d be hard to describe the Airbnb Maxo’s holed up in as anything other than a man cave. Squished into the walk-up’s living room is a bed, a massive TV, a lonely dog bed, a smoke detector that won’t stop beeping, a few bar stools, and a set of leather chairs that look like they were lifted from an AMC Dine-In. Nearly every piece of furniture has red highlights. And then there’s Maxo — tall, lanky, and hunched over in a chair in the corner, still recovering from a late-night, cross-country flight. His inconspicuous aura brings a strange tranquility to the otherwise cluttered room.

It’s slightly warmer than it should be on a December afternoon in Brooklyn, but still chilly enough for him to throw on a few layers before stepping out to get smoothies. “I’m good,” he says, laughing off the cold. “That’s why I’m jacketed up. I got a thermal, a sweater…”

Maxo is in New York for Pigeons & Planes’ rising talent showcase, No Ceilings, where he’ll perform a medley of unreleased songs from his forthcoming album, Even God Has a Sense of Humor, out February 22. Next to the other acts on the bill — Atlanta’s Kenny Mason (the headliner), Ben Reilly, and Al-Doms — the Southern California-raised rapper is a little out of place. His patient flows and meditative, often self-reflective raps don’t have a chance of caving in Market Hotel’s floor like the moshpit-ready anthems the others have in their catalogs. But when the show’s mentioned in passing, he doesn’t seem nervous about it. I’m not even sure he’s thought about the clashing energies.

“A lot of the time, the music is there for conversations I can’t even have with the person in real life [because] I haven’t built up the courage. So I talk to a mirror.”

There isn’t an exact moment when our conversation shifts from small talk to interview, but when traveling comes up, his words grow taut. I gesture to my recorder, and he gives a knowing nod, taking a moment to gather his thoughts. “It’s something about the West Coast that has us stuck in that place,” the 27-year-old, who split his formative years between Ladera Heights and the Inland Empire, says. “I remember the first time I decided to get up and go somewhere. I just quit my job and I was like, ‘I’m finna go to New York and sleep on these niggas’ floor.’ I was feeling that shit in my stomach.”

Maxo doesn’t like to feel “stuck.” If he starts to feel physically bound to a location, he isn’t afraid to get up and book a ticket elsewhere. He took a “life-changing” trip to Senegal with his mother in 2017, where they journeyed around the country for three weeks with a guide who — when his mom complained about the heat — plainly answered, “I’m not God.” Years later, there’s still a sense of awe in his voice as he speaks of a spiritual experience his mother had while overseas. The trip’s enduring scene comes from the airport, where a gate separating arriving passengers and aggressive taxi drivers, seemingly on the verge of collapse from the number of humans pushing against the wiry structure, transformed from mayhem to mundane after three weeks.

His approach to moving on from something emotionally can take a bit more time. “A lot of the time, the music is there for conversations I can’t even have with the person in real life [because] I haven’t built up the courage,” he admits. “So I talk to a mirror.” His music is enamored with the past and future, earnestly pondering countless “what ifs?” with sobering optimism. Following Maxo’s discography, you’ll hear him capture his in-the-moment thoughts and attempt to figure out where his heart’s leading him in the moment. It’s a coming-of-age story without an ending; Maxo comes back to revise the manuscript whenever it’s no longer recognizable to him.

The very first project that Max Allen put out, 2015’s After Hours, was a 7-track tape recorded alongside VIK, a beat-making friend he met while attending Chaffey College (“Straight to cassette; sock on the mic, like it was the ’90s”). Released on the Alaska-based cassette label Burnt Tapes, it’s the grainy, hungry-for-the-world project that every teenager who’s spent hours listening to way too many L.A. beat scene mixtapes to count dreams of making. After Hours would be the start of Maxo seriously considering rapping — viewing music as a way to process the turmoil of his personal life, the stresses of growing up Black in America, and seeing his older brother grapple with mental health issues.

A collection of singles and an EP, gold in the mud, would pad out the space between After Hours and Maxo’s next milestone: 2017’s Smile, made with Inland Empire producer LastNameDavid and with Maxo’s older brother — and main inspiration — Sharp rapping his first verse in years on “AppleTree” as the tape’s sole feature. At times, Maxo sounds like an even scrappier Below the Heavens-era Blu, lashing out at the world and retreating into himself in the same breath: “Now I don’t think y’all heard me, man, I need every dime / Cover up my scars with a check, I do this every time,” he rasps on “Same Hoodie Since ’05.” His voice is noticeably haggard on a few tracks, but LastNameDavid’s submerged and jazzy production softens his blows, infusing the project with downplayed tenderness.

“Maybe my approach with things in real life was a little more abrasive,” he says. “Right now, I’m way calmer than I was then. I’m not letting shit get to me like that. But at the time, I was too sensitive and I didn’t even see the cycles of that to know how to deal with it.”

“I done experienced the most — every feeling — to just get to this point and be present for it… Honestly, I don’t regret nothing because it really is life aside from new music. I’m a different person right now than I was when I started this.”

On his 2019 Def Jam debut, Lil Big Man, the gaze of his writing turned inward and his delivery mellowed out as he meditated on his early 20s. His plainspoken reflections garnered buzz from publications. But even after that release, and joining the label he once rapped about hoping to sign with, it felt like he was still working in his own quiet corner of the world, occasionally popping up on a song with one of his peers. There’s a version of this profile that starts with the proverbial Bat Signal of “Where’s Maxo?” and details the four years between albums, wondering — as many have online — if Def Jam fumbled his career. For Maxo, the reality isn’t quite black and white.

“I just use [the label] so I could make the music I imagined making, so I could almost connect history a little bit,” he explains, “and connect pieces that wouldn’t have connected if I wouldn’t have made a move to connect that shit. When I was doing shows for nine people, 10 people… going to San Diego with [Pink] Siifu and lojii, and we was just mobbing together and it wasn’t nobody there, I was like, ‘We hard, though. What is something we could do to bring another light to what we doing?’ You can’t just live off potential.”

Even God Has a Sense of Humor is a realization of that dream, combining his most focused rapping to date with an even more ambitious scale of production than on Lil Big Man. Scattered across the album are contributions from long-time collaborators like LastNameDavid and Siifu, as well as tender performances from keiyaA, Liv.e, and Melanie Charles that are like celestial gut checks. Maxo began piecing the album together about a year ago with help from Mount Kimbie’s Dom Maker. (They connected after meeting at a studio session where Maxo mistook someone who sent him music for someone Maker had collaborated with.) Maker assisted with arranging the pile of tracks Maxo had accumulated over the last few years into a collection of 14 songs that explore anxiety, faith, and family. The result, Maxo says, is a collection of “feelings that I need to leave behind.”

“I done experienced the most — every feeling,” he says with an exhausted laugh, "to just get to this point and be present for it… Honestly, I don’t regret nothing because it really is life aside from new music. I’m a different person right now than I was when I started this.”

Listening to the record, you can detect Maxo’s desire for control of his fate surging through each song. It’s the most direct he’s ever been with himself on an album, no longer satisfied with letting life wash over him. The blend of jazz, buttery sample-based production, and sandy atmospheric pieces underscoring the project give it a defiant glow, like a bronze statue still standing after an intense tornado. Maxo’s favorite song is “Nuri” — a winding, three-minute odyssey that takes him from Senegal to toasting Clicquot to fumbling opportunities he dreamed of. It’s the closest thing to a thesis statement on the album, condensing years of fuck-ups into a single sheet of ink-smudged loose-leaf.

“48,” last year’s Pink Siifu-featuring single, captures the album’s immediacy and sense of purpose. The video’s first half reveals a gauzy, LastNameDavid-produced track from the album where Maxo’s eerie singing voice sounds like radio transmissions from the astral plane. In the video’s second half, a blossoming Syreeta flip from Madlib — who is, expectedly, the only producer on the album he wasn’t able to work with in person — caresses their verses. “Shootin’ for the moon, landin’ on a star / Knowin’ if it’s true, then it’s gon’ lead to what I need’,” Maxo raps.

Growing up, Maxo would spend a lot of his free time at the park playing basketball. Between games, he found himself watching everything that went on from the benches: fights, almost fights, broken arms, and “niggas in the parking lot bullshitting.” It’s a fitting origin story for his observant and pragmatic writing style. On Maxo’s past albums, the conversations he has with family members and stories of his friends behind bars are filtered through his strained conscience, presented without commentary as if he were handing advice off to anyone listening. The worldly anxieties he expressed back then aren’t exactly gone on Even God Has a Sense of Humor, but it’s clear that he’s ready to move into something different, embracing uncertainty in the hope of getting unstuck once again. He’ll deal with whatever comes next as it happens.

The FADER: What was it like when you came back from Senegal?

Maxo: I was trying to share this experience that changed my life. I was so eager to share, and I noticed for some people it made them uncomfortable, ’cause they never experienced it. And I wasn’t coming at it like that. I was just coming at it like, “Bro, we have to go, we have to figure out how to go together.” But it’s like some people are so simple minded in how they thinking that the first thing they gonna react to that is, “Don’t nobody want to hear about that.” Then I realized how simple-minded we was out here. That shit really fucked me up, bro.

You think it’s a fear?

I don’t know. I don’t know what that is, man. A fear, maybe. Insecurity, maybe. But it’s like, “Why can’t we just think of that? Let’s all go. We need to experience [this] together. That’s always how I’m approaching shit: “Yo, let’s do it.” [You] can’t control how people react to things. That’s one thing I had to learn the hard way, by just being me and not even doing nothing to nobody, fucking up because I’m learning, adapting as I learn, growing as I go. Niggas don’t even give you the chance to experience life and learn and live and grow anymore. You gotta be perfect when you born. That ain’t how it is. If you ain’t fucked up a few times by the time you 30, you doing something wrong.

It feels like existing in the public eye can get to be too much.

You feel me? I do appreciate the times when there was not as many vessels to know publicly and [ways] to perceive a motherfucker. Like, just eat what that nigga put on the table. Everything’s so invasive, bro. But with music, what I’ve noticed is that [it’s] something I could really only be transparent with in a certain way. That’s also the root of this shit, to why it saved a nigga life. I’m excited to drop this shit, man.

“Both Handed” has a back-and-forth to it, a feeling of uncertainty where you’re being called to act but you don’t know if you should.

The indecisiveness of the decision — of being certain on what could happen or making that leap and not knowing, and the fact that you’ll never know, and that making you feel nervous and scared. People don’t acknowledge fear, especially men. I don’t give a fuck, bro; I be scared sometimes. I don’t give a fuck what anybody gotta say, and that’s okay. Sometimes, as a man, I don’t know what to do. That song is like real life, like in the decision of things: What’s going on in your head in the midst of a decision, making decisions and then realizing that it was a moment where you could’ve reacted differently [and] that could’ve changed things.

I heard that you mainly record with only a few people in the room.

I don’t do the most, bro. If not that, I’ll record myself. That’s what I did on this album. I recorded a few joints myself. I recorded “What4” myself, slowed it down, and then me and Dom went back and retouched it and added shit, like reversing them parts on the beat. That’s the beginning song of “48,” where I’m singing. I feel like this time was when I learned how to do that and I was confident in doing that. I’m really not a computer-ass nigga like that [laughs]. I honestly like being at the studio, having an engineer.

“What4” reminds me of the intro to Smile, where you’re having a conversation about Trayvon Martin and police brutality.

Mind you, that’s me and VIK talking when we was cutting After Hours, damn near. We was talking about a mall in Rancho called Victoria Gardens. Niggas was doing the most, and I was like, “Damn, this shit is worldwide.” Being a young black man at that time especially and just growing up, you see how people’s psyche be… what be throwing a motherfucker psyche off and making niggas go crazy, bro. It subconsciously affects you, even if you don’t acknowledge it. The fact that I know, as a black man, if I move a little bit wrong, somebody could really project the law in they favor for themselves and crucify me? Even if they know they wrong or lying? Knowing that, you automatically move different.

When I spend time with your music, I start to get familiar with the people you bring up. Even though I don’t know them, I’m listening to the songs wondering about their stories.

Growing up, I used to be at the park a lot. Not on no bullshit, just playing ball, and then just happening to be there all day and seeing everything. I like to think of my shit as just like sitting at the park, park bench raps. From 10 a.m. to 6, just seeing the whole day happen.

That’s the Nas style, you know, just sitting at your window and telling stories.

Nas walk around more than me, though.