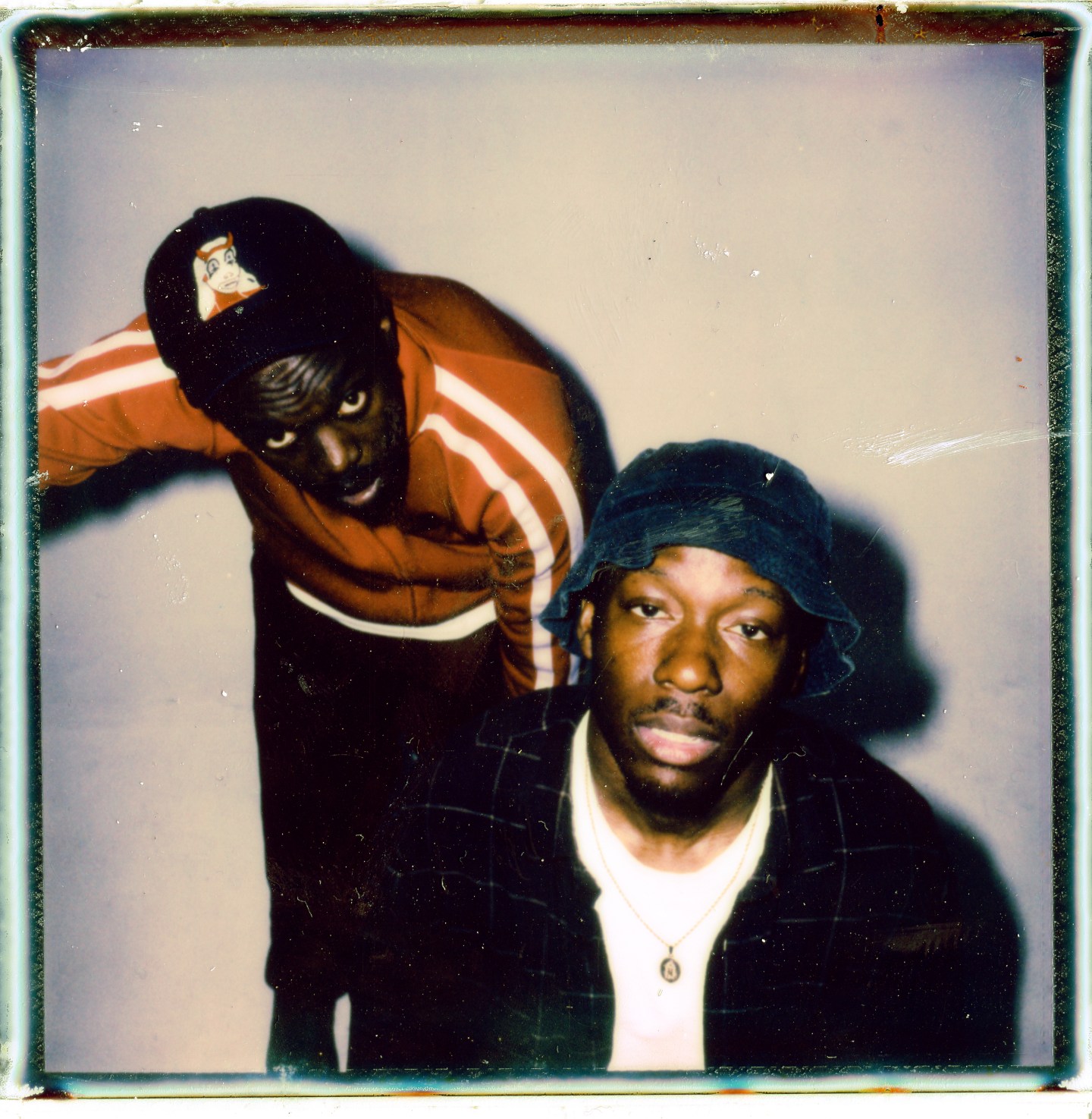

Paris Texas. Photo by Alexis Gross.

Paris Texas. Photo by Alexis Gross.

Paris Texas are fine with being put in a box, as long as they’re the ones closing the lid. In a music scene where genre-blending has become the standard, the duo of California rapper-producers Louie Pastel and Felix are among a handful of acts whose combination of rap and rock feels organic and homegrown, blending together in a cathartic haze of distortion. There’s high concept here too: they approach every project like a movie, complete with its own story board and script.

Both Louie and Felix grew up listening to rap music but took vastly different approaches as they reached their late teens: Felix embraced the then-new frontier of the blog era, while Pastel settled more into the worlds of rock and rock-adjacent sounds. They met for the first time in college and bonded over Florida rapper Robb Bank$ before deciding to work together. It would take a handful of years of live performances and tossing ideas around before they released their debut EP, I’ll Get My Revenge In Hell, in 2018. And the world would have to wait till 2021 to hear what would become their signature sound on “Heavy Metal,” a firecracker single from their debut album, Boy Anonymous.

Mid Air, their new album, is Paris Texas at their most focused and confident. Much of the writing confronts their status as outsiders, their feelings of loneliness, and not fitting into certain perceptions of Blackness. But even at their most thoughtful and reflective, they never fail to come through with the kind of bangers geared to punch holes through concrete. With Mid Air, Paris Texas prove that the runaway success of “Heavy Metal” was no fluke. Their world is one of bold emotion and heavy stepping.

A few days before the release of Mid Air, I talked to the duo about movies, how every Paris Texas project is a timestamp, the pros and cons of the pop-punk revival, artist vs. listener perceptions of their music, and much more.

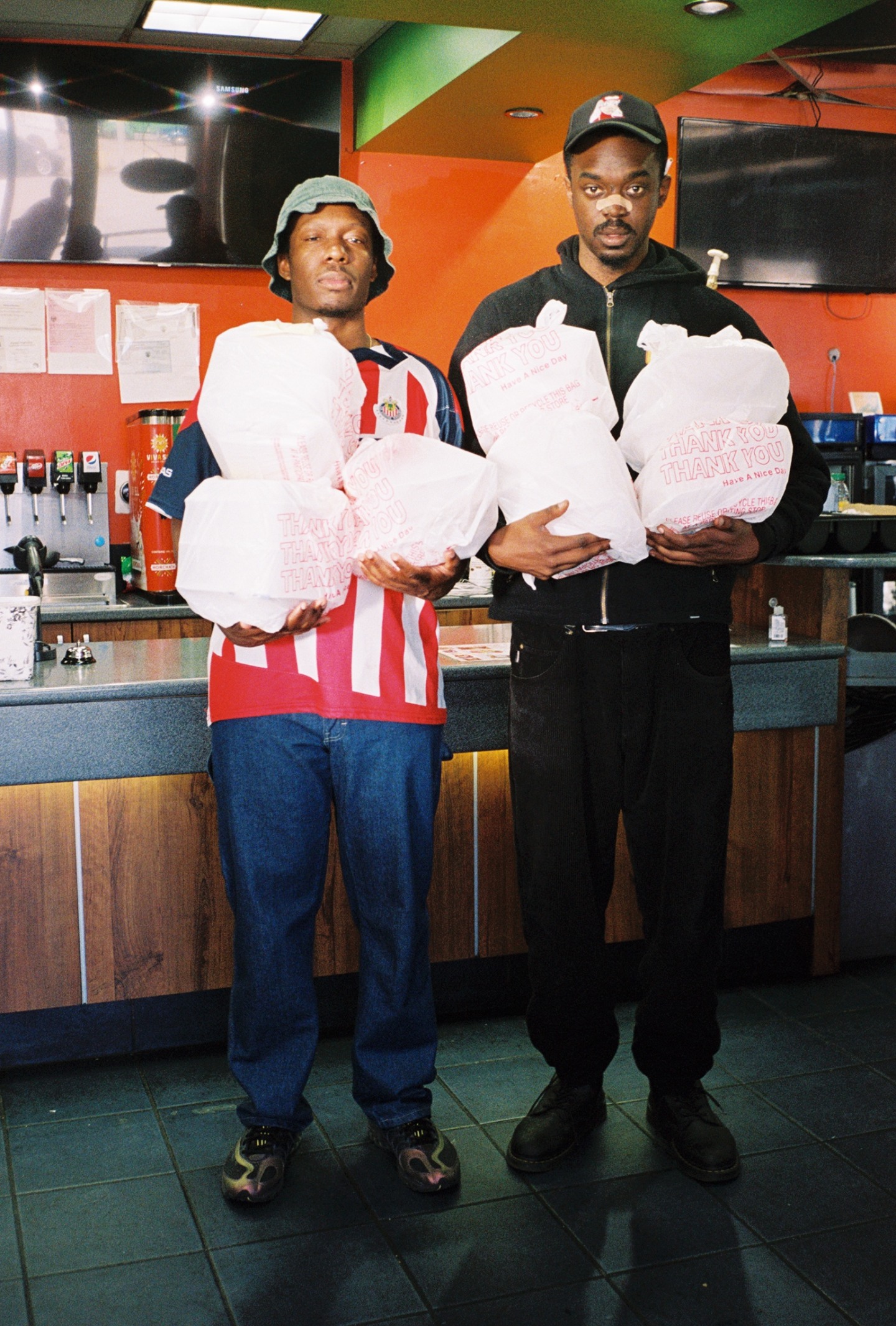

Photo by Saru Hager.

Photo by Saru Hager.

This Q&A is taken from the latest episode of The FADER Interview podcast. To hear this week’s show in full, and to access the podcast’s archive, click here.

The FADER: When did y’all first see the movie Paris, Texas?

Louie Pastel: Way after we named ourselves that. He still hasn’t seen it.

Felix: Yeah, I still haven’t seen it.

Damn, OK. So what did you think of it?

LP: The name is hard, so people gravitate towards it. I’m a cinephile, but I’m also not pretentious. That’s the one you can bring up and get everybody’s ears horny — “Oh, the cinematography!” — but the story is kinda bland to me. There’s certain white movies that are cool when they go through their weird little existential shit. That one’s not one of them.

How did y’all settle on the name Paris Texas, then, outside of the fact that it sounded hard?

F: It was about both places, respectively, being polar opposites. That worked for us in terms of how [we] grew up and the music we make and our interests, juxtaposed to what the norm is. Nobody is doing it how we’re doing it, at least that I know of.

I can’t think of a lot of songs that sound like “Bullet Man” right now.

LP: People still sleep, man. I thought that was gonna be our biggest song, and everybody’s like, “No, we like ‘Panic.’” Man, suck my dick.

Songs are sleeper hits sometimes.

F: The singles damn near are the sleepers. I guess it’s a good problem to have, but it’s crazy.

LP: The singles remind me of what happened before To Pimp A Butterfly. You’re like, “What the fuck are we getting ourselves into?” Coming off of Good Kid, M.A.A.D City and “Control,” [you get “i”] and you’re like, “I don’t know if I’m gonna like this shit.”

“I’m not gonna be a Black dude who perms his hair and wears Naruto shit.”

Take me back to before the two of you met. When did music come into each of your lives as capital-M Music?

LP: I was probably mad young. Being Black, it’s just a part of you.

F: I think the timeframe when [I decided] I’m gonna try was College Dropout. But [I] always used to just sit up and watch MTV all day — Missy videos, Gorillaz videos. When do you think [you] was like, “Alright, I’m gonna try?”

LP: When I was 15, I was dabbling, like, “Oh, this my hobby.” When I was 19, I was like, “OK, I fuck with this a little more than I’m admitting,” because I didn’t wanna be a musician [at first]. That was not my dream.

And then y’all were introduced in 2013 by a mutual friend who got you into Robb Bank$?

LP: We knew about [Robb Bank$] separately. I’d started listening to rap again — I wasn’t for a long time. I was talking to my friends, like, “Yo, what do you think about Robb Bank$?” Everybody’s like, “This is ass,” and I’m like, “What’s going on? I feel like this is fire.” It was his first mixtape I was running back and learning a lot from. We were just the same age, Robb and I, so [it felt] like a cool perspective. When I was talking to Felix, he was like, No, this shit tight.” I’m like, “Okay, so I’m not trippin’.” He started exposing me to more shit, and we’d go back and forth.

The two of you had wildly different relationships to rap music at that time. Louie, you were into math rock and post-hardcore shit. Felix, you were into the blog era and super tapped in. When did y’all first decide that rap was the end goal?

LP: It was before I met him, actually, that I started dabbling more into rap. A lot of music I was into during a certain era, I could see it was dying. I was also like, “I’m Black.” Trying to go into those spaces was way harder than anybody could possibly imagine, especially back then. It was, “Okay, I’m from Compton. No one around me is listening to this music. No one around me is even in a band.” And I wouldn’t put on the costume. When you’d go to Warped Tour back then, they’d expect you to put on the costume. I’m not gonna be a Black dude who perms his hair and wears Naruto shit.

I went to high school with two kids who were about the screamo, and I really looked up to them. I remember them doing a talent show: They just went on stage and started screaming and doing heavy shit. But I was like, “I’m good on that. Shout out to y’all for being brave… Hell no.”

When I got out of high school, I just liked doing this thing. I wasn’t chasing it for any type of notoriety. I just really like movies and creating a storyline. When I came to Felix with ideas, there was always a script on the side: “We’re gonna do this project, and we’re gonna have a short film on the side of it.” It’s always been a goal to do the film stuff over the music stuff, and rap was the easiest way.

Photo by Aus Taylor.

Photo by Aus Taylor.

How did everything that you just said apply to the making of your first project, I’ll Get My Revenge in Hell?

LP: People were waiting too long. We had a lot of friends who were supporting us, and it was so long where we just performed with nothing out, and people were like, “What’s your SoundCloud?” So Revenge was us being like, “Alright, we’ve gotta put all this out.”

F: It was the status update of where the music was at the time.

Looking back on that project five years later, how do you feel about it?

F: I haven’t even listened to that project in full. I remember everything that’s on it; I just haven’t listened to it sound wise, to see the growth over time. You could tell the resources were so much smaller. That’s all Louie on a computer keyboard. Any piano or other instrument was digital.

LP: Revenge was such a training thing. I’m mad ego driven, so I’ll always read what forums and weird little discords are saying about us. People will be like, “You could tell this is just blah, blah, blah.” It’s like, “Bro, we were just trying shit.” We only kept it up because it’s proof that we existed before Boy Anonymous, so people [don’t] think we just came out of nowhere and got fed into the industry. Listen to this project. If you think it’s ass, what the fuck ever. But you need to know we existed before.

What’s your next steps between Revenge and Boy Anonymous?

LP: Boy anonymous was really [made in] 2019, a couple months after Revenge. The original game plan wasn’t what came out, just what we were able to do at the time. There’s still a lot of things with Boy Anonymous that I wish we could go back and redo or add to.vThere’s a lot of maturity from the three projects, going from Revenge to Mid Air. We’re saying stuff without saying stuff. There’s snippets of shit, but you can hear we’re practicing, going into different areas and getting more comfortable trying shit out.

“Nothing’s worse than people already having your trajectory in mind.”

LP: I’ll be real with you: it kinda sucked. It was tight, but it felt weird at the time, because people immediately tried to put it into a box. I don’t even mind [being put in] a box if it’s the right box. If somebody’s like, “Here’s the box that gets a bunch of hoes and a lot of money,” I fuck with that box. I’m not mad about that box.

But people were like, “Blank, blank, blank! It’s blank! It’s blank!” But it’s really not those things. You’ve gotta really peel back the layers. There’s a lot of people who were in a certain fan base that were really gatekeepy and weird about our music. So it spread, but it spread among the artists in the industry, and there was a weird reset where people were like, “Oh, finally, this type of art again.” There was an invisible torch that got passed to us, but it sucks because we’re not really those things. I don’t want to say any names, but nothing’s worse than people already having your trajectory in mind.

Tell me about the evolution from Boy Anonymous to Red Hand Akimbo to Mid Air: how you fine-tuned what you wanted to say, and how you wanted to say it, and the way the sounds came out.

It was a part of myself that I was pushing down for a long time. Every time I would show people the type of music I was into before rap, it was so looked down upon. People wear it on their sleeves now that they fuck with it, but [they’re] fucking with it because it looks cool to be the Black person that’s not a monolith among everybody else. You’ll get an interview, like, “What’d you listen to?” “Paramore and Panic! at the Disco.” “No shit. Everybody heard that. It was pop music, dickhead. It’s like a white person being like, “I know who Drake is.”

Pop-punk revival… Let’s be very real: It’s tight and I fuck with it still. But that type of music died for a very specific reason. The reason why people in the last couple years have been able to really do it right — Trippie and Juice and X — was because they were doing it over hip-hop beats. That’s what made it special: they formed a new instrument. They used 808s and all these things that you use usually for hip-hop, and they made it something different. I’m not gonna do that because they’ve already done it. I’m not gonna be a pop punk guy because that’s just corny. I’m just gonna do it the way I know how to do it. One day I’ll have a book, and people will know where I pull from. Usually, people are wrong as shit.

Felix, once that sound started to take off, how did you feel about going in that direction?

F: We knew what the landscape was for that sound, and I was like, “Man, I hope n***as don’t think it stops here. Obviously there’s a lot of influence from that genre, but it’s what people were choosing to hear — the foreground of the background. Most people who listen to music listen to the soundscape, but even then, there’s much more going on than just the guitar.

I was hoping both sides would get equal treatment, but it never works that way. You lean into one more than the other. And over time, people will see the way you bleed them together. I’m curious how the world’s gonna think about [Mid Air] now.

You’re really digging into your lives on Mid Air. There are allusions to getting over feelings of loneliness, not fitting into a certain Blackness, a sense of stasis where you’re like, “Where do I belong? I’m gonna make my own space.” What does the idea of “mid air” mean to y’all

LP: It was none of those things. I thought the name sounded cool originally, and then my manager was like, “That makes sense, though, because you guys are in between. You took off, but you don’t know if you’re gonna go any higher or fall.” So this project is that: It’s all over the place. There’s no real meaning behind any of it. There’s two of us, so sometimes it’s hard to lyrically align because we’re such different people, even though we’re the same. We’re saying as much as we can from both sides and letting people know. It’s just another status update.

The FADER: The “Bullet Man” video is really maybe the coolest I’ve seen all year. Where did the idea come from, and how do you feel it fits in with the song itself?

LP: We were meeting with some director and I had an original idea, and he was like, “I don’t wanna do that because I hate violence without a point.” That was the birth of “Bullet Man”: I was like, “Okay, dickhead. I got you. Let’s take this gun-barred song and put it over rock instruments and then put it into this video.”

It’s a rap-rock beat, which is usually white, and then us rapping like we’re NBA YoungBoy or some shit. That’s the same concept as the video, where it’s this white kid who thinks he’s Black and the dad [is] upset, thinking Black culture is taking over.

They love looking at our situation and love playing it to the nth degree, being fans. Trap Lore Ross is a thing. It’s like, “Alright, let’s take your genre that you love so much. Let’s see what happens if [we] talk about you guys’ weird ass shit. Hell’s Angels does not have an artist under their name, but every gang we have does. There’s no Nazi rockstar — let’s go ahead and put that at the forefront right now.

Photo by Alexis Gross.

Photo by Alexis Gross.

The thing I love about this project is that it feels so definitive: “You can’t tell us who we are. You can’t tell us what it means to be Black. We’re Black. We do this.” What do you feel is the biggest difference between y’all as artists when you first start making music together and now?

LP: All the ingredients were always there; it was just knowing how to put it together. We were always this good, as hard as it sounds. Whatever you see right now, it’s what what we’ve always been capable of. It’s just being able to use other people’s ingredients, because that’s the one thing we didn’t have for a long time. We weren’t really asking for help, and now we know how to ask for help.

F: I’ve stripped back a lot more than I used to. I’ve learned about quality over quantity. There’s a certain time and space to do as much as you can, especially in writing verses. I’ve taken a different approach to listening to music, and it’s helped me understand more of the context. It’s always funny looking back on the old shit.