My first real look at Jack White when I arrived in Detroit was, really, no kind of look at all. Out there in some office-park nether-exit off I-696, I stepped into the hallway adjacent to the White Stripes’ photo shoot. There, 20 feet away or so, an immense figure strode away from me in blood red pants—snug and straight—and a black button down shirt—untucked; he had a walking cane, a top hat and his head held high as dark strings of black hair streamed down around his neck and shoulders.

An hour or so later, I walked into a bar directly across Woodward Ave from the Magic Stick, the downtown Detroit club where the White Stripes used to play (and where Jack famously whupped that dude from the Von Bondies in December of 2003). Slightly bored, Jack sat alone in a booth in the back, looking infinitely less mythical (though now even more explicitly broad and strong) in a white undershirt, tightly tucked-in. He quickly excused himself to grab Meg White, who sat on a stool at the bar, smoking wistfully over a pint of Labatt’s.

The last time I had seen the White Stripes was in November of 2003 after the release of their fourth album Elephant, when the steady squall of noise that first surrounded them in 2001 was reaching new heights. They were no longer an emergent band with a constructed image and funny faux-sibling banter—by then, all of us in the crowd were so familiar with the red, white and black that we almost forgot to notice it. Instead we were there to see if they’d play “Hello Operator” or “The Big Three Killed My Baby”; to see what Delta bluesman or golden-era country star they’d cove.

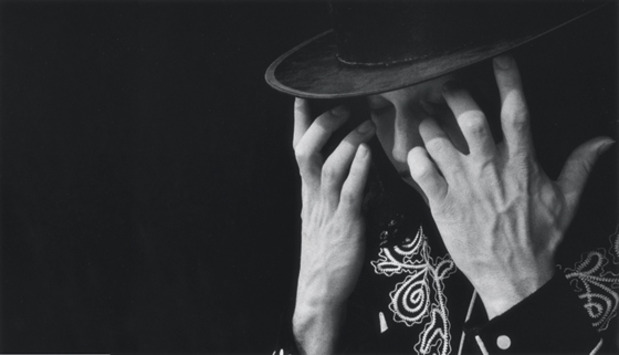

The show was in one of those concert halls that makes you feel like you’re watching people watch a concert, and Jack White struck an imposing figure. He looked ten, twelve, fourteen feet tall up there, his shoulders robust and his guitar a mere lash—a prop that he abused while projecting massive amounts of sound like lightening bolts from the rest of his physique. Meg, meanwhile, sat behind the drums, all chest and swinging hair and head tucked alternately behind this shoulder or that because she’d almost certainly be smote by one of Jack’s flying bolts if she put it anywhere else. The show wasn’t just good—it was long and intense and menacing and so packed that there was a weird sense of community. Maybe it was because having the White Stripes in town was our little taste of eras past, when the monsters of rock had private jets so they could come play a sports stadium near you.

After the Stripes’ world tour in support of Elephant, the band took more than a year off to rest and weather the backlash that would inevitably follow the record’s overwhelming success (over four million in worldwide sales). Meg disappeared, but Jack stayed busy. He appeared in the Civil War movie Cold Mountain and recorded songs for the soundtrack. He played guitar on and produced Van Lear Rose, a Grammy-winning record for Loretta Lynn. He and Meg appeared in Jim Jarmusch’s film Coffee And Cigarettes, and he recorded a yet-to-be-released album with his neighbor Brendan Benson. Then, finally, he and Meg reconvened in March to record their fifth album Get Behind Me Satan. It took less than two weeks to complete.

Ask Jack White a question, and his eyes darken as he looks at you intently—he holds your eyes and furrows his brow, nodding along to show that he’s with you. Then when you’re done, he talks fast, in a flurry of confidence and ideas. He’s not angry, but he speaks from a place of anger—it’s the dominant emotion of his worldview, not the particular emotion he’s feeling when he says, “In America, culture is so dying that towns don’t have much of their own culture and when they do they latch onto it because they’re so proud of it.” White sweeps his hair out of his face and continues. “But nothing’s gonna last. Now somebody finds out about it—or with the internet, everybody finds out about it—and it becomes commoditized and people throw tons of money at it. A few people make tons of money and then no one cares. That’s not what was happening to Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly. They weren’t getting offers like that.” He pauses, then adds, “They were getting ripped off.”

White is relentlessly nostalgic, and it’s clear from his tone that, ripped off or not, he envies Guthrie and Leadbelly. Elsewhere in our conversation he even suggests that he longs for the 1920s because musicians performed on street corners. The White Stripes just performed at a series of soccer stadiums in Central and South America because they’d never been before and wanted to go and had a shitload of fans eager to receive them, but here’s Jack suggesting that he’d rather be Curtis Lowe, playing a dobro for a fifth of drinking wine.

To be fair—street corners or not—the White Stripes paid their dues. “We spent so much time in broken down vans, selling 45s at our shows,” Jack remembers. “It’s about nobody caring and that forces you to care only for the right reasons. You know, we didn’t hit until our third independent album [White Blood Cells], but if that had happened with our first album White Stripes, it probably would have been the kiss of death.”

Perhaps the most valiant thing about the White Stripes is the example they’ve set for other artists. By being the undisputed Most Precious Band In America, the Stripes have stayed out of the gnashing teeth of the huge mechanical beast that has hovered over them since 2002, when their Lego-animation video for “Fell In Love With A Girl” took off on MTV. Since then, Jack has fought tooth and nail to maintain the Stripes’ dignity, their privacy and their values, mostly by knowing how to say “no.”

“It’s almost dangerous to do anything these days in the public eye,” he says. “There’s just so much opportunity to blow it. I spend so much time protecting our band from interviews and photo shoots because it’s too much work to have your guard up all the time. There are so many opportunities thrown at you that would not have been thrown at a band 20 years ago. If we wanted to, we could spend three million dollars and nine months working on an album. It’s just absurd.”

A couple weeks before flying out to Detroit to interview the White Stripes, I watched Under Blackpool Lights, the live DVD that the band released last year. The film is wholly representative of the band’s carefully controlled aesthetic: there are songs written by the old and the dead from Dylan to Hank to Leadbelly. It was shot on hand-held Super 8 cameras. And it was filmed in Blackpool, England, a beachside town famous for its “illuminations” that was once the retreat for Britons until jet planes started whisking them off to the warmth of Thailand, New Zealand and Disneyworld. The town is now a tourist-mongering shadow of its former self—a paradise lost, and the perfect setting for the White Stripes’ gothic blues.

At one point in the film, Jack stops to address his audience, calling out to them, “Blackpool lights!” He’s come down from the thrashing energy of the previous song and suddenly, as he parts his hair from his eyes, his presence is very, very grave. “I heard George Harrison say the Beatles used to go see Blackpool lights—what is that?”

“That’s the lights of Blackpool,” someone calls out from the crowd.

“A different place altogether?”

(“Yeah!”)

“I’m in the right place at the wrong time?”

(“YEAH!!!”)

Almost seething now, Jack spits out, “That’s how I feel every day,” then abruptly leaps backward and into the intro of a desperate, soul-clawing cover of Dolly Parton’s 1973 song “Jolene”.

My own relationship to the Stripes has always been conflicted—Jack White has consistently made some of the most forward-thinking music of the past seven years, but his over-idealized nostalgia for the past and unhinged disdain for the present is endlessly frustrating. At no point in our interview does he ever express any hope for the future. And didn’t he just tell those adoring fans at Blackpool he wished he wasn’t there with them—before launching into a near-perfect re-imagining of “Jolene” that must have overwhelmed them with the thrill of being right there, right then? The song is so soulful, so genuine, so desperate, that its power even comes across on a damn DVD. Jack might say something like, “People don’t write songs like that anymore,” but the whole point is that he does.

The White Stripes’ fifth album Get Behind Me Satan is their first realization of the scope of Jack’s “general idea that all music is the blues,” as he puts it. From the beginning, the Stripes have incorporated touches of various forms into their sound, but their bread and butter has always been explicitly derived from the Delta tradition—a distorted re-imagining of the chords and rhythms of Robert Johnson, Charley Patton, and Son House. On Satan, however, they’ve distributed the weight more or less equally across a broad range of styles, all of which have, as White suggests, the blues as their foundation. “One of the goals of the band has always been just to see how much two people can do,” he says. “There’s bluegrass and blues and rock & roll and dance and gospel, and they’re all coming out in different directions.” There’s also metal, soul, punk, pop, country and beyond.

Although Jack White is probably the best of the handful of players in his musical generation that still use the guitar to play explosive, free-wheeling riffs and leads rather than just chords for texture, Satan is not a record for the guitar store geeks. White only flashes his electric blues brilliance on two songs, and there are only a clutch of riffs on the record. Instead, he turns to songwriting and his acoustic guitar, and even more effectively, to his piano. He’s also expanded the sounds at the band’s fingertips with the simple addition of a marimba. White pushed the instrument to the front of the album’s mix, and the plucky melodies he summons from it trade some of the Stripes’ corn-fed guitar-n-drums earthiness for some surprisingly mysterious, almost other-worldly airs.

Lyrically, the songs remain largely about love, and the specter of Rita Hayworth haunts Jack’s characters throughout like a sexy, pesky muse. She’s only mentioned explicitly in two songs, but she could easily be the inexplicit “she” on almost every track. Few are love songs, but almost all are about longing for love and the push and pull of relationships; about being together, about being apart, about being lonely, vengeful, jealous or betrayed. White navigates the terrain with his characteristic and self-perpetuating combination of anger and moral absolutism, singing, “If there is a lie, then there is a liar too/ If there is a sin, then there is a sinner too.”

White has said that red represents anger, white represents innocence and black represents death, and, of course, there are no other colors in the White Stripes’ rainbow. So rather than expanding his range of emotions, Jack has dug deeper into the dormant possibilities within those three subjects. What he finds are new moods, nuances, modes and inflections to project, all the while sticking to his amazingly expressive nursery rhyme schemes. The album closer “I’m Lonely (But I Ain’t That Lonely Yet)” is a straightforward country-soul-’n’-gospel ballad on the piano, and Jack almost whispers the third verse: I went down to the river filled with regret/ Looked down and I wondered if there was any reason left/ I left just before my lungs could get wet/ I’m lonely but I ain’t that lonely yet...

When Jack White calls quick success a “kiss of death,” he pinpoints the fact that we—our culture—don’t want our heroes to turn out to be survivors. We take our self-made men and women and throw at them way more than they can handle, not for the pleasure of knocking them down, but for the infinitely more enjoyable spectacle of watching them self-destruct. Yet no matter how much the White Stripes accomplish, Jack has preempted the built-in danger of success by defiantly maintaining that he’s the underdog—someone who’s never quite the man he wants to be. It’s there in the piano ballad “White Moon”, where from the perspective of a GI longing for his pin-up girl Rita Hayworth, Jack sings, “Good Lord, good Lord/ The one I adore/ that I cannot afford/ Is a ghost,” and it’s there in the album title: Get Behind Me Satan assumes that the devil’s out in front and there’s a lot of fighting left to be done. White’s anger, his talent, his tireless drive, his disdain for modernity—all of it results from his understanding of his own inadequacy; his own inability to have a world as perfectly-constructed as the make-believe world of his band.

Ask him specifically what it is about the past that inspires his starry-eyed nostalgia and White raps his fist on the table in frustration and falters in search of the words. “It’s hard to define, you know,” he says hesitantly while gazing off towards some imagined horizon and still mashing his fist down intensely. “But it’s something to do with… It’s something about romance and something about beauty.” White always sounds like a stubborn pessimist, but in the moment he seems like our great optimist—someone who refuses to believe that there can’t be more romance and beauty in the world, and someone strong enough to hoist that cross on his back to see how far he can take it. Annoying as his nostalgia may be, White first defined a cultural moment by being the kind of person they don’t really make anymore—an intellectual with a right hook; an artist with impact, not just talk; a man with enough wit for sarcasm but enough honor to choose sincerity instead. At one point on Get Behind Me Satan, White sings, “Can it be that I don’t want what you want?” It is, undoubtedly, a rhetorical question.