Three rising artists discuss how growing up in the ’90s has affected them, and how it hasn't

From the magazine: ISSUE 90, Feb/March 2014

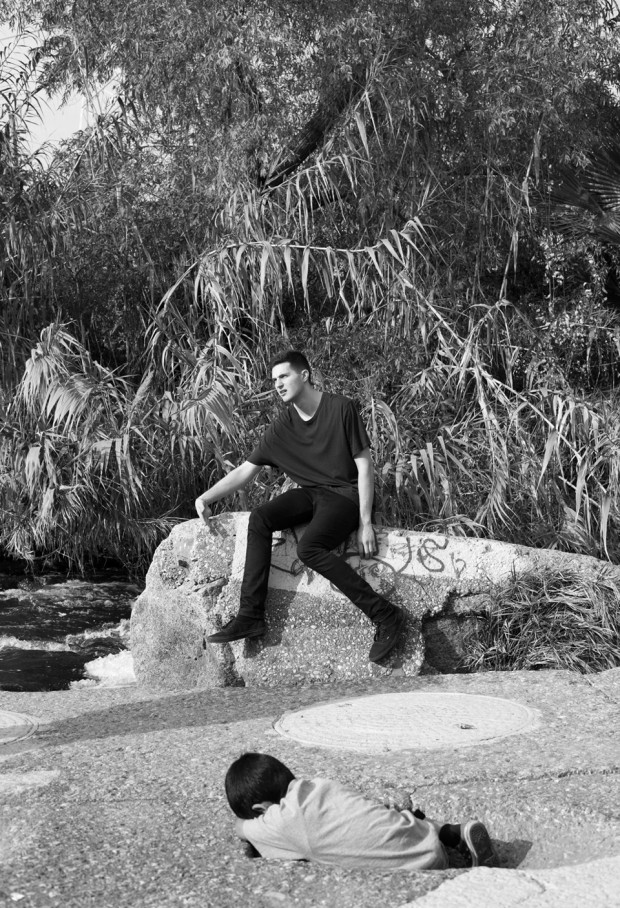

YG

Over the past half-decade, 23-year-old YG has proven himself a consistent maker of jams. Like NWA, Snoop and DJ Quik before him, YG is from Compton, and the sound of Los Angeles hip-hop lives through him and his longtime collaborator DJ Mustard: crisp drums, loud raps and a predilection for party music. His debut album, My Krazy Life, seeks to rein the looseness of his signature songs “Toot It and Boot It” and “My Nigga” into a single narrative, chronicling a day in the life of a young man in California. He explained his history and how the time and place of his early life did—and didn’t—affect where he is now.

—matthew schnipper

YG: I was born in ’90. I don’t remember when the Rodney King riots were going on. I was younger than a motherfucker. And Pac died in ’96—I really don’t remember that. I can’t even go back in time and tell you when I was six what was going on, because I can’t visualize that. But I know I was somewhere around here, going to school, fucking up. Growing up in the ’90s influenced my lifestyle a lot, because I was going to a lot of house parties, and the music they was playing was like DJ Quik, Suga Free, Snoop Dogg, Dogg Pound, Dr. Dre, you feel me? All the West Coast music. That was the music we was partying to coming up. That was the music my mom and my pops was listening to coming up, so that was the music I was listening to when I didn’t really know what the fuck music was. That really shaped my lifestyle, the lifestyle I chose to live—gangbanging, being in the streets, robbing shit, hustling—I know some of that came from music I was listening to.

Growing up, I would go home from school, record some music, upload it on Myspace, and then back over at school, the motherfuckers was playing the record! I had this movement, and we was really in the streets, doing shows, doing all the house parties. We was smoking weed, drinking, fucking bitches, doing that whole shit. We was breaking into houses, we was robbing people, we was robbing stores, we was doing all this crazy shit. Then I caught a case in ’08, like, in September, and I had to go to jail. My mama bailed me out like a month and a half later. And then I had to turn myself in like the next year in March. I sat down, I did some time, got out, and three months later I got a record deal. So that’s when I got signed to Def Jam.

The way that I got to where I am today is because I started investing my own money in myself and records I believe in. I was shooting my videos, paying for this shit out of my pocket, basically from the money from doing shows, sending my videos out on YouTube and getting them on WorldStar. Then [after touring with Snoop, Wiz Khalifa and Tyga] I headlined my own tour. So I’ve been on a roll for like three full years of just doing the same shit, the same cycle. And I was doing my homework. I was just doing a lot of research, paying attention, listening to a lot of albums, listening to a lot of productions up in the studio, going hard—all that.

My music sounds like what it looks like. We come from the Los Angeles County. I’m from Compton, DJ Mustard’s from LA—we grew up doing damn near everything you can do out here. It’s really the lifestyle; like, I want my album to be an album where motherfuckers wake up and live their life to my shit. I want motherfuckers to party to my shit, I want motherfuckers to have fun to my shit. That’s what I’m going for for my album, but at the same time, the concept behind it is not just like, “party, turn up, have fun.” It’s a story, a movie and shit, and it’s real life situations that I been through. And I’m sharing with you.

Tinashe

Tinashe Kachingwe takes pride in producing, recording and self-releasing her own songs, but unlike most of her peers seeking R&B stardom through free mixtapes, at 21, she is already a credible industry veteran. And not just with music: Tinashe has acted in movies (Akeelah and the Bee), recorded voiceovers for animated films (The Polar Express) and been on TV (Two and a Half Men), in addition to opening 20 shows for Justin Bieber as part of the since-disbanded six-piece The Stunners. She’s an artist of many mediums—can you tell she was born in the ’90s? But it’s her solo music that caught our ear (and recently landed her a deal with RCA), and it’s her inclination to work both sides of the recording booth that’s won our respect. From her home in LA, Tinashe spoke about growing up a performer, doing interviews in the Twitter era and why, whether you’re signed to a major or seeking a deal, there’s nothing like doing it yourself.

—duncan cooper

Tinashe: My dad was born in Zimbabwe, and my mom is from Iowa. My earliest memories are singing songs in the household, either with my family or performing for them. It was just a big part of my day-to-day. My parents played a lot of Sade, Michael Jackson, Janet Jackson, Tony! Toni! Toné!, Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, and I kind of learned by mimicking what they were doing. From when I was like, one year old, my parents realized I had a huge passion for putting on a show. I started dancing when I was four, and I was in my first movie when I was five, but I never felt like my parents were pushing me in any particular direction. They were just there to support me.

The first artist I was a big fan of that my parents didn’t introduce me to was Christina Aguilera. She was the first concert I went to, and vocally, she was a big influence. I was young at the time—probably seven—and she was still a teenager, just a kid who could out-sing her competition. A few years later, I rediscovered Janet, and I got to listen to some of her albums that were older than the ones my parents had played when I was little. I’d watch all her concert DVDs, try to learn the choreography. It was very exciting to feel like you could dig up all this research on somebody.

In the digital age, things in the music industry have changed really quickly in a short period of time. Even the concept of interviews is different now. Most of the questions I get asked by journalists have already been asked on Twitter and Facebook 100,000 times, and my fans all know the answers. But that does open doors for new ways of doing things, and hopefully it’ll spark artists to be more creative with how they put out information. I just don’t want to be put in a box. I want to have the ability to grow and evolve.

Record labels don’t necessarily have the formula in black-and-white anymore. I can just look at my peers and obviously see that no one is going in stores and buying music. I realized that, hey, it’s probably more valuable for more people to hear my music than for me to sell it. For the free mixtapes that I put out, the label basically wasn’t involved at all. I either made the beats myself, found people I knew through social media or literally crowd-sourced production. I recorded it myself, I mixed it myself. I don’t think it’s essential to do that, because there’s so many professionals who’re paid to do those jobs, but I think it’s incredibly, incredibly advantageous. It’s so much faster: my last three projects were only put out because I was able to create the music myself, and I wasn’t limited by waiting for someone to do something for me. It’s just so easy to go on YouTube and learn to do anything. Why not know how to produce, why not know how to mix, why not know how to record when it’s so simple to do it yourself?

I just started making beats on my friend’s computer after school, an older Mac, pirated my own software, and thought, Oh, I like doing this. —Jim-E Stack

Jim-E Stack

Jim-E Stack is a producer from San Francisco who, at only 22, has developed a signature sound of buzzing synthesizers and wobbly, hand-clapped tempos that lives somewhere on the grid between dance music and something too weird to move to. His music ping-pongs around in your brain in a manner that feels precocious for a self-taught artist his age, but it also recalls the chaotic pulse of the city he grew up in. He told us how the genre-mixing of both his childhood neighborhood and his iTunes playlist has shaped his outlook on art and life.

—alex frank

Jim-E Stack: I grew up in San Francisco. Just right in the city—Inner Richmond, near Clements Street. My mom’s house is less than a block away from Golden Gate Park. San Francisco is different now: the tech bubble is just this huge bubble of redevelopment and gentrification. But growing up in the city [when I did] meant exposure to different cultures. Our area used to be heavily Chinese and Russian immigrants; I’ve never lived out in the suburbs, but I don’t think that exists there. It’s different now, because everyone from fucking Google lives there. And it’s too clean—it’s kind of this perfect little place. It’s good for the city, all that tech stuff, but it’s also losing so much of what makes it “it.”

I started to play drums when I was 11. I was just listening to like Blink-182 and whatever an 11-year-old would listen to. In high school, I had a core group of friends I played music with and they were very much into San Francisco punk and garage kind of stuff. Those friends put me on to Hüsker Dü and rock-ish stuff, like Sonic Youth. But I think what was cool was that we listened to every kind of genre. Hanging out in the park and stuff on the weekends, kids would be listening to a Clash record and Lil Wayne back-to-back. Why would that be weird? I feel like any other generation—I don’t even know what there was in the ’80s, like hair metal?—you wouldn’t listen to two things back-to-back like that. Jim-E Stack is just an amalgamation of everything I like.

I just started making beats on my friend’s computer after school, an older Mac, pirated my own software, and thought, Oh, I like doing this. I guess my beats were some collision of rap and grime, like a hip-hop instrumental and a grime instrumental—but just really, really terrible. I was doing whatever came into mind. That’s kind of the beauty of it: there was no vision whatsoever. It’s just trying to make some shit. What’s embarrassing about this generation is that I probably had some stupid-ass Myspace page for just making my beats in high school, and you can find it. I don’t have any regrets, but when you’re in that teen period, every year you move forward and then look back at yourself on Facebook, you think, God I was such an idiot. Every year of your life, the year before, you were such a dumbass.

I’m in Brooklyn now, taking some classes, and I know there are artists that have some barn or whatever they work out of in upstate New York, but for me, so much of being creative is just having that urban environment to be inspired by. It’s kind of daunting knowing that some of these cities are getting more expensive—I guess it’s a worry in the back of my mind, just because there’s no way I could not live in the city. But that model of, get good grades in high school, get into college, get a good job, support a family—that model is gone. Especially when tuitions are so insane and there really aren’t the jobs out there that there used to be, it’s kind of up to you to figure your shit out for yourself and not just rely on this kind of societal norm of a life path. But I think that’s a blessing and a curse for ’90s babies—having to figure it out on your own is more stressful. But since college doesn’t guar-antee you shit anymore, you might as well do something you really care about. And I don’t know what else I could do in life except music.