Meet the Photographer Who Documented the Skinhead Scene: “I’m a cocky fucker.”

Photographer Gavin Watson on Dr. Marten’s new collection and the working-class uniform’s lasting appeal.

From the magazine: ISSUE 94, on stands October 21st. Pre-order a copy here.

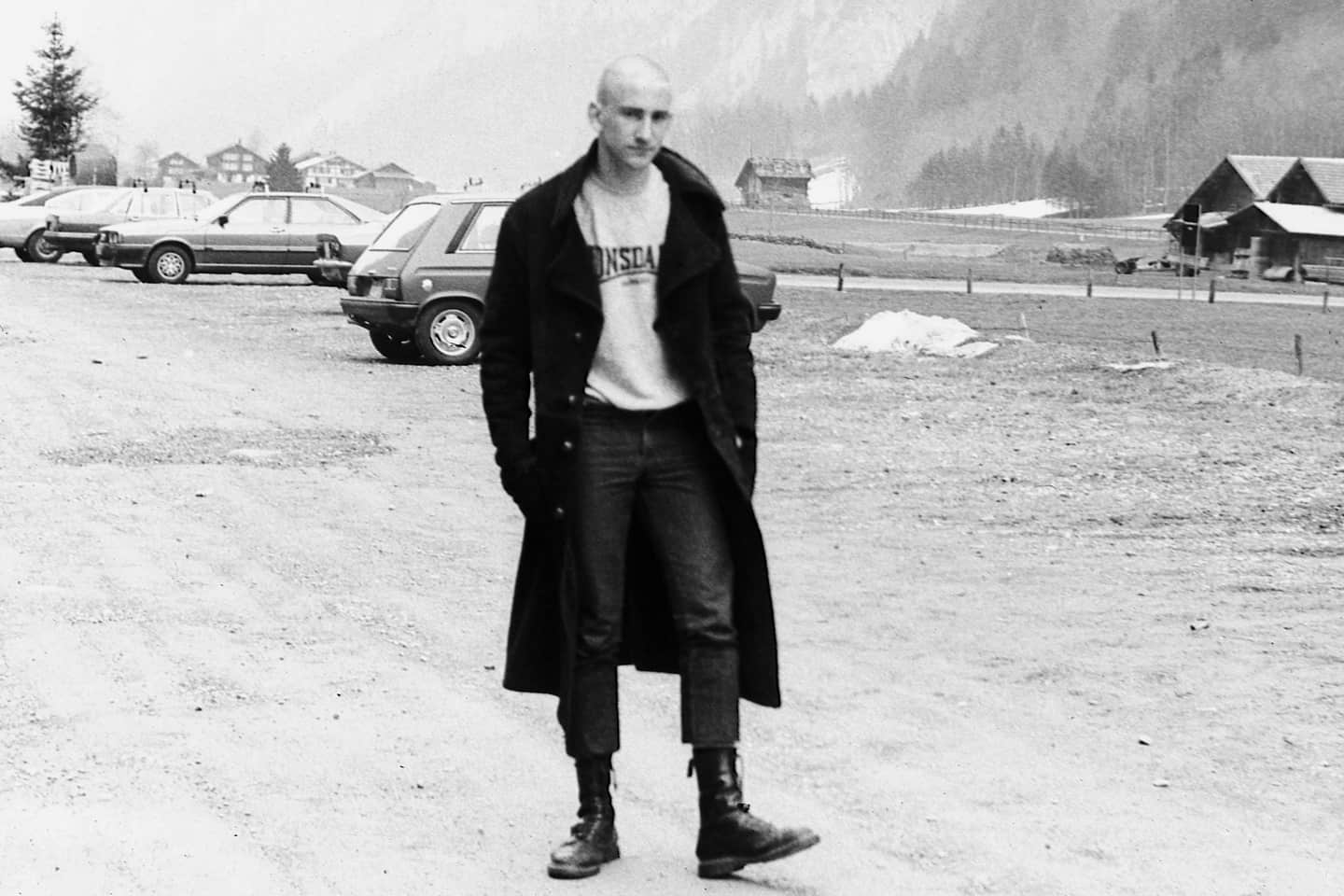

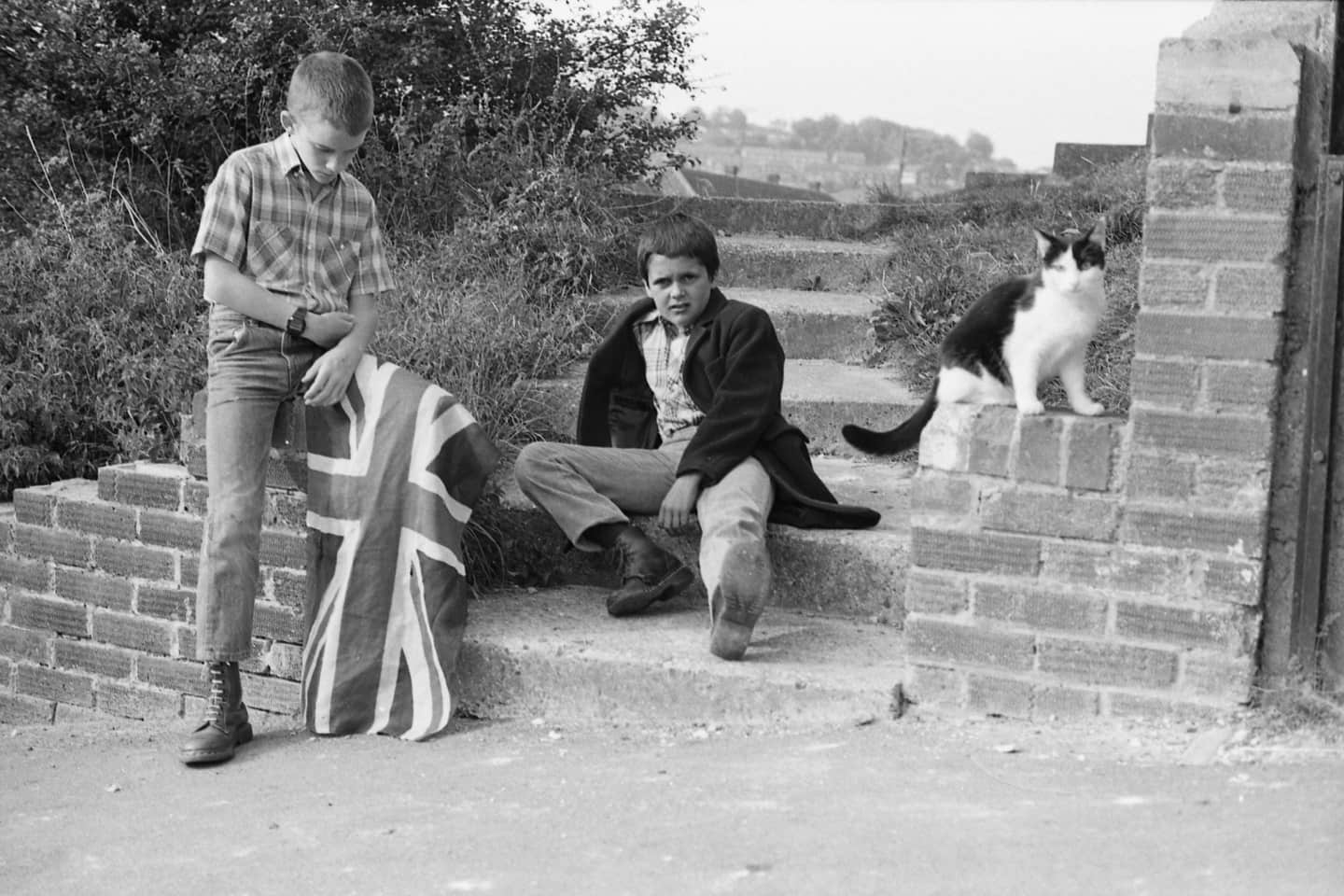

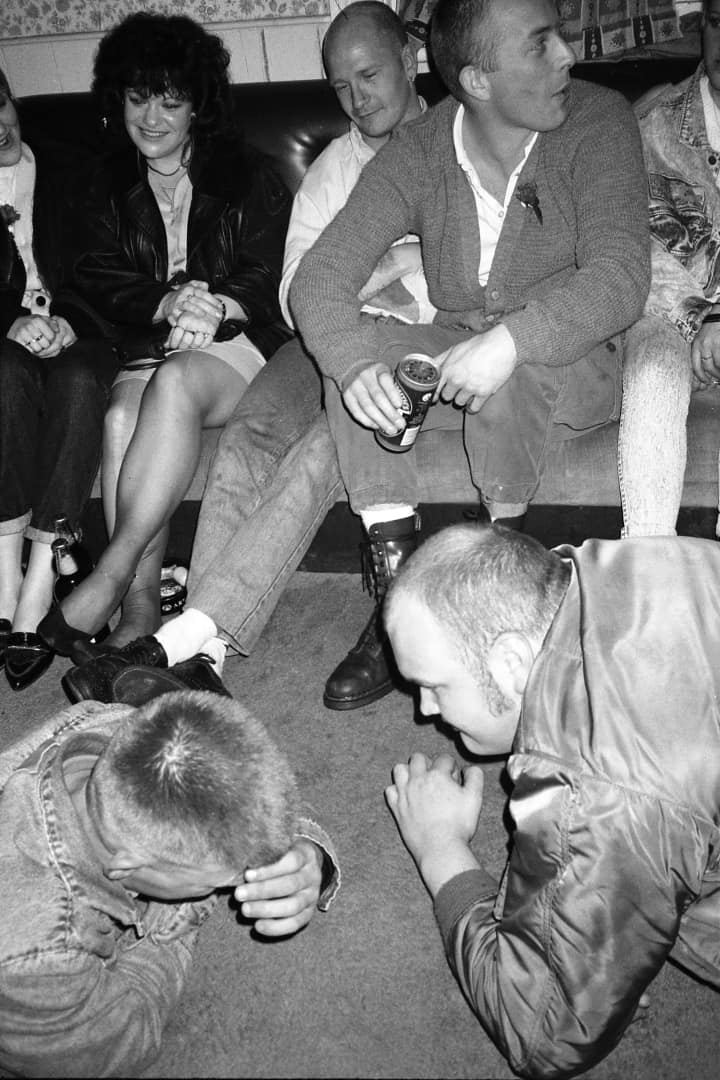

In the late '70s, growing up in a low-income housing estate on the fringes of London, when he wasn't scuffling in the streets or listening to punk-infected ska music, Gavin Watson took pictures. Mostly, Watson photographed his younger brother and friends, a crew of athletic, accidentally stylish, misunderstood teenagers. They were textbook skinheads: headstrong, music-loving youths in checkered button-ups, Dr. Martens boots and army trousers. When the skinhead aesthetic was born in the late '60s, it was in reaction to the more fashion-conscious Mods. Because the style was later adopted and altered by white supremacists in England and abroad, the skinhead look would become a very stigmatized one, a development that is almost ironic, considering that it was so heavily influenced by Jamaican rude boy and reggae culture.

Gavin Watson had no clue that his black-and-white photographs would go on to become some of the subculture's most iconic images. They were compiled into a monograph called Skins, published in 2007. This fall, when Dr. Martens decided to launch the Spirit of '69 line, a capsule collection inspired by the skinhead uniform, the brand went straight to the source, reviving the classic look with a perfectionist's accuracy and enlisting Watson to shoot the lookbook. We spoke with the photographer about his serendipitous documentation of the movement, moving past stereotypes and the long-lasting influence of skinhead style.

Were you surprised when Dr. Martens recruited you to photograph this new collection? I'm a cocky fucker. I knew I should be doing it. I've seen so much of my work ripped off. The powers that be, like the big photography institutions—I've never even had a phone call from them. They don't want to really help people that haven't been through their system. People are like, “Fucking hell. Look at him: he got kicked out of school when he was 15. What the hell am I paying 40 grand for?" I know that sounds a bit paranoid, but I think I've been on the planet too long to not realize how it works. I photographed my brother from age 10 to 20 and my friends from 14 to 23. No one ever gave a fuck about us or my photography. I hid away from it all until my dad said, “Son, it's not going anywhere. You can stay at the fucking pub drinking yourself to death, but if you don't do anything with this stuff, then somebody else will." The next thing you know, I'm doing major advertising campaigns. It's been a really interesting journey from the little skinhead I was to the photographer I am now. I'm still fucking broke, but, other than that…

"That was the beauty of being a skinhead: you could look good very cheaply."

Did you consider you and your friends to be fashionable at the time? Weirdly, no, not as much as people think we are now. I wasn't a purist. I wasn't making damn sure that my turn-ups were the right length or that I had the right shirt. Now, I've become a sort of fashion commentator, which I find bizarre. I never had any money to buy any fucking clothes. That was the beauty of being a skinhead: you could look good very cheaply. You had the core uniform, which you found out about through whatever means you had before the internet. You got a checked shirt—any checked button-down would do. But boots were different; you had to have Dr. Martens. Any uniform is open to interpretation, but not too much.

Do you think that the new collection accurately captures the skinhead spirit? Yup. I was surprised when I saw the pictures, actually. Dr. Martens is incredibly brave for doing this, and it's about fucking time to have a clothing line that actually brings a little bit of education to it. They've modernized it and put their own slant to it instead of just trying to copy something from 1969, and I'm very into that. It's all about when the skinheads were getting into music. They all loved reggae; it was a really big discovery for them. Now, they've got a new uniform to wear, really, and I don't think there's anything wrong with the marketing [aspect], either, because it's not like skinheads love making their own clothing—we were buying Levis and Ben Sherman shirts. We were buying big-company brands.

Have you noticed a lasting influence of skinhead culture? Yes. Now that the stereotypes are over with, and the demonization is over with, we can live through the music and the positive side of it. Music is everything—it's what connects it all. I have noticed it's really been embraced. Wherever you find a working-class country like Mexico, you'll find skinheads. Same with Malaysia, even China. I've got a picture of a Chinese skinhead in front of that big fucking Mao Zedong statue in Red Square.

Growing up, as you were running around with the other skinheads, did you ever feel like an outsider? I was different from the early days. I didn't speak until I was 4. I had to spend time in special schools and shit, and I spent most of the other time in my own world. I was living in this brutalized environment—on all levels, not just physical. I built a big fucking wall around myself, and then the skinheads came along, and it was perfect for me. Ultimately, you become a skinhead because of the music. The 2-tone movement was the reason that I became a skinhead. We all go through it at 14. It's universal. The adrenaline and testosterone and all that shit running through you—you don't know what the fuck is going on. When I saw Boyz in the Hood, I was like, “That's us with guns." The human dynamics are the same. When I was with my boys, young and tribal, I felt so deeply about it. I thought it'd be forever.