How We Partition Black Masculinity

Carefree black men have never been allowed to exist on their own terms. It’s time we let them.

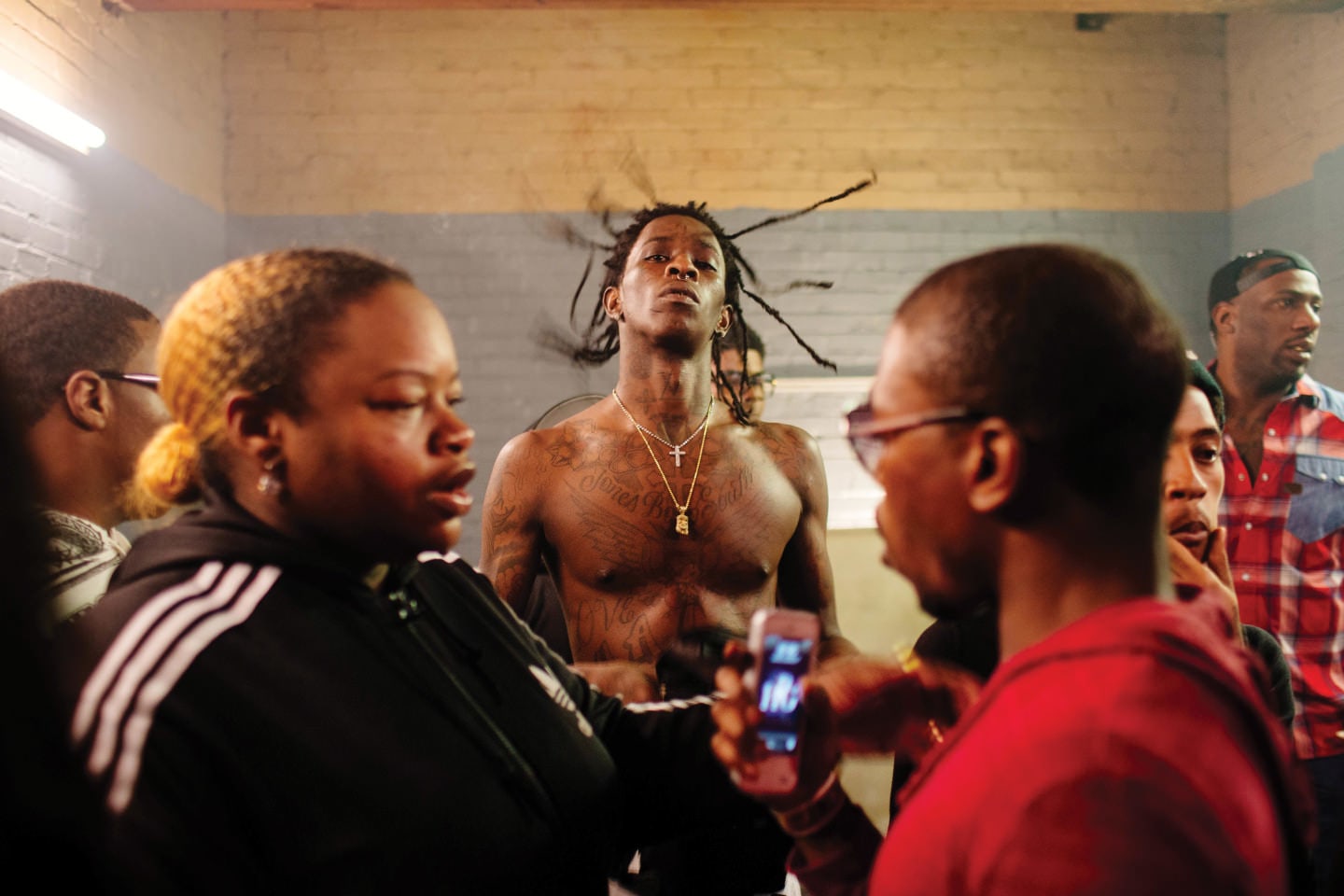

Kendrick Brinson for The FADER

Kendrick Brinson for The FADER

They’ll think I’m gay, Warren said. It was 2009, and he'd joined the high school varsity basketball team as a freshman. We were best friends and, naturally, I was happy for him. I was ready to be at every game and cheer him on, not realizing that his participation meant the end of our friendship. Warren's statement ricocheted in my head, growing louder: They’ll think I’m gay. They’ll think I’m gay. They’ll think I’m gay. This belief — one that is tethered to the projections of others and one I would again encounter — was based on a set of rules meant to discipline: men don’t put their hands on their hips; men don’t walk with a twitch; men don't act like women; men don't express vulnerability. In the moment — a mix of anger, disappointment, and confusion — all I could think was, Why?

There is a partition to the black men we build. They are veiled in notions of hypermasculinity not of our making. It’s why black boys are prepared for battle at a young age; we know the world is no safe haven for them in the years ahead — and even more of a threat to black girls and women. Yet in doing so, we limit them from a land of possibility.

For years now, I have gone about living my life as a carefree black man. Here, in this in-between space, there is a feminine delicacy assigned to my selfhood. It’s based on the way I dress and the way I talk, all southern drawl and careful enunciation. I'm a gay man. But not all carefree black men are, and what one decides to wear or how one decides to move throughout the world doesn’t have to say anything about their sexuality. Odell Beckham Jr. navigates this space. Jaden Smith does, too. As does Young Thug and Kanye West. To certain spectators, we are not always considered men, a label that has come to symbolize courage and emotional indestructibility. Instead we're viewed as oddities: flawed creatures who brim with emotion, wear atypical clothing, or, in Thug's case, call close friends “babe” and “lover.”

Consider the curiosity Odell Beckham Jr. courts on the field. In some circles, the pro-footballer is better known for his hair and animated dance moves than he is for his stats as an all-star New York Giants wide receiver. In January, a compilation video of him dancing appeared on YouTube. Clips of his playful pirouettes, loose-hipped Whips and Nae Naes circulated across Twitter and Facebook timelines, spreading like wildfire. Every movement Odell made was scrutinized. Every action questioned. Like other men who wear their masculinity freely, he was thrust into the realm of suspect.

Similarly, when Jaden Smith became the face of Louis Vuitton’s SS 2016 campaign in an exquisite skirt and mesh top, he was, again, deemed gay. This happens frequently: a man does something — anything — that diverts from the norm and is lambasted for it. In high school, depending on where you grew up, this might have been the black kid who wore his pants too tight. Or maybe there was a time you found a friend singing too loudly to Beyoncé’s “Flawless” and, even if only for a moment, doubted him. Lest we forget the time Kanye donned a Givenchy kilt and was publicly chided for it. Or when Drake spoke a bit too highly of Lil Wayne and was greeted with raised eyebrows. In March, critics condemned the affection actor Michael B. Jordan and director Ryan Coogler seemed to be showing for one another in an image from Vanity Fair.

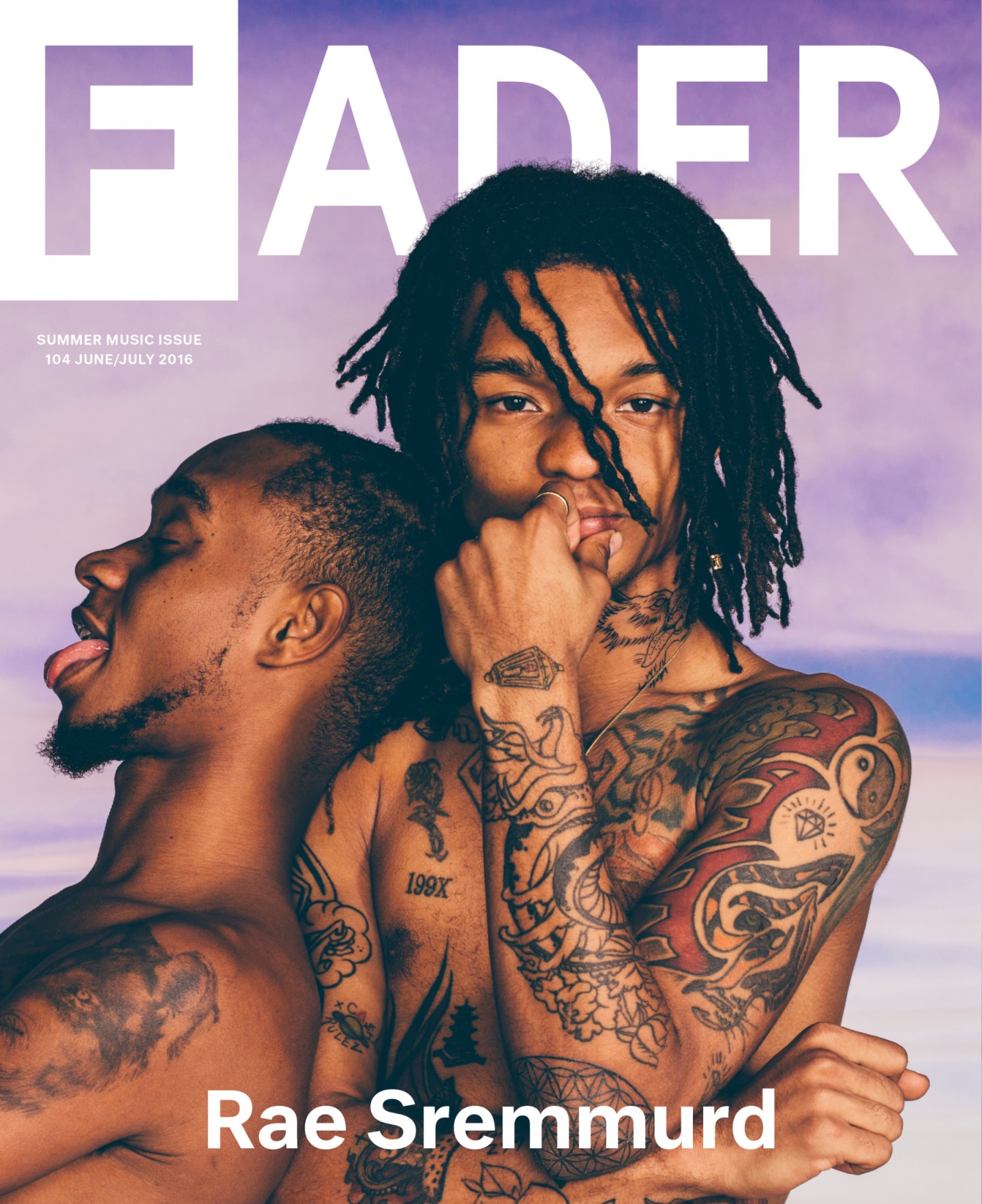

Alexandra Gavillet for The FADER

Alexandra Gavillet for The FADER

Even just last week, on the occasion of FADER’s Summer Music cover — which depicts Rae Sremmurd’s Jxmmi resting on Swae Lee’s shoulder — the brothers were attacked for looking soft. “The goals of the media is to feminize black men,” leylathickfit wrote in the comments of an Instagram post by The Shade Room, referring to the cover image. Another Instagram user, motivation_needed_, said just a few lines below: “...the photo it looks feminine and they’re not females nor are they gay so why do they need to look feminine?” Chef cheeba added: “Y’all gay asf.” When our black men appear vulnerable, well mannered, or delicate, we dismiss them into a realm of questioned sexuality. We'd rather grind them into muscles and fervor, snatching them of expression and thought. By most categorizations, a prized man is typically strong and solid, a vision of comfort and sturdiness, the care-taker, the provider, but never free. This needs to stop.

There were times when I wasn’t allowed to be free. The clearest memory I have of being caged came in 2011, two years after my friendship with Warren began to dissolve. I was 17 and had recently decided to not sign up for JROTC, the junior army program offered to students. I happily arrived home that day with a new schedule, forgoing military training — which, I was told, would be good for me — for an economics course, and decided to take a nap. Enraged with my decision and my condition, as it was then described, I was awakened from my sleep by my stepfather — he'd burned me with an iron.

There is a line in Toni Morrison’s novel Song of Solomon that reads: “If you want to fly you have to give up the shit that weighs you down.” It is time we allow our men to fly. We limit them, we shape them, and place them in boxes we often despise. No longer can we trap men like Odell, Jaden, Thug, or two brothers from Tupelo, Mississippi who just want to make utopian rap music, in useless expectations of masculinity. The men we love, the boys we love; they’re dying — at the hands of police, private citizens, and individuals like Omar Mateen who use hate as a reason to kill. Who then are we to limit them in living their lives on their terms?

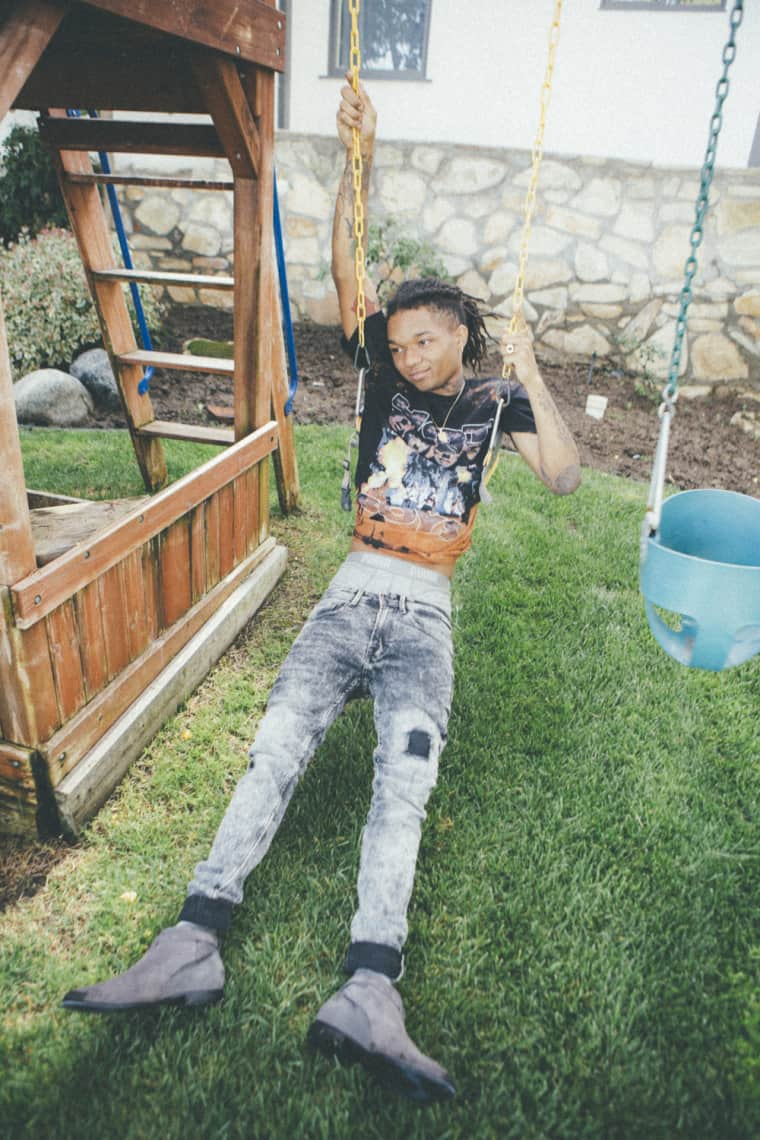

Alexandra Gavillet

Alexandra Gavillet

Alexandra Gavillet

Alexandra Gavillet

It took Odell a fight on the field and a vicious helmet snatch to quiet those who challenged his masculinity. And who knows what it may take Jaden to get the world to reckon with his individuality, but shouldn’t we support him either way? It’s time we permitted the same carefreeness we do to those who are unbound by the limits of society to our black men and boys. It isn’t gay for any man to wear a dress, nor is it gay for a man to dance or bleach his hair. A man choosing to do his own thing, to slice through a sea of sameness, is nothing more than a bold stance of defiance, a claim of independence.

I don’t want to suggest that freedom comes without consequence. Last June, the Huffington Post published a piece that critiqued the carefree black boy movement. The writer argued that freedom was allowed only to men who'd amassed wealth and fame. He believed that death, alongside ridicule, was a possibility for being a carefree black boy. And while this may be true, the political and social realities of blacks have remained largely unchanged since we first arrived in America. Racial terror may take on different forms, but it is terror all the same. As we witnessed this weekend at Pulse nightclub in Orlando, hundreds named and unnamed are murdered for simply being. At any point the system might kill us, and to suggest we should not make an attempt for freedom is equally limiting.

We’ve asked our men to fight for us a million times in a million different ways. The only mantra we should now extend is a careful and courageous one: fly for us.