Sheida Soleimani in front of new work, titled "Medium of Exchange." Image courtesy the artist.

Sheida Soleimani in front of new work, titled "Medium of Exchange." Image courtesy the artist.

Artist Sheida Soleimani specializes in telling stories that are not her own. They are the stories she was told as a first-generation American in Cincinnati, Ohio — many of them about her Iranian parents in the early 1980s living under the Shah and Ayatollah regimes; her father evaded the government for three years while her mother was imprisoned and tortured.

“I joke that I grew up as a Middle Eastern in the midwest,” says 26-year-old Soleimani, who didn’t know any other Iranians outside of her immediate family. Her parents encouraged her explorations in political art, which were influenced by her father’s activism and her mother’s painting and sculpture. Soleimani’s mother encouraged her early work, and, perhaps unknowingly, inspired its subject matter. First depicting the violence her mother endured, Soleimani eventually expanded her scope, drawing from the stories and photos of Iranian women who had been killed under Sharia law — culled from stories she found online in forums, on Human Rights Watch, and across the dark web. In many cases, these women just disappeared without a word.

Soleimani isn’t content to let their stories end this way. Her first series, 2014’s “National Anthem,” featured a range of images of women and men affected by human rights violations. In later works, her photographic dioramas fused symbols of trade with objects of femininity, bringing her praise and attention in America and threats from the Iranian government.

“I started getting a lot friend requests on Facebook and accepting all of them,” says Soleimani, originally excited by the prospect of connecting with Iranians who appreciated her work. “Fifty percent of those people ended up being members of Basij, the neighborhood militia, who started harassing me about the work I was making.” The threats got more serious: “If you ever come to the country,” they said, “We will cut you apart limb by limb.”

But Soleimani accepts that her art puts her at risk. Currently a part-time professor at the Rhode Island School of Design, she knows she won’t ever be able to visit Iran. Though she does remain hopeful. “I know that creating awareness will eventually help in the long-term,” she says.

Here, Sheida Soleimani tells her story in her own words.

SHEIDA SOLEIMANI: I grew up in Cincinnati. I didn't learn how to speak English until I was about six or seven years old. We only spoke Farsi in the house. I only heard Persian stories. Except for religion, I was raised as a pretty traditional Iranian child. My connection to Iranian culture has always been through my parents and the stories they told me growing up. I learned about my so-called “home country” by hearing brutal bedtime stories and experiences from my parents — like my dad hiding for three years in the mountains, both of my parents being imprisoned, or what it was like to work at a leper asylum where people's limbs were falling off. It was probably too intense for a child to hear, but I learned the truth at a very young age, which I’m thankful for.

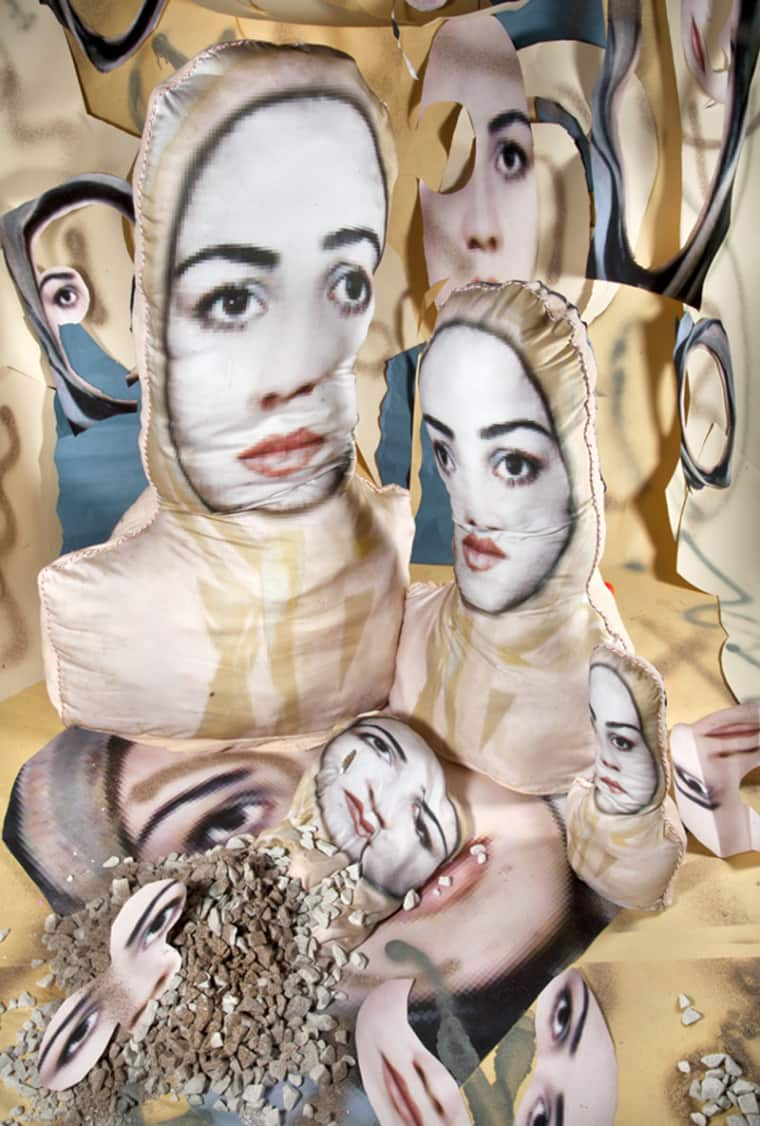

"Maryam," archival pigment print, 2016

"Maryam," archival pigment print, 2016

"Taraneh," archival pigment print, 2016

"Taraneh," archival pigment print, 2016

My parents came to America at separate times. They both escaped and reunited in New Haven, Connecticut. My dad was granted political asylum, and then he got accepted into the medical residency program at Yale. Then he got a job as a doctor and researcher in Indianapolis, and then after he went Cincinnati. I never knew any other Iranians growing up there.

My mom always drew, painted, and sculpted. She was always more of a creative thinker than my father, who was more of a political thinker. I just combined those. Growing up, we would go to super midwestern chain restaurants with paper table cloths. They would give me crayons, which my mom would take and start drawing naked people. I would be super embarrassed. Western philosophy teaches us that nudity is not OK. To her, it was totally normal.

When I got to art school, there were a lot straight, white men who were very apathetic and generally exoticized my output. They gave me problematic yet beneficial advice. They would say, “You have all of these important stories about your family, but why do I need to care about what happens to you?” At that point, I was making highly personal work. I was 21 and made black and white images that put me in the place of my mother when she was in prison. Then a professor challenged me and made me realize that I wasn't doing it right. At that time, “Internet art” had just taken off. I thought that I could use all of these source images from Google Maps and Street View and make work. It ended up meaning nothing.

"Administrator," archival pigment print, 2015

"Administrator," archival pigment print, 2015

The fact of the matter is that people in Iran are unable to talk about this. They don’t have the means to, because they live under a religiously motivated totalitarian regime.

When I got to grad school, I realized I could take this language that means something specific to me, and make it more communicable to a global audience. This meant thinking about stories that happened not just to my mother, but to women across Iranian society, and trying to show them to a global audience.

I knew from the graphic stories my parents told me that horrible things happened to other women, people who were homosexual, or people who defied religion. Increasingly, I became more curious about the cases happening as a result of Sharia law, which result in women being killed. I would find Amnesty International articles and forums that family members were posting in. They’d be like, “My daughter went missing on this date, can anyone verify if she has been found?” I started taking screengrabs. Often these women were being taken in by the government without their families being alerted. Sometimes they'd be put on death row or on trial. Sometimes they wouldn’t even get a trial.

Through searching for these things, I started slowly unearthing stories about more and more women. The only information left about them were these web-sized images, which are around 72 pixels per inch and really blurry. I was like, ‘OK, if there are no traces left of these people, except these tiny, pixelated photos, I'll just use it to start creating a conversation about people who have disappeared.’

The trials and cases of these women are all based on Sharia court, which is under Sharia law. There's Haram and Halāl. Haram is bad by law, and Halāl is OK by law. There are specific rules that are OK and not OK. One of which is for a woman to attack a man. If a woman attacks a man who tries to rape her, regardless of whether she gets a trial in Sharia court, she did something that was not acceptable. The law is literally an eye for an eye. If you do something that is Haram, you go to jail or get executed depending on the offense.

Eighty percent of these executions are based on false drug trafficking charges. They’ll say a woman was found selling cocaine or smoking marijuana — things that, in the U.S., you'd get an offense or go to prison. In Sharia court, there is an execution. The other 20 percent are things that happen to women, like attacking a man, or a false murder accusation for something a man did and blamed on a woman.

"Sholeh (maman)," archival pigment print, 2016

"Sholeh (maman)," archival pigment print, 2016

Source image for "Sholeh (maman)," 2016

Source image for "Sholeh (maman)," 2016

Despite all of this, there are misunderstandings in the west about Middle Eastern women. The west thinks that Middle Eastern women are repressed, which is true in many cases. However, whether that be by choice or by force is a different question. Many Middle Eastern women choose to wear hijab, because it’s a religious choice. I was raised without religion completely, and I don't adhere to any religious philosophies, but I think that people should have the freedom to choose.

In the west, people don't really understand that some women want to choose to cover themselves. In my work specifically, I talk about Iranian women who don’t have a choice to decide. After the revolution when Ayatollah Khomeini came into power in 1979, he promised freedom for women yet immediately made it mandatory for women to cover themselves. He basically took away any rights for women, including reproductive rights.

Last week the New York Times published a really long essay about the history of the Middle East. It talks about how these countries have had problems because of their relationship with the west, and how the west colonized these areas. It’s about how, as Americans, we should understand that the situations in the Middle East are, in many ways, because of western involvement. There needs to be a fine-tuned understanding of what the differences between Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Afghanistan, and Iraq are; they often get lumped together, which is very problematic.

In my recent work, I’ve started thinking a lot about symbols that are specific to Iranian culture. Ninety-eight percent of the economy is the oil trade, and the other 2 percent of the trade is agricultural — like pistachios, grapes, and rice — which I put in my work using images sources online. I also put sugar cubes, which reference suppression and sacrifice. My mom told me about how animals are sacrificed in Iran. Sugar cubes get put in their mouths to pacify them before their heads get cut off.

"Filleting," archival pigment print, 2015

"Filleting," archival pigment print, 2015

I’m also thinking a lot about social media: how it's become such a big tool in uprisings, and how we utilize it to disseminate images that would not be seen if we didn’t have tools like Twitter and Instagram. A lot of the images I’m using are directly sourced from social media and people in revolution in Iran. People share photos of what they look like after being burned with acid, or beaten by the government for being homosexual. All of these image-sharing sources are a way to create a post-human collage. Humans collage everything we see and trend towards what we like based on what we look at on our phones. Who we even subscribe to on social media is a method of visual collaging.

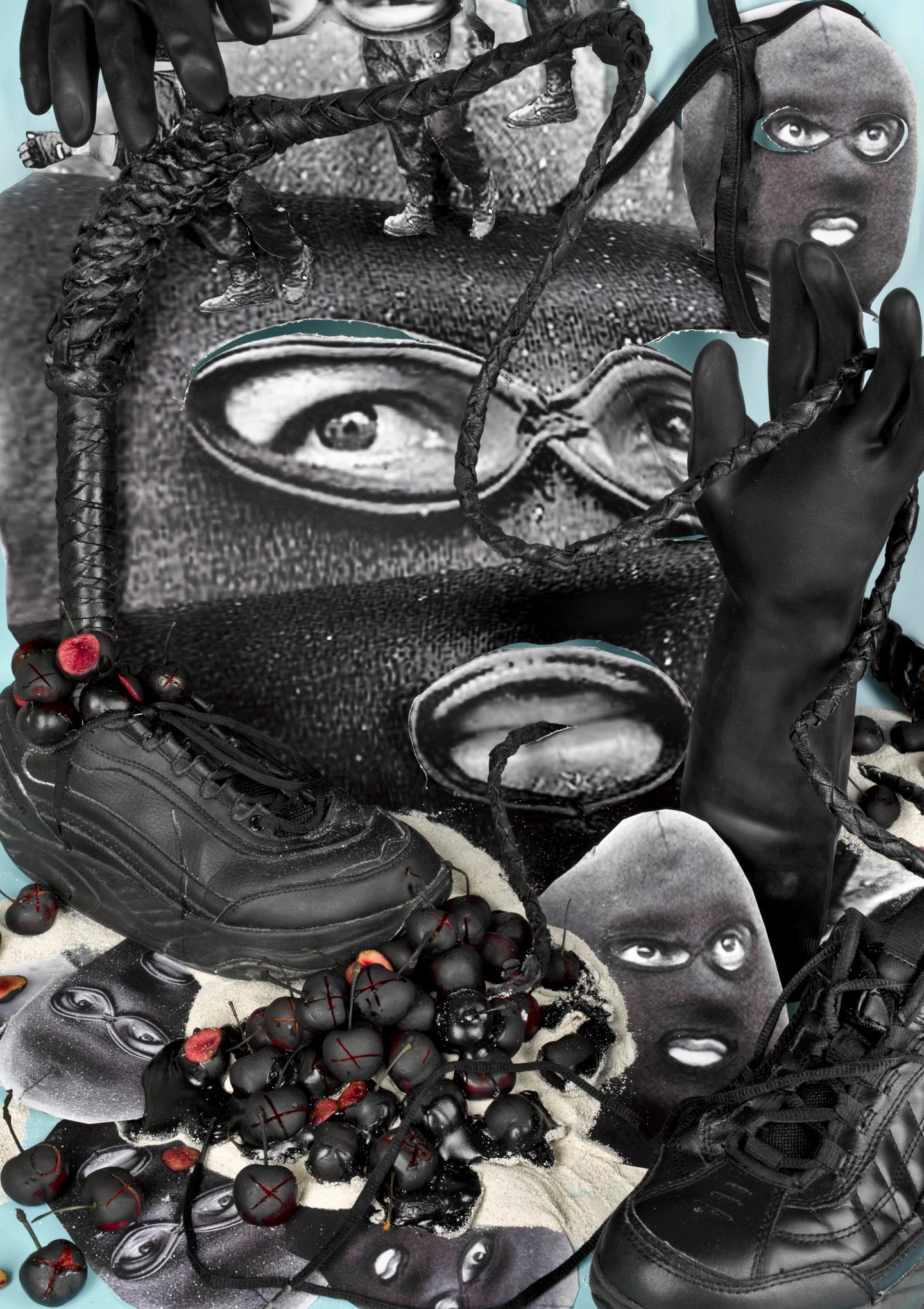

I also recently started a new body of work: writing screenplays for specific characters who are male political leaders. I’m talking about how all of these political economies are dominated by men, and how men often control the bodies of women. I’m having female actresses be the roles of the politicians. I’m talking about what is a medium of exchange, money, or monetary systems between western and eastern countries, or the basis on which they operate. Sex, war, and politics, in short. I’m thinking about not just Middle Eastern politics, but how these politics dictate the west’s relationship with the middle east. Oil is the main answer. Recently Saudi Arabia strong-armed the United Kingdom into continuing to buy oil from them, even though the U.K. wanted to call them out on human rights violations.

I know if I went back to Iran, my life would be threatened. It’s a choice that I’ve made. I’m not unhappy about it. The fact of the matter is that people in Iran are unable to talk about this. They don’t have the means to, because they live under a religiously motivated totalitarian regime. I have the luxury of living under a regime that isn’t like that. I can say what needs to be said for people who are unable to say it.

Sheida Soleimani has two upcoming solo exhibitions: Civil Liberties at BOYFRIENDS gallery, opening September 23 in Chicago, and Medium of Exchange at 1305 Main for FotoFocus, opening September 30 in Cincinnati.