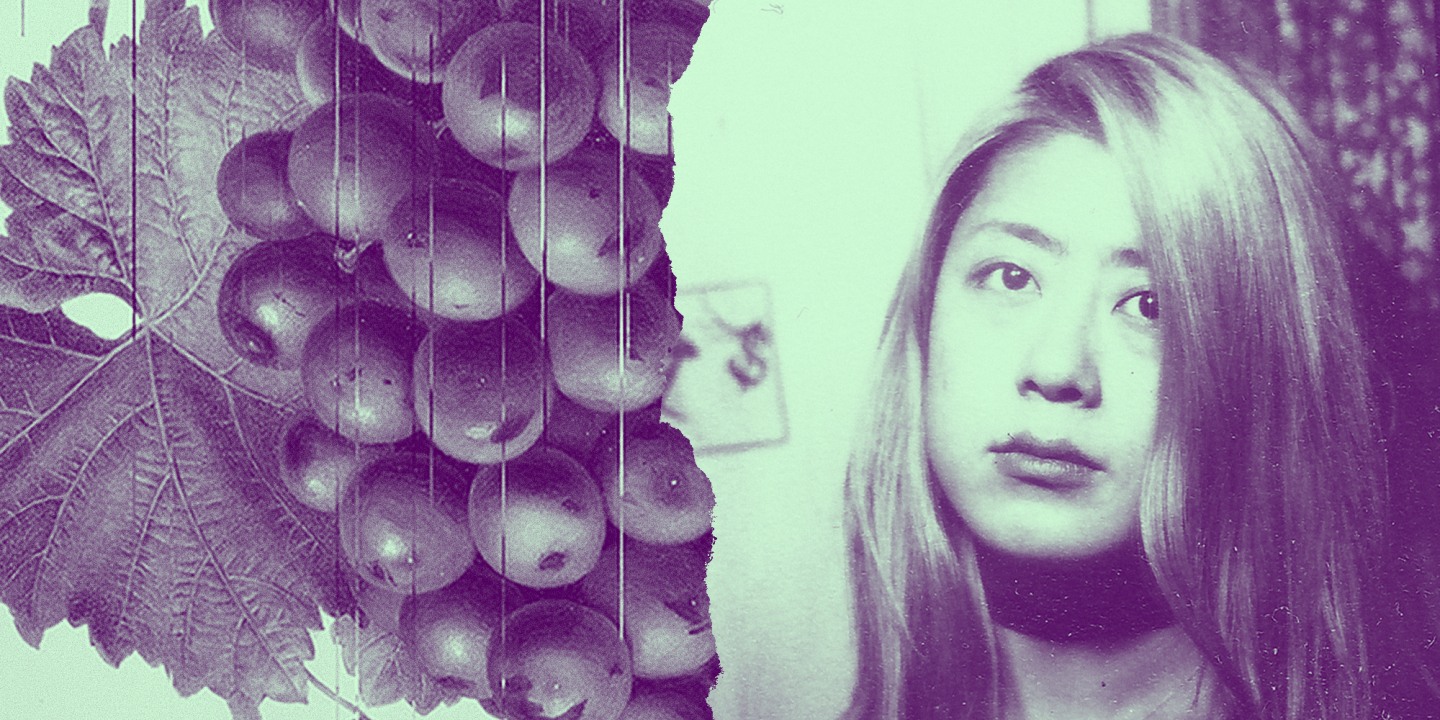

Jenny Zhang’s Coming-Of-Age Stories Will Leave A Mark On Your Heart

A conversation with the writer about being shy, gross body stuff, and her gorgeous first story collection, Sour Heart.

It’s yucky to grow up, especially in a roach- and rat-infested city like New York. Sour Heart, Jenny Zhang’s stunning new collection of short stories, stares adolescent body functions right in the face. On the very first page, there is some generous talk of bowel movements, because how can you describe being human without talking about shit? There’s real passion behind it, a reason for the graphic image; Zhang never shies away from the reality of women bodies. We poop, too.

Zhang completed Sour Heart's stories over the course of 13 years, in between studying in Iowa and freelancing as an essayist for Rookie. Zhang, 33, moved to New York from Shanghai when she was five, spent her first seven years in Queens, and then moved out to Long Island with her family. “I’m a New York kid,” she told me, over the phone from her Brooklyn home last week.

Zhang's stories are fiery, tender, mercilessly candid. Every chapter follows the story of a different young girl, each grappling with a perfect storm of hormones, communication issues, and loneliness. It’s essentially a deconstructed bildungsroman, hinged on the exhausting mindfuck of trying to figure out who you are.

“Being someone is terrifying,” she writes in “The Evolution Of My Brother,” a semi-autobiographical story. Home from college, the story’s protagonist Jenny muses about finding compromise between family and independence: “I long to come home, but now, I will always come home to my family as a visitor, and that... reverts me back into the teenager I was, but instead of insisting that I want everyone to leave me alone, what I want now is for someone to beg me to stay.” Jenny (the narrator) grapples with the heartache of learning that the autonomy she always yearned for is, in practice, really fucking hard.

After Zhang and I spoke about warped memory, skin and stomach problems, and our younger brothers — a conversation that you can read below in full — I asked her if it’s true what I’d heard, that she’s working on a novel. “If someone told you it was coming out, they were being very generous to my ability to complete work,” she answered, with self-deprecating charm. “I’m working on one, but I seem to have problems writing what I’m supposed to be writing, which is like, important, grand-sweeping novels. I’m drawn to littler things. But I’m trying.” Sounds pretty damn promising to me.

Sour Heart reminds me of Junot Diaz’s short story collection, Drown (1996). Not only are these New York immigrant coming-of-age stories, but each one is connected by characters who keep appearing in others’ stories.

JENNY ZHANG: I’m so glad you said that. I hadn’t thought about that book in a while.

After writing a few of these stories, I started to feel like these characters probably knew each other, and existed in the peripheries of each others’ worlds. Some characters go to school together, and some of them all lived together in one room, in the early years of hardship in America. When immigrants move to another city in another country and have to build these provisional communities and families, they often end up being the communities and families they roll around in for the rest of their lives. It’s a very common facet of immigrant life, and I suspect that’s why the stories in Drown have that similar feature.

There’s my family, then there’s our immediate family friends, but then there’s almost like an entire universe ... it’s like the Immigrant Universe instead of the Marvel Universe. Some [characters] become very central to some kind of lesson, or some kind of notorious story that gets told a lot after a couple of drinks. And some are more rare. That was the feeling I was trying to evoke in these stories.

One of my favorites is “The Evolution Of My Brother,” probably partially because I have a little brother. I was struck by the scene where Jenny reminisces about the interactions — both good and bad — that she and her sibling have had. What has your older sister experience been like?

There’s a lot of responsibility as an older sibling, and being a big sister in particular is a very gendered responsibility. There’s a bit of an expectation — especially if you’re a much older sister — that you’re gonna play mother; it’s like your first practice run at being a caretaker. And honestly not everyone is suited for that. Certainly not when you’re like, a young girl. As you get older, you’re like, There were things that happened to us as kids and they will shape us forever. But also there are just as many things where you’re like, I wasn’t affected by that, or That wasn’t a big deal, and someone else has been regretful about that since it happened. You know, where you feel, I owe it to this person to really apologize for all that I did, and they’re like Yeah I don’t really think about you. We both overestimate and underestimate how important we are to other members of our family. You’re kind of constantly wrestling with signifying too much, or signifying too little.

It’s also less clear with siblings. The parental-child relationship has been pretty clearly outlined by society: the parent is supposed to take care of the child they brought forth in the world, and the child is supposed to show some kind of love and gratitude for their parents. But with siblings, it’s not like there’s a mandate that you’re supposed to be friends with everyone you’re blood-related to. A lot of people are really close friends with their siblings, but a lot of people say, “If I wasn’t related to this person, I don’t think I’d like them!" It can get unclear, especially as you get older and you have your own lives.

“There’s a lot of gushing in these stories. These girls are talking voluminously; they’re rambling and they’re ranting and they’re just like splooging all over with their words.”

Another detail I loved in “We Love You Crispina” and “You Fell Into The River And I Saved You!” was the itching that the main character is plagued by. And, because hers are the opening and closing stories, that means the book is bookended by itching and scratching. What was your motivation for that?

These stories don’t really shy away from the body, what the body can do, and what the body is troubled by. There’s a lot of gushing in these stories. These girls are talking voluminously; they’re rambling and they’re ranting and they’re just like splooging all over with their words. They’re splattering.

The main character suffers from really dry skin; it’s not producing enough moisture. She’s missing that protective seal. I think in writing I realized that, much like in my own life, when something goes wrong emotionally, or there’s a psychological disturbance, it shows up immediately on the body. Studies have shown [that’s especially true] for people of color. Asian-Americans are more likely to say, “I’ve had this headache for a year,” than to be like, “I think I’m depressed.” When you’re a child, especially, you don’t necessarily have the language to speak about your emotions. But it all shows up as distress on the body. In the first and last story, even though there is relief, the narrator is going through constant changes. I didn’t consciously try to be like, Let me let this eczema symbolize… but looking back, I realize that that was an unconscious decision I was making.

All the gross body stuff is great. In “You Fell Into The River And I Saved You!,” Christina is overwhelmed and constipated, which also reminds me of “The Empty The Empty The Empty,” where Lucy has a dream that she’s screaming and no one listens to her. Both moments have to do with trying to get something out and not being able to. Do you feel like that? Is publishing this collection a release for you?

We don’t get a lot of chances in life to speak without being interrupted. Or to speak without someone saying what they think, or passing down judgment. It’s very hard to speak and speak and speak about what you need to say. I would like everyone in the world to have a safe zone to speak into, but there just isn’t one.

I was very shy growing up. I think shyness can be innate, but shyness can also be enforced by your environment. The first five years of my life living in Shanghai, I was the opposite of shy: I was insufferable, talking all the time. People were like Can you stop talking? I need to rest. I couldn’t! I loved talking. I found such joy, and I thought I was entertaining other people. But when I came to the United States, because I couldn’t speak English very well, the first few months I was there, the thought got reinforced that I don’t have good things to say. I’m not interesting, I’m very bothersome, or I’m not understandable to others. I became very shy. But I still wanted to speak. I think everyone wants to be seen in some small way. So writing gave me a lot of relief, to have a place without the scramble of judgment, where I could think and make mistakes and correct myself.

“We don’t get a lot of chances in life to speak without being interrupted. Or to speak without someone saying what they think, or passing down judgment. It’s very hard to speak and speak and speak about what you need to say.”

Sour Heart’s characters are each searching for a sense of self. Can you relate? Do you feel like you’ve figured out who you are yet?

I have not. But the voices crowding my brain are a little dimmer. And by voices I mean other people’s voices. When you’re young, if you’re lucky, you get to develop your personality for a while in a supportive, loving environment. Not everyone is lucky. But there always comes a point where you have to interact with unknowns, like going to school. The instant someone is like, “Hey I don’t like you,” or “Hey, you’re really ugly,” you can’t unhear that. And then you have to try to fight against that, and it takes a lot of energy. It’s very easy to give in to how people see you. I remember something as innocuous as someone once saying to me, “But you’re never sad!” when I mentioned I was depressed. And I was like, Is that how I seem? Like some happy clown of a person? Am I really so lacking in depth? It was very hard to be able to contain both the way I felt, which was like someone prone to sadness, and the way I seemed to my friend who thought of me, in a very flattering way, as being very capable, or whatever.

I’m still very prone to what other people think about me, and I’m making myself very vulnerable again by putting this collection out there. This really does invite other people to tell me what they think they’re seeing about me. But as I get older, my core is a little more stable. And I’m constantly trying to stabilize my core — not in the physical sense, ‘cause I still physically topple over…

I know what you mean! Your emotional core. Does finally releasing Sour Heart into the world help stabilize that core?

I think it definitely helps in the sense of like, I’m done exploring these obsessions. I must have found something endlessly mysterious or interesting about these characters and these stories and these themes. But now I’m done. I am no longer in control. The life of this book is no longer in my hands. It’s freeing, in a sense — it now belongs no longer wholly to me, it means I can move on. It’s a funeral for me, and for my relationship with these stories. But it’s hopefully the beginning of someone else’s relationship with them.