I inherited my relationship with food from my mother. Now I’m learning to shape myself.

New York photographer Gioncarlo Valentine on his childhood, mental health, and eating to sleep.

Self-Portrait, 2016

Self-Portrait, 2016

“My body is a cage. My body is a cage of my own making. I am still trying to find my way out of it. I have been trying to figure a way out of it for more than twenty years.” —Roxane Gay

I recently finished Roxane Gay’s book, Hunger. In it, the feminist icon carries us on a visceral journey through her battles with her unruly body, her struggles with self-love, and her recovery after a sexual assault. In reading Hunger, I felt many connections to her story. There was the shame of allowing oneself to grow so big and so fat; the use of food to fill in a void; and the bottling up of tragedy and trauma until it erodes your innocence. Gay’s writing encouraged me to meditate on my own struggles with obesity, mental health, my relationship with food, and the nexus between them: my mother.

My relationship to food has always been eating to sleep. That is the ritual in my family, passed down from my grandmother, a fat woman, to my mother, a fat woman, to me.

Growing up, food was an object of scarcity. Although there were many times where my mother would cook meals large enough to feed the neighborhood, there were just as many times, usually at the tail-end of the month, when my mother’s food stamps were no more, where we had to scrounge for our dinner.

During these times every bite we took was borrowed. This was when I first learned the value of community. In poor, Black neighborhoods it is not unusual for families to borrow the ingredients for dinner. It was common for my mother to send me to the neighbors’ to bring back half a pack of frozen burgers, lunch meat, bread, and sugar. In return, there were times where my mother’s food stamp card circulated several houses on the block, because we looked out for each other. However, our family moved far too often to sustain many of these connections, which meant we were often left hungry.

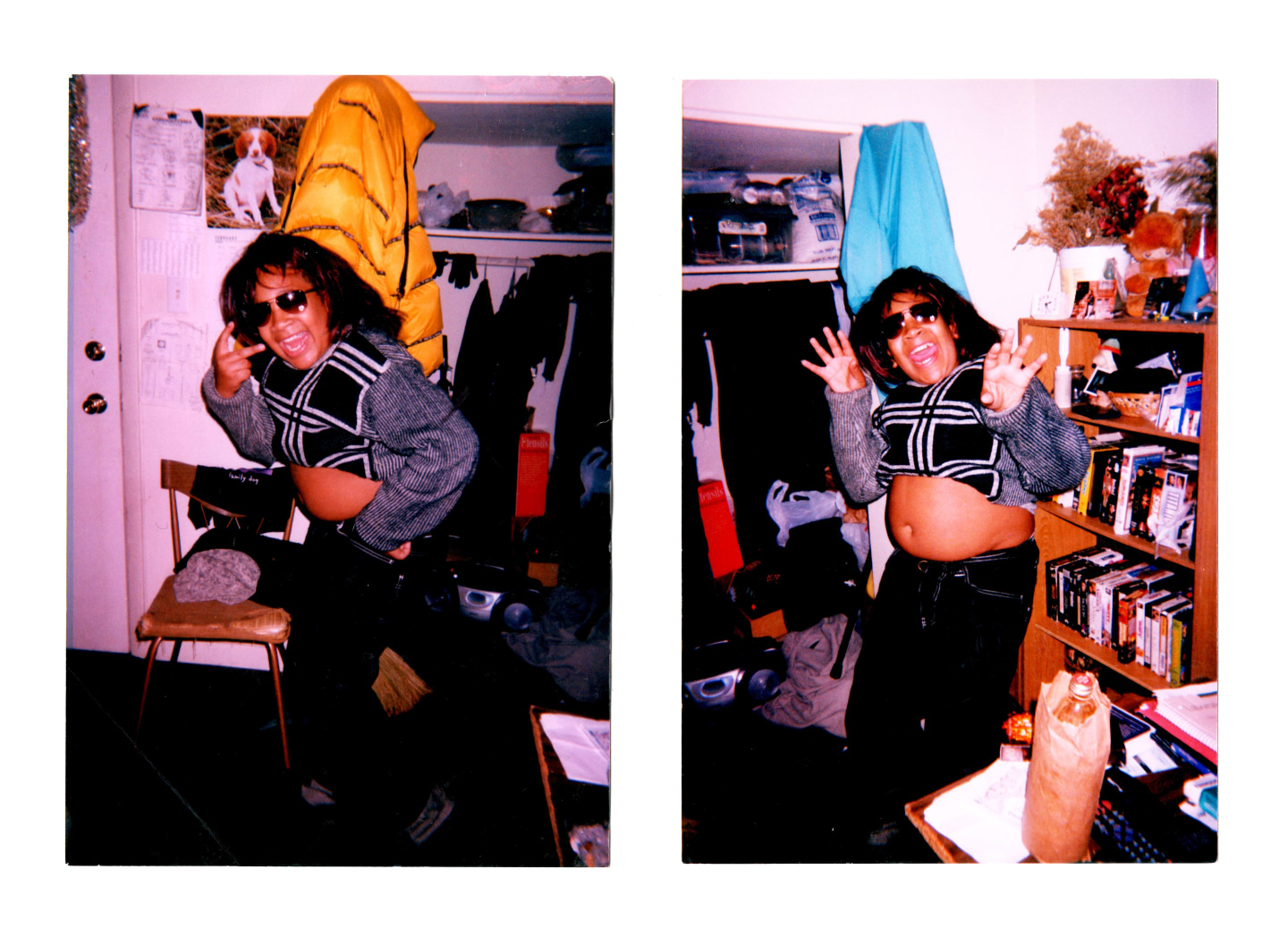

Me at 10 years old

Me at 10 years old

At the beginning of the month, when my mother would get her food stamps, we’d have snacks in the house. She would buy us boxes of Little Debbie snack cakes, bags and bags of Fruit Snacks, Pop-Tarts, nachos, chips, and cinnamon buns. But because we ate so inconsistently, we would gorge on these snacks and before we knew it, they were gone. When there was enough food around, my mother prepared meals meant to last for three to four days. She would cook enormous pots of spaghetti, hot dogs and beans, turkey necks and rice, or 15-bean soup. She would always cook late at night making her way into the kitchen at about 9.30 p.m. to start dinner. Most nights, my older brother and I would end up eating around 10.30 p.m.

Because food was limited, more often than not, we got accustomed to eating as little per day as possible. We never ate breakfast, our first meal was always school lunch: some flat and dry chicken patties or a questionable meatloaf, some listless veggies like broccoli or canned carrots, a fruit cup and a strawberry milk. Then we’d eat a late dinner at home. Although my mother put a lot of effort into making us meals, she put less effort into making them balanced. There were rarely healthy options that didn’t hail from a can because we lived in the middle of a food desert. My mother never ate when she cooked, so we never ate as a family. When she called us to dinner, my brother and I would pile our plates high, fill our cups with overly sweetened Kool-Aid, and disperse quickly to our rooms where I would watch Buffy The Vampire Slayer reruns and my big brother would listen to Three Six Mafia. My mother would stay behind.

As vivid as a picture, I can remember her sitting in the kitchen in front of the radio, sipping her Steel Reserve after she’d washed all the dishes, singing along with Whitney Houston or Anita Baker, not bothering nobody. She did this until around three or four in the morning. Then she would take a bowl of food to her room, eat half, and fall asleep. This was our formula to survive. This was our foundation.

Much like Gay’s mother, my mother showed her love with food. Whether we were living in a shelter, sleeping on someone’s couch, or in our own home, my mother celebrated my and my brother’s birthdays by cooking a feast, from which the birthday boy could take the lion’s share. It was difficult for me as a child, learning to never expect toys or games as presents.

Self-Portrait, 2016

Self-Portrait, 2016

As an adult I find myself regurgitating my mother’s ways while fighting to escape them.

On my ninth birthday, we were living in a shelter, a few weeks after my mother had finally decided to leave my abusive father. After school, some kids followed me and my brother back to the shelter and started taunting us for being homeless. I was really upset and ran inside to my mother, who was on kitchen duty. When we entered, she reached into a black plastic bag and pulled out a pack of Creme Krimpets and smiled. She stuck three red candles into three Krimpets, lit them, and she and my brother sang me “Happy Birthday.” I cried as they sang.

This moment solidified something for me, something life-changing. I understood that this would be our life from then on. This was what I had in store: poverty, transience, but more importantly, deep love. Love that was rooted not in having material things, but in valuing what we had in each other.

My mother was as devoted, loving, compassionate, and kind as she was overwhelmed and drowning in the weight of it all. She struggled because she had no one. She made sure we ate every night and had a roof over our heads as often as possible, because that was the best that she could do. Although she battled with substance abuse, she was the very quintessence of Black motherhood. I am all of the powerful and positive things that I am because of her love, but I am also all of the terrible things because of her own battles with trauma.

My mother, cooking in my aunt’s kitchen, 2013

My mother, cooking in my aunt’s kitchen, 2013

As an adult I find myself regurgitating my mother’s ways while fighting to escape them. I’ve never had alcohol, smoked, or done any drugs because of the effects substance abuse had on her. These things I was able to avoid, but the eating I was not. I often cook dinner late, sometimes even after 11 p.m. Because of this inherited habit, I get very little sleep. My body has become comfortable with an average of four to five hours each night. As was customary in my mother’s house, I eat once or twice per day on average, and I rarely eat breakfast. I cook large and hearty meals, not only because I’m still fighting my own way out of poverty and need my meals to last, but because I eat to be full, so I cook specific kinds of food. Fatty foods and heavy foods are ideal as they make it easy for me to fall asleep.

Because of the many traumas that I faced growing up, I suffer from depression. It can be tenuous, and it can be debilitating. I always believed that people eat less when they’re depressed. I'd always hoped for this side effect, but it never came. When I’m depressed, which is far too often, I binge eat. My portion sizes double. I eat and eat and eat some more until all I can feel is tired. I eat this way because sometimes the depression gets so difficult to bear that, instead of self-harming, I want to go to sleep. I eat to stay alive. In these moments food is more than mere sedative, it makes me feel warm and whole.

Socially, because I’m fat, I’ve always felt I have to play the comedian. My humor has had to be trenchant, and my personality boisterous in order to make people like me. Many of the people in my life would describe me as hilarious before anything else. Before beautiful, before bountiful, before brave. Making people laugh is indeed a tremendous gift, but it often feels like the only area that I can fit into. It’s been extremely difficult bearing the weight of depression while also performing my role as the funny, fat friend.

Finding a partner in this body has been difficult as well. Being fat is often very lonely, especially for gay men. At 27, I haven’t had a serious boyfriend since high school, but that doesn’t mean I haven’t known a man's touch. This body has been good for keeping secrets. Many men have been immensely attracted to the softness and roundness of my body, but never publicly. As a femme, gay man, many down-low men have been able to imagine me a woman, because of the doughy warmth of my frame. This has not brought me anything more than temporary pleasure. But surviving on these scraps of affection has saved my life a few times.

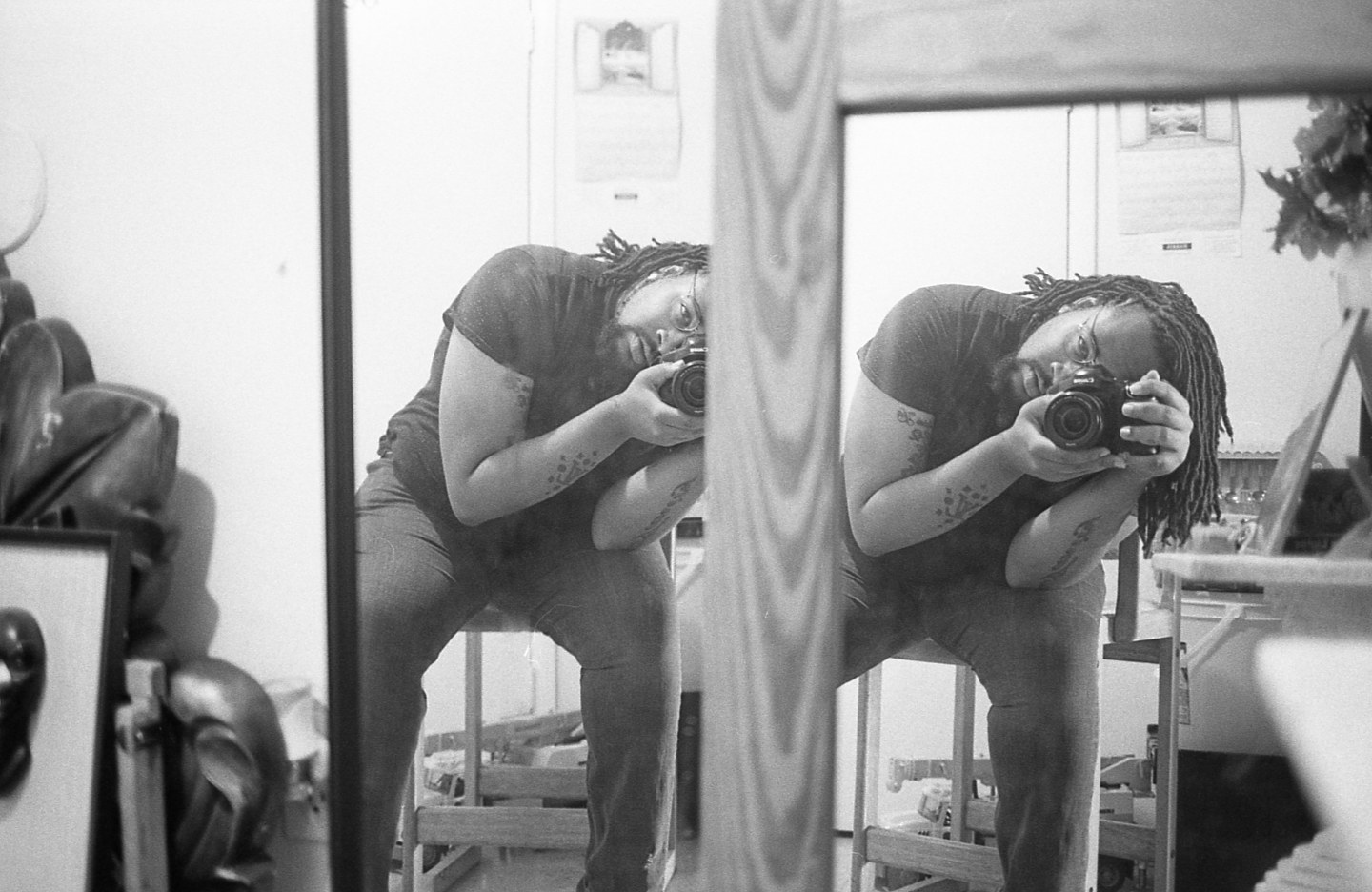

Self-Portrait, 2016

Self-Portrait, 2016

This body is the work that I’ve done, and it will take time and patience to love it into shape.

By the standards of many of my friends, I’m not “that” fat. I regularly have to reify what I mean when reminding people that I’m obese, after being asked to walk far distances, or bear with the sweltering heat. It’s like they believe that all of this weight is for show. In her book, Roxane Gay attests, “There are things I want to do with my body, but cannot. If I am with friends, I cannot keep up, so I am constantly thinking of excuses to explain why I am walking slower than they are, as if they don’t already know.” This level of insensitivity is usually subconscious. Many of my friends, as kind and loving as they are, can’t tell when their judgment is showing.

People telling me that I’m not that fat are trying to make me feel better about myself, in their minds. In actuality, they are silencing me, my health issues, and my issues with this body. They are attempting to proselytize me into their way of viewing obesity, and in doing so they’re implying that obesity is inherently bad, but somehow I am the exception, because they love me. This doesn’t help me. I don’t feel lost in my body, I am battling to obtain control of it, a control that was never modeled for me.

Until recently I didn’t even feel that ashamed of my body. My thought process was: I look good in some shirts. I wear a lot of black, which makes me look slim. In the fall and winter I can hide my protruding breasts beneath the layers with ease. I was fine thinking and feeling this way until I went to a doctor in February of 2016 and he had me step on a scale. Somehow I’d avoided weighing myself for years. I never knew that my body had gotten so, as Gay puts it, “unruly.” When the doctor told me that I was 302 pounds at 5’9, I nearly burst into tears. I started to feel every ounce of the weight I had gained. In this moment I became truly fat, because I was finally aware of just how big I’d gotten.

I went on a diet immediately and within a month I’d lost 12 pounds. Then I was fired from a job and my depression took over. During this period my weight shot up to 319 pounds. I would spend most of my mornings looking for work, my afternoons fighting off suicidal thoughts, and late into my evenings I was eating in order to get some sleep. This has been my tradition, my family heirloom. This body, recalcitrant toward its mind.

As it stands today, I weight 284 pounds. I am newly vegetarian, and for eight months before that, I was pescatarian. Every month I make adjustments to my diet, but it’s still a struggle. I still eat to sleep most nights; my depression still wields a seismic effect on my portion sizes. Very soon I plan to enroll in a gym, and I have a goal weight of 200 pounds. I’m in therapy, which is helping me to understand that these are the outcomes, this is what happens to broken people. But I’m making progress.

Reading Roxane Gay’s book didn’t challenge my views of myself or how I got to this point. I didn’t walk away from it with some new revelation or life-changing optimism. She made it clear that her writing was not from a place of triumph, but instead, from the middle of her journey. However, this book fed me, it nourished me, and reminded me that I am not alone in this struggle. It reminded me that I am not a lost cause, that I am not too big to be loved, or too damaged. And reminders can save lives. This body is the work that I’ve done, and it will take time and patience to love it into shape.

Self-Portrait, 2017

Self-Portrait, 2017