In 2015, a reporter for the New York Times Magazine deigned to ask Nicki Minaj whether she “thrived on drama.” The question, prompted by public tiffs between her then-boyfriend Meek Mill and her Young Money associates Drake, Lil Wayne, and Baby, didn’t go over very well. She went off: “What do the four men you just named have to do with me thriving off drama? Why would you even say that? That’s so peculiar. Four grown-ass men are having issues between themselves, and you’re asking me do I thrive off drama?” Nicki continued: “To put down a woman for something that men do, as if they’re children and I’m responsible, has nothing to do with you asking stupid questions, because you know that’s not just a stupid question. That’s a premeditated thing you just did.’’ And then she ended the interview.

A few years earlier, she had emerged as something of a feminist hero; Nicki had made strides in hip-hop that put her well past her peers who were women rappers and many who were men, too. But she didn’t just let her accomplishments — multiple number one debuts, stadium headlining tours — speak for themselves; she made it a point to articulate her perspectives on gender, and they felt raw and important, at a time before social justice had become cool.

There was, for example, the infamous “pickle juice” clip, taken from the 2010 MTV documentary My Time Is Now, in which Nicki sits in some sort of dressing room, bright-pink hair piled atop her head like a Sno-cone. She stares straight into the camera and speaks extemporaneously: “When I am assertive, I’m a bitch. When a man is assertive, he’s a boss. He bossed up! No negative connotation behind ‘bossed up.’ But lots of negative connotation behind being a bitch.” It became something of a common refrain, an aphorism often batted around to signify the micro- and macro-aggressions women are all too familiar with. In 2012, she became embroiled in a feud with Peter Rosenberg of Hot 97, which she ended by saying to his face: “I don’t know your resume. I never found you funny. I never found you entertaining. I never found you smart. I just found you annoying.” Around the same time, almost as if in response to criticism of neon-hued, pop-adjacent releases like “Super Bass” and “Right Thru Me,” she began releasing some of her strongest music — the incendiary, commanding “Lookin Ass” and “Boss Ass Bitch,” for example.

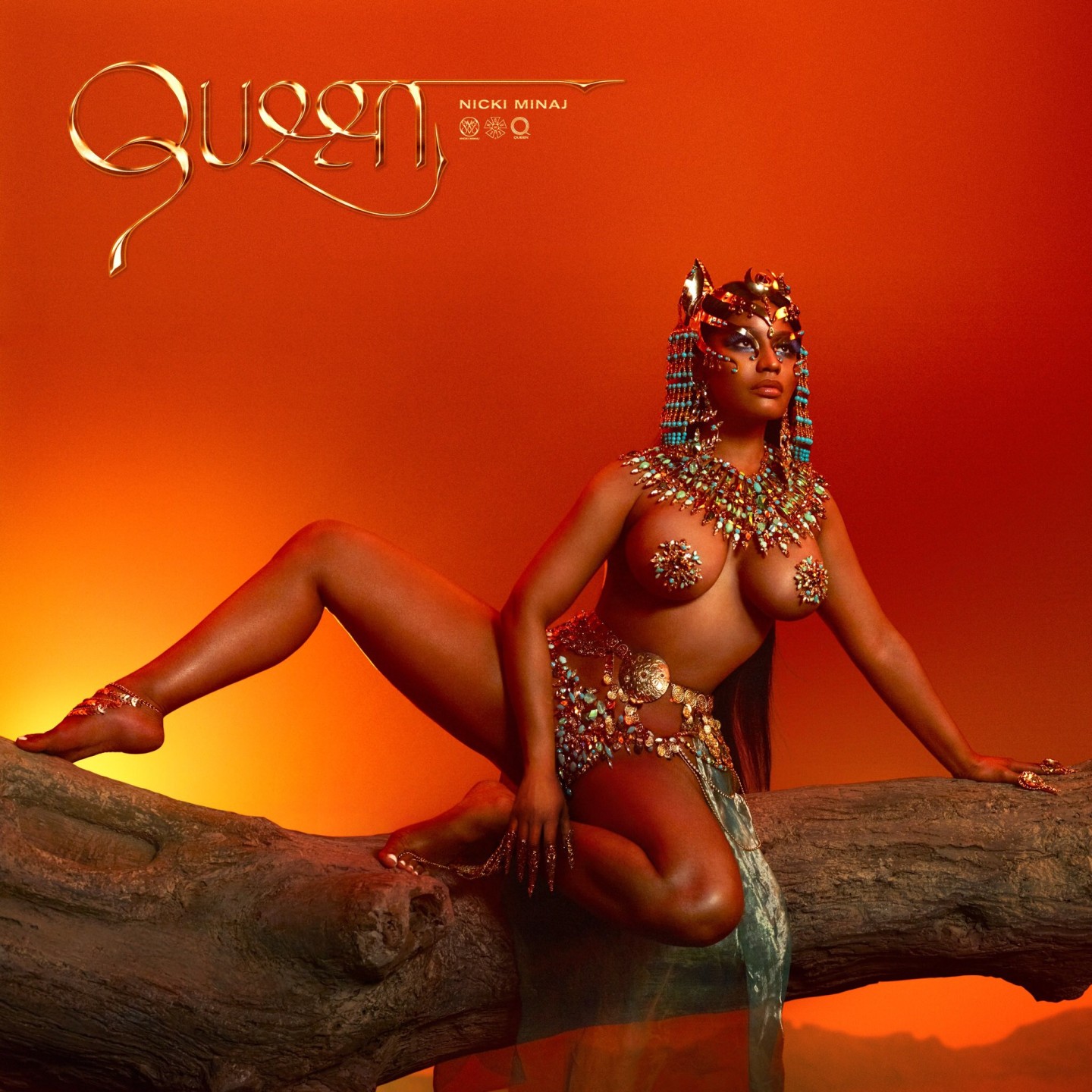

But in the years since, having established herself as a legitimate contender in rap, Nicki has shifted her targets from the gate-keeping men who dismissed her as “not real hip-hop” to the women rappers who may not have been made in her image, as she insists, but at least benefited from the path she paved. The very public beef with Remy Ma, the is-it-or-isn’t-it-a-beef with Cardi B, the endless references to the “bitches” who are “her sons.” Those anxieties are among the defining emotional characteristics of Queen, her fourth album, released last week after a months-long roll-out that has felt manic and marred by, well, drama. There was an angry DM sent to someone who criticized her on Twitter (Nicki has since said she “never responded to that lady”), a pair of bizarre appearances on Beats 1 Radio, and a social media back-and-forth with her ex, Safaree, that included claims of assault. (There was also “Fefe,” a disjointed collaboration with Tekashi 6ix9ine, the New York rapper who is currently awaiting sentencing on charges of using a child in a sexual performance.)

Unfortunately, the chaos that has surrounded Queen is present on the album, which does not live up to Nicki’s promises. There are flashes of the brilliance that landed her here, but, like the The Pinkprint and Pink Friday: Roman Reloaded before it, Nicki’s skill as a rapper is eclipsed by a lack of finesse and editing — something that is just as crucial to artists of her caliber as the physical making of music. At times, it feels like she has spent more time thinking about the people she perceives as being her competition than she has actually competing with them.

How can the person who made “Truffle Butter” be the same person who made “Anaconda”?

The narrative surrounding Queen, from Nicki and from critics as well, is that the album marks a return to her hip-hop roots. “I know it's going to be my best body of work... That's next on my bucket list — to deliver my fourth album and make sure that it's a classic hip-hop album that people will never forget,” she said last year. It’s a dynamic that has, unfairly to her, been at play since the early days of her superstardom. But as the overlap between rap and pop continues to grow, and as the tensions have eased between so-called real hip-hop and newer, more melodic sounds within the genre, this is an odd time to demonstrate a fealty to boom-bap. Worse, her interpretation of “real rap” gives in to some of the genre’s worst tendencies — cringeworthy battle rap punchlines and double entendres that feel like parodies of themselves. (Almost unbelievably, she rhymes “king kong” and “ding-dong” on two separate songs.)

No listener deserves to be subjected to the “awfully hot coffee pot”-type-verse Eminem inflicts on “Majesty,” the second track, deflating any momentum Nicki may have had with “Ganja Burns,” a straightforward introductory mission statement rapped over an afropop-adjacent beat. It doesn’t help that it’s followed by “Barbie Dreams,” a flip of Biggie’s “Just Playing (Dreams).” The song, which was quickly absorbed by New York radio, might have been perfectly fine as a SoundCloud loosie or a provocative Instagram freestyle challenge, but it’s cringeworthy as a legitimate artistic statement (“I used to have a crush on Special Ed/ Shout out Desiigner ‘cause he made it out of special ed”). And it encapsulates much of Queen’s ethos: It’s an album held together by platitudes, and lacking any real introspection or depth — either in subject matter or sound.

As usual, Nicki’s best moments come through when she’s experimenting, when it sounds like she’s not overthinking things. Towards the end of “Majesty,” an otherwise painful song, she delivers an inspired 40 seconds of a gently menacing lilt (“Jealousy is a disease, die slow, die slow, die slow”) that are far more inventive and captivating than much of the rest of the album. Later, on tracks such as the creeping “Hard White” and the heartbroken “Run & Hide,” she offers two best-case scenarios, one rapped and one sung. On both, she legitimately sounds like she’s enjoying herself — an intangible quality that is nevertheless detectable by listeners.

Few artists have a wider gulf between their best songs and their worst, and that is part of what makes Queen, and much of Nicki’s oeuvre, so frustrating. How can the person who made “Truffle Butter” be the same person who made “Anaconda”? On “Ganja Burns,” she barks, “Unlike a lot of these hoes whether wack or lit/ At least I can say I wrote every rap I spit.” That strikes as an odd metric: to be OK with being “wack” as long as you wrote the rap in question yourself.

It’s possible for multiple things to be true at the same time: Nicki Minaj has absolutely been subject to sexism and misogyny, in rap and beyond. But she’s also put out a lot of trite music. While Queen may be a disappointment of a major release, it’s worth noting that it would be totally acceptable from any top-tier ASAP member, Rocky or Ferg, for example — artists who exemplify the kind of songs that will always have a home on New York radio, even if they aren’t necessarily good. If the last few years have proven anything, it’s that many of rap’s most popular artists aren’t its best ones. For better or worse, Nicki has confirmed that she belongs on that list.