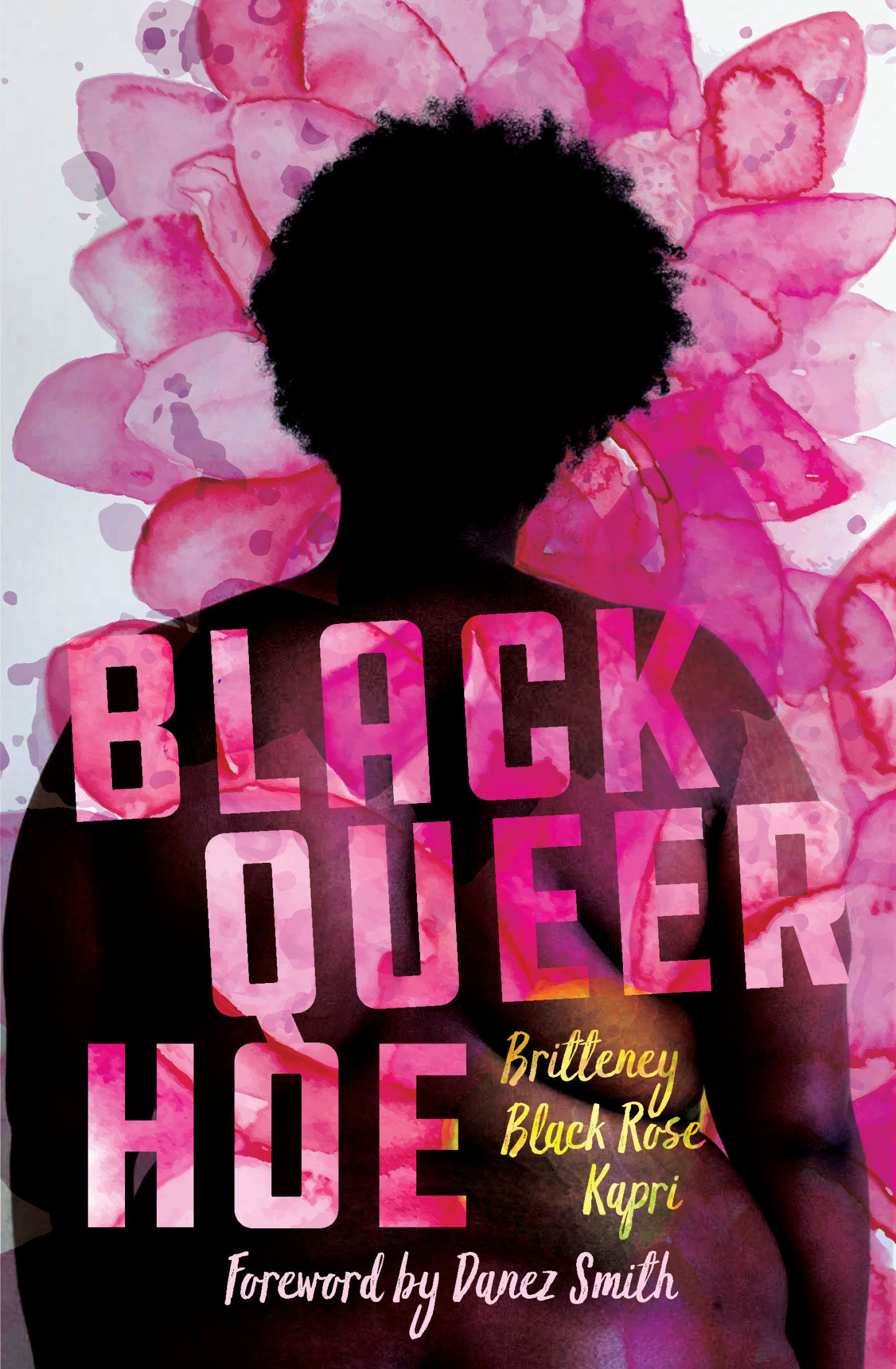

Britteney Black Rose Kapri is not interested in your bullshit. If you're not pro-Black, if you're not pro-queer, if you're not pro-hoe, then you’re not here for Britteney — and she’s not here for you. Kapri is a poet, writer, and teaching artist from Chicago. Her work explores Black women’s sexuality with a Black, queer, feminist lens. Her debut collection of poetry, Black Queer Hoe, is an invigorating exploration of what it means to live at the intersections of those identities. Though this is her debut collection, Kapri is no stranger to the poetry world. She is a teaching artist for Young Chicago Authors, her work has been featured widely, and she is the winner of the 2015 Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer's Award. We caught up about Black Queer Hoe, the meaning of femme, and being peak Chicago.

Give me a sense of how you grew up.

My mom is a middle school teacher, my dad is a lawyer, and I grew up with a shit ton of brothers and sisters. My grandmother is a former Chicago alderwoman of 20 years. I grew up in Uptown, a neighborhood on the North Side of Chicago. When I was younger, it was arguably the most diverse neighborhood in Chicago — a significant fact considering that Chicago's one of the most segregated cities in the States. For the earlier part of my life, I grew up with with a single parent, and then my step-father popped into my life. We've lived in Uptown my whole life. I moved out briefly — a terrible idea — and I moved back as soon as I could. It's my favorite place in Chicago.

How did you get into poetry?

When I was eight, I was in a hip-hop theater ensemble in the after-school program at my elementary school called Kuumba Lynx. From there, I got introduced to slam when I was 14, and I haven't looked back since.

The title of the book is a phrase you've been tweeting and talking about on social media long before it was finished.

Black Queer Hoe started off as a series of tweets — pro-Black, pro-queer, pro-hoe. Black women are always asked to sacrifice themselves for the "greater good." Black men ask Black women to sacrifice their womanhood for liberation, white women ask Black women to sacrifice their blackness for liberation, and no one wants anything from queer folks besides silence. I decided to make a statement about myself — my activism, my art, about anybody who interacts with me. If you're not pro-Black, pro-queer, pro-hoe, then you're not here for me. I decided to get it tattooed, then it became shirts, and then I realized that I've been writing these poems in this conversation around intersectionality, so I decided to name the book after that. Those three things are the pillars of my activism, curriculum, and art — of just every part of me that exists.

Your most recent tattoo is peak Chicago. How does Chicago factor into your work?

In Chicago, [directions are] grammatically, "out South", "out West", "over East" and "up North." It's an understood rule about our language. That's part of the reason why I got the tattoo: not only is it distinctively Chicago, it's distinctively Black Chicago. White folks don't know that. They still say, "The East Side doesn't exist, it's the lake," but that's because they ain't going to South Shore. That whole section of Chicago doesn't exist within whiteness. Not only do these places exist, but these places also have rules, culture, a base.

Black Chicago will always exist in my poems and my art. It's the only truth I know, the only life I've ever lived, the only way I can ever communicate with anybody. There are lots of things in my poems that aren't meant for outside people. I write for people that look and live like me. Chicago's never gonna be pulled out of my bones. We ride super hard for the city.

When did you come to that conclusion that this is the book that you wanted into the world, and why?

My mentor Kevin Coval had been telling me to get off my ass and work. I'd spent a lot of years being complacent with my art, and I wasn't really doing much around it. He sat me down and was like, "What do you wanna actually do?" l said, "Eventually I wanna write a book." He's said, "Why are we not doing it?” I didn't have an answer, so I started exploring what I'd like to do.

Originally, Black Queer Hoe was supposed to be a coffee table book of my tweets, as well as pictures of black women in various settings. I'm still interested in doing that, but I thought, "Why aren't I putting out these poems as one collection?" Haymarket was like, "We fucks with you. Let's do it." It was the push from a lot of people that care about me that was willing to call me out on complacency.

What I really like about the intro is when Danez [Smith] describes the poems as the “Black, queer, femme interior.” What does the “Black, queer, femme interior” mean to you?

I've never used the phrase and still don't. One of the poets I encountered at CUPSI, called me their “femme-hoe mother,” I was like, "Oh. That's my aesthetic." I am here to encourage baby queers, and I guess baby straights too if they want to live the extravagant life — to just be themselves. Whenever people use "femme" to describe me, I always feel strange, because I have a lot of masculine tendencies.

Even though I use "she" and "her" pronouns, I don't actually prescribe to too many gender things. I think people would call me "femme" because my nails are long and I wear lipstick, but my nails are long and I wear lipstick when I play football and video games. I understand why [femme] is used to describe me, but it's also limiting who I am. I contain multitudes. Since I was a little kid, I've always described myself as a grown ass man, for no other reason besides [being] bored with everybody else. My family calls me that, everybody recognizes it, and that's just who I am. I'm a grown ass man. I handle my shit. I'm the most responsible person you know. I also wear lipstick. I also wear heels. I'm a bad bitch with a fat ass and big titties, but I'm a grown-ass man.

“For a lot of people that I know, poetry, art, and music has always been hand-in-hand with activism, organizing, and grassroots movements.”

Do you have thoughts on this moment in poetry and where the craft is?

Across the board, young queer people are kicking back at gatekeepers — not only in poetry, but in music, particularly around independent artists and rappers who aren't just prescribing to what's been done before. For visual artists, social media has made it so that I don't have to have some white man tell me that I'm good enough. I am good enough, and these thousands of people follow me and believe in me, and hopefully will also like my book and come to my show. I'm so interested in where the craft is "going" because there's no one stopping us.

Dr. Imani Perry has said that Black Chicago literature is often interested in sociological conditions. In Chicago, there's a marriage between art and activist communities. What do you think that means for your work and place in that lineage?

Most people around my age that grew up in different art scenes in Chicago were mentored by grassroots organizers — all these people who were and are activists and are always talking about socio-political topics in their art and everyday life. For me, poetry has always been based on activism. I didn't realize poetry was written about nature and all that foo-foo shit until I got into high school and was offered a myriad of dead white men where I was like, "This shit whack." For a lot of people that I know, poetry, art, and music has always been hand-in-hand with activism, organizing, and grassroots movements. There was no other way to do it, and there are a million different ways to be political in your art.

I saw Hanif Abdurraqib tweeting that it's political to write poems about nature and be black because so many white editors are just seeking out black trauma for sales, numbers, likes, and retweets. Maybe you're just gonna get this poem about my fucking pedicure, and I deserve to write a poem about my pedicure. Learning where your art fits in this line of sociopolitical commentary, where to draw the lines, is a lot of what people are talking about and figuring out now. There are lots of things I that I love writing about, and I love writing about Blackness so much, but also I'm not going to keep sacrificing Black boys on stage for white people, for white money. That shit's exhausting.

It really is.

How do I have these conversations, and also educate my students on a need to talk about their experiences and all of the bullshit that's happening to them? Being young folks of color, or young queer folks in a city that's constantly criminalizing them, that is constantly colonizing them, that is constantly telling them they're not worth it? I want them to write their Black poems, I want them to talk about their schools being closed, I want them to talk about their trauma, but I also don't want them to keep sacrificing themselves for white gaze. If you don't feel appreciated when you get off stage, then I don't know how worth it it is.

There's a lot of times where I'm doing really heavy pieces around these topics in rooms of people that didn't give a fuck about me."Look at the little Black girl, she puts sentences together." It's like, "Nah nigga, I'm talking about my dead best friend." These aren't abstract theories. These are my actual real experiences. The younger we get, the more political generations are, particularly in Chicago. A lot of grassroots organizing in Chicago is being done by students I really look up to and admire. They're at the front line right now. The biggest thing is how do we do this and do it safely for ourselves, mentally and emotionally.

Who you're reading right now and who you're listening to?

I'm listening to Femdot. That's my G, he's amazing. Also Joseph Chilliams and Saba. I'm currently going through Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit. I’m reading Julian Randall. Hel just released a book of poems, Refuse. Citizen Illegal by José Olivarez. Obviously, Danez Smith, everything they puts out just makes me feel bad about myself. I think my favorite poet, honestly, is Hieu Minh [Nguyen]. Man, I would never say this to his face, because he's a shady bitch, but Hieu's actually my favorite poet. The way he talks about loneliness is probably the most seen I've ever felt.

Are there any young Chicago writers and/or musicians that we should be on the lookout for?

I'm gonna say this a million times, I think Femdot is one of the most talented young MCs. I’m also listening to Kaina. In terms of poets: Ari Appleberry, who is one of my youth poets; Kennedy Harris; Kara Jackson; Morgan Vernando; and Levi Miller. The things that they're writing — they were in my workshops this past weekend — are just so freaking good, it's ridiculous.