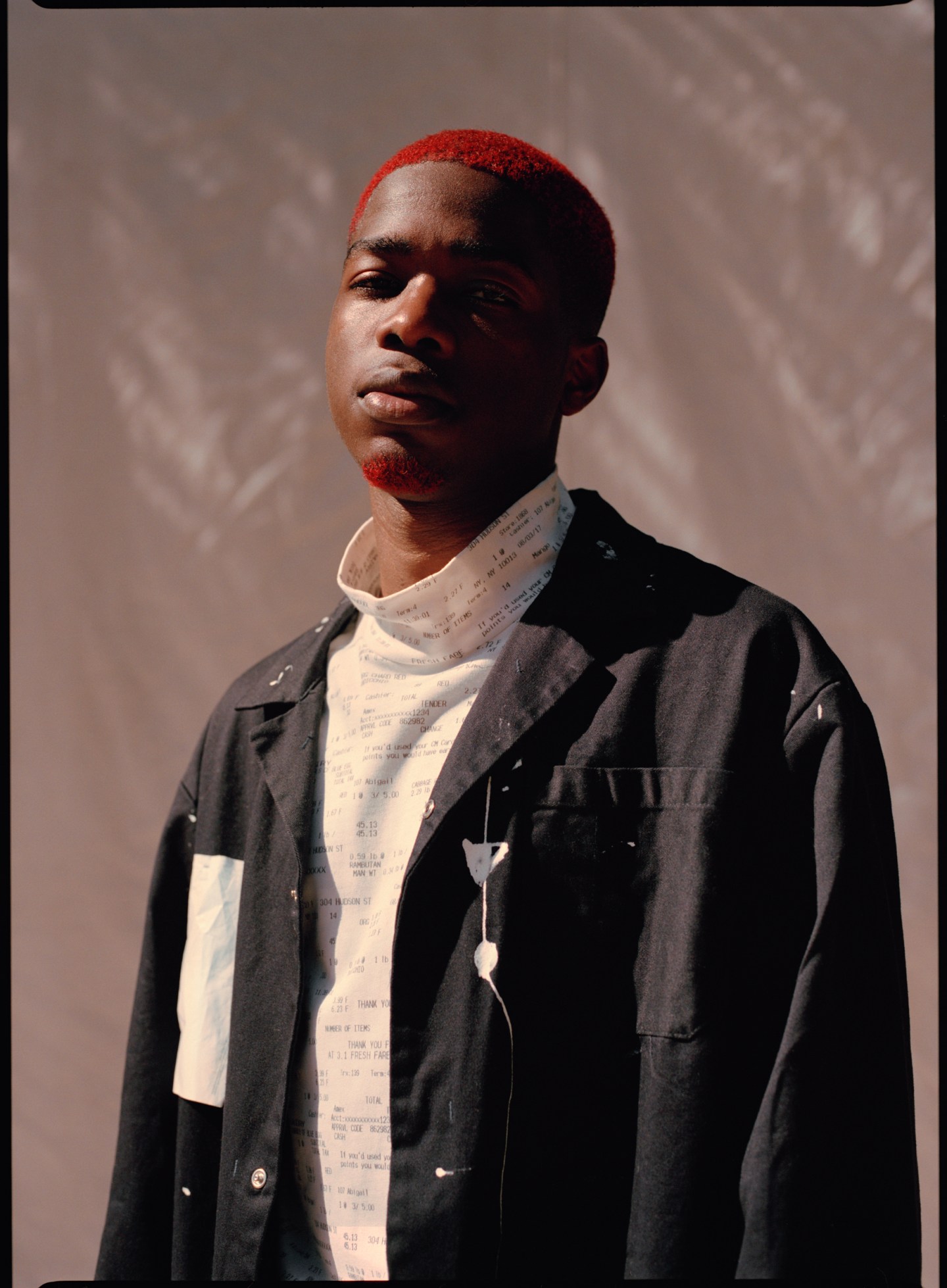

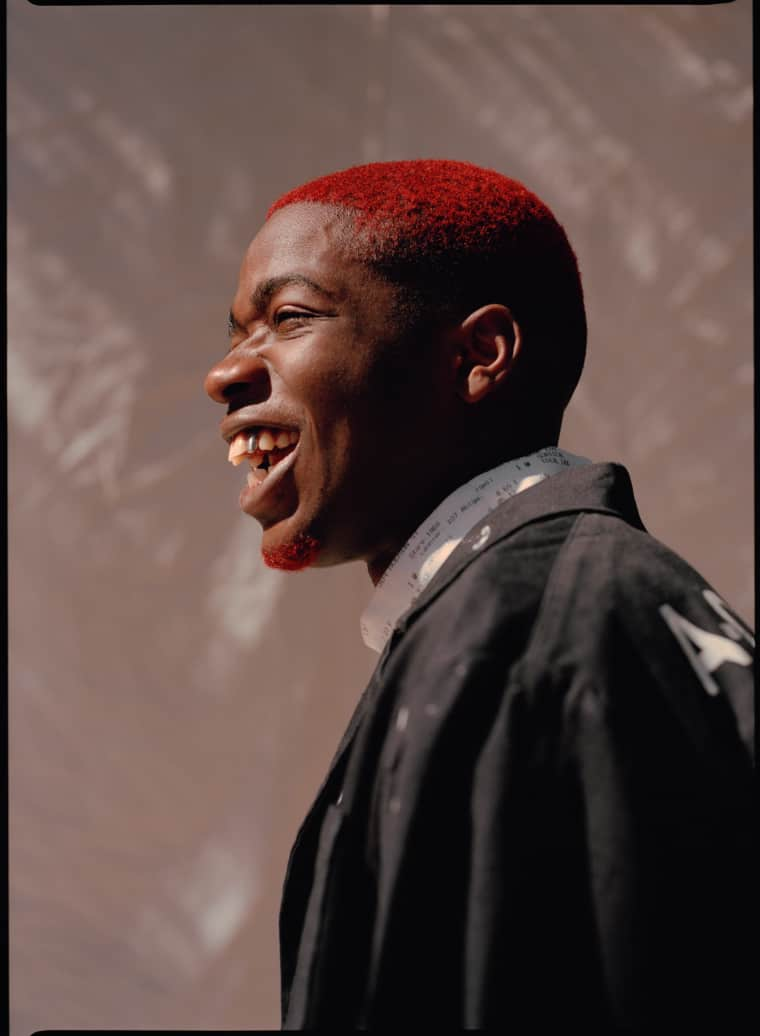

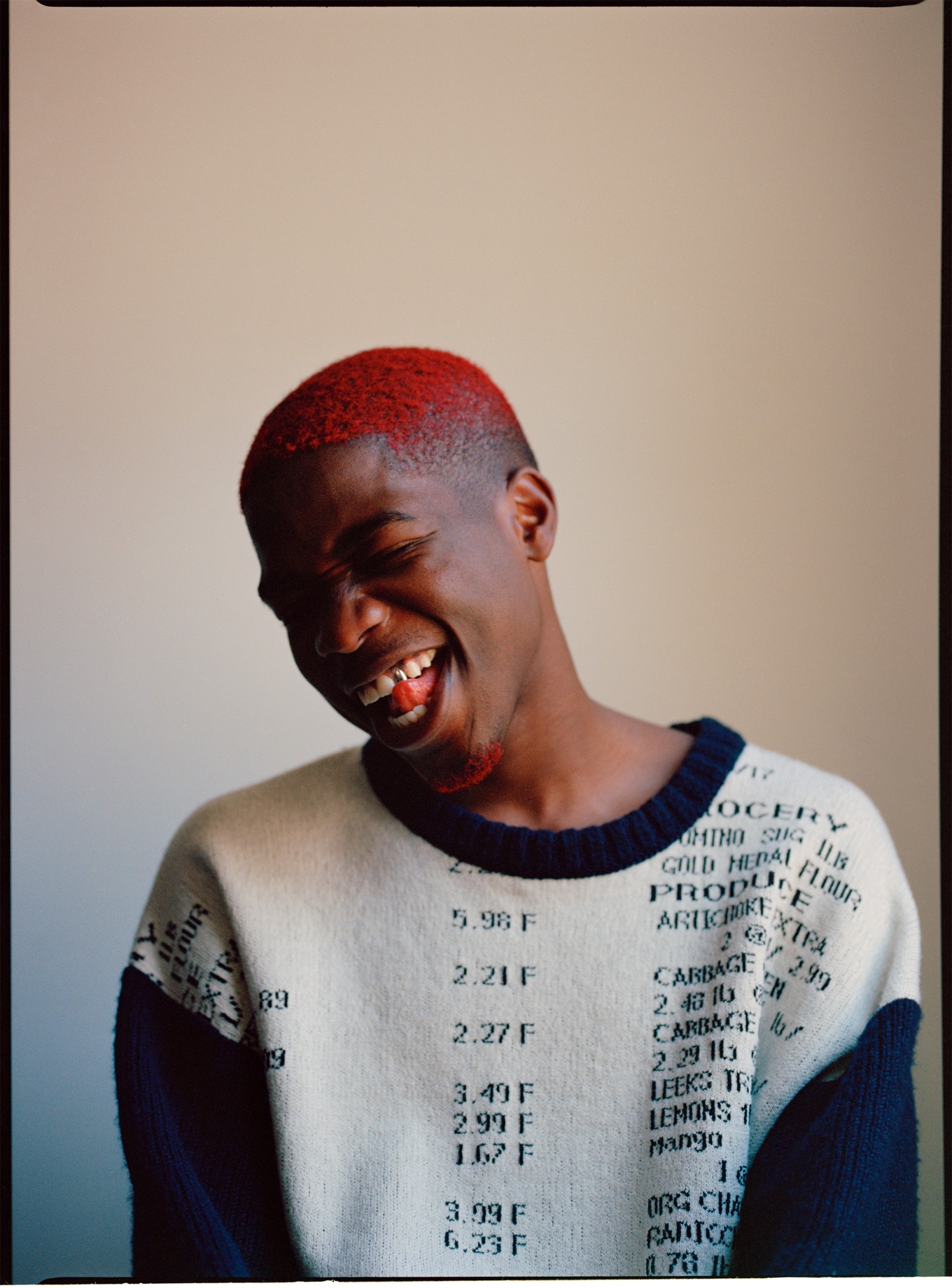

The physical transformation of Mohamed Sylla, a.k.a. MHD, has been one of the most fun aspects of following his career, his style carefully curated and derived from Parisian and suburban streetwear, Ivorian ambianceurs, and Congolese sapeurs. When he appears on a laptop screen for our interview on a recent fall day, his hair is dyed in a vibrant and near-cartoonish red. “Don’t pay attention to it,” he says, almost provocatively, with a smirk that reveals his golden teeth. “It’s just some crazy shit I did.” (By the time this story is published, his hair color will already be back to blonde.)

Sylla has a clean, child-like face and looks exhausted — or maybe it's just his perpetually sleepy-looking eyes. He's just arrived in New York to promote the release of his new album 19. The afro-trap video series that made him famous was almost entirely shot in the 19th arrondissement, one of the last bastions of Paris's working-class and immigrant populations. “We really thought we’d reach strictly French audiences at first," he states. "To see the way it succeeds overseas — it’s great, it’s nice to see that.” The lo-fi visuals flipped the style of the traditional Parisian postcard, introducing viewers to the corners, sidewalks, streets, and buildings that make up his native environment.

MHD is treated as a “phenomenon” in French media, decontextualized from the music legacy and history he knows himself to be part of. The sentiment of surprise that accompanies his rise — the feeling of witnessing a phenomenon — comes from the power of French culture erasing and revising what inevitably is. It is the very existential reality of second-generation children of immigrants that afro-trap embodies, their rhythm and gestures.

The sound that MHD has conceptualized isn’t new, in its ambitions at least; many artists before him, ranging from Passi with Bisso Na Bisso, Mafia K’1fry’s Mokobé, and Abd-Al Malik, have successfully mingled West or Central African styles with (mainly) hip-hop. And, of course, African artists on the continent have organically synthesized their musical heritage with the genre. The change that MHD offers is a less folkloric approach to African music — a context in which artists from the continent, as well as the internet’s precarious abolition of frontiers — have allowed afro-trap and its visual grammar to reach new audiences.

On 19, MHD pursues the aesthetic project of his previous self-titled album while quietly departing from it. “On the first project, we really worked on the afro-trap sound — it was more about setting an ambiance, a mood," he explains. "This second album was about taking inspiration from everything we'd seen and done during the tour. I didn’t see myself pursuing the afro-trap concept this time.”

With features including WizKid, Steff London, and Yemi Alade, one can sense on 19 that MHD's position has shifted. Over the past two years, he's toured outside of France: at Coachella, across the U.S., in the U.K., and in Guinea several times. He’s an international star now, with greater ambitions — and 19 represents a coronation, with a very prestigious guest leading the ceremony: Malian artist Salif Keïta who sings on the cinematic intro “Mansa” (“king” in various mandingue dialects). “We were supposed to work together on my first project," MHD says of the link-up, "but it was made in a such short period we didn’t have time to do it. For 19, he was the first artist we contacted, and I gave him the intro directly.”

On "Bravo," he boasts, “the little prince has become a king.” Many of the songs are guaranteed wedding classics; the romantic "Bébé," which features France’s number one fuckboy Dadju, could presumably be an inaugural couples'-dance song. The soukous influences (he cites Koffi Olomidé and Awilo Longomba as artists he admires) can be felt throughout the opus "Papalé, Moussa," and he flirts with baile funk on the great "Samedi Dimanche."

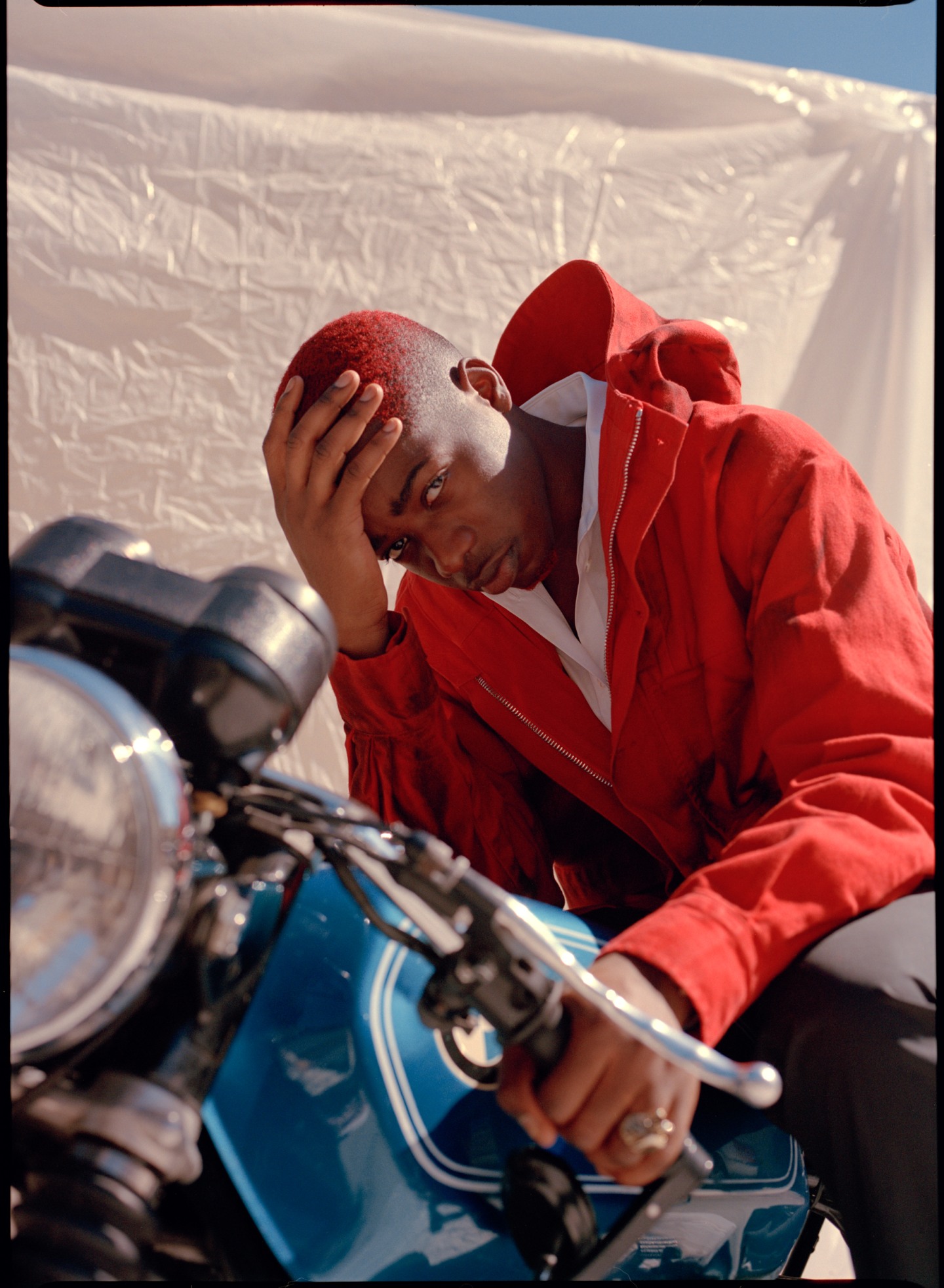

Success is a theme on 19, as MHD boasts about his achievements on "Bravo" — but the implicit ambivalence found in the lyrics of "Encore," in which he questions his longevity, shows the young man doesn’t take it for granted. “I still ask myself questions,” he says candidly. A few weeks before the release of the album, he posted a series of snaps in which he prefigured the end of his career. “Nothing strategic not here for a marketing move,” the white words over a black background read. “No one knows the hidden face of success it’s a lifestyle and it’s really tough to live like this…ending it all could make me feel better.”

That he posted it on Snapchat, a space that is simultaneously hyper-public and confined, make his statements both serious and volatile. As alarming these words can be, they are also the testament that MHD allows himself to be overtly skeptical and in control of his narrative. Nonetheless, with a newly-created label that's already signed Aulnay-based artist Topas, an acting gig in the upcoming movie Mon Frère, and a tour we that will begin in a few months’ new year, MHD seems here to stay, at least for a little while.