Photo: Kevork Djansezian / Stringer via Getty Images

Photo: Kevork Djansezian / Stringer via Getty Images

Should you ever doubt the corrosive racism and cruelty at the center of the system that Nipsey Hussle was rebelling against, consider the case of Kerry Lathan. He was the 56-year old friend of the deceased, who was also shot on Crenshaw and Slauson, and who is now behind bars for violating his parole. His “parole violation” reportedly meant going with Nipsey to the Marathon store so that the latter could buy him new clothes, a necessity after being freshly released from serving 25 years in the penitentiary. The generosity cost Nipsey his life and Lathan his freedom. He’s back in L.A. County jail, confined to a wheelchair.

This is who Nipsey represented in every bar and interview, every investment and strategic gambit. It’s why his death shook the city — but especially the neighborhoods south of the 10 Freeway — to their foundation. He wasn’t the only voice, but he was arguably the most clarion, crystalline in his vision, shrewd and compassionate in his execution. An inspiration to skeptics, a correction to doubters, evidence against all odds that the dream need not die. Then, gone. In front of the store that was the heart of his creative inception and ascent.

Hussle’s tragic demise refocused attention on the city’s southern land, its sects and secular traditions, the subtle depth of its underground culture and its capacity for violence — the latter of which often tragically overshadows the former. So if you’re trying to read about the blistering crossroads power of YG’s legendary Coachella set, you might get sidetracked by the headlines that fixate on the shots fired at his after-party in the early hours of Monday morning. No one was reportedly hurt, but TMZ doesn’t care about that, nor do the peroxide crypt-keepers at Fox News who laugh at songs like “FDT (Fuck Donald Trump),” scoffing at its blood simple efficacy in their neo-Klan code language.

After all, this nation has never handled nuance well. In the case of gangsta rap, the media historically stresses the cynical marketing points: the primary colors violence and vulgarity, the petty squabbles, and internecine feuds. It rarely highlights the deep cuts that examine the consequences, explain the circumstances that led to these life choices, and the tumorous regrets inherent. If a big enough rapper beefs on IG, your grandma will wind up asking you about it. But few outlets rush to cover the Thanksgiving Turkey drives or Christmas bike giveaways, or the artist’s umbilical connection to the historically disenfranchised and dispossessed communities that raised them. Jay said it best over two decades ago: “I'm from where the hammer's rung, news cameras never come.”

When YG took the stage at Coachella, a matter of hours after his close collaborator and friend was laid to final rest, it wasn’t a question of whether he’d pay tribute, but a matter of what form it would take. In various permutations, a viral tweet disseminated last week cautioned: there’s a Nipsey in every major city that you’re ignoring. There’s a seed of truth to that – chiefly that the media, usually based in New York, gutted by corporate greed, and usually low on resources or oblivious to covering hyper-local concerns, overlooks regional rap legends in favor of quick-hit blog posts on which snow-cone flavor Kanye dyed his hair this week. Or the blow-dried and botoxed sentient teleprompters of local news who scarcely cover inner-city concerns unless they can exploit a scene with yellow tape and a chalk outline.

Of course, there could only be one Nipsey because there could never be two of anyone worth revering. If Nipsey was sonically molded in the tradition of classic West Coast gangsta rap, he was an original personality, a spiritually and ancestrally attuned, biblically bearded Rollin 60s computer nerd who could rap with ballistic force, and balance capitalist savvy with philanthropic compassion. His closest peer was YG, not because they sounded alike, but because they were cut from different colors of the same cloth. For the last decade, YG and Nipsey grew up in the public eye, transforming themselves from super raw children of the struggle to symbols of aspiration, entrepreneurs, and avatars for the city itself. If neither got the national respect they fully deserve, they’ve been L.A. living legends since the last Lakers championship.

Still, no matter what the radius clause dictates, Coachella isn’t LA. Depending on where you stand, it can be a cross-section of some of the city’s worst stereotypes. Transplant influencers turning the Ferris Wheel into a backdrop for duck-faced flexing. Industry glad-handers in the all-access section loudly squawking about how this year’s excuse-to-do molly EDM DJ du jour is a genius for mixing “Old Town Road” into Kid Rock’s “Cowboy.” But for an hour on Sunday night, YG turned the Sahara Tent — a terrordome where souls go to die — into one of the most poignant, life-affirming musical tributes I’ve ever seen. A validation of the blunt power of place and identity, resistance and cultural legacy, a radical declaration of unity amidst stark differences in a place a galaxy away from Crenshaw or Rosecrans.

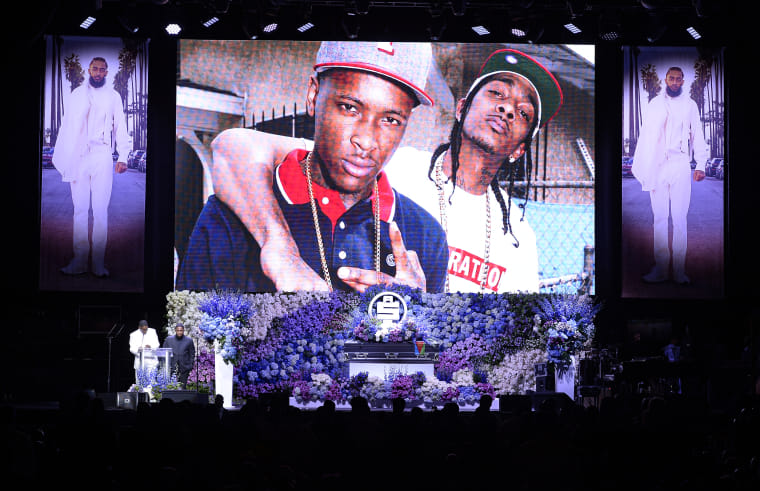

There was Nipsey, invincible in old video clips booming on the jumbo screen. Nipsey and YG in a photo snapped on the set of the “Bitches Ain’t Shit” video — 2011 — looking eerily like a young Snoop and 2Pac, and now, just like that original iconic L.A. duo, only one remains to carry the weight. Nipsey doing radio interviews and testifying to the value of owning assets, pledging to take care of his people. Footage of spontaneous memorial tributes in Detroit and St. Louis, Columbus and Harlem, Washington D.C. and Houston and Ethiopia. It gave way to his body levitating into a bed of clouds and a winged, beatific, and white bandanna’d 2Pac angel bestowing Nipsey with wings. It dissipated into final words from Nipsey himself, offering encouragement to keep working hard, believe in yourself, keep your heart pure, stay inspired, and love your people.

What may seem maudlin when read on an iPhone screen is actually real life; that’s what gives Nipsey and YG’s music such sizzling voltage. As it stands, there’s an alternate reality where YG isn’t still breathing. He could’ve been murdered in a 2015 shooting outside his studio in upscale Studio City of all places — the enemy had obviously been tracking his movements. YG survived to drive himself to the hospital. The cops described him as being “very uncooperative.” So don’t mistake any of this for cartoonish hedonism and violence created for suburban consumption; these are sectional anthems for the block first, then the city, the coast, and then everywhere else. And if you don’t understand, then go listen to YG’s “Don’t Come to LA.”

“Nipsey Hussle, I love you!!! This is for you!”

YG sets it off, his voice already a hoarse bellow and drowned in tequila, which he admits is the only thing that gave him the ability to be out here. “BPT” bolts out the speaker. There is Keenon Jackon in a black leather vest and a red bandanna, red pants, white shirt, surrounded by a bunch of homies from the set, blood-walking on stage and addressing the crowd as “Bochella.”

A song like “BPT” translated to casual listeners as just another Mustard and YG banger, which was part of its genius. The track uses vernacular storytelling about his early years coming up on 400 Spruce Street, Westside Compton. This is Tree Top Piru turf, the set that also spawned DJ Quik, making it arguably the most creatively fertile block in rap history. YG disses fake rappers, interpolates Dre’s “The Watcher” for the historical record, shouts out Nipsey, Game, and Kendrick, locating himself squarely in this lineage. Then he explains the brawl that got him put onto the set.

Rappers like YG and Nipsey are kryptonite to critical language. They’re rappers who you instinctively feel — not necessarily through identification with their story, though they’re able to forcefully convey a sense of uplift and determination that cuts across race and class divides. But it’s music that so deeply mines the unspeakable feeling that comes from growing up in Los Angeles or zealously adopting it as your own. If the internet is inherently destabilizing, lending itself to a rootless disembodied sense of place, this is innately grounding. It’s in the rhythm and slang, the way that the nervous synthesizers somehow soothe the back of your brain, the drums that reflexively make you want to roll down the nearest window. Some real L.A. shit; sometimes there’s no other way to say it.

From there, it bleeds into “Twist My Fingaz,” a civic anthem so specific that it could never really make sense east of Las Vegas. Terrace Martin’s vocoder crunch resuscitates the spirit of Roger Troutman, and YG raps like this was his birthright, which it was. Coachella has booked Kendrick and Schoolboy Q before, but this is something entirely different. Those are mainstream superstars whose music and identity are intrinsically tethered to the West, but their music has become worldwide pop. If Kendrick is a Dr. Dre, YG is a DJ Quik — not just via affiliation but because their creations are a litmus test. If you don’t know the words, you can’t really be from here.

“Me and Nipsey used to talk about doing Bochella for years,” YG tells the crowd. “He called it Coachella but I called it Bochella.”

It’s an offhand line that speaks to the dividing lines drawn by the industry and festival bookers. Artists like YG don’t get Grammys, which was why it was so momentous when Nipsey got his nomination. You might get booked to headline an “urban” radio station concert, but there’s a tacit double standard that these billion-dollar corporate festivals only book street artists when they’ve crossed over the realm of the safely respectable. By contrast, YG’s last album was called Stay Dangerous. It was a mission statement, not an idle mantra.

Getting on the major festival circuit can mean millions of dollars over the course of a career, money often directly funneled back to underserved communities — including the rapper’s immediate family, day ones and incarcerated friends. Artists like YG and Nipsey Hussle or a Mozzy or a Boosie, (at least theoretically) force outsiders to confront issues of police brutality, endemic racism, and savage political and economic inequalities. Until now, none of them had played Coachella. And while the teal tanktopped bro in the backwards Sigma Chi hat inevitably didn’t get it, it couldn’t have hurt for him to hear “FDT” at ear-splitting volume — especially when preceded by a pitch-perfect Trump impersonator who spewed racist invective at the crowd, puncturing the carefully curated and heavily filtered bubble of the festival grounds.

“We just lost one of our greats… one of our homies… a legend… black muthafucking Jesus,” YG says, catching his breath. Crammed underneath this baking metal shell, a neon mob of 10,000 clutches onto every word. “But like Nipsey said… the marathon continues.”

YG tears into “Suu Whoop,” a slab of sinister post-ratchet dance music rooted in Blood slang. Slightly winded, he compensates for the lack of breath control with a Game 7 energy, fatigued but ferocious. A full decade into his career, YG has become a deceptively excellent stylist, using negative space to maximize conflict, effortlessly switching tempos mid-song, and contorting his natural all-time great growl to play multiple characters. In “Suu Whoop,” he alters it to imitate a nuisance who interrogates him: “Don’t you got a daughter?” he sneers. “I’m a gangbanging ass dad.”

Afterwards, he acknowledges the difficulty of grappling with Nipsey’s death and asks for more tequila. Taking a huge gulp, he detonates into “Handgun,” a slashing double-timed stomp of homicidal keyboards and aggressive barks. Frenzied black and white clips of mosh pits and sadistic drill sergeants and prison riots and skinheads send the tent into near pandemonium. It’s easily the hardest gangsta’ rap set in the history of Coachella; 30 years after Straight Outta Compton terrified the white establishment, YG makes Eazy E’s hallowed villainy proud, lifting the curtain on the inner-city realities with humor and pathos — even if the prevailing aesthetic switched from Locs to tiny sunglasses.

There are the hits that earned YG a national fanbase: the Jeezy and Rich Homie Quan collaboration “My Nigga,” the Drake feature “Who Do You Love,” and his cameo on Jeremih’s “Don’t Tell Him.” The crowd sings every word to “Toot It and Boot It,” the slightly dated but sleazily beloved nursery rhyme that ensured YG’s career would extend beyond the jerkin’ era. He raps his remix to “Thotiana” and two-steps to Lil Jon’s “Get Low,” which seems like a weird choice until you consider that it was YG who figured out how to bridge a 21st century southern bounce to the classic L.A sound. His resume is incomparable: he went from the breakout act of the jerkin’ era to pioneering the ratchet sound that dominated the city circa 2012-2014, then he futurized G-Funk for Still Brazy and dropped the defining political rap song (“FDT”) of a generation. For his final act of the night, he brought out 2Chainz and Big Sean to perform “Big Bank.”

But the most indelible moments were the ones in memoriam. The sound of his voice cracking as he considered the loss of a brother, the impassioned triumphal guarantees that the marathon will continue. He unexpectedly dusted off two West Coast classics from the turn of the decade that never traveled more than 300 miles inland, the raunchy Chronic homage “Bitches Ain’t Shit,” and “You Broke”. You wouldn’t expect a Coachella audience to know every word, but some things are permanently ingrained. Suddenly, the crowd seemed transported back to barely remembered functions and house parties and stoned late-night YouTube binges soundtracked by YG and Nipsey. And, of course, there was “FDT,” with its magnanimous plea for racial unity to collectively war against legitimate evil.

Yet the most powerful moment came during the quietest part of the entire festival. Midway through, YG asked the crowd for a moment of silence, and for nearly a minute, no one uttered a syllable. The screen was lit up by a sea of blue candles; the only thing audible was the muffled sound of tears. In this momentary void, it seemed as though the voices from outside this echo chamber had finally received an important chance to be heard — and you could hope, against all odds, that what they had to say wouldn’t soon be forgotten.