Photo provided by AfroFuture Youth

Photo provided by AfroFuture Youth

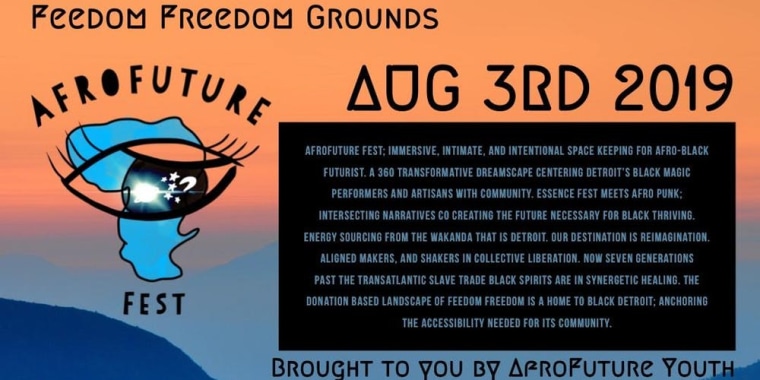

When Detroit-based non-profit organization AfroFuture Youth launched an online fundraiser for their forthcoming AfroFuture Fest, their goal was to raise money to start programming with local teens that’s centered around providing resources and spaces to co-create a future they want to see. The festival, which is scheduled for Saturday, August 3, began trending on social media last week when their ticket structure — charging white people $10-$20 more than people of color — was announced.

The story gained headway when local Detroit rapper Tiny Jag, who's real name is Jillian Graham, publicly pulled out of the festival because the pay model did not reflect her views and was "emotionally triggering.” In an interview with Detroit Metro Times, Graham said she was immediately enraged because she's biracial: "I have family members that would have, under those circumstances, been subjected to something that I would not ever want them to be in ... especially not because of anything that I have going on."

Before the headlines, the organizers of AfroFuture Fest — Adrienne Ayers and Franchesca Lamarre — were involved in creating and cultivating intentional spaces focused on black youth and teens, and conceptualizing and curating art that practices power over autonomy. Since 2014, Ayers has cultivated spaces for black youth through acting as the co-lead organizer for Black Lives Matter Detroit for two years. She specifically lead the protests against the death of Aiyana Jones in 2016 in Downtown Detroit. Lamarre, who is also known as Queen Complex, is an Afrofuturist, conceptual artist, and curator whose work focuses on embodying "queendom" to address and dismantle white complex systematic-oppression. The two joined forces this year to begin working towards building equitable futures for black youth and the African diaspora through the organization.

After Tiny Jag’s interview, Ayers and Lamarre responded to the online discourse around the event via their Eventbrite page, saying the pay model was more about establishing equity, addressing the wealth gap, and about access to affordable entertainment than about race. As the story continued to travel, Ayers says she began receiving threats and harassment on her various personal and professional social media pages from "white supremacists and white people". The backlash led her to close commenting on her Instagram posts and, ultimately, to change the pay model to $20 general admission, with a suggested additional donation from white concertgoers.

Before they changed the pay model, Eventbrite released a statement saying their company doesn't “permit events that require attendees to pay different prices based on their protected characteristics such as race or ethnicity.” Eventbrite told CNN they "notified the creator of the event about this violation and requested that they alter their event accordingly." If the organizers did not comply, they said the event would be unpublished completely from their site. The legality of AfroFuture Fest’s pay model also came into question because it is indeed illegal to charge different prices based on race.

During a recent phone conversation, The FADER spoke with both Ayers and Lamarre about their intentions behind the pay scale, the importance of equity, and the youth that the festival was intended to support.

In a tweet, you mentioned that you and the owners of Freedom Freedom were receiving threats from white supremacists and this is why you altered the festival’s pay model. Can you talk more about when the threats started and what it was like coming to the decision to change the ticket structure?

Adrienne Ayers: Safety was the first thing that popped in our head. There were white people in our messages calling us the N-word, telling us they hope the kids die from cancer, calling us fags, all of the things. I closed the comments on the AfroFuture Youth page so the kids couldn't see because racist comments were coming in and harassment. It doesn't help that Fox News shared what school I go to and what my major is. So, for my own safety I didn't go to class last Tuesday. Harassment is the main reason we changed the ticket structure because the kids don't need to be subjected to that and once Mama Myrtle [the owner of Freedom Freedom Grounds] started getting actual phone calls and [Franchesca] and her mother started getting harassed, it's like for safety sake, especially because we just had Nazi's walking the street in Detroit a few weeks ago.

Franchesca Lamarre: Our decision was based off of continuing to create the spaces that we need as a community and making sure that while we are creating these spaces in the community, that no one is harmed or further harmed. So, because it became unsafe — because of white bodies co-opting the space that we centered for blackness — it was only necessary to change our structure.

What were your reactions when the initial story went national?

Ayers: My initial reaction was, I expected a lot of white people to be upset, but seeing a lot of black people upset too let me know that, okay, these conversations need to be had. People out here claiming that they ready [for reparations] — although this wasn't us trying to put something out there specifically for reparations. Although, it [equity] is similar to that; you can look at it like that if that's your interpretation of it. But I just want to know how people are out here trying to have these discussions outside of this situation about reparations and about these things, but when situations like this are presented are upset. It's like are we really ready?

Lamarre: I initially was thinking about proximity to whiteness and how that can get you attention in certain ways. If we want to think about the person [Tiny Jag] that has stirred up all of the media smearing. I feel — and this is subjective — I feel that this wouldn't have gotten to the level and extent that it had if it wasn't a support system fixed for her to have her voice heard in this way. Again, we wanted this to be for us and by us. We wanted it to be small. We wanted it to be about Detroit. We wanted it to be about the east side.

What was your intention behind the pay model? Do you think this goal was accomplished?

Ayers: The intentions behind the pay model was to create an equitable framework apart of the work that we were already doing...because of the wealth gap. Specifically, because we don't have access to spaces as black and brown people because white people so often co-opt spaces and take over spaces. So, I still feel like the goal was accomplished. Black people still are centered by coming to this event, this is an Afrofuturist pro-black event. We are still asking for suggested donations from white people which is still uplifting equity. It's still saying, even if it's not making them have to pay the money, this donation is suggested and this is something that you should do. This is something that you need to be apart of monetarily to redistribute power, and understand that things are set up in a way that is not equitable.

Lamarre: The intentionality behind the pay model, again, is in alignment with the work that we see necessary as far as our program for AfroFuture Youth: co-creating and building these equitable worlds so that all aspects of black life can thrive. So, what are the aspects of black life that are not thriving right now? We don’t have access or we can't afford the food that's in our community. So, there's a lack of access to affordable food and a lack of access to education. We don't have access to affordable events in our community. Again, the ones that are in our community are co-opted by whites and priced out and bought out. The events and the culture that we create and build here is bought and sold back to us at a higher profit. So, definitely, there was intentionality behind the ticket structure. We wanted people who had privilege to be able to give something back, pay it forward.

Can you talk about your work with AfroFuture Youth and how you foresaw AfroFuture Fest benefiting the non-profit organization?

Lamarre: AfroFuture Fest was directly influenced by the funds we need to start programming. We were trying to think of creative ways — myself as an artist and curator — I used my skills in that department to think about what are the things that I see black people, people of color in the city need as far as artists. They need a platform to be heard. The spaces and the venues that we are afforded in the community are not ones that are black-owned or upheld by black people. We just lost the Baltimore Gallery, which was a black-operated space in the most gentrified area of downtown right now, the Midtown area. So, we wanted to give the community that space to be themselves and show up in whatever intersectionalities that they have.

If you could change anything about how all of this unfolded, what would you change, if anything?

Ayers: I want to say nothing. I don't know what else to say.

Lamarre: I think that it didn't help to have the outside community, as far as people not of color. People that aren't in Detroit specifically. People who aren't engaging in the community from our level, from our first-person experience living in the city. I've lived in Detroit all my life. So, if we had a better way of sharing ideas and opinions amongst the community first, that is what I would change about this.

Moving forward, what do you want the world to know about AfroFuture Fest, AfroFuture Youth, and your work?

Lamarre: I just want people to understand that it's been a year of us trying to start programming and it shouldn't take controversy for people to care about black kids. It shouldn't take controversy and issues for people to think twice about black kids. I need people to understand that the work that we are trying to do is intergenerational. I want people to understand and value themselves in their blackness, however that shows up. I want people to understand and realize that it's okay for us to need spaces that don't center whiteness. It is okay to want a space for ourselves. To be in that space, to feel whole, to feel celebrated, to feel free so that we can, in turn, heal.