In 2005, shortly before the release of Silver Jews’ fifth album Tanglewood Numbers, The FADER’s Nick Weidenfeld spoke to the band’s lead songwriter and singer, David Berman. It was the first time that Berman had ever given a lengthy interview and the first time that he had talked about the 2003 suicide attempt that almost ended his life.

Berman died yesterday, August 7. He was 52. You can read Tal Rosenberg's obituary for the late artist here.

This article originally appeared in The FADER issue 31 under the headline Dying in the Al Gore Suite.

David Berman died November 19, 2003. It had been three years since he'd released his fourth album under the moniker Silver Jews. It had been more than four years since he'd published a critically celebrated book actual air, which, as contemporary American poetry goes, was incredibly popular. And it had been 16 years since he'd attended University of Virginia, where he'd met Stephen Malkmus and started playing songs on friends' answering machines. "When I was 23 and he was 24, I got to watch [Malkmus] become famous," Berman remembered of Pavement's success. "There were these really cruel people that I knew, just unlikable people, and he would explain they were likable. I would say you don't know. You can't know! The only way you can judge a person is how they treat someone they have nothing to gain from. And everyone has something to gain from you." Over the years, Berman grew increasingly dubious of fame — how celebrity and fandom confused fact and fiction, how it disconnected the self from reality. And though Malkmus, Steve West, and Bob Nastanovich often played with the Silver Jews, and the Silver Jews were even misnamed "a Pavement side project," the Silver Jew himself did not become famous.

It was not that Berman was without fans. In 1992 — the same year Pavement released Slanted And Enchanted (a title based on a Berman cartoon) — Kim Gordon included the Silver Jews' first recording The Dime Map Of The Reef in her year's top 10 for Rolling Stone. During the nineties, Berman's fan base grew larger, cultish, and precious of his art. Yet he made few public appearances — mostly small poetry readings or academic lectures. He refused to tour. He rarely played live or spoke to the press. "I live on an island," he said, speaking of his house in suburban Nashville where he moved with his wife, Cassie, and dog, Miles. As he told his mother, "If they told me I couldn't leave the radius of six miles from my house, I really wouldn't care. There's nowhere I really want to go." Especially in the years following the release of his last album Bright Flight in 2001, Berman was not seen or heard from. For his fans, a Silver Jews album was not just a milestone in music, it was their only reminder that David Berman existed.

It's not surprising that no one heard what happened that morning, two years ago. How Berman woke up and overdosed. He'd overdosed twice before. This time, however, it was intentional.

He set out to take 300 orange Xanax, ten at time, between house chores. He brushed his teeth, took ten pills. He made the bed, took ten pills. He showered. He walked Miles. He got the mail. Then he stopped remembering. What must've happened in the next few minutes or hours was that Berman grew incredibly romantic. Like the most honest but self-consciously histrionic moments of his writing, he stumbled to his closet and put on his wedding suit. He tried to scribble some final words. "Cassie I'm sorry. I can't take it anymore. I love you." Then he called his crack dealer. His dealer picked him up and brought him to the place he'd ostensibly been living the past year and half.

The crack house also doubled as a music venue, and when Berman showed up, a vile Frenchman was performing, the kind of artist who shits on crosses. Against the Xanax, the crack was uplifting. Berman was like a plane just taking off, gaining enough energy to barely walk. Then his wife showed up. Cassie had found the suicide note and her husband gone. She'd called his dealer and was there to take Berman to the hospital.

He screamed at her the whole cab ride. He'd never liked being told what to do and he did not want to be saved. Cassie couldn't make the hospital guards take him unwillingly, so she asked him what exactly he wanted to do. He told her to take him the Loews Vanderbilt; the same hotel Al Gore holed himself up in November of 2000. Three years earlier, the Vice President had traveled to Nashville to make his concession speech, but when questions concerning the Florida ballot arose, Gore waited. And waited. He stayed in his room for two weeks, while camera crews from around the world lined West End Avenue, hoping to get a shot of the VP passing his hotel window.

That's what Berman was thinking about when he approached the front desk. "Give me the Al Gore Suite," he demanded. He must've been a sight in the lobby of Nashville's nicest hotel, overdosing on crack and pills. But he was wearing a Brooks Brothers suit, and they gave him the room. Riding the elevator up to the eleventh floor, Berman laughed at the bellboy, "I want to die where the presidency died! So he stumbled down the hall, opened the doors to the Al Gore suite, and did just that.

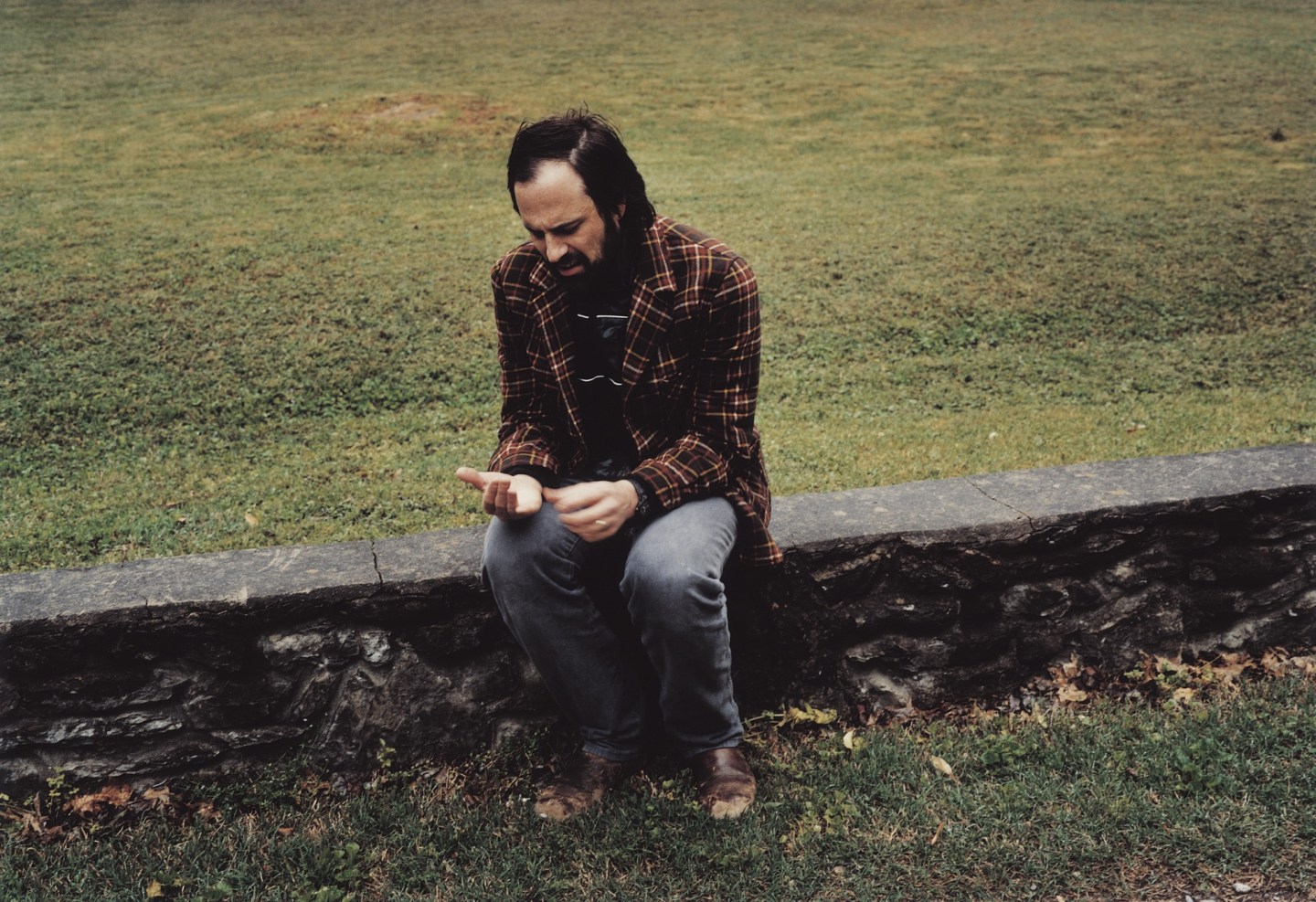

It was a year after his suicide attempt, after he'd woken up in the psychiatric ward of Vanderbilt hospital, that Berman decided he was dead. He explains all this, standing in his backyard, holding Miles tightly by his leash. It's raining, and the grass needs mowing. His mom and his wife are inside, tearing down old wallpaper. It feels like a scene stolen from actual air. He twists the dog leash around his hand tightly as he explains how disgusting and unethical it was that he'd left such a pathetically short note for Cassie. He tightens the leash even harder when he describes the feeling he had when he woke up in the hospital three days later. He pulled the tubes out of his body. He didn't want to be alive. But he was — at least he thought he was. And he was convinced to check in to the Hazelden Foundation, one of the country's oldest rehab centers. Two of his close friends had recently OD'd, and maybe it was sinking in because when he'd checked out of Hazelden 20 days later, he was happy. And he was sober. He bought a house in the suburbs and started going to temple more often. But it was at synagogue, during Yom Kippur service, that Berman realized he was dead and had been for over a year. Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is a lonely, painful day. It is about regret and self-doubt, and for Berman, sitting there, praying and pining over years of sin and remorse, he concluded that all the good that had come to him over the last year couldn't have happened. After overdosing, he'd never woken up in Vanderbilt Psychiatric. He'd never been convinced to go to Hazelden. The last year was a lie. All that good stuff was fake, an illusion. He was dead.

Listening to Berman explain all this as he takes his daily walk down Tanglewood Drive, you ask yourself, How in the world does this happen to someone? How can a man fall this way?

There is a thread, a word, that runs through Berman's confession. He often describes himself as "solipsistic" and it is this quality, a lack of empathy — an inability to relate to the environment — that may explain Berman's predicament. Suicide, they say, is the most selfish of acts. This may be true, but not in every case. There is a fine line between selfishness and solipsism, the latter more pathological than malicious. And Berman is solipsistic to the bone — someone who cannot comprehend a world outside of the self. This may be the real reason he doesn't tour. "I still believe in putting something out and not asking people to buy the record, then buy a ticket to my show and then buy a t-shirt and then a, like, copy of the show they just saw on CD," he says. "That's undignified to me." But don't his fans want to pay to see him perform? Would they mind a live recording? Finding that middle ground requires empathy, and Berman didn't tour. Instead he retreated even further into himself. For a year and half he had little contact with the world. Like Conrad's young apostle who's lost at sea — "But the truth was, he died from solitude, the enemy known but to few on this earth, and whom only the simplest of us are fit to withstand" — Berman, shacked up in a Nashville crack house, was losing "all belief in the reality of my action past and to come," as he put it.

A few weeks after that Yom Kippur service, after he concluded he was dead, Berman started seeing his rabbi and studying the Torah. "I've never been from a certain group." he says of his recent attempt to connect with the world around him. "I've always reserved a space for myself where I'm unattached to any group, but the part of Judaism that I really take away, that means something to me, is the part about community." Identifying with a religious group is one way to battle solitude. Another way may be doing the press he had avoided his whole career.

This is the first extended interview Berman has ever given, and for the last three days straight Berman has talked, rarely pausing. The tone is confessional, as if Berman is finally giving something up, something he'd kept only to himself. But he's not doing press for himself. Without a hint of solipsism, he explains why he's doing interviews: "It has to do with trying to be a better person and not being such a fucking nightmare for everyone. It's about increasing the general happiness. Making it easier on people at [record label] Drag City. Making it easier on my wife. Making an effort."

Increasing the general happiness.

There is a pad of paper next to Berman's TV that reads the same message. He must remind himself of this constantly, and it seems to be working. "I used to consider myself weak," he admits. "Up until a couple of days ago, I would've had to count myself as a loser by my own yardstick. At night when I have dreams, I lose almost always. I'm being betrayed, or left behind, or somehow losing the game. One of the first things I do when I wake up every day is remember that I'm not really losing."

Tanglewood Numbers, which Drag City will release this summer, is Berman's first album in almost five years. It doesn't sound like a Silver Jews album. The self-pitying, self-defeating sound is gone. This is a rock album. It's confident and angry. And when you put it on and you hear Berman sing about smoking the gel off a Fentanyl patch and about how things do indeed get really, really bad, know that he's not talking about losing anymore. Tanglewood Numbers is not just a reminder to his fans that David Berman isn't dead, it's also a reminder to himself.