Photo: Parkwood Entertainment and Disney+

Photo: Parkwood Entertainment and Disney+

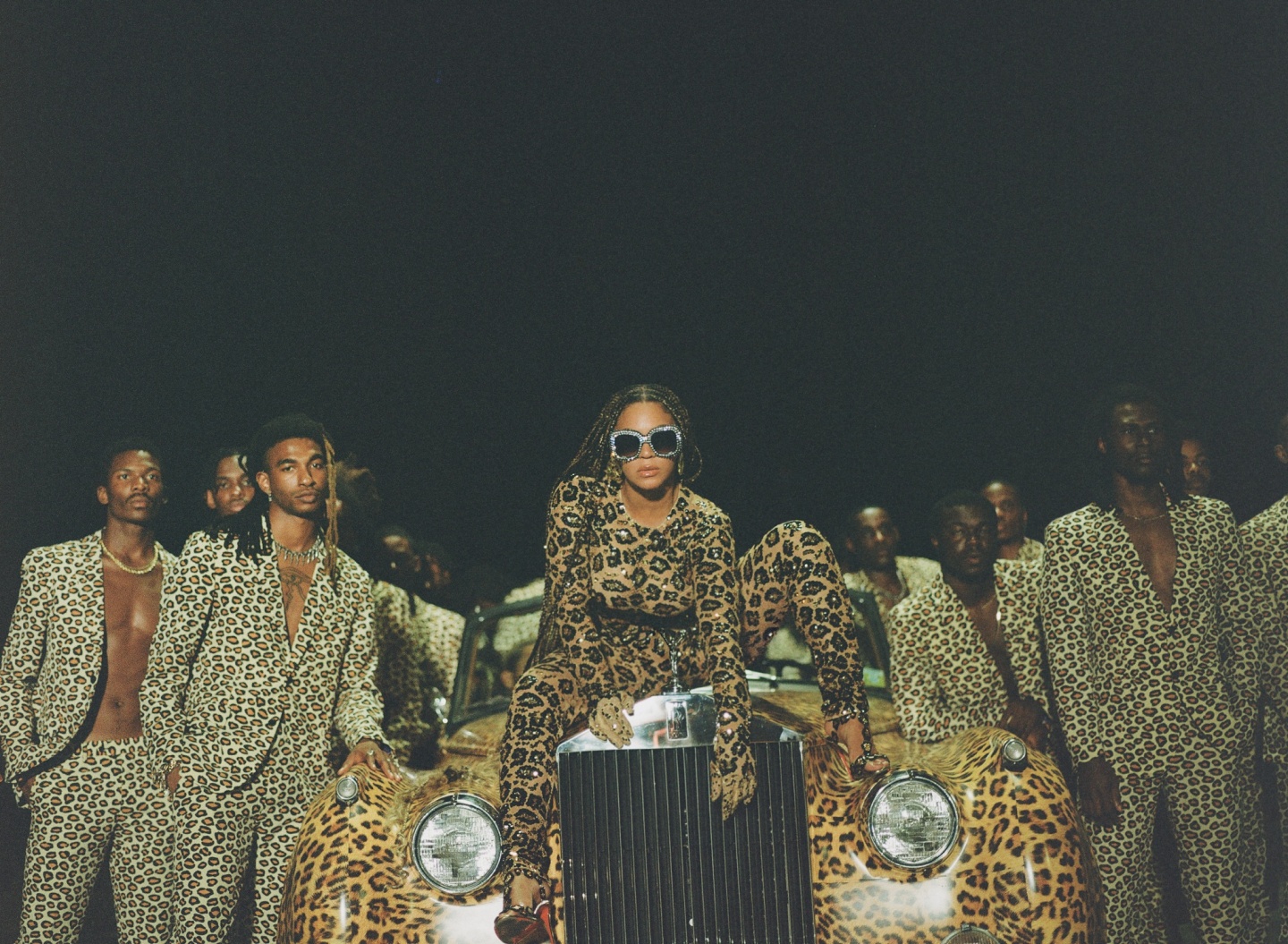

In the two weeks since its release, Beyoncé’s Black Is King has already lived many lives; spotlighting West and Southern Africa through vibrant and meticulously curated wardrobe, set design, and choreography, along with a star-studded cast, that represented a larger narrative about the continent. While the story was meant to loosely mirror The Lion King, spirituality, folklore, and Afrofuturism drove it forward. From Beyoncé’s positioning as an ancestor, the presence of ancient divination, and the tale of a star-crossed return to self, the film was rooted in the past just as much as the future.

“We knew people would be watching who are not culturally proximate to Africa. Even some of us in the diaspora, so we knew it had to be elevated to some form of celestial, cosmological space,” acclaimed director Blitz Bazawule told The FADER, going on to add how elements of Dogon culture, an ethnic group native to Mali and known for having some of the earliest iterations of astrological knowledge, was heavily incorporated into the film. “We did these levitation shots and had no idea what it was going to be like. None of us really knew each other and it felt like we were playing a virtual game of tag. We each just took something and ran with it.”

While everything Beyoncé does drips with intention, the film was originally meant to be a collection of unrelated videos, the first of which was the 2019 single “Spirit.” It wouldn’t be until later in the production process that the pieces of the story would start coming together. “There was so much that was already done,” co-director and Parkwood creative director Kwasi Fordjour told FADER, who noted the shift began after “Find Your Way Back” was shot. “There were so many ideas that we had already been nurturing and just needed the grounding of a story. We were tussling with how the story could progress, and become bigger.”

It wasn’t until Bazawule was added to the project that the film got its narrative legs. “For me, it was like a tapestry. All of these brilliant creations that were created in their own zeitgeists,” Bazawule said. “I came in when a good deal had already been shot, so I could feel the energy.”

Previously, there were plans to shoot additional footage in South Africa, but COVID-19 travel restrictions forced the team to close in on what they already had. It served as an exercise in creating new folklore out of the extenuating circumstances. "When you think about a platform like Disney, I couldn’t always relate to the white prince," said co-director Emmanuel Adjei. "But now it's like we have our own fairy tale that’s going to live on forever and inspire generations after ours."

The FADER sat down with Fordjour, Bazawule, and Adjei, three of the film’s visionary directors, to talk about the importance of prioritizing African creatives in telling African stories and letting the universe make the final edit.

Photo: Parkwood Entertainment and Disney+

Photo: Parkwood Entertainment and Disney+

The FADER: Normally we get Beyoncé's visuals at the same time as the music. What was the thought process behind waiting a year before releasing Black Is King?

Kwasi Fordjour: We weren’t expecting to do a full film! We actually started with a few music videos [for The Lion King: The Gift], the first being “Spirit.” The plan was to do a few additional videos, but as we started to shoot, slowly but surely, as it progressed, Beyoncé wanted to create this as a full film.

How did you keep the momentum of shooting over the course of a year?

Blitz Bazawule: There was so much brilliance that had already happened when I was called in. Almost like an overwhelming amount of beauty. How do you turn all of this into a narrative? I knew for sure we were going to anchor it in the experience of continental Africans, and I knew that I would want to do it in South Africa, among other places. We wanted to juxtapose this rich, regal, rural world with this more urban experience, especially as Simba gets older. That was the main thing: figuring out how to weave that narrative through the music videos that already existed. Some were still being made, so we were able to have everything be in alignment and create a cohesive vehicle. It’s a Beyoncé project, so it was inevitably going to cross worlds, but the question was could we anchor it in a specific place first to come back to.

Emmanuel Adjei: The whole process of building this film felt like creating this painting and every brushstroke adds a new image like you're discovering what you’re making. Sometimes you need to remove stuff, sometimes you need to add a little bit more. Sometimes you have to change your whole palette, but that was an essential part of this project. It was an unorthodox way of making a feature-length project.

Kwasi has mentioned that there were plans to shoot more footage up until the pandemic really set in. Did this inability to travel help you narrow down the narrative?

Kwasi Fordjour: Definitely. We were planning to add more to the story! We had to table that idea and really look at everything we had and go, okay, this is what we've got, here is the messaging, here is the story. How can we enhance this? We had the key ingredients and all of those things helped tell the story the way we told it.

Blitz Bazawule: COVID was such a shift in our entire worldview and I think the universe is so wise. The timing of this piece could not have been better. The fact that we were planning to add more and the universe said nope. We were shooting so much content that we never fully watched or listened to, so we had to go back and create from what we already had.

Photo: Photo: Parkwood Entertainment and Disney+

Photo: Photo: Parkwood Entertainment and Disney+

How important was it to work alongside creatives living and working in different parts of Africa? How did this shape the narrative?

Kwasi: Working with creatives who are living and working on the continent was important because they grounded our ideas with a level of authenticity. It was really important for us to work with directors that allowed their authenticity and passion to lead their creativity. That’s why we went to Blitz, Emmanuel, Joshua Kissi, and Pierre Debusschere because they added to that tapestry we had already started to build. It was important for that to lead the conversation. Beyoncé was very adamant about working with people she connected with, not just personally but with their vision. That’s why so many people watched it and saw themselves in this film; because the directors saw themselves.

Did you learn anything from these creatives that you may not have seen through your own lens?

Blitz Bazawule: I’ve always seen Blackness as a myriad of experiences. I’ve been to Salvador, Bahia, Brazil and if I close my eyes I might feel like I’m in Accra, Ghana. Sometimes you’ll be in Harlem, even, and you might think you’re in Dakar, Senegal. I’ve always seen it as a multiplicity, and this project was a phenomenal opportunity to see Blackness represented with universality. It was so many voices, all singing in a chorus in a way that I’ve never witnessed in my life. As a creator, it’s completely changed how I look at my art, how I look at Blackness in general, and how we communicate with each other globally.

Kwasi Fordjour: All the directors we collaborated with see Blackness differently. They see it beyond the boundaries that are placed on it. That’s the core of it. They all separately grounded it that way.

Emannuel Adjei: What inspired most of the creatives on this project is that it’s not just a personal story, it’s a collective experience. It has become a vehicle to examine and raise a lot of questions about our heritage and about our history, but also about our future. It mirrors the future, it shows what Black people are capable of and redefines the default. It will just create even more beauty and bigger platforms for us to tell different kinds of stories.

This interview has been condensed for content and clarity.