Before 6 7, Skrilla had Kensington. Call it the largest open-air black market on the East Coast; call it the epicenter of Philadelphia’s drug crisis. Skrilla just calls it the block.

More than a backdrop or a backstory, Kensington is the crux of Skrilla’s eerie, off-kilter strain of Philly drill that’s less preoccupied with interpersonal violence than the expensive cars and pharmaceuticals these exploits can provide. His raps — fluid, acrobatic bursts that feel completely unmoored — sit atop beats that sound like the Halo theme or Gregorian chants, resonant and imposing. It is in these soundscapes that his vision of Kensington comes to life: rap music that offers a succinct snapshot of systemic failure.

“The way Kensington is, it looks bad. It is fucked up,” Skrilla says of the derelict Philly neighborhood where he grew up. “But it’s actually people happy with being down there.”

He says he’s met people from all over the states and as far as Paris on its streets, all who have come down to Kensington specifically to “look for dope.” Over the years, he’s come to realize that most are essentially content with their situation. “Nine times out of 10, the people, they're actually happy,” Skrilla sighs. “But all of them need help.”

The way Kensington is, it looks bad [...] Nine times out of 10, the people, they’re actually happy. But all of them need help.

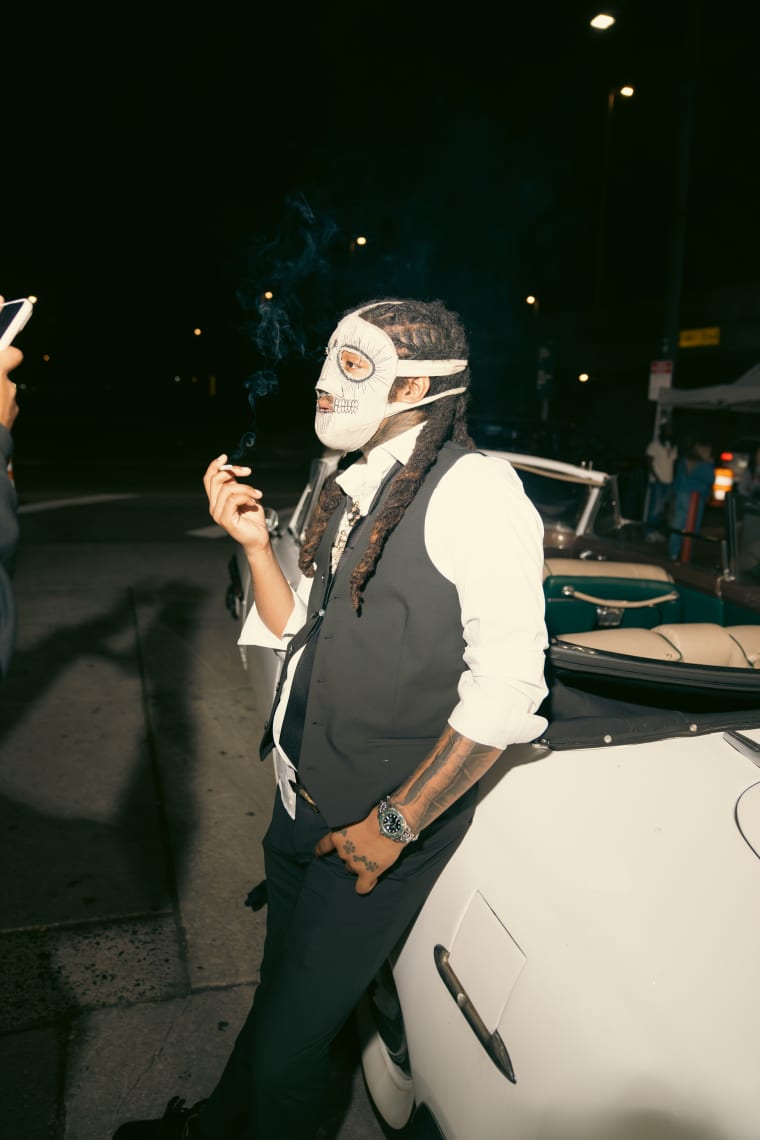

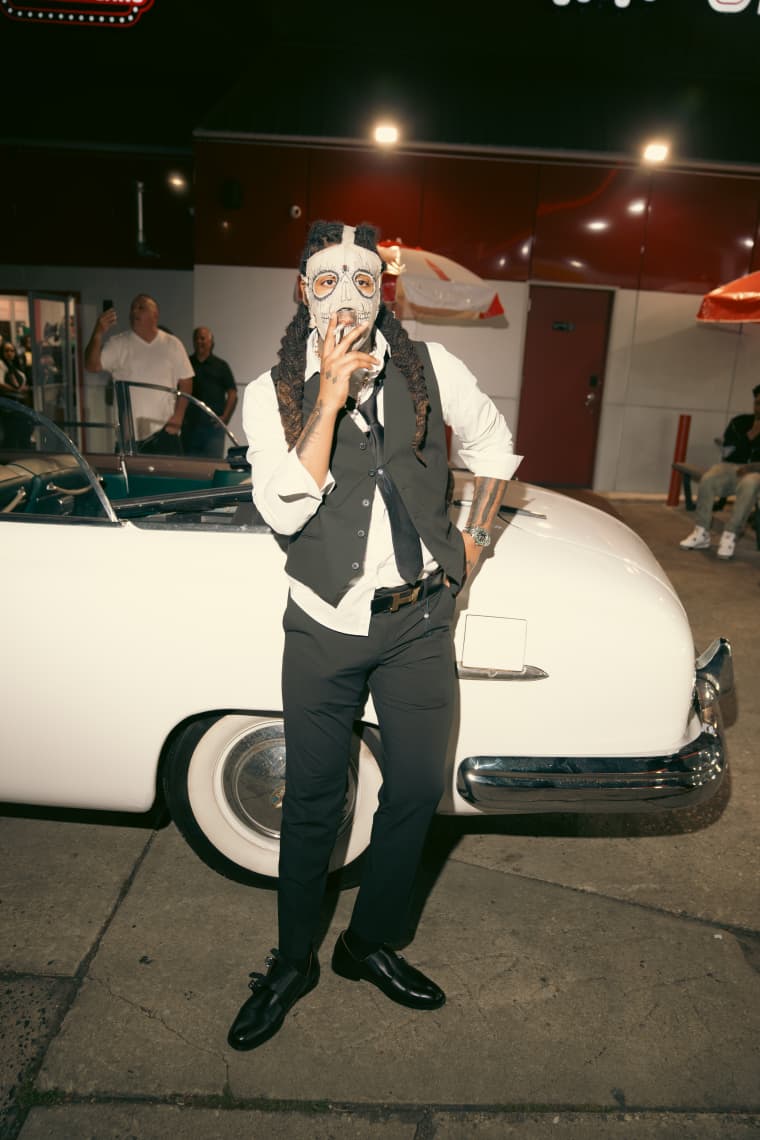

Skrilla, who turned 26 last summer, has been running around Kensington since he was a child. He got pinched for dealing so many times he ended up on house arrest for two and a half years in high school; he has a tiny bone tattoo next to his eye as a symbol for “dog food,” as in heroin, and matching bones and pawprints across the knuckles on his left hand. When he stopped by The FADER office in September for this interview, he was in the process of getting his entire body inked like a trompe l’oeil skeleton ahead of his first U.S. tour.

By then, his runaway hit “Doot Doot (6 7)” had taken on a curious life of its own. What had begun as a bleak, quintessentially Skrilla release last February —“Shooter stay strapped, I don’t need mine / Bro put belt right to they behind / The way that switch brrrt, I know he dyin’ / six, sevennnnn,” he raps — had rapidly evolved into the latest brainrot urtext for Gen Alpha memers.

Blame it on TikTok’s penchant for context collapse retooling any song into a semantic-free soundtrack certainly helped. By spring 2025, hoards of elementary school students were squealing the hook while diabolically flapping their hands. Then, the numbers entered another realm entirely — buoyed by teenage basketball players, Sesame Street, Natasha Bedingfield (her son’s a big fan, apparently), U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer, and, incredibly, my 50-year-old parents at Thanksgiving dinner. “6 7” had traveled far beyond the Kensington streets that started it all.

Skrilla says his brainrot ubiquity is “a dream come true.” (For the record, “6 7” refers to 67th Street in Philly, where Skrilla’s “young bouls” are from; the phrase originated with fellow Philly rapper YSN Uth and trickled up to Skrilla via mutual friend DoodiBabby.) The far-flung notoriety was unprecedented for a song he leaked on Instagram last December with no intentions of actually releasing. And somehow all of this is still just scratching the surface of Skrilla: a man who owns a pet gator (named Tranq, after the city’s drug of choice) and administers Narcan to unresponsive people on the sidewalk, as I watched him do late one night on Instagram.

“A lot of people look at me like ‘Oh, he’s a fucking drug addict. He’s gone, he's done,’” he says. “Then you meet me — I actually got my head on my shoulders, you know?”

Jemille Edwards was born on June 3, 1999, the oldest of four siblings (“I’m a Gemini, two-faced”). His childhood was defined by athletics: “Basketball, track, cross country, football, baseball, everything. My pop made sure we attended school and made sure we played for a lot of different teams,” he says. He was especially good at basketball, playing Amateur Athletic Union up and down the East Coast, but liked cross country best for the extra hours it gave him outside while on house arrest.

Skrilla and his brother Von bounced between their parents, who were separated. In interviews, he’s described his mother as “kinda homeless,” and geographic proximity to Kensington mixed with economic inopportunity offers some explanation for why a 12-year-old Skrilla might’ve started dealing.

It sounds outlandish because it is. And it’s easy to see Skrilla, who, in person, is a consummate performer and a bit of a ham, as a caricature of Kensington’s troubled environment. But both in person and in his music, he can also be disarmingly candid and cognizant of how others see him and his world.

“It’s a bug in my brain sometimes. People meet me, I think about what they think about me while they with me, you know?” he says. “Sometimes I look at somebody’s face expressions and just tell [they see me as an addict by] how they look at me.”

This self-awareness is part of what makes Skrilla’s videography so uncomfortable. My first encounter with Skrilla’s music was through a hanging mic performance of his song “GOD DAMN.” In the video, Skrilla is surrounded by down-on-their luck Kensington residents, all of whom look mildly confused as he dry humps a blonde woman and raps, “When I send that blitz, they gonna get that done / I done popped so many Percs, I fucked a bitch, I couldn't cum.”

At its core, this is trauma porn — Skrilla is pressing a button to get a rise out of viewers, and he presses it because it works. To his critics and casual onlookers, it reads like exploitation regardless of his personal ties to the area or professed affinity for its people. I can’t say I disagree with that assessment. More than a year and a half later, I still find this clip garish and demeaning.

I’m a good mascot for Kensington. I make it look good, I make it look bad, I make it look how it look.

At the same time, dismissing Skrilla’s appeal as purely exploitative misses the mark. Instead, his refusal to separate the drug-slinging tropes of trap music from its real-life consequences feels mildly radical, if not quite political. In Kensington, drug arrests are up and shootings are down, but critics say the city hasn’t really fixed the problem, just shifted it somewhere else. This will be a familiar, bipartisan story to Americans no matter where they’re from: Donald Trump’s National Park Service has “cleaned up” D.C. in much the same way Gavin Newsom’s statewide policies approach homeless encampments in California.

As clumsy and off-putting as Skrilla’s representation may be, it offers honesty if not quite dignity. I’ll take that over the politically correct lip service practiced by local lawmakers who turn around and vote to restrict and reduce mobile outreach in the area.

“I feel like I’m a good mascot for Kensington,” Skrilla says. “I make it look good, I make it look bad, I make it look how it look.”

Haze OnTheCam

Haze OnTheCam

Haze OnTheCam

Haze OnTheCam

Skrilla says he’s more sober now than he was in the past, and approaching the recording process of his upcoming album, Z, set for a Q1 release via Capitol Records, with greater discipline and intent. Throughout our interview, I get the sense that Skrilla sees more of himself in the average Kensington resident, and more of Kensington in the world than we care to admit.

The demos for his upcoming album include a track called “2 3,” which clearly follows “Doot Doot” without feeling totally derivative, and a magnetic dirge tentatively titled “Skrilla Swish,” wherein Skrilla bemoans the scrutiny of fame. “Why the fuck I can’t hop out the whip and just start window wiping?” he wonders rhetorically. Z is set to include previously released singles “Bhrome Heart” and “Rich Sinners” with Lil Yachty, and showcase a handful of interludes recorded by Kensington residents.

During our interview in September, he’d mentioned potential features from Rob49 affiliate Moskino and fellow Philadelphia oddball Tierra Whack (He went to school with her family; “That’s my baby — we lowkey married forreal”). When we caught up again in December, Skrilla said he still wasn’t sure who’d wind up on the record and that he had just been in the studio the previous night with Brazilian rapper TZ da Coronel, who he’d met on tour in São Paulo: “The favellos [sic] are just like Kensington but bigger.”

The most surprising thing about Skrilla is how exceedingly normal he is in person. Though he’ll drop a casual “6 7” in conversation, and instantly repost just about anyone using the meme on social media, he seems genuinely unphased by the song’s larger-than-life success, happy to capitalize off his moment but by no means pressed to extend it. Next to the desperation of attempted viral sensations like Jimmy Fallon and Sydney Sweeney, he comes across as downright wholesome.

Skrilla’s music is maturing alongside him, if only by increments. He started rapping in 2018 when his first child was born; now a father to two daughters, with two babies on the way, life has settled into less chaotic rhythms. When I ask what’s changed in his music, he offers a Proustian memory.

“You know how you could smell something that your grandma used to cook back in the day and you get flashbacks in your head? When I listen to my old shit, I get flashbacks to what I was doing during that time,” he tells me. “A lot of the time I’m trying to write now, I’m not actually out here running around, shooting at nobody right now. I'm not selling drugs at every corner, I'm not sitting on the block middle finger to the cops every day. So it's a different type of vibe from my music back then.”

He continues, “I still do the shit that I used to do, but not like … I was drunk, bro. I'm chilling a little bit now, you know? Like, we in New York – back then I wouldn't even came out here. I'd have been around the block right now just sitting there, hanging with junkies, trapping. I'm doing a whole different type of thing now.”

Haze OnTheCam

Haze OnTheCam

Haze OnTheCam

Haze OnTheCam