Prior to the release of his latest album Smokey Rolls Down Thunder Canyon, FADER E-I-C Alex Wagner journeyed to Devendra Banhart's mountain home and talked to him about literally everything (including pigs).

STORY Alex Wagner PHOTOGRAPHY Tierney Gearon

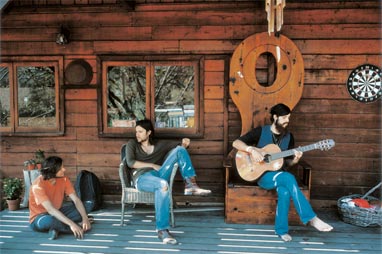

After several miles of car commercial twists and turns through the lush wilderness of Topanga Canyon—former home to Neil Young, Joni Mitchell and the Manson Family—a sharp turn to the left leads up to the woodland hideaway that Devendra Banhart has called home for the last eight months. On this particular day, the typically cloudy westside skies had turned a clear blue and the canyon’s surrounding mountains were a preternatural shade of green. The musician Noah Georgeson, a frequent collaborator of Banhart’s, was upstairs mixing the songs for Banhart’s upcoming album in a room that was surrounded by broad picture windows. “I mean look at it,” he said, gesturing towards the view. “We could be anywhere—we could be in South America.”

The front door of the house usually remains unlocked and for the last few hours there had been a scrap of paper taped to the front door. In block letters, someone named Nathan explained enthusiastically that he’d gone camping in Big Sur with a girl he’d met in town. Several days prior, Nathan had come up to Banhart at the local coffee shop, informing him that he’d hitchhiked his way to California in the hopes of playing him a song—he then pulled out a thumb piano, played the song and was invited to come up to record on a handful of tracks for the album. In the meantime, Nathan had been staying at the house.

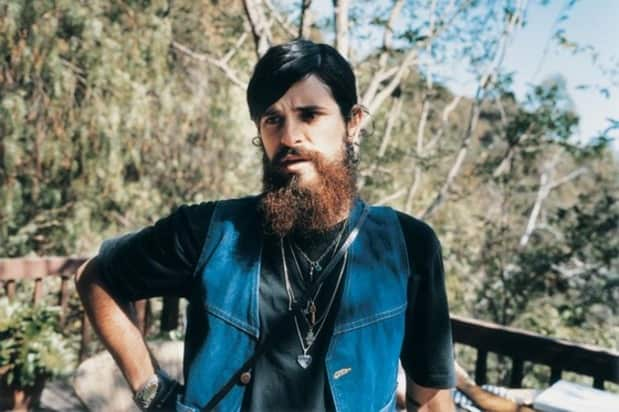

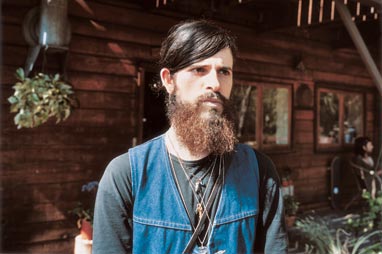

Banhart was running late and so Georgeson and Luckey Remington, an artist and another Banhart collaborator, gave a quick mini-tour of the house: a beaten-up crimson velvet couch and flattened mustard-colored chair in the living room that once belonged to Jim Morrison, piles of vintage shoes—Chelsea boots, cowboy boots, espadrilles and huaraches—that mostly belonged to Banhart. Fifteen minutes later, a dusty Mercedes Benz with rainbow decals on the windows pulled into the makeshift driveway. Banhart walked through the door, shirtless and wearing a shrunken, dark denim vest, denim flares and buckled sandals. His long hair was pulled into a ponytail and his brown beard had grown full enough to betray coppery strands at its tip. Banhart apologized for being late, cracked open several fresh pineapple-coconut waters, pulled out a bottle of Pampero Reserve Venezuelan rum for makeshift piña coladas and sat down on the front porch to light one of Remington’s stallion-black clove cigarettes.

Devendra Banhart first registered on the musical radar five years ago with his eerie, lilting, weird home recording Oh Me Oh My, which was released by NYC-based indie Young God Records. In making the album, Banhart was frequently on the road and would call Georgeson’s answering machine to sing a few bars into the phone whenever the muse struck him, beginning his messages with, “Don’t erase this!” Whispery innocence and the wide-eyed enthusiasm of an artist at once in love with the world yet still searching for a community—imagined or real—to call his own were hallmarks of Banhart’s early recordings.

They sounded naïve but pleasant enough and would likely have been otherwise forgotten were it not for the complexity and poetry of Banhart’s lyrics (Oh Me Oh My had love songs about Michigan State and borrowing someone’s teeth to see in the dark) and the uncanny impression that this was someone whose best work lay ahead of him. There were flourishes of flamenco guitar, threads of spirituals and surf rock that couldn’t be chocked off as just more plaintive, self-aggrandizing post-millennial bedroom musings. And there was also Banhart himself, a striking, sexualized sylph who seemed to roam wilderness and city alike, making friends and spit-swapping songs with Northern California folk heroes like Joanna Newsom and Andy Cabic of Vetiver—it was a king-making moment when Banhart emerged with his motley band of troubadours, ones who somehow managed to rekindle the dusty notions of love, faith and peace. It was the beginning of something pure and strange, and to quite a few people, very beautiful.

Until the age of 13, Banhart lived in Caracas, Venezuela (his mother is Venezuelan) and the political chaos of that time made its mark. “Chavez kicked [my dad] out and confiscated his computers—said he was CIA,” says Banhart. “The paranoia led to some really, really ridiculous shit. One American who has two computers, must be CIA!” His father was the one who began Banhart’s musical education at a young age, playing him Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and cultivating an interest in sound systems alien to their native Houston, Texas. His parents also introduced him to the great religious texts, including the Bhagavad Gita and the writings of Rumi, in the hopes of indoctrinating their son to the spiritual teachings of figures from across the spectrum of faith. It’s a good bet that Banhart’s wild mountain spiritualism has as much to do with transcendental meditation as it does Neil Young.

Banhart’s first substantive release, Cripple Crow, was released in 2005 by indie powerhouse XL Recordings and featured, among other things, songs about having Chinese children, a slow waltz-doo wop about a hermaphrodite’s love for little boys and a chattering, clattering spoken-word sign off in Spanish that was essentially an imaginary conversation with the actor Gael Garcia Bernal (whom Banhart had never met). “I just start talking in what I call the chichero voice,” says Banhart. “Chicha is this sweet drink with cinnamon, and the chicheros drive by the town and they’re just going, ‘Chicha! Chicha!’ In this voice! And in my head I was like, I’m just gonna talk to Gael.” Banhart would later meet and record a song with Garcia Bernal for the final scene in the latter’s upcoming film, Défecit—it also appears on Banhart’s upcoming album, which at press time was being called Jewish Anarchy, but will probably (definitely) be renamed.

The organizing principles of love and peacefulness, patchouli and righteousness—’70s bedrocks that have always made Banhart a target for calls of derivative revivalism—are still with him and perhaps even more convincingly so now that he’s living with Jim Morrison’s old loveseat and being represented by Joni Mitchell’s legendary manager, Elliot Roberts. “He came to the worst show I ever played,” says Banhart, someone put roofies in my beer. I passed out in the Port-a-Potty and they wheeled me through the crowd in a golf cart. [The whole time] I was yelling, ‘Orphan legs! Orphan legs!’”

“He came to the worst show I ever played,” says Banhart, someone put roofies in my beer. I passed out in the Port-a-Potty and they wheeled me through the crowd in a golf cart. [The whole time] I was yelling, ‘Orphan legs! Orphan legs!’” -Banhart

Banhart’s camp—from his collaborators to his publicist—comes from the celestine road less traveled. His publicist, Howard Wuelfing, is someone Banhart refers to for matters of “the occult, gnostic, unorthodox, magical—everything. From Aleister Crowley to the I Ching to Freemasons and Rosicrucians to the Kabbalah to pagan and wicca. He’s well versed in the goetia—which is the demonology—and white magic, of course.”

The alchemy of these latest influences and personages has created a vein of cosmicism and magic in Banhart’s newest work: a deep purple door in the sonic sky that opens unto a parallel universe populated with tarot mystics in the mold of Alejandro Jodorowsky, where snatches of Mel Torméian croons about circumcision rites waft through outer space. Jewish Anarchy—or whatever it’s called—builds on the psychedelica of Cripple Crow but takes Banhart’s songs to deeper, moodier corners, the travel diary of an artist who has traveled around both the world and his own druggy mindgarden to gather a bouquet of fragrant, poisonous daisies.

“Yopo,” a track on the new album, gets its name from an experience in Brazil when Banhart & Company decided to take an unguided tour around the Tierra Azul—a mountain-sized stone covered in blue moss, and a powerful energy spot according to local lore. “We realized we were lost in the fucking jungle and we saw a stork land,” recounts Banhart, “So we followed it and it led us to a Yamomami camp—they’re the Indians who live on the border of Venezuela and Brazil—and they were doing yopo. It’s a red powder that you blow through a long tube, one in each nostril. And we did it and on the first nostril was like the worst pain—your head getting crushed in. “Next nostril, suddenly you break through into a world of ultravivid hyper-dimensional clarity, like slick, almost MTV music video worlds. Everything is the other side of pure clarity. Your eyes are clean and suddenly this lavender has these sparkles and they look like little trails of laughter. And it was amazing. But it wasn’t a strong enough dose.”

“Seahorse,” an extended jam on the new album, has the lurid, dark sexuality of the Doors, while on other tracks, Banhart’s voice sheds its feminine vibrato and adopts a velveteen croon—aided in no small part by his rental of Frank Sinatra’s reverb from a westside church. There are other tracks that channel disco and funk, there are classic ballads and there are more than a handful of songs in Spanish. (Banhart is planning to release an all-Spanish compilation and tour Latin America and Spain sometime later this year.) Besides Georgeson and Remington, the album will also feature the Strokes’ Nick Valensi singing I bribed the whore of Babylon to lend me her waterbed in French and Chris Robinson of the Black Crowes playing the charango. “It’s an Argentinian Chilean Peruvian indigenous instrument,” says Banhart. “I think it has 12 strings, like a mandolin, and it’s made out of an armadillo shell.”

In between sips of piña colada on the deck, Banhart continued to silence his ringing red Motorola RAZR and showed me a broken toenail he got from running around the night before, though he wasn’t exactly sure how. We went upstairs to hear some of the latest mixes for the track tentatively titled “Shoobop Shalom” and then Banhart brought me to the studio room where he works on his art (he has shown at galleries on both coasts)—on one wall, small, dried seahorses were hanging from nails. In a nearby bedroom, Banhart pulled out a pristine red velvet suit he recently purchased that once belonged to Mick Jagger, and then took me to the bookshelf to see if were are any books by Dee Brown, one of Banhart’s favorite writers and author of Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.

Back downstairs on the deck, chipmunks were running around and Banhart explained that he’s trying to adopt 12 potbellied pigs from a nearby neighbor. “That’s like opportunity!” he announces. “I had to take that opportunity!” -Banhart

Back downstairs on the deck, chipmunks were running around and Banhart explained that he’s trying to adopt 12 potbellied pigs from a nearby neighbor. “That’s like opportunity!” he announces. “I had to take that opportunity!” When Banhart finally returned to the sitting position, he explained the difficulty he’s had making music videos. Previous stabs were derailed—and sometimes complete failures—due to miscommunication and a lack of funding. The song “Heard Somebody Say” off Cripple Crow was intended to have a fruit goddess and a pyramid of bananas, with Antony (of Antony & the Johnsons) as a glowing oracle with “black orchids coming out of his face” according to Banhart. Most of this, he said, was supposed to be executed through CGI, but the budget ran out.

Banhart explained that the video for the album’s other single “I Feel Like a Child,” had similarly ambitious plans: “The idea was to have a dark screen, just us playing the song, but then the camera was gonna go in my mouth, and there would be a whole universe in there,” he said. “And I’ve always had this image of a pink dolphin with the head of [Young God founder] Michael Gira. I stand by a river and my beard grows over to the other side of the river, like a rainbow, and then this dolphin starts jumping over it in a loop.” None of these elements ended up in the final cut for either video, and what was released instead were two odd, amateurish pieces that seemed to be missing their explanations. There are, as yet, no video treatments for the next album, and it’s unclear whether XL Recordings will ever have enough budget for the CGI and sound stages and costumes that will presumably be required for the videos to accompany an album as absurd and exotic as Jewish Anarchy. But until then, Banhart remains 1400 feet above sea level with the ghosts of the ’70s, mediating on Khalil Gibran’s Lebanese poetry and Victor Parra’s Afro Cuban jazz. And the view from all the way up there is starry and vast.

Devendra on the high school experience that changed his musical life:

Devendra on the inspiration for "Tonada Yanomaminista" (hint: drugs):

Devendra on magically meeting Gael García Bernal:

Devendra on mean New York and nice California:

The making of Smokey Rolls Down Thunder Canyon

"Tonada Yanomaminista"

"Rosa"

"At the Hop"

"I Feel Just Like a Child"