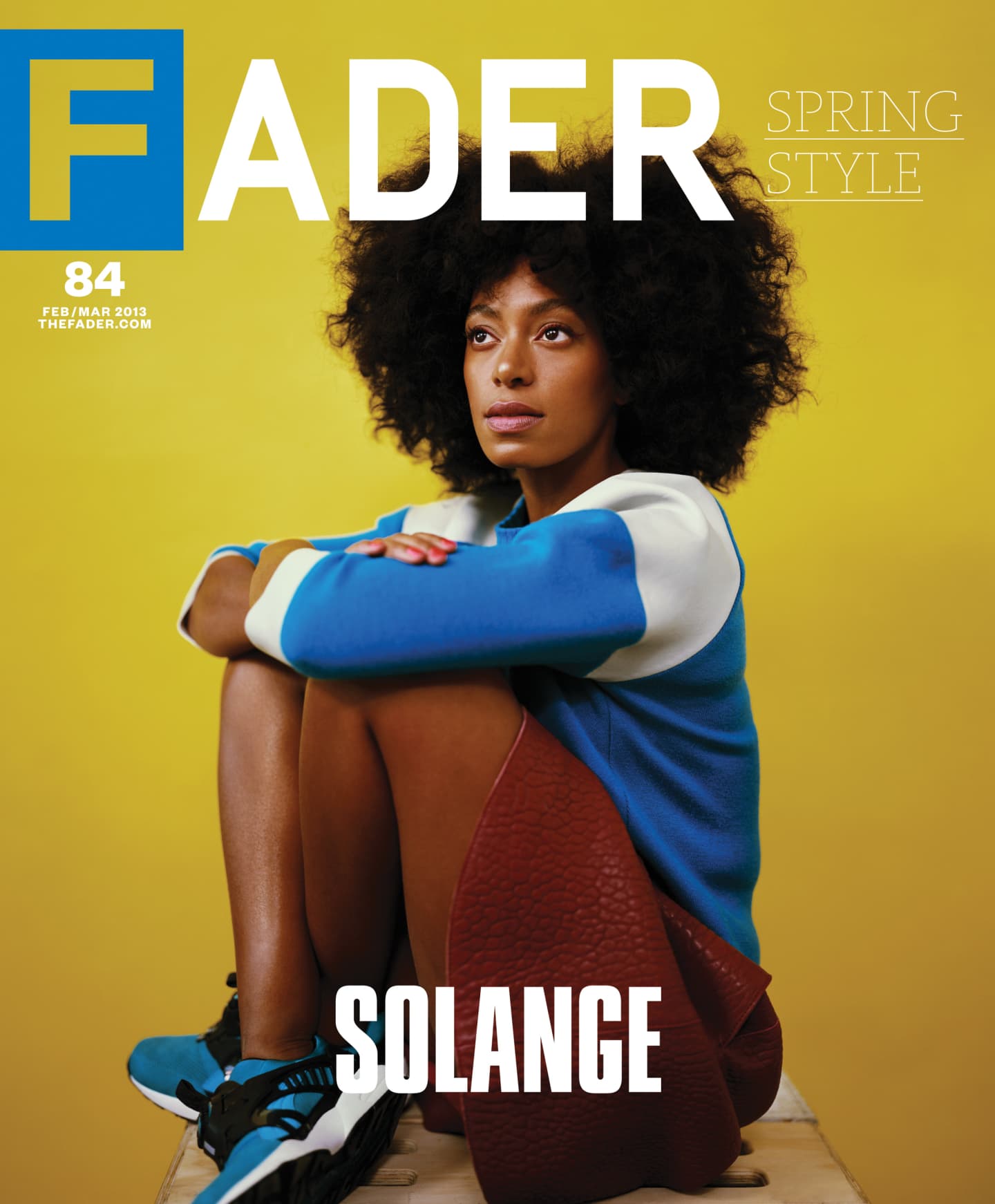

Solange: Rise and Shine

Ten years after releasing her first album, Solange is poised for a new dawn in her career.

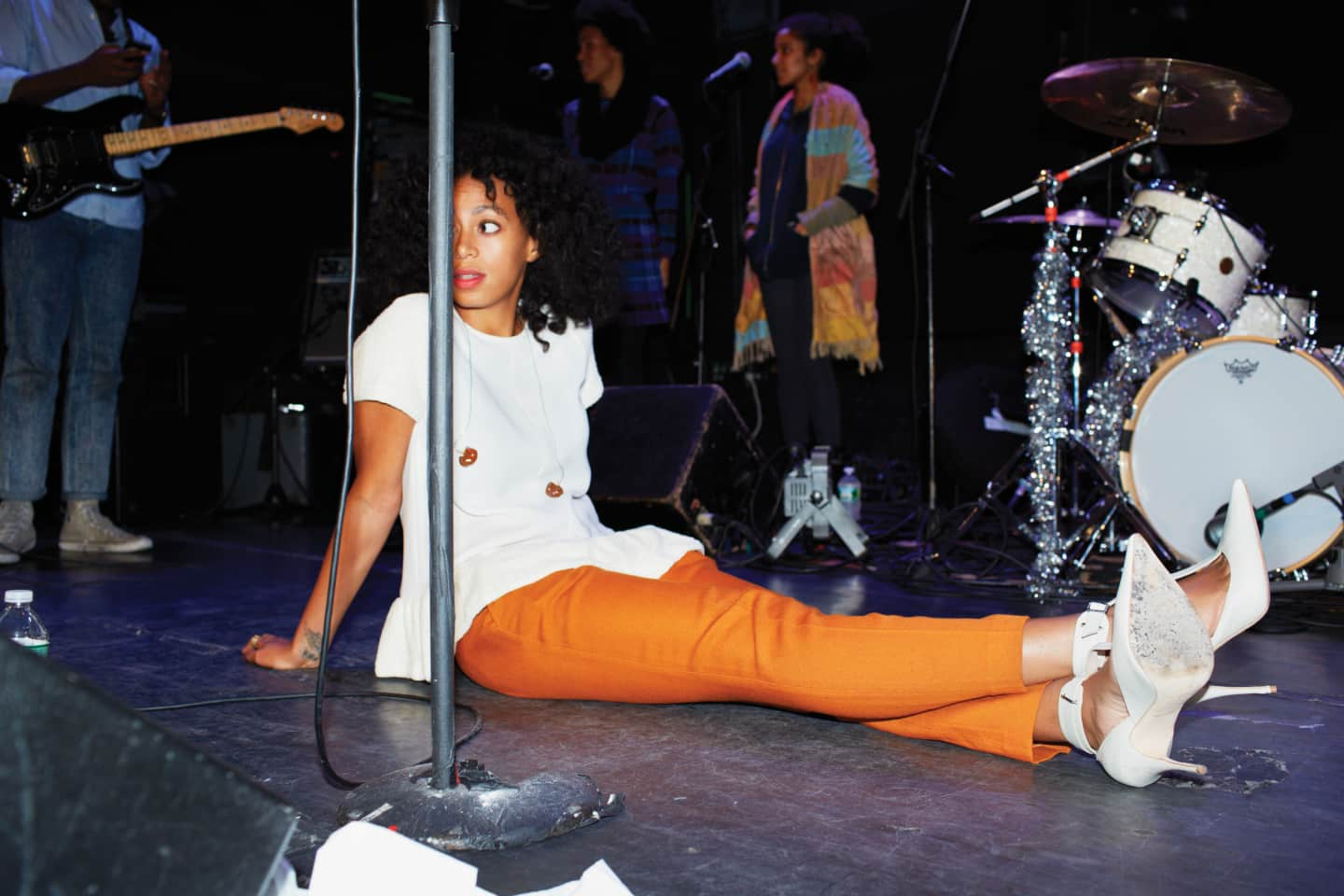

There is a heavenly light in New York’s Bowery Ballroom at two in the afternoon. Being that it’s a nighttime place, few would know it, but the sun just pours in all day long through a wide, arched, south-facing window. It’s at this bright, odd hour that Solange Knowles, as sunny and ethereal as her name would suggest, arrives to rehearse for her second performance in a sold-out run of shows this past December. Dressed smartly in a flounced tunic, a pair of pumpkin-colored trousers and T-strap heels, she looks as if she could just as easily be heading to a job interview, and her hair, the only unruly detail in this otherwise business-chic look, forms a broad, hazy black halo around her delicate features.

It’s for the untamed elements in Solange’s personal style—that, and the fact that she deigns to pal around with the Brooklyn bohemia—that the media often pegs her as the “free-spirited” (or more damning, “hipster”) younger sister to the astronomically famous Beyoncé. The simple exercise of compare and contrast that’s typical to any set of siblings is extrapolated and hyperbolized, or, as Solange succinctly puts it in her leaked, 2008 single, “Fuck the Industry (Signed Sincerely),” I will never be picture perfect Beyoncé...but everything I’m not makes me everything I am. The tabloids are just another place she happens to find herself, no thanks to her god-given name, but something in her focus before the show tells you that the place she most desperately wants to be judged is here, onstage.

Solange pulled together her current live band with the help of Dev Hynes, her guitarist and co-writer/producer on 2012’s True EP, who also makes records under the alias Blood Orange. Though the group has only been rehearsing collectively for about a month, they function like a well-oiled machine, casually half-stepping the choreography as they run through a near-identical set to the one they performed last week at Bowery: each of the seven songs off True, plus two cuts off her 2008 album, Sol-Angel and the Hadley St. Dreams. Solange makes little adjustments to almost everything, recalibrating the levels in her earpiece—“Did something shift in the middle? Sounded like all the subs went out and I was trippin’”—and grilling the lighting guy on his cues. “Just remember, on that last hook, to slowly bring up the lights.” She even jumps offstage to hear the sound from the house floor, arms crossed at her chest, gaze fixed, foot tapping.

Everything seems to be going smoothly until a laptop crashes, and the uh-ooh-oh-oh’s on the backing track to “Locked In Closets” are coming in a beat too soon and throwing everyone off. The onus is on percussion, and Patrick Wimberly, Solange’s tour drummer and one half of the Brooklyn band Chairlift, hustles to reprogram the audio. They run through the song several times, the glitch appearing and disappearing at random, before going into full-on damage control: a home computer is fetched, the Apple geniuses are summoned and Solange takes a seat on the floor, trying not to panic. The kink is eventually worked out, and everyone says a small prayer for the software before setting about learning “Cosmic Journey,” an airy ballad off Sol-Angel that Solange would like to play to bulk up the set. Here, she goes into full-on coach mode, drilling the harmonies, percussion and melody, but everyone is unnerved from the first hiccup, and seems to struggle to get their parts correct. Meanwhile, members of the opening band, Sinkane, who are well past due to take the stage for their own soundcheck, have collected in a pool of instruments and nerves, waiting while Solange asks her band to take it one more time, from the top.

Like the Beyoncé creation myth that’s been drilled into our collective consciousness by countless music television mini-docs and Oprah-Ellen in-depths, Solange’s childhood story also played out on the stage, albeit a smaller one. Her earliest songwriting accolades came in the form of a United Way songwriting competition, for which she won first place out of a pool of 20,000 young applicants when she was in the fourth grade. She studied ballet and danced competitively from the age of three, and, at 13, began doing it professionally for her sister’s group, Destiny’s Child, when one of the backup dancers got pregnant. Since school was becoming “a bit of a nightmare” for Solange (“I was having a tough time—either kids [were] being like super rude, like, ‘you think you’re all that,’ or being like, ‘can I get tickets?’” she says), and since her parents were already struggling to balance being with Beyoncé on tour and being home with Solange in Houston, they agreed to let her get a private tutor and dance for Destiny’s Child on the road. “It was really nice, ’cause in a weird way, we were able to have a lot more of a consistent family life,” she says.

Being on tour wasn’t all curtain-call roses for Solange, though, especially when she suffered a major knee injury that took her out of the game completely. “I had to be in a brace, and it was like my whole world—especially as a teenager—[was] over,” she says. By that time, Solange only had two more years until she would’ve completed high school, and her parents saw no reason to send her home, so she stayed on the road with the tutor. It was during this period of convalescence that Solange discovered the balm of self-expression and got serious about her songwriting. The fruits of those early efforts ended up as two tracks on Destiny’s Child member Kelly Rowland’s first solo LP, Simply Deep. “Kelly, I can’t believe she had a leap of faith in me at 15—I had just turned 15!” Solange says, almost surprising herself with the precocious timeline. She started shopping around her other material, including the single “Feeling You,” and was soon signed to Columbia for her first record deal.

In 2002, Solange made an early promotional appearance on BET’s 106 & Park to premiere her “new joint” “Feeling You,” joined by Jay-Z, who was supporting his recently released double album, Blueprint 2, and her sister (Jay’s then girlfriend, now wife). Wearing a slouchy cap, gypsy skirt and tassled boots, her hair long and crimped, the 16-year-old Solange seemed, even then, to be allergic to nepotistic handouts. Despite her sister’s genuine endorsement— “She’s very talented…I can’t wait for the world to see her”—it’s as if Solange already knew the only way she’d survive is if the music spoke for itself. Onscreen, she wastes no time explaining that she wrote, co-produced and developed the treatment for the song and its Rasta-themed music video, and when the interviewer asks her if she feels any pressure being Beyoncé’s sister, she’s measured but terse. “Well, actually, it’s a whole different sound...She’s a beautiful person to be compared to, but hopefully, once the music comes out, I’ll make a name for myself.” A few months later, Solange released her debut, Solo Star, a titular declaration of independence that, for a 16-year-old, feels appropriately 16, like the major label record version of playing house, and continued on the road for another grueling promotional cycle.

“I was opening up for Justin Timberlake, which was a huge opportunity for me, and I was just like, I want to be at home with my boyfriend!” she says, explaining that they’d been together on-and-off since she was 13. “I was only on my third show, and I kept getting strep throat. I was so relieved that the doctor came and he was like, You can’t sing. I was like, Fuck yes.” During that year-long hiatus, Solange followed her domestic instincts, got hitched to her now ex-husband, Daniel Smith, gave birth to her son, Daniel “Julez” J. Smith, and moved to Moscow, Idaho, where Smith had been finishing up college. “A lot of me wanting to get married so young and have a kid and move to Idaho and the country had to do with me, [from age] 13 to 17, being on the road and having to work so much,” she says. It was during this time that Solange also made a few misguided ventures into acting, appearing in movies like Bring It On: All or Nothing, the direct-to-DVD third installment of the popular Bring It On franchise—nadirs in her career that, in turn, would spur her to rethink her path so as to not become mere marginalia for an US Weekly slideshow on “Stars Who Wed Too Young.” “It wasn’t really until after Julez was born [in 2004], that I started writing again,” she says. “But I was writing these ’60s soul and pop records and no one was picking them up. That’s kind of what transitioned me into doing [the Sol-Angel] record, because I just kept writing them and nothing was happening, and I was like, Well, I guess I can give it another go.”

Sol-Angel, the album she eventually released on Interscope/Geffen, is largely a collection of the records nobody else wanted, and unluckily predates by a few years the retro sound Adele would tout to Billboard glory. The opening track, “God Given Name,” deals explicitly with Solange’s struggle to find her footing in an industry to which she’s seemingly been granted golden access. Over instrumentals that land somewhere between ’60s R&B and trip-hop, she sings, I’m not becoming expectations/ I’m not her and never will be/ Two girls going in different directions/ Traveling towards the same galaxy/ Let my starlight shine on its own/ No, I’m no sister/ I’m just my god given name. For an audience accustomed to Beyoncé’s public polish, Solange’s lyrics might read as provocation, but really, for her to deny there’s any existential conflict would be much weirder. Even if Beyoncé is the proverbial albatross around Solange’s neck—a good omen or potentially a curse on her journey toward pop stardom—Solange is still innately blessed, and talent is the family business.

In this way, it’s nearly impossible not to draw a corollary, as Dev Hynes does, between the Knowleses and the two most famous Jacksons, Janet and Michael. Both the elder siblings have had outsized careers as pop royalty and are notorious perfectionists, inclined to showmanship unparalleled by most mortals. The two younger siblings, gifted in their own right, are saddled with an unfair “advantage” that only seems to breed incredulity and a hard eye to their successes and failures. While Michael and Beyoncé B-sides are simply single flares in a never-ending pyrotechnic finale, Janet’s and Solange’s lesser tracks are snuffed out from the start.

“I feel like I’ve spoken about Michael Jackson too much,” says Hynes, when we meet a few weeks after the Bowery show to talk over coffee and a banana at his local East Village Starbucks. ”That’s just me every day, I guess, but I really see the parallel. [Solange] is now on her own. People view her separately. In the exact same way, I’m sure people didn’t really want to give Janet a chance—I think this is her Control moment.” Hynes is, of course, referring to Jackson’s third studio album and not a state of being (though it was that, too), which she made with Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, the acclaimed production duo and one-time bandmates to Prince. Arguably the most cohesive album Jackson has ever made, Control birthed a collaborative relationship with Jam and Lewis that would see her through her golden quadrumvirate of releases, janet, Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814 and The Velvet Rope. It’s too soon to say that Hynes might be Solange’s Jam and Lewis (and potentially apocryphal, seeing that, at the time of writing this article, Q-Tip had been in talks to produce Solange’s forthcoming full-length), but he’s most certainly a champion of the Minneapolis Sound the duo made pop gold in the ’80s and ’90s. With its mix of funk, soul and New Wave flourishes, the Jam and Lewis vibe Hynes favors was a fruitful vein to follow after Sol-Angel—the big-band brass replaced by synth, the bombastic percussion digitized and blown out. “I intentionally didn’t listen to [Sol-Angel] before because I didn’t want anything to taint me,” says Hynes. “Now that I’ve been able to listen to it, it’s pretty next-level. It’s actually way more experimental than anything on True, I think.”

Just a year after Sol-Angel was released, Solange began actively trying to get out of her contract with Interscope, with whom she’d become increasingly unhappy. “I’d made it pretty clear what I wanted to do, and how I wanted to roll the record out,” she says. “I didn’t agree with them that certain stipulations would ensure that people were gonna go out and by the record. It was so institutionalized towards the end that I just couldn’t imagine actually making a record with those things, that noise again.” Judging by the success Solange has had marketing herself and her finesse in rolling out True, it seems she’s right to want to avoid the system. “I have just three questions that come into my mind when I get an opportunity,” she says. “Will this help me, will this hurt me, or will this just [make me] stay the same and not progress?"

During this time, Solange was becoming increasingly drawn to New York’s independent, creative fringe, and literally joined it in 2011, when she relocated to Brooklyn and moved in with her boyfriend of four years, the director Alan Ferguson. A top floor walk-through in the now gentrified Italian enclave of Carroll Gardens, Solange and Ferguson’s home is casually tasteful, with modern, geometric throw rugs and mid-century side chairs. A Phyllis Galembo monograph is stacked on top of a pile of art books on the coffee table and there is a largish television (on which Solange tells me she stayed up too late the night before our interview, watching The Real Housewives of Atlanta). Solange chose the neighborhood for its proximity to the French-English school Julez attends around the corner. It’s in quotidian details like this—the scheduling of an interview around school hours, the wrangling of a babysitter for the evening of her Bowery performance—that make you realize that if any member of Solange’s immediate family should be credited for enabling her to enter the second half of her 20s as an uncompromisingly grounded, focused woman, it would very likely be her son. “In all aspects of my career, simplicity is so key,” she says. “I think it has a lot to do with how much the quality of my life has improved since Julez started school, which pretty much implemented a schedule and a lifestyle that revolves around a nine-to-five hour,” she says.

In 2009, Pitchfork noted her turn toward the alternative in their premiere of her cover of Dirty Projector’s “Stillness is the Move,” which ingeniously swaps David Longstreth’s peripatetic guitar line for the similarly syncopated, high-fretted and oft-quoted one from Soulmann & The Brother’s “Bumpy’s Lament.” The track was later pulled from the site at Interscope’s behest, but the write-up still serves as an early testament to Solange’s transformation, citing a Boards of Canada sample and the now-infamous time she brought Beyoncé and Jay-Z to see Grizzly Bear play an outdoor show in Williamsburg. But what could be perceived as a calculated play for indie cred on Solange’s part can also just as easily be chalked up to the fact that she actually was becoming independent, and more importantly, growing up. “[Sol-Angel] was put out almost five years ago,” she says. “[In] four years, there’s been so much artistic growth, so much growth just as a woman in [my] 20s, but especially as an artist. You’re exposed to so much more from age 21 to 26, and you sure as hell care a lot less. It’s been a little weird, for me, getting feedback—the last album was so different than this one. I am like, Yeah, I was 20 when I started writing it. Is that supposed to be shocking? If it sounded similar, that would be really strange.”

Still, there’s no denying that Solange’s preference for the fresh kids, the what comes next kids/ The see you at the art exhibit, oh, hell yes kids, as she describes them in “Fuck the Industry,” means that she is often in the position of being the gigantic fish in a little pond, and, in that sense, never just a fan—always an ambassador. Her ability to bring up the artists around her is obvious—both in Hynes’ heightened demand as a songwriter and producer, and the fact that by putting out True on her friends Ethan Silverman and Chris Taylor’s Terrible Records, Solange has given the venture the most exposure it’s received to date, despite the fact that Taylor’s band Grizzly Bear is already pretty big in its own right. It’s this tension between independent and mainstream success that can sometimes make it feel like Solange is an invasive species in a delicate ecosystem—a dazzling bloom that could potentially choke out the native roots of a DIY scene if left unchecked. In other words, if you see a songwriting credit on an upcoming Beyoncé record attributed to Chairlift’s singer, Caroline Polacheck (per an overheard conversation during rehearsal), don’t be surprised. For Solange, it’s just giving her friends a shine, but those lights can be overwhelmingly stadium-sized and blinding. When you see Grizzly Bear endure a FUSE TV interview filmed before their sold-out Radio City Music Hall that revolves almost exclusively around Beyoncé and Jay-Z being fans of its music—a coup in its own right—you get an inkling of what it might be like for Solange to have to distinguish herself from her sister. It may be why she’s been so careful and slow, by current music industry standards, to release her albums. Finding your own space in the music industry proves difficult when your sister inhabits every corner.

Solange had been actively searching for the sound of her third record before she actually met Hynes, when they were both called in to work on a track for their mutual friend, the rapper Theophilus London. It was kismet. “We worked really quickly on that song [‘Flying Overseas’],” says Hynes. “Our brains were in similar places, musically. We were emailing each other, sending things we were listening to, and I’m pretty sure she sent the same song by SOS Band [that I’d sent to her], which is cool, because it was after that discussion that I wrote ‘Locked in Closets.’” Solange invited Hynes out to a house she’d rented in Santa Barbara in the spring of 2010 to work on production for the album. “It was kind of crazy for her to take a chance on me like that, because I was only just beginning,” he says. “I’d done stuff before, but usually home productions, because I was never really too confident.” True represents but a mere fraction of the material Hynes and Solange made together, whittled down to seven tracks to produce the most pure aesthetic through-line, and though Hynes’ style and predilections are written all over the EP, to give him the lion’s share of artistic credit, he feels, would be unfair. Even a song like “Bad Girls,” which Hynes recorded and released as a 7-inch well before Solange used it on True, in his mind, is still a collaboration. “I wrote it thinking about [Solange] singing it,” he says. “She calls it a cover, but I don’t see it [that way] because I’d heard her sing it, and there are certain things I do on that song that are only because of how she’d sung it,” he says. “I have full trust in her. She’s never done anything where I’m like, Are you sure you wanna do that? I’m always just like, Oh shit, that’s a good idea. I really love the tone of her voice. I think it’s so perfect for the music I’m always trying to create, the place I’m trying to reach.”

Hynes is also keen to help Solange realize her own vision, and on a chilly day at the start of the New Year, the two reunite in a midtown studio, accompanied by their wizardly bass player, DJ Ginyard, and a genial, bearded sound engineer. Their task is to transform “Looks Good With Trouble,” the brief, penultimate track on True, into an extended edit with freshly written verses from Solange and, tentatively, a guest verse from rapper Kendrick Lamar. In the vocal booth, Solange is improvisational and iterative, harmonizing with herself and layering airy flourishes, stepping out to hear the playback, and then going back in, jotting lyrics in TextEdit and adding and redacting like an editor might. As we walk to the train after the studio session, Imogene Strauss, Hynes’ manager, tells me that Solange had written to her and Hynes the week prior to say she wanted to go back into the studio to rework the song, and that she’d like to ask Lamar to get on the track and heard back from him almost immediately. It’s this kind of pull that reminds you of the access and power at Solange’s fingertips, but it’s the way she wields that it that is really more remarkable. She may be able to fly herself and a friend to an island getaway on a whim, but she’s also curious and clever enough to see the potential in a guy like Hynes, a scrappy but brilliant songwriter who used to play in a band called Test Icicles.

When I talk to Terrible Records’ Ethan Silverman over the phone, he has the bemused enthusiasm of a good friend and a super fan. “I think Dev is such a brilliant songwriter, but he’s also so quick to just put [whatever he’s working on] down and be like, It’s done,” he says. “Solange was able to push him even further and tweak his initial brilliant demo and just pump it up a little bit more. The collaboration between them just brings out a little extra for Dev—obviously for her, too. I’ve heard some of the demos that became Solange tracks, and you still know it’s the same song, but it’s just got an extra level of excitement, and that’s definitely Solange’s ear.” When you see Hynes performing a song he’s written for another performer, like Sky Ferreira’s “Everything is Embarrassing,” with just a microphone and a laptop perched on a stool on the stage, you get a sense of how mutual the benefits are for them both. Solange brings out a new level of professionalism and showmanship in Hynes, while his architectural sensibility may help her to reach a level—like Janet did in the ’90s—where her music will stand as the one, solid place you no longer see her older sibling.

Backstage at Bowery, Solange has changed into a punchier look—a skirt and blouse set with an enlarged net motif by Kenzo—and the rest of the band is complementarily suited, picking up accents of her kelly green and orange print and the purple bits on her chunky heels. Everyone congregates in the greenroom, and Solange invites Ginyard to lead them in a prayer, the mood as light upstairs as the anticipation is heavy below.

Mercifully, “Locked In Closets” goes off without a hitch, and the smooth shimmy Solange and Hynes dance on “Don’t Let Me Down” gets an even bigger response than it did last week. But the most impressive performance in the set will be “Cosmic Journey,” which the band never quite nailed in rehearsal and which Solange has decided to slip in at the last minute between “Looks Good With Trouble” and “Locked in Closets.” Within the first few seconds, it’s clear that the band has flubbed the difficult 3/4 change-up, and it’s not likely they’re going to recover. Solange muscles her way through the opening lines anyway, and hangs on for a few more, before throwing her hands up in the air. “All right, this isn’t working. Imma keep it real: We tried to learn this shit during soundcheck,” she says, backing away from the mic, as if to shake it off. “I knew my part, though! So fuck it, let’s dance!” Cueing up the next song without missing a beat, this is how she wins the crowd—not by doing what’s expected, but by doing what she pleases.