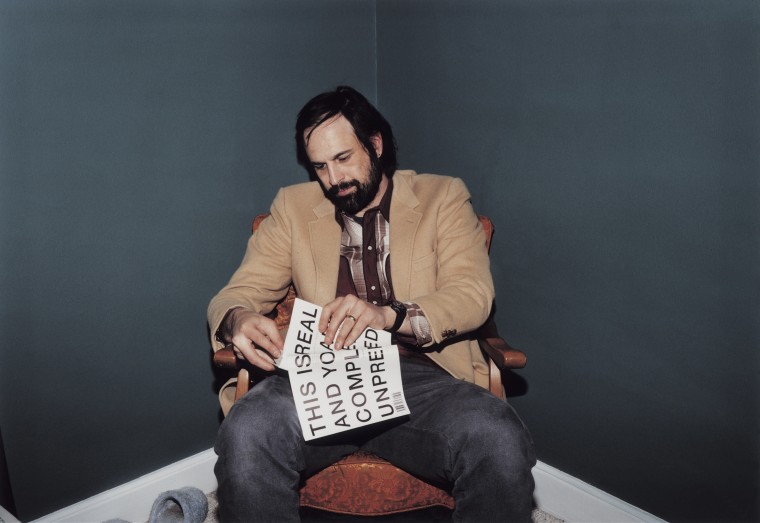

Michael Schmelling/The FADER

Michael Schmelling/The FADER

In the history of pop, any attempt to approach song lyrics as poetry — or vice versa — is often viewed with suspicion. In a poetry course I took in graduate school, my professor said that one of my poems “reads more like a rock song.” I didn’t need to ask him if he meant it as a compliment.

David Berman, who died yesterday at the age of 52, was one of only a few artists who was as celebrated for his poetry as he was for his songwriting. More so than fellow Jewish singer-songwriters Bob Dylan (whose words in a “poetic” context draw more scrutiny than when they’re set to music) and Leonard Cohen (whose verse and song lyrics differ from each other), all of Berman’s work — even his drawings — exist on the same plane.

Berman had a punch-line-esque take on the world. That doesn’t mean that he viewed everything as a big joke, but rather that he couldn’t encounter something straightforward without twisting it a bit so that it had a different texture. One of my favorite lyrics of his is from the 1994 Silver Jews song “Trains Across the Sea”: “In 27 years, I’ve drunk 50,000 beers / And they just wash against me, like the sea into a pier.” There’s the setup, the mechanical pleasure of routine beer drinking, and then the unexpected curve — the situation’s cinematic and symbolic equivalent, an image that beautifully corresponds to the same elegant manner of incremental decay.

From the early ’90s until 2008, Silver Jews was the vehicle for Berman’s songwriting. The name perfectly surrendered the tone: full of mystery, humor (“silver Jews” is slang for blonde Jews), and a love of esoteric musical history (the moniker was reportedly an homage to both the proto-Krautrock band the Silver Apples and one of the Beatles’ earliest incarnations). As an undergrad at the University of Virginia, Berman met and befriended Bob Nastanovich and Stephen Malkmus. The three of them moved to Hoboken after college, and Berman and Malkmus got jobs at the Whitney Museum of Art. By day, Berman would spend time leaning against the walls of conceptual art, and saw something singularly poetic in it: “I thought, “I need to find a way to lean against my own walls.”

Berman first gained attention from both the indie-rock community and his label, Drag City, because of his proximity to Malkmus and Nastanovich, as well as Pavement — the duo’s other, more famous band. As a result, throughout the ’90s Silver Jews were unfairly seen as a Pavement side project, even though Malkmus and Nastanovich didn’t always play on the albums and the bands shared few similarities. Whereas Pavement were cryptic and jagged, Silver Jews were loose but straightforward — a bar band with a charmingly puzzling lounge singer.

On the closing track to 1998’s American Water, “The Wild Kindness,” Berman famously sang “It’s autumn and my camouflage is dying.” Today, it reads as the veneer of happiness fading, revealing only crippling distress. But the chorus is a mantra of hope and unsentimental romance: “I’m gonna shine out in the wild kindness / I’m gonna shine out in the wild kindness / I’m gonna shine out in the wild kindness / And hold the world to its word.”

One of the visual touchstones of Silver Jews covers is that they’re all images of horizons, whether literal (a desert road for American Water) or symbolic (2001’s Bright Flight, where your drug-induced horizon doesn’t go further than your living room couch). I always took the visual signifier to mean that, no matter where you are, there’s always something beyond you — either physically, personally, or creatively. It’s a constant reminder that there’s more to the world than your ego.

The Chicago imprint Drag City is known for signing acts with a distinctly sideways approach to making art. Bill Callahan and Will Oldham are two singer-songwriters on the label with similarly wobbly, rootsy approaches, but Berman stood out for his humor and uncommon gift for language. I can remember exactly where I was when I first heard Silver Jews: During college, in a backyard in upstate New York, when the opening words of American Water came on. “In 1984, I was hospitalized for approaching perfection / Slowly screwing my way across Europe, they had to make a correction.”

The couplet is as unlikely as a miniature asteroid, backed by the kind of cozy country-rock that’s perfect for springtime, or the early stages of a barbecue. The title, “Random Rules,” felt like the perfect fit for the words as well as the song’s chorus: “I know you like to line dance, everything so democratic and cool / But baby, there’s no guidance when random rules.” It’s a simultaneously circuitous and direct way of saying that the best moments in life are a happy accident.

For me and my friends, Berman’s art was deeply relatable: allergic to plain-speaking bullshit, fond of jokes, attracted to the accidental wisdom of an inverted cliché, admiring of small-time thrill-seekers who were unfairly maligned as losers. The context in which we experienced his music was in the thick of the Iraq War, when we were about to enter adulthood in a country that was undemocratic and cruel; within the music of Silver Jews, as well as Berman’s poetry book Actual Air, you were introduced to someone who seemed to have waded through the despair of that world and survived it — with a sense of humor, a sharp eye, and a willingness to respond with compassion rather than repulsion.

As Berman got older, you could sense that it became harder for him to find compassion in his surroundings. His longtime drug addiction was documented in painful detail in this magazine — specifically, in a story about his 2003 overdose, where he tried to die in the Loews Vanderbilt Hotel in Nashville, where Al Gore watched the results of the 2000 election, because that’s where “the presidency died.” Even though he was beloved for his artistic contributions, Berman could never quite escape the psychological shadow of his father, Richard, whom you might remember from such ignominious campaigns as “The Current Minimum Wage Is Good” and “Unions Are Bad”. When Berman ended Silver Jews in 2009, it was messy: He took to a Drag City message board and publicly disparaged his father as a “human molestor” and “a world historical motherfucking son of a bitch,” the kind of reactionary and emotional English that you rarely heard Berman say or write.

For around a decade after that, Berman more or less retreated from the public eye, living in assumed domestic bliss with his wife and bandmate, Cassie, in Nashville. But this past February, I thought I saw Berman walking around the Art Institute at the Pitchfork Midwinter Festival, obscured by his trademark trucker hat and aviator glasses. At an art show and Circuit Des Yeux concert at the Drag City venue Soccer Club Club, I saw him again, and this time I knew it was him — but it was almost like a different person walking around in Berman’s skin, skulking near the entrance, walking in circles and muttering to himself. When a Washington Post story was published in June of this year, detailing Berman’s divorce and his living above Drag City’s headquarters, the profile seemingly reflected a broken person trying to piece himself back together.

A couple of weeks later, Drag City released the self-titled debut of Purple Mountains, Berman’s new band and first release in more than a decade. Backed by the Brooklyn folk-rock band Woods, Berman’s latest songs resembled shambling music about a person whose life is in shambles — the transmissions of a shocked brain. Berman’s words felt explicit and forthcoming, with choruses like “All My Happiness Is Gone” and lines like “You see the life I live is sickening / I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion / Day to day I’m neck and neck with giving in / I’m the same old wreck I’ve always been.”

It’s hard to see otherwise, but Purple Mountains doesn’t sound like someone giving in, as much as it does like someone who danced with oblivion and came out the other side ready to take on life again. It’s possible that that mindset didn’t stick, but Purple Mountains can still be used as a guide for digesting pain. On the album’s final song, “Maybe I’m the Only One For Me,” Berman repeatedly sings the title, which doubles as a lament for his newly single status; he wasn’t for everyone, but for the people he inspired, his harmoniously incongruous perspective was a reliable avenue to stay sane.