What We Owe Yasiin Bey

Looking back at the influence and complicated legacy of the artist once known as Mos Def.

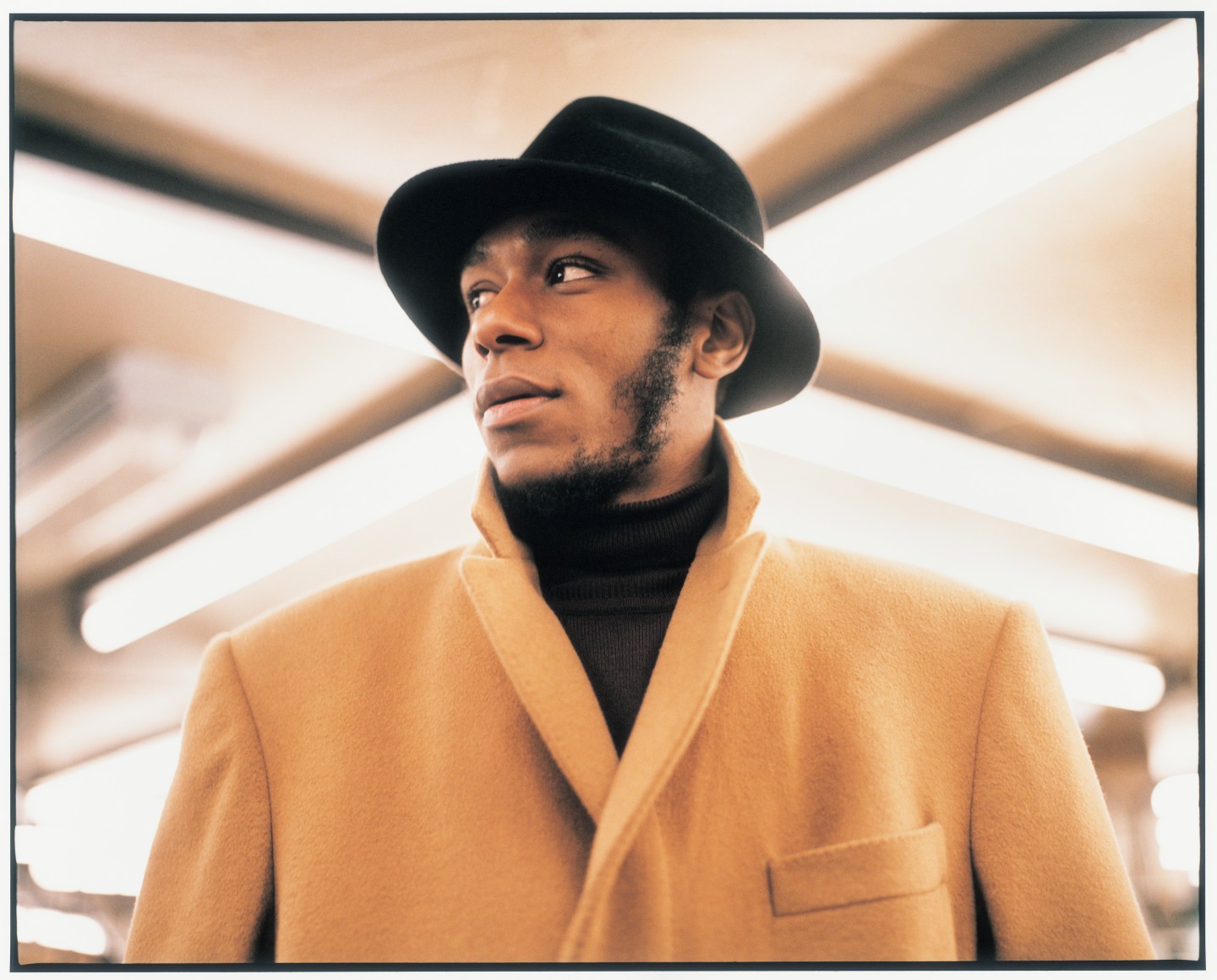

Yasiin Bey in 2000, from his cover story for The FADER

Yasiin Bey in 2000, from his cover story for The FADER

Morality in religion is fairly straightforward. Though the tenets of right and wrong vary from faith to faith, you alone are accountable for your behavior. But in art, the concept of morality is a bit more complicated. No one knows this better than Yasiin Bey, who launched his career as Mos Def in the 1990s by raising questions about rap’s creeping materialism and lack of social aptitude.

Bey initially provided a folk-like detour to heads who wanted more than just rhymes about Rolexes, giving listeners insight into everything from black pride (“Umi Says”) to the environment (“New World Water”). Then he spent the next 20 years as an enigma, pinballing between different genres, from rap to blues, while leaving a dense and convoluted body of work in his wake. With Bey set to retire from both the music industry (and Hollywood) in 2017 — a sad though unsurprising decision from a guy who was living off the grid (and occasionally trapped) in South Africa for the last three years — it seems fitting to reflect on his legacy and why hip-hop is so indebted to his art and activism.

In a time of extravagance, he showed us substance

Saviors are hard to come by, but in 1998, hip-hop found one in Mos Def with Black Star, his collaboration with fellow Brooklynite Talib Kweli. The album’s intro featured a quote from the legendary saxophonist Cannonball Adderley (“We feel that we have a responsibility to shine the light into the darkness”), and put in motion a movement that again popularized the now-hackneyed term of “conscious rap.” As Mase and Puff Daddy’s “Lookin’ At Me” hit No. 1 on the Billboard Rap Charts for the ninth week in a row, Black Star provided a necessary balance: the album’s themes swayed from civil rights to the corruptibility of corporatized music. On “Astronomy (8th Light),” Bey went with “Black like the planet that they fear, why they scared?/ Black like the slave ship belly that brought us here.” On “Children’s Story,” he rapped, “With liquor in his belly son, he made up the track/ But little did he know that his joints was wack/ The shiny A&R said ‘Great new hit, G!’”

The fact that the album charted at No. 53 on the Billboard 200 is a minor miracle considering how out of step it was with the music industry. In hindsight, this was a bold piece of counterprogramming, and many rap fans (smug purists, and otherwise) followed along. As VIBE’s Jeff "Chairman" Mao wrote in advance of Bey’s 1999 solo debut, Black on Both Sides —an album that covered topics including the crack era and how Elvis was a fraud who ripped off Chuck Berry — “[t]he uncanny quality of his vocal melodiousness has elevated him to underground savior status among progressive-minded hip-hop fans worldwide.”

He embraced creative left-turns, even when it wasn't commercially advisable

But Bey was uncomfortable being rap’s Liberator-in-Chief. He would joke about it years later during a talk at the 92Y in Manhattan: “‘Mos save hip-hop!’ Here I come to save your culturrrrre.” After Black on Both Sides, fans hoped for more of the same, but Bey turned to acting instead, starring in early ‘00s films Monster’s Ball, The Italian Job, and the miniseries Something the Lord Made, for which he received an Emmy nomination in 2004. By the time his second solo album The New Danger came out, five years after his debut, Bey had done a musical 180, presenting himself as more of a rock frontman than a rap superhero. As he told Rolling Stone, “[Fred Durst] and all those ‘Yo! Yo!’ white cats pissed me off pretty good. I wanted to make a rock record that really utilized both the elements of rock and hip-hop.”

Truthfully, this version of Bey wasn’t all that different from the artist he once was, but the music was weird enough to have fans searching for the “old Mos Def.” While Bey certainly didn’t invent the concept of rappers exploring new ideas and sounds, his creative left-turns sent a clear message to a new generation of talent: Do what inspires you and don’t apologize for it. No wonder Kanye West and A$AP Rocky — two artists who are celebrated for their unpredictability — consider Bey a mentor.

He proudly gave fans a window into Islam

Though Bey’s work has often moved in experimental tangents, one thing that’s remained consistent is his devotion to his religion. In the midst of worldwide Islamophobia, Bey has proudly put his Muslim faith on display, starting each of his albums by reciting the Arabic phrase “Bismillah al-Rahman al-Rahim” — which loosely translates as “In the name of Allah, the beneficent, the merciful” — and speaking extensively about his beliefs in speeches and interviews.

In 2011, seven years after The New Danger, he underlined his commitment by officially dropping his Mos Def moniker for Yasiin Bey, the name his friends and family had been calling him since the late ‘90s. While Bey has never explicitly stated why he chose Yasiin, its connection to Yāʾ-Sīn, the 36th surah of the Qur’an, is apt. In this chapter, three divine prophets are sent to a village to teach non-believers about the significance of God. But the townspeople scoff at their message, calling the prophets liars. As Muhammad Asad states in his 1980 book The Message of The Qur’an, one of the surah’s primary lessons is “the problem of man’s moral responsibility.”

Like the prophets, Bey considers all of his work a conduit for change, and himself a moral arbiter who warns the masses, not of God, but of the world’s many injustices. For example, in this 2013 video he voluntarily goes through a Guantanamo Bay force-feeding procedure. Earlier still, in an appearance on Real Time with Bill Maher in 2009 — one that he was later mocked for — he said, “The nuclear club should be disbanded because America has proven that there’s no country who’s really going to be responsible with this shit. You can’t get on Iran’s back and say, ‘You can’t have nuclear arms, but we can.’ Oppenheimer was right: we should have never built this shit to begin with.”

Above all, he provided a reminder to stay true to yourself

In 2009, Bey dropped The Ecstatic, a return to the purist rap roots his fans had been clamoring for. It also served as a welcome respite from his previous effort, 2006’s True Magic, which had been released to fulfill the end of his contract with Geffen and sounded like it was recorded on a busted cassette tape.

And then Bey went into hermit mode. Save for the occasional freestyle or cause, he seemed content with living a quieter life than the one his listeners so desperately wanted him to lead. As he once told XXL with a laugh, “I haven’t been away. I’m just not on certain radars. Cause I’m not jumping in the Gladiator ring to be like, ‘I smite thee!’ Like, you know… I’m relaxed.”

Bey recently released December 99th, a project with producer Ferrari Sheppard, and is reportedly set to drop two additional albums later this year: As Promised, a collaboration with Mannie Fresh, and Negus In Natural Person. Then he’ll call it quits, returning to the reclusive persona he’s been cultivating since his early 20s, when he was in Urban Thermo Dynamics, a rap group he started with his siblings. Though Bey has spent the last 20 years providing a prophetic blueprint for hip-hop, art, and the world at large, his most enduring prophecy might have just been about his own career. As he rapped on UTD’s only album back in 1994, “Ever since I was small I played the wall/ The loner type, even as a little tike/ While the other little kids were out at play/ I was home wishing for a rainy day.”