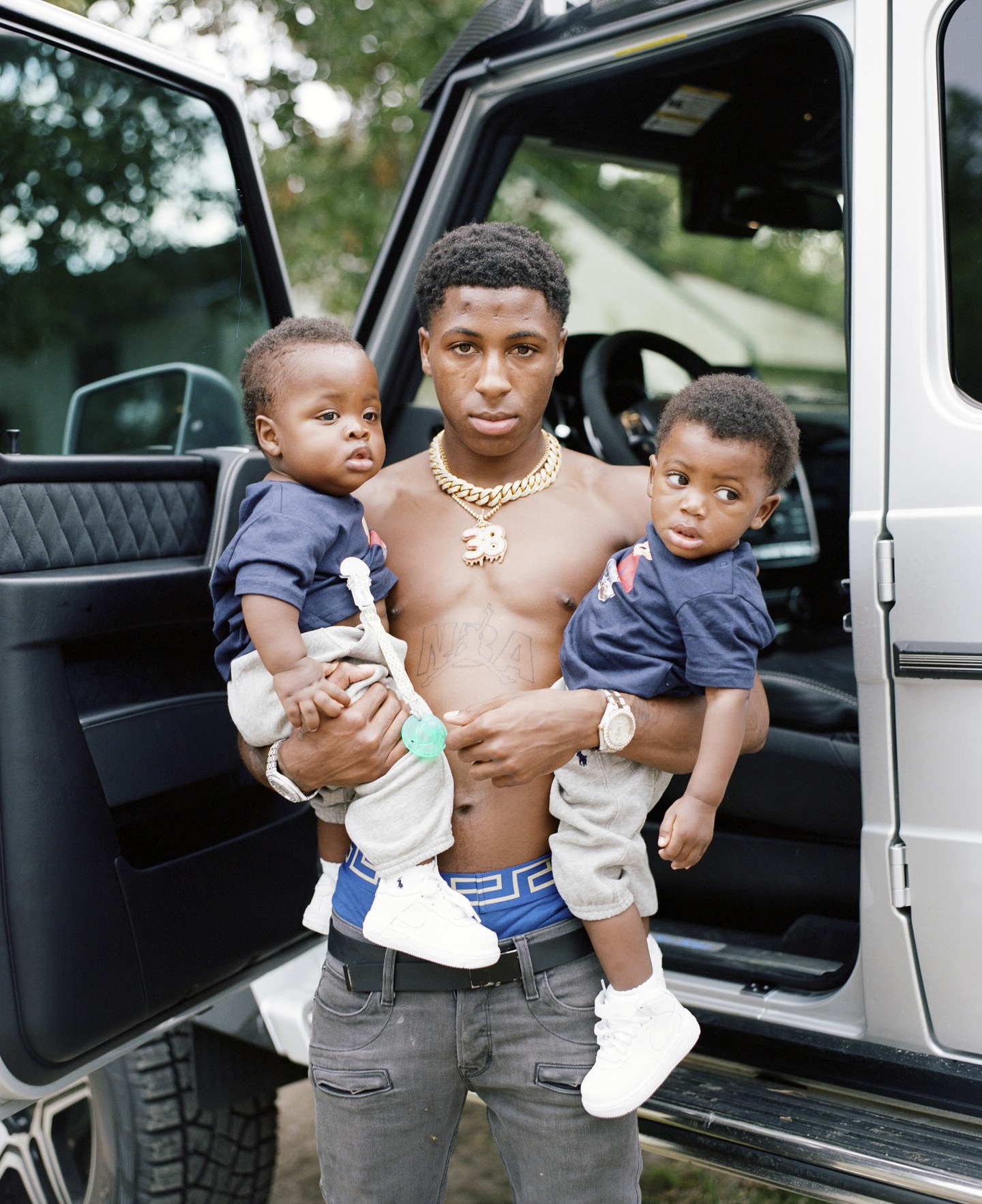

YoungBoy Never Broke Again has a loyal French bulldog named Naomi, who follows him around, stopping every so often to make a small puddle of pee on the marble tiles of a glitzy clothing store in downtown New Orleans. His 1-year-old sons, Kayden and Kamron, sit on a display case nearby. He picks up both babies to plant kisses on their cheeks, then hoists the children over his shoulders and sniffs to his left and right — both of their diapers need changing. YoungBoy hands them off to Montana, a burly 31-year-old who, for the past year and some change, has done a little bit of everything for him. One after the other, Montana lays the babies on the black leather bench that customers normally use to try on expensive shoes and swaps out their soiled diapers for clean Pampers.

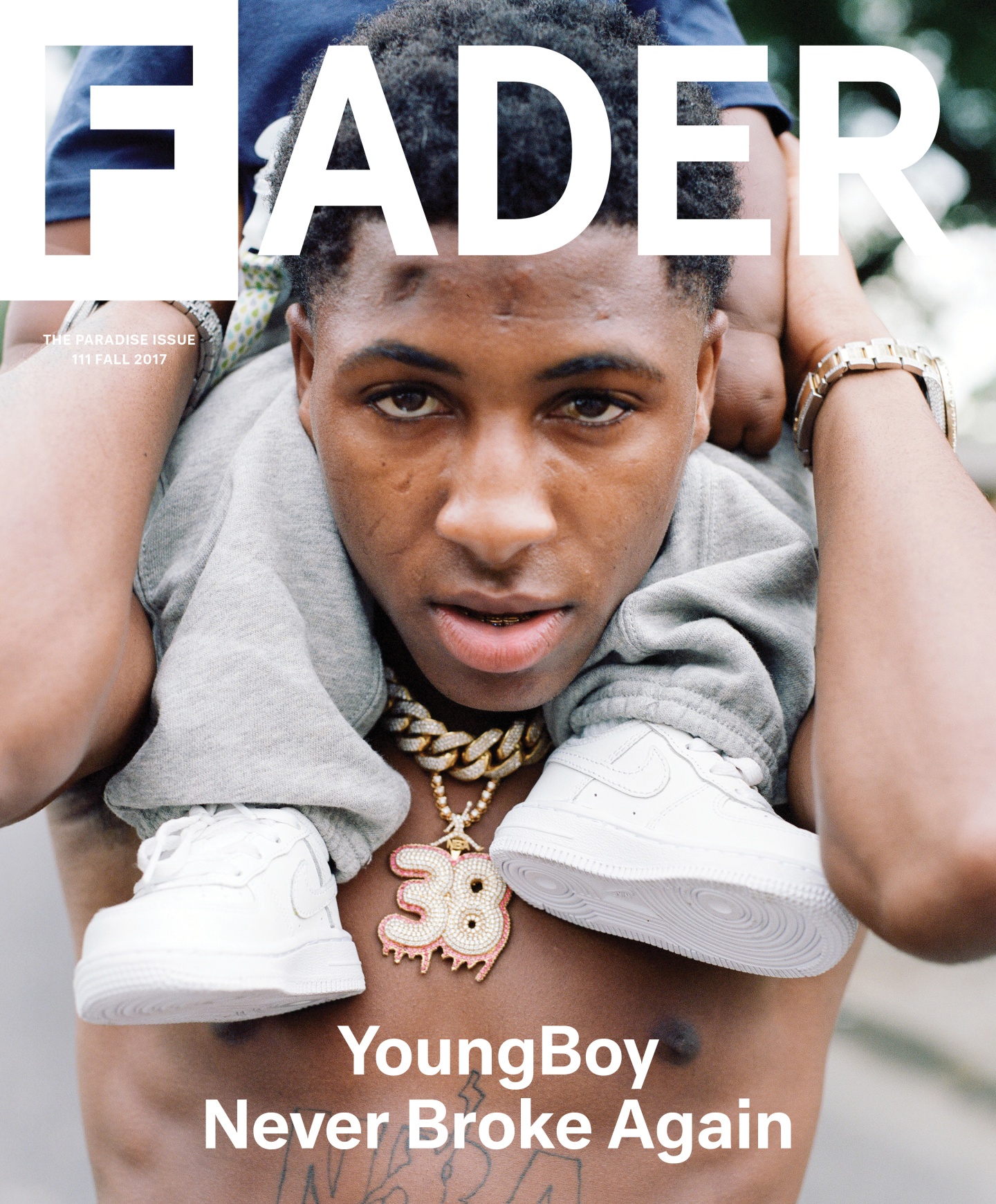

YoungBoy is slim and muscular with a long torso that seems to make up the majority of his body. His brown eyes are several shades lighter than his skin and tapered hair, at first giving off the appearance of youthful innocence. But the three deep scars engraved into his forehead, from wearing a halo brace after breaking his neck as a toddler, make him look much older than 17.

He says he never wears the same outfit twice, and he usually throws most of his clothes into the crowd during his shows. A video taken after a recent performance suggests that he might not always let go of his garments by choice: fans chase him through a parking lot and nearly strip off his pants as he tries to climb over a fence. Today, he settles on a long-sleeve blue-and-white-striped Comme des Garçons Play shirt, Balmain jeans, and a pair of Raf Simons adidas, then makes his way to the red SUV parked outside.

A small group of people moves in close as he climbs into the passenger seat. One man with dreadlocks poking out from behind a visor begins freestyling rapidly — “Katrina when I lost my mind…” — until he is lightly pushed aside by a group of eager fans. A teen who seems to be around the same age as YoungBoy approaches the car. He’s wearing a black polo shirt tucked into baggy black slacks and looks like he’s on his way to a shift at a French Quarter restaurant. “2012, Ryans Detention,” he tells YoungBoy, referring to the juvenile facility in Baton Rouge. “I was there with you.”

In November 2016, YoungBoy, born Kentrell DeSean Gaulden, was taken into custody by U.S. Marshals before a performance in Austin. He was accused of jumping out of a vehicle and opening fire on a group of people on a South Baton Rouge street and charged with two counts of attempted murder. The incident had come just hours after 18-year-old Keondrae Ricks, a friend who rapped under the name NBA Boosie, was shot and killed a few blocks away. Because YoungBoy was 17, he was eligible to be tried as an adult in Louisiana. After six months at Parish Prison awaiting trial, he pled guilty to the lesser charge of aggravated assault with a firearm and was released on $50,000 bail pending sentencing.

In late August 2017, YoungBoy appeared in front of Judge Bonnie Jackson at the 19th Judicial District Courthouse in his hometown of Baton Rouge. In what a courtroom reporter for The Advocate described as a “gripping but respectful back-and-forth exchange,” the judge sentenced him to a ten-year suspended sentence with three years of probation, meaning if YoungBoy violates the terms he’ll return to prison to serve the full sentence. “I was trying to tell her like, I’m changed and I’m trying to do better,” he says, summarizing his conversation with the judge. “I’m trying to do the right fuckin’ thing. I just can’t do stupid shit. But it’s scary — you be scared to do anything.”

At the time of his arrest, the rapper — then going by NBA YoungBoy, before potential copyright issues were a concern — had been approaching stardom. He had released three projects in the span of six months, which led to a five-album, $2-million deal with Atlantic, signed in October 2016. Behind bars, his output was stalled but his profile only got bigger, and since his release YoungBoy has continued to gain ground. Tomorrow night in New Orleans, he’ll perform at Lil Weezyana, Lil Wayne’s third annual celebratory festival for his hometown fans. The show will be YoungBoy’s biggest to date.

But what’s weighing on him more immediately, more than the concert and even the looming threat of slipping up and going back to prison, is the fact that, under the terms of his probation, he is expressly banned from being around Lil Ben. Ben is one of YoungBoy’s closest friends in the world — the two have known each other since they were babies, and he has been present at the rapper’s side in nearly every music video he’s ever released. “He’s too important,” YoungBoy explains. “I think the judge knew she was hurting me when she said that.” He jokes that he’s going to pay for Ben to get face-altering plastic surgery so they can continue to navigate YoungBoy’s growing fame together, without court interference.

Baton Rouge is home, but it’s also a small city where flying under the radar is impossible and the slightest hint of fame brings jealousy and hate. “It’s crabs in a bucket,” YoungBoy says. So, since his release from Parish Prison, he’s made New Orleans his temporary headquarters, moving between rented condos and hotel rooms when he’s not on the road. Being in the city that birthed Louis Armstrong and Dwayne Michael Carter, Jr. puts a small amount of distance — about an hour’s drive — between him and the state capital while he awaits court approval to move out of Louisiana for good: once his probation is transferred, YoungBoy says he plans to move to Atlanta, rap’s expanding epicenter, to focus on his music. “I’m leaving and never coming back.”

Tonight, in preparation for Lil Weezyana, he’s staying at the Hyatt Regency. After arriving at the hotel, he gets a call and wanders away to speak in private. Two of his Never Broke Again brothers, 3Three and Boomer, were arrested the previous day on separate, unrelated charges. Their clique is mostly a tight-knit collection of childhood friends who call each other family, but, following YoungBoy’s rise, a few others have picked up the mic as well. “Three’s in central booking,” YoungBoy reports when he gets back. “Cold and hungry.”

YoungBoy was born in North Baton Rouge in October 1999, the middle child of three. “I come from a rare place,” he says. “It’s a different culture, different atmosphere, police crooked. Different emojis, and when I say emojis I mean personalities.” He started writing songs at the age of 7, inspired by his mom, who herself briefly rapped. When he was 8, his father was arrested and sentenced to 55 years in prison for a robbery gone wrong and his mother moved out of the neighborhood, leaving YoungBoy with his maternal grandmother.

“I got my way with my grandma,” he says. “I used to get whoopings with my mom, but my grandma spoiled me.” When his grandma passed away from heart failure in 2010, 3Three’s family took him in. Three’s mother Monique, who YoungBoy calls “Mom,” remembers the two boys getting into all sorts of trouble in pursuit of their rap dreams. At one point, she says, they stole car batteries out of 18-wheelers and sold them in the hopes of paying for time in the studio.

After 8th grade, YoungBoy stopped showing up to school. “I wanted to be a rapper and I couldn’t focus and do that,” he says, pausing. “I didn’t even have the clothes for that shit. I really felt like I wasn’t smart enough, so what the fuck I’m there for?” He bought a microphone from Walmart and downloaded recording software to start making songs on his own, adopting the NBA acronym as a motivation to make “Never Broke Again” a reality. It was Monique who paid for his first real studio session shortly after. One of the songs he recorded, “Range Rover,” ended up on his first mixtape, Life Before Fame, released in 2015. On the song a 14-year-old YoungBoy sounds preternaturally dejected and world-weary, his voice nasal and noticeably higher pitched as he sings, “I’ma keep it in the streets until the game over/ Searching for better days till the pain over.”

“I come from a rare place. It’s a different culture, different atmosphere, police crooked. Different emojis, and when I say emojis I mean personalities.”

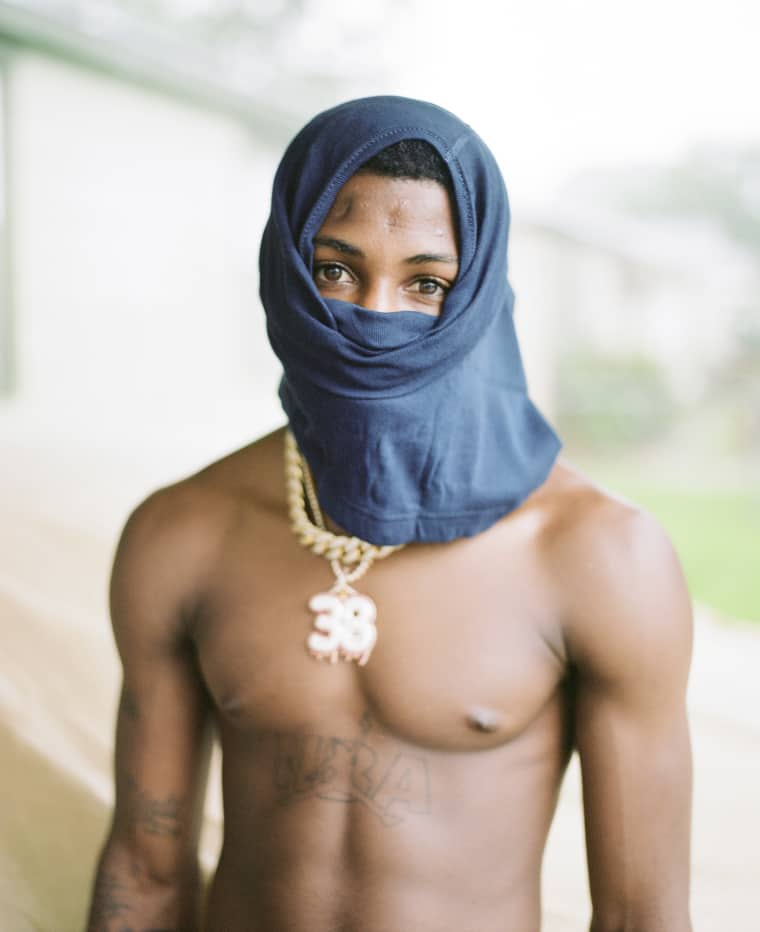

Just over a year ago, YoungBoy was sleeping on an air mattress at Montana’s house. At the time, Montana served as YoungBoy’s manager, booking agent, and financier, and the two would drive all over the South, sometimes spending up to 12 hours in the car, to perform for between $500 and $1,500. His fan base grew steadily in the region, but his numbers exploded with the release of the video for “38 Baby,” a song named for the street where YoungBoy grew up. The video shows him riding around Houston, clutching a .38 pistol. Guns were a prolific fixture in all of his early videos but, since his release, YoungBoy and his go-to videographer David G have focused more on narrative. A recent video for “Wat Chu Gone Do” is set on the block where he grew up and casts his little brother, Ken, as a younger version of himself, picking up the writing pad for the first time. These days, every video they put out quickly hits a million views.

YoungBoy has now released seven projects in total, each full of intensely personal songs about betrayal, pain, revenge, and, in spite of it all, overcoming. AI YoungBoy, released in August, shows significant developments in his songwriting ability and an ever-improving mastery of melody. YoungBoy says he plans to release one more mixtape before focusing on his debut album. In an industry landscape of pushed-back release dates and shelved records, signing to a major label can be treacherous, but YoungBoy sounds optimistic. “That was like a dream come true,” he says. “That ain’t like me signing to no rapper. And they gave me that fuckin’ bag when I was 16.” For YoungBoy, the Atlantic deal meant the immediate opportunity to take care of his family and a way out of a life being lived half in the streets and half in the studio. It meant pursuing a career.

It also affords him more exotic opportunities. In an Instagram video, posted the day before we meet and since deleted, YoungBoy stands in front of a large mansion, facing the camera and holding a baby tiger by the scruff of its neck. By the time I get to New Orleans, the tiger is gone — she was driven overnight to a new home with another rapper who “has the habitat for her.” YoungBoy suggests that she’s “probably eating Wingstop.”

There are layers of people always surrounding YoungBoy. At the Hyatt, 19 floors above the rest of New Orleans, he lays the outfit he just bought next to a thick Cuban link, a chain that bears a diamond-encrusted “38,” and two shimmering watches. Montana scrolls through his phone with Kamron in his lap. Fee Banks, YoungBoy’s current manager, paces back and forth, answering phone calls seemingly every other minute.

Fee, perpetually calm and collected, is nearly 40 but he looks much younger, like he’s been closely sticking to the Pharrell Williams skincare routine. He’s something of a legend in Louisiana rap; in the mid-2000s, he helped Lil Wayne start his Young Money label, and he managed Kevin Gates up until the rapper signed a deal with Atlantic in 2013. Now, he’s tasked with helping YoungBoy reach the same levels of success. YoungBoy is constantly testing Fee’s boundaries. On the way from the clothing store to the hotel, the rapper handed a teenager a $100 bill to throw a melted cherry sno-ball onto the hood of Fee’s brand new Mercedes-Benz G-wagon.

Stripped down to his Polo briefs, YoungBoy heads for the shower and, once inside, tells me to come into the bathroom to talk in private (“I don’t give a fuck, I was just in the jailhouse”). His exchange with the judge a few days before, among other things, is still weighing on his mind.

“She tried to make it seem like my music’s making people die,” he says while the water runs. “That’s exactly what she said to me in court.” YoungBoy is quick to dismiss this accusation, one that has been leveled against street rappers forever. He says he’s speaking about his lived experiences — in a city, state, and country where countless structures have failed him — not suggesting that others follow his lead. He’s more focused on how his music will be able to improve lives, particularly for those close to him. “I got fuckin’ children, I got a family that depend on me, I got a momma who don’t like to work, I got a baby momma that got three kids, two of ‘em from me,” he lists off. “Everybody depend on me. I can’t fuck up. I ain’t the only person that I’m hurting. If I was given a billion dollars to do life in jail, I’d do it and give that shit to my fam.”

When I ask if he feels like he ever got the chance to have a childhood himself, he stops to think about it for a moment. “Not really. I still wanna do a lot of kid shit just to get my mind off the streets,” he says. “Music get my mind off the streets, but you know what I mean. I gotta make this shit happen. I can see, I can hear, I can smell, I can speak, I can touch — ain’t no excuses. Shouldn’t shit hold me back but death.”

He continues showering in silence for a while before cutting the water off. “Reach me that towel.”

"I can see, I can hear, I can smell, I can speak, I can touch — ain’t no excuses.”

YoungBoy has only been in New Orleans for two hours, but he already wants to return to Baton Rouge. A car full of friends and family has just arrived from there; no one else wants to go back, but YoungBoy seems increasingly unsettled in his current surroundings and they reluctantly give in to the rapper’s impulses. “What is there to do in BR?” Fee asks him, irritated. “What is there to do down here?” YoungBoy quickly snaps back.

On the road, rush hour traffic has taken hold of New Orleans’s Central Business District, and the sun is high, reflecting off the glass windows of the office buildings that line the street. YoungBoy scrolls through Instagram, abruptly turning around to ask everyone else in the car if they think another rapper, a popular contemporary of YoungBoy’s, has been sending subtle shots at him. “I’ve been feeling like something ain’t right with him ever since you got out,” says Jiggalo, an NBA comrade with a narrow face and wispy soul patch. Dump, a stout 28-year-old who’s YoungBoy’s driver for the day, agrees. “They asked about you on his Live, and he was acting funny,” Dump says. YoungBoy turns back around and begins recording. “Don’t be on Instagram with that pussy ass shit, we in two different states,” he snarls into his phone camera. “I’ma keep it a hundred, I don’t like you.”

Over the last few months, many have warned YoungBoy about the dangers of staying close to Baton Rouge. After his release from prison, the city’s rap hero Boosie BadAzz, who also moved away after his release from prison in 2014, took to Instagram to deliver a message to the young rapper. “Welcome home,” he wrote under a blurry photo that shows YoungBoy sitting in the backseat of a car, smiling, minutes after walking out of prison: “Leave BR asap.” In the beginning of his video for “Untouchable,” the first song YoungBoy put out following his release and his first song to chart on the Hot 100, he gets a FaceTime call from Meek Mill, who bluntly warns, “You gotta move or you gon’ die.”

The car continues to inch through traffic until, at a red light, a man walks up to the passenger window from behind. He taps his knuckles against the glass. YoungBoy recognizes him: the guy has amassed something of a social media following for chasing down famous rappers and freestyling for them on camera. Earlier this summer, a video of YoungBoy executing an acrobatic spin move to avoid him was picked up by a few rap news sites; afterward, the man had taken to social media to diss him.

YoungBoy swings his door open, and Dump puts the car in park. The SUV is suddenly empty. Standing in the middle of bumper-to-bumper traffic, as people in their cars look on, Dump forcefully shoves the man back toward a car stopped behind, where two of the freestyler’s friends stand with the doors open. One of them has his hand ominously in the door pocket. The light turns green and cars begin to honk, and Dump grabs YoungBoy and shepherds him back to the SUV as the other men retreat. For the next 15 minutes, until Dump steers the car out of Orleans Parish, they all talk feverishly about what could’ve happened.

For the rest of the drive to Baton Rouge, past swamps and strip malls, YoungBoy plays unreleased song after unreleased song from his iCloud library, where he estimates he has around 100 tracks (“too many to keep in my email”). There’s a towering collaboration with Offset, a verse on a song with A-Boogie and PnB Rock, and a catchy duet with Lil Yachty. YoungBoy painstakingly resists classification, sounding equally adept on street anthems and love songs. On the 2016 track “They Ain’t With Me,” he offers a rare but telling namedrop: “I ain’t never had a role model, watched Chief Keef growing up.” Like the Chicago rapper, who moved to L.A. after repeated run-ins with the law, YoungBoy’s sound grew up at home, but, like Keef, he knows he needs to leave.

YoungBoy is operating on a timeline of his own creation — he dismisses peers, who he doesn’t call out by name, as “weird ass rappers with weird ass fan bases,” but also insists that he’s “new school.” And yet the heart of his music is in the direct lineage of his Louisiana predecessors, echoing the everyman versatility of Boosie, the melodic leanings of Kevin Gates, and the soul-bearing testimonies of slain Trill Ent. rapper Lil Phat. The production he chooses is often bluesy — MIDI guitar riffs, deep bass lines, and piano chords feature prominently — and YoungBoy uses them to tell stories of both trauma and triumph. He raps with precision, relying on the gravity of his words instead of colorful language. YoungBoy is similarly understated in explaining his own process: “I just know what I go through, and I know how to speak on it in an interesting way.” Fee says all of the teenager’s best songs come together when he kicks everyone else out of the studio and records by himself.

Dump exits the highway and, with YoungBoy’s encouragement, whips through an intersection as the light turns red. He makes a left onto an unmarked street and pulls into a gravel driveway in front of a blue house that’s pushed far back off the road into a thicket of trees. Across the street, a home is boarded up and overgrown, and two pit bulls tied on long chains watch us from the driveway next door. Dump’s family has lived on this small block in the Valley Park neighborhood for as long he can remember — his grandmother had 18 kids here.

One of Dump’s uncles shows up carrying two big bags full of Popeye’s and lays out the spread on the hood of the red SUV. While everyone else grabs chicken, biscuits, and red beans, YoungBoy feeds Kamron and Kayden small bites of mashed potatoes. “I try to keep my kids with me everywhere I go,” he says. His third son, Kamiri, who’s 2 months old, is at home with his mother. When he gets enough money, YoungBoy plans on buying a house on a big piece of land with enough room for his children, their mothers, and the rest of his family. “It’d be our own world,” he says. (Since this story was reported, YoungBoy found out through a paternity test that he has a fourth son, Taylin, who was born in March.)

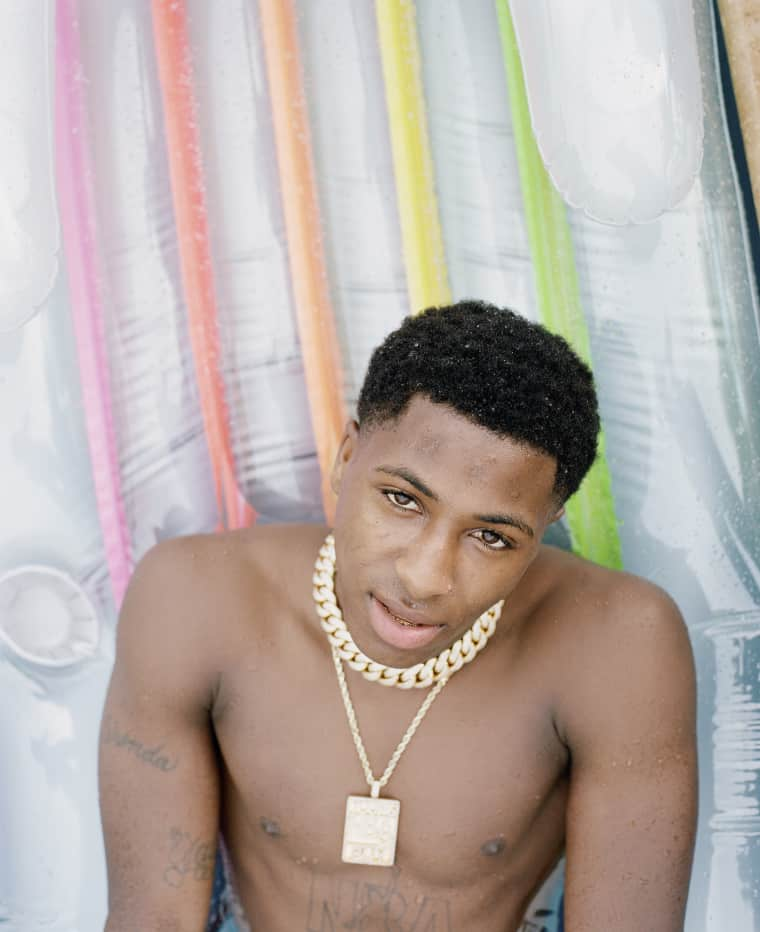

More and more cars, all blasting YoungBoy’s songs, pull up on the street as the light begins to fade. When another one of Dump’s uncles produces a case of Powerade from the trunk of his car, YoungBoy gets a devilish look in his eye. He immediately unscrews one of the bottles and sprays the drink all over Montana’s shirt with one quick motion. This sets off an all out war; YoungBoy relentlessly chases down anyone within his reach, drenching them with the sugary liquid, only to be run back down the block when his latest victim gets fed up and picks up a bottle of his own. The Powerade fight ends when Dump’s had enough; he picks up two bottles and sneaks up behind YoungBoy, pouring the contents of both over the 17-year-old’s head.

Soaked and sticky, YoungBoy walks back to the driveway where the SUV is parked. Kayden and Kamron both sit in the front seat of the car with their bare feet dangling over the leather. The hum of insects in the trees around us, background noise at first, has steadily gotten louder. The shirt he bought earlier in New Orleans lays discarded on the gravel, and he picks it up to wipe the Powerade from his eyes. When I ask why he wanted to come back to Baton Rouge so badly, YoungBoy shrugs his shoulders, vaguely gesturing at the street in front of him, “This is me.”