Jonathan Williamson

Jonathan Williamson

By the mid 1990s, Danny Elfman was one of the world’s most recognizable musicians. He’d become Tim Burton’s go-to composer, penning iconic scores for Batman, Edward Scissorhands, and The Nightmare Before Christmas; had his own scores chopped up into a critically acclaimed best-of album called Music for a Darkened Theatre; and, of course, seen his theme for The Simpsons turn into one of the most familiar pieces of music in American history.

But when he left his successful new wave band Oingo Boingo in 1995 to focus fully on his compositions — which proved sensible; in the next three years alone he’d scored Mission:Impossible, Men in Black, Flubber, and Good Will Hunting — he was leaving some business unfinished in pop songwriting. Over the quarter century, he moved even further away from rock ’n’ roll, instead composing standalone pieces of contemporary classical music.

But in late 2019, when Coachella’s organizers asked Elfman to perform at their festival the following year, he went back to the well. He prepared an inventive medley of movie music and Oingo Boingo reprisals, as well as a dark instrumental track titled “Sorry.” When the world shut down and Elfman quarantined with his wife and son outside Los Angeles, more songs poured out. Thus was born Big Mess, a double album of ambitious chamber goth far removed from any of his past projects, and a collection of songs that would eventually seep into Elfman’s Coachella set when it finally went ahead this past April.

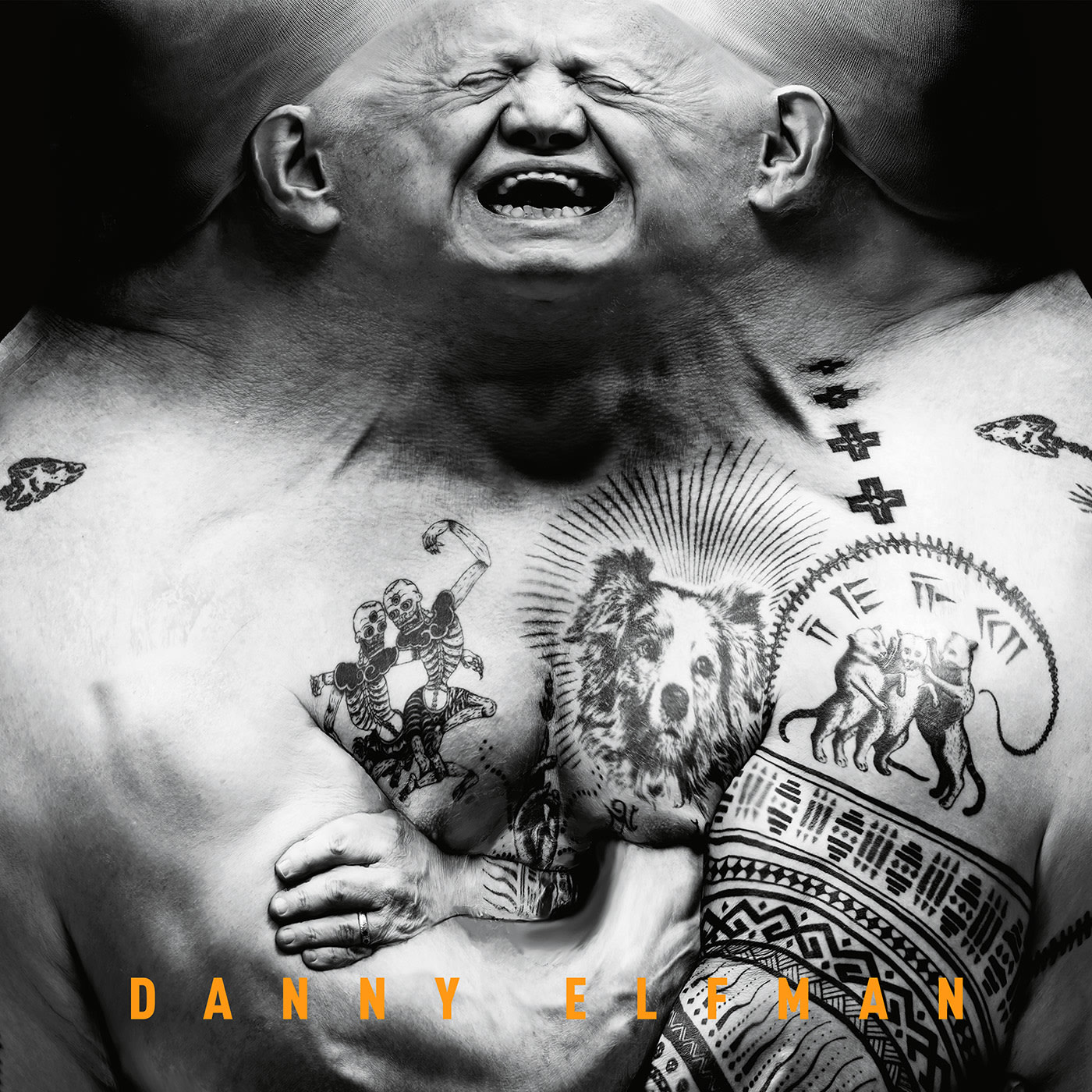

Then, in another uncharacteristic turn, he let go of his new tunes to be remixed and covered by a shockingly motley group of musicians. Bigger. Messier., out this past Friday, places features from Trent Reznor and Iggy Pop next to total reinterpretations by Xiu Xiu, Boy Harsher, and Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith. It’s a chaotic ride that’s impossible to explain on paper but a pleasure to listen to nonetheless. On the eve of its release, The FADER’s Raphael Helfand spoke to Elfman about his new project and some other things that make him happy, including low-budget horror movies, his tattoos, and his daughter Mali’s forthcoming first feature film.

This Q&A is taken from the latest episode of The FADER Interview. To hear this week’s show in full, and to access the podcast’s archive, click here.

The FADER: Big Mess came out about a year ago. How did the reception of that record differ from your expectations?

Danny Elfman: I didn’t have any expectations. I knew I was coming out with a weird thing that didn’t fit easily into any niche and was gonna be a marketing nightmare, so I was happy to find any audience at all.

You’ve talked about how making this album helped you realize you can do things with your voice now that you couldn’t when you were younger. What was it like to shake the dust off?

At first, I wasn’t sure how to approach it. The only singing I’d done since ’95 has been doing Nightmare Before Christmas concerts live for the last eight, nine years, so Jack Skellington was the only voice that I had used that decade. It started with “Sorry,” which was like an angry rant. It felt really good to be using my voice again — and not in a theatrical, Jack Skellington manner.

As I started doing more songs, I wasn’t trying for anything. I would have an idea for a song and start working my parts and see, “Oh, that’s interesting. I could do this.” I knew I wasn’t gonna write anything really high for myself. Back in the old Oingo Boingo days, I wrote for the very top of my range, which would disappear quickly when I was on the road. When I was doing “True,” I started getting into the groove, thinking, “I actually couldn’t have done this song 30 years ago.” I was finding an edge in my voice that I used to try to force.

On a similar note, what was it like returning to the songwriting medium after so many years of composing on a grand, symphonic scale?

It wasn’t intentional. I hadn’t thought about doing a record. I only thought about doing some songs because I accepted this Coachella show. I said, “Alright, I’ll do some film stuff and I’ll revamp some Oingo Boingo stuff.” I had two new songs I was gonna premiere, but I never thought about doing more. But once I opened that Pandora’s box, I couldn’t close it. I went into isolation, and before I knew it, not only did I finish “Happy” and “Sorry” — 16 more came out. It was all unplanned, but I think it had to happen. As soon as I put my voice to “Sorry,” I realized I had so much venom in me that if I didn’t let this shit out, it was not gonna be good.

Having grown up hearing your movie scores, it was a bit of a shock to hear you playing these strange industrial rock songs. But after listening more, I can see how the maximalist impulses that created your best scores are present in these songs too. Do you consider yourself a maximalist?

Clearly, I’m not a minimalist. Occasionally for film, I do a minimal style, but I obviously love laying it on hot and heavy. When it came to the songs, I’d been toying with the concept of combining rock band and orchestra in a way that I’m not used to hearing in rock songs. Usually, orchestra is for embellishment. I wanted to experiment with orchestra as a rhythm instrument, part of the engine of the song, and that became Big Mess.

You’ve called yourself an obsessive. That’s easier to disguise in an immersive film score where the music is working in service of a visual narrative. It’s much clearer on Big Mess, where it feels like you’re pushing each musical theme and lyrical idea to its logical conclusion. How do you turn that impulse into a constructive creative process?

The discipline with the songs, for me, was not overworking them, because I do have that obsessive part of myself. When I’m writing symphonic works, I try to find all the harmony and the counterpoint in everything. With the songs, I wanted to try to keep it more spontaneous, so the discipline was laying it down quickly, getting the idea across, and not going back and reworking it. I wrote and recorded all my demos between April and August [2020], and I could have gone another year on them if I let myself get into that mode. But then it would lose some of the freshness, so I didn’t go that way.

Moving on to Bigger. Messier., was it difficult for you to let go of your work after all these years being the sole auteur of your music?

It started with Stu Brooks, my bass player, asking if I’d be open to it, and I was like, “Oh yeah! But who’s gonna wanna do my shit? No one’s gonna wanna touch it.” Next thing I know, I’m on the phone with Squarepusher, like, “You know who I am?” He was the first, and I tried to give the same input to everybody, which was no input: “Just do your fucking thing. Don’t try to please me.” The pleasure in this whole experience, I realized, was letting go and finding creative people [and] having no idea what to expect from these extremes: the laid back stuff that HEALTH did, the really aggressive stuff that Zach Hill and Machine Girl did.

Then the second phase was, “Would you be open to anybody else vocally approaching some of the songs?” I’d mentioned Blixa Bargeld because I’m a fan of Neubauten, and Iggy Pop’s name came up, and I was like, “He’s not gonna want anything to do with it.” I was astounded when [he said yes], and Trent [Reznor] was sending tracks back, and Blixa [Bargeld] said, “Sure, I’d love to.” It’s like the icing on the cake on top of the icing on the cake.

The whole year after the album coming out became [about] letting go, giving up control. I’m such a control freak with my orchestral music. I’m probably one of the only composers who need to get hands on the faders when we’re mixing. Faders are my life. I can’t even remember a time before my fingers were on faders. I’m a control freak, and the pleasure here was giving up control, and I loved it.

You picked a wild group of artists to remix and cover your songs for this album. Were there any criteria you had for the folks you reached out to?

Just respect. Stu started working with my creative director [Berit Gilma] on the project. She’s really into electronic music, so she and Stu started brainstorming and sent me lots of stuff, because I needed some education. I’d get really excited: “The Locust? Let’s try it! Boris? I love it!” And Ghostemane. Now I’m addicted to Ghostemane Radio on Spotify.

You wouldn’t know it from Oingo Boingo, but I was always a fan of Nine Inch Nails, Tool, Neubauten. What I listened to wasn’t necessarily what I was doing. My band was great, but that wasn’t what we were. So getting into some really intense stuff with some of these artists, I loved that.

It’s interesting to think about Trent Reznor’s trajectory from rock music to film in relation to yours. Have you tracked his career through the years?

Definitely. Over the years, I worked on films where the producers said, “Can we get that Nine Inch Nails sound? I’d go, “Nope, we’re not going there. If you want Nine Inch Nails’ sound, get Nine Inch Nails.” It’s a sound there was a real thirst for in films, [so] I was curious when I heard Trent was [scoring] a movie if that’s what he was gonna do. My respect for him was already as high as it could get, but when I saw that he was carving out a place different from what he was most well known for, it went even higher.

I know how hard that is. When I started [working] with Tim Burton, there was part of me that [wanted to] make more Oingo Boingo songs: use electronics, use guitar, use drums, make it more pop based. I did the opposite— full-blown orchestral scoring — which, to me, was a much harder challenge. Trent, in his own way, did the same thing. He carved out a sound for himself that’s made an identifiable imprint on film scoring.

Nine Inch Nails dominated a whole era of industrial music. There are a lot of other artists on Bigger. Messier. who are associated with a newer, post-industrial movement: Zach Hill, Machine Girl, Boy Harsher. Have you been following their work closely, or were they introduced to you more recently through this record?

I tend to surface every 10 years like a submarine. I go down in my own bubble and come up once a decade to soak up a whole bunch of new music. I was due for a total reeducation, but again, that was part of the process with Stu and Berit. Now I’ve got all these new favorite artists.

When I’m writing, I tend not to listen to anything, and, of course, I’m almost always writing. I pull out my playlists when I’m working out, and I’ve had one for years that’s filled with Tool, Neubauten, and Nine Inch Nails. That’s what gets me through it, and it became even more so when I [started getting new tattoos]. Fear Inoculum got me through all of it, which was fucking excruciating. I got obsessed with that album playing loud in my earbuds while I was suffering on the table. It took me somewhere. The songs are long developing and pull you in — the perfect thing for trying to get my head off the pain.

Let’s talk more about the visual element of the album. The covers of both Big Mess and Bigger. Messier. have an intense body horror aesthetic to them. Has horror always been the visual genre you identify with most?

It’s always been me. Body distortion is something I’ve always been fascinated with. Visuals are what started this whole thing.

My manager had been trying to get me out to Coachella for a decade, and in 2019, I finally agreed to go with her. It was the video screens that won me over. There’d been a great technology jump in the 10 years before that, since the last time I’d been to a concert — these big, high-def screens. I [realized] I could put some crazy shit up there on those screens. I loved the idea of making a musical show that had an intense visual side.

My hope was that some of it would be disturbing, and I did have the pleasure at Coachella of watching people in the front, mouths open [mimes a gasp]. My performance art and those crazy visuals were outside the usual Coachella fare — which, with major acts, tends to get pretty slick. But we were finding really creative artists and doing super low-budget stuff.

Tell me a little bit about the preparation for that. How long did it take you to get that together and what went into it?

We did a couple months of prep the first time. We were really behind, and when it was all canceled, part of us was like, “Whew, were we gonna make it in time?” But the disappointment of having all that energy canceled was intense, and that was one of the reasons Big Mess happened. I was pretty depressed. Three months of work for something that just disappears. When Coachella was coming around the second time… I go, “Wow. We’re just as behind now as we were two years ago.” Once again, I was calling everybody to jump in and finish their stuff. It was a lot of work, just like making a low budget movie. You have to call in favors and be very inventive to find ways around problems.

You’ve worked on both low-budget films and huge blockbusters. Do you find that a smaller budget can drive a whole different type of creativity?

It definitely does. My daughter is a low-budget filmmaker, and she just finished her first feature [Next Exit, in theaters this November]. I’m really proud of her, and I like hearing about all the inventive things she does: how to do this shot or get that done where there’s no time or budget.

A lot of really interesting filmmakers started out that way. The stories Sam Raimi had from Evil Dead… constructing these crazy things like the “Sam Cam” — a huge cross they tied Bruce Campbell on with a camera attached to it on wheels… You probably know by the artwork I created for Big Mess with Sarah Sitkin that I’m a big fan of David Cronenberg, [who] started out doing all this radical imagery before he started getting budgets. A lot of artists do some of their best stuff on less money.

Is there more rock music in the works?

Now that I’ve opened that door, there’s already one or two things I’ve started toying with in my head. I’ll always say, “Maybe I will, maybe I won’t.” But then, late at night, I’m hearing a thing in my head and I go, “Fuck, alright.” I definitely wanna stretch out more. That’s the goal with everything: to get out of my comfort zone [with] how I record, writing more personally as opposed to third person, which I did with Oingo Boingo.

I’ll be starting my seventh classical commission in seven years, and I’ve given up doing a film each year so I can do this orchestral work. It’s the other side of my psyche. After doing 110 films, I have to keep myself alive creatively. These classical things are so hard for me because I have no training and I don’t really know what the fuck I’m doing, but I embrace it and learn while I’m doing it. It’s hugely challenging and exhausting. Big Mess was a challenge in its own way, and now I want to push myself further.

I realize I’m at the point where I could just be a film composer and earn a good living and a lot of people would respect me for it — just cruise through until I’m done — but I’m not ready for that. I still need to bang down doors. It’s always been my highest interest: looking for doors where I have no business being and trying to smash them down, breaking into parties I’m not invited to.