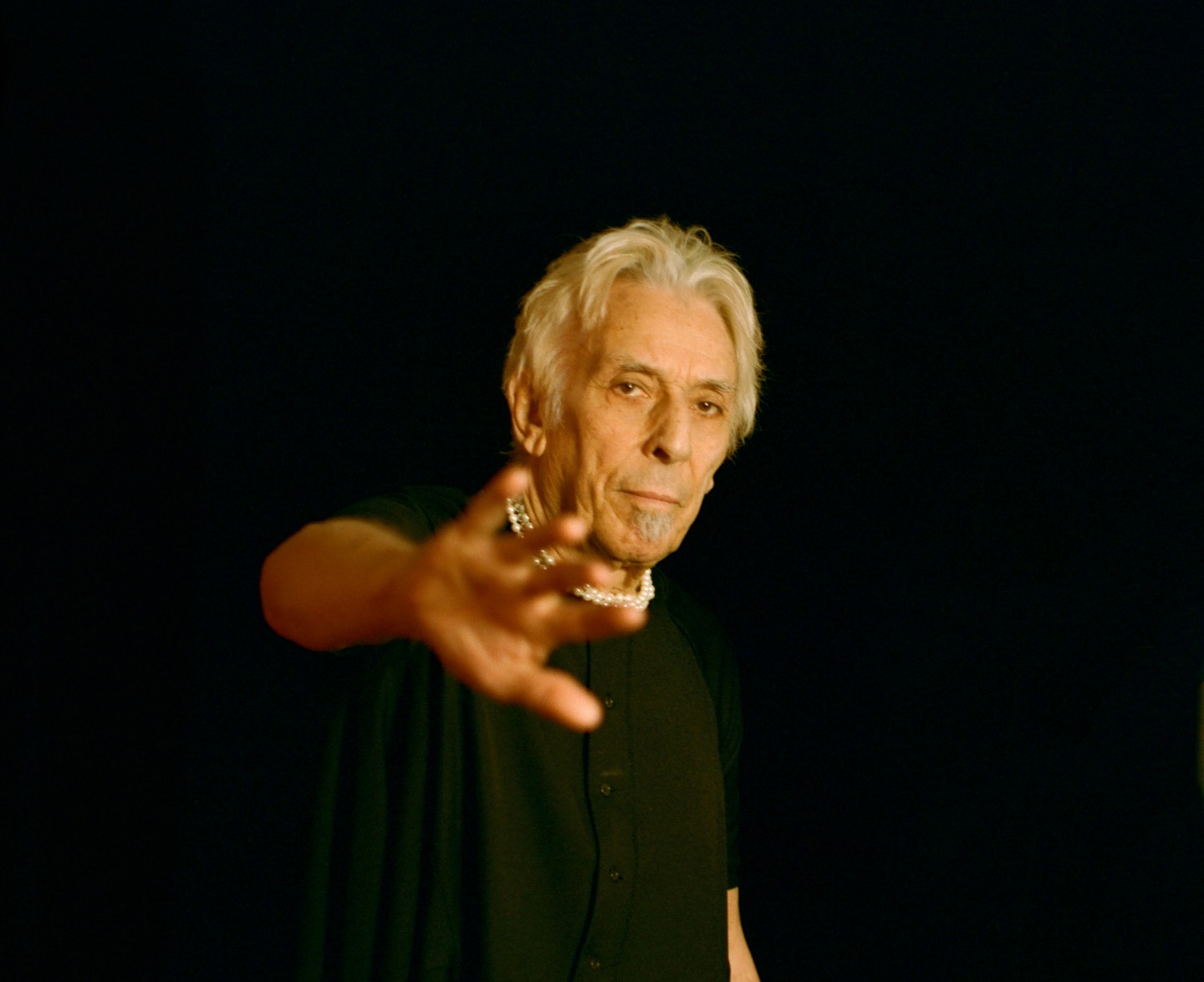

Madeline McManus

Madeline McManus

John Cale has always been a step ahead. He was post-rock while rock was still finding itself, post-punk before punk existed — constantly moving toward a distant beacon only he could see. Born and raised in the mining town in Garnant, Wales, in 1942, he took refuge in his local library as a teen, devouring music scores most professionals at the time couldn’t make sense of. His passion for the avant-garde led him across the Atlantic to the forward-thinking Tanglewood Music Center in Western Massachusetts, but his burgeoning appreciation for aggressive rock ’n’ roll alienated him from his professors there.

He found a more welcoming home in New York with Fluxus luminary La Monte Young’s Theatre of Eternal Music. Shortly after his move, in 1964, he joined forces with a young New Yorker named Lou Reed to found The Velvet Underground, where he would create drone mayhem beneath Reed’s lyrical experiments. But even the world’s most progressive rock band was intimidated by Cale’s vision, and he once again found himself too far ahead of the curve and out on his own.

Since leaving the Velvets in 1968, Cale has been in constant flux, working solo and collaboratively on everything from delicately crafted chamber pop symphonies to pulverizing dronescapes. An outspoken hip-hop fan, he’s incorporated trap drums into his own instrumentation with the same facility he’s brought to so many other innovations in sound, devouring them before recreating them in his own image.

In January, he shared MERCY, his first full-length album of original music in over a decade. It features an ensemble cast of younger acts: Laurel Halo, Actress, Weyes Blood, Sylvan Esso, Animal Collective, Fat White Family, and Tei Shi. He’s still ahead of the pulse, pulling some of modern music’s most singular freaks even further from the mainstream. With every feature, he coaxes new raw material out of each collaborator and molds it into something more powerful. At the same time, he’s subtly slowing down, drawing nearer to a place where he’ll finally be content to pass the torch.

Following MERCY’s release, I sat down with Cale for a brief but illuminating conversation about experimental music’s past and future, John Lennon’s smoking habits, and making a scene at the movies.

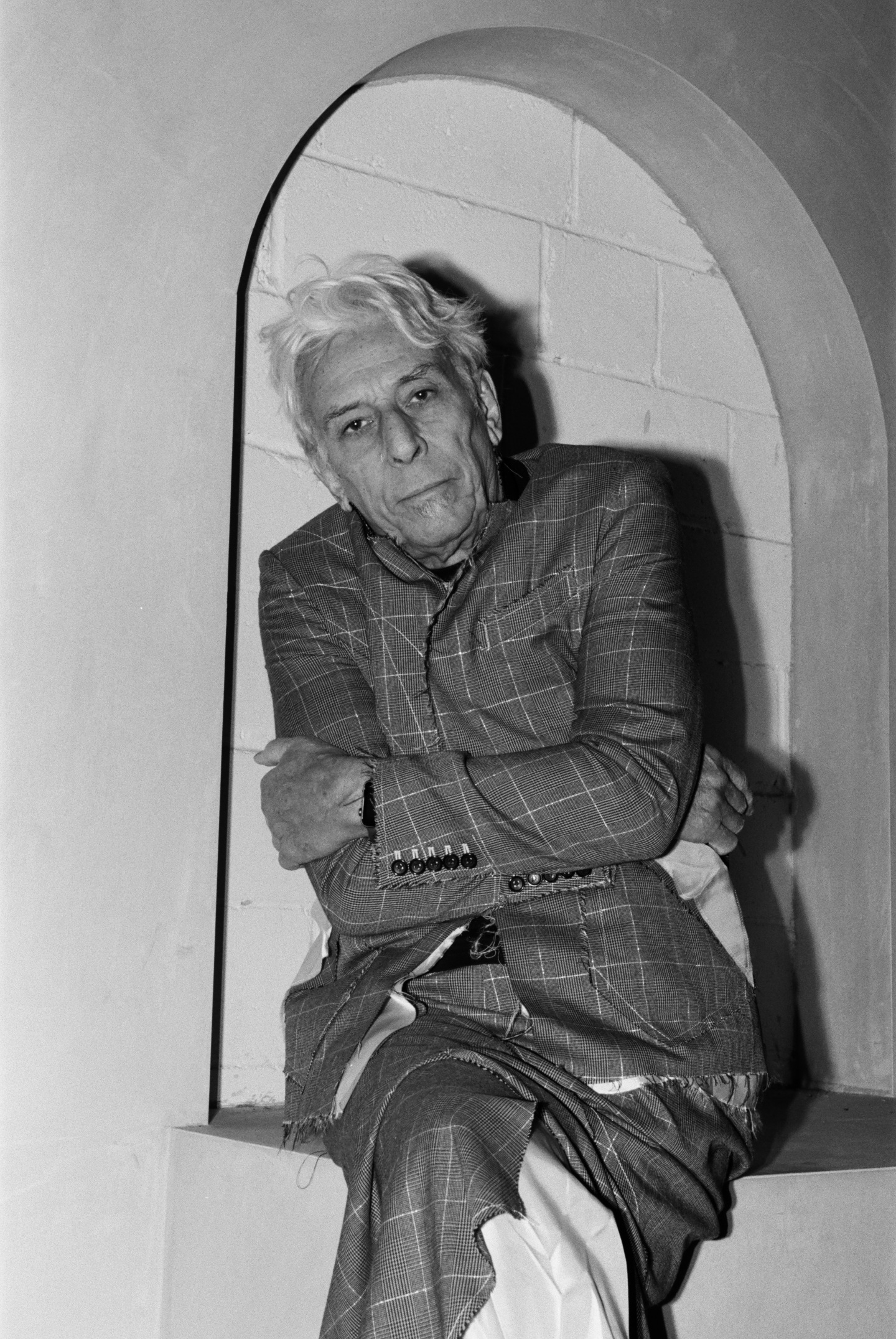

Marlene Marino

Marlene Marino

This Q&A is taken from the latest episode of The FADER Interview. To hear this week’s show in full, and to access the podcast’s archive, click here.

The FADER: Growing up in Wales, you were drawn to the bleeding edge of Western music: Berg, Webern, Stockhausen, Ligeti, Cage, et cetera. You had the ears of a much more seasoned listener. What do you think it was about your upbringing or your innate sensibility that led you immediately to music that’s such an acquired taste for everyone else?

John Cale: I was always interested in the experimental side of things. I was messing around with experiments at school, and I got more satisfaction out of understanding algorithms than what a melody meant, so I got used to that. Some people at school, they got used to it too, and they thought I was a nut job for wanting to go after Berg, Webern, and all the 12-tone masters. So I kept going, but then I said, “This is not all of it. This is not what all of it is meant to be.” Then slowly, you progress from what new music is about today versus new music in a decade. You may like what’s happening now, or you may not. You find suddenly that in about another two years, tastes have changed, so I was happy to follow it.

There’s a great story of you being jumped into the cult of rock and roll at age 15 when you went to a screening of Rock Around the Clock and it suddenly turned into a dance party. Was it a short road from there to immersing yourself fully in rock music? And how did your new listening habits inform the rest of your classical education?

It was already irritating for most of the people in my school. But it was surprising, the variety of responses. The Ladies of the Valley would come, and I would go with a friend of mine from high school. I’d go and sit through the film. What we were trying to do was to not create a stir. This is serious stuff. I mean, this is God here. Then, as I was walking out of the theater… Oh my God, there were the Ladies of the Valley. And I thought, “Oh, I’m in trouble now.” But what happened was the ladies said, “That was very, very funny.” They completely turned the tables on me.

“There was always suspicion about whether I was really seeing this thing from the right point of view. It depends on who you ask. If you talked to my music teachers, they would say, ‘Ah, forget it. He’s just wasting time.’

Once you came to the States and you went to Tanglewood, the rock that seeped into your classical playing got you into some trouble. You were deemed too out there for Tanglewood, too aggressive. And later, you were deemed too out there for the Velvet Underground — too out there for what supposedly the most out-there institutions in their respective forms.

I think you put your finger on the next album title: Too Out There

Whether you perceive them as rejections or not, did those conflicts ever lead to moments of doubt, or were you always completely confident in your artistic vision?

No, never. Not confident, no. I mean, there was always suspicion about whether I was really seeing this thing from the right point of view. It depends on who you ask. If you talked to my music teachers, they would say, “Ah, forget it. He’s just wasting time.”

Later on, I suddenly had friends in the music business, and you really developed a camaraderie with people from your local valley. It’s such a strange coincidence that years later, you’d run into them and they’d say, “Hey, how you doing, man?”

Marlene Marino

Marlene Marino

You still seem to hold a lot of reverence for the Fluxus artists who inspired you and believed in you early on.

Yeah, they were a bundle of laughs. George Maciunas was really the strongest guy. I mean, he was the one that got through to a lot of people in New York who didn’t quite understand what was going on.

Yoko brought John Lennon by to meet George Maciunas. George said, “Yoko, now, look. I know you’re gonna bring John around to visit. But get him to realize something: He’s a chain smoker, and I have asthma. I’m tied to my air filter. I can’t have my breathing interrupted or messed with.” Yoko said, “Well, what can I do?” He said, “Okay, I will charge you $100 per cigarette.” And George was there with his tank and with his breathing apparatus.

George was a stateless Lithuanian… but he had a following in the people who were building new buildings downtown in New York. He was in a strange position. He put this following up of people who understood exactly what the new designs were, but there were certain code rules: You can’t pay people this wage, because they’ve been trained to work for other people. It was an unfortunate circumstance. Because he wrote his own rules, he was very poorly treated. The fact that John was smoking was really the least of the problems.

“It came to a point where everybody was experimenting, and it was a scrum: all these composers who were not following compositional methods. Nobody could really point at what was going on.”

Which principles of Fluxus have you held with you throughout your career, and which have you left behind?

It’s a complicated question. The basis of the subject matter was no longer music. What George had done was he understood what La Monte [Young] was into, and it was very clear that there were a lot of people in New York who were treading the light fantastic, doing different styles of music and living. Stockhausen would be out there doing music with several different keys. There would be one key for one instrument, another key for another instrument. It came to a point where everybody was experimenting, and it was a scrum: all these composers who were not following compositional methods. Nobody could really point at what was going on. Nobody could say, “Well, he did that,” because if you said that, you were marking your territory, telling people, “This is what I did. And what are you doing?” It was a complex competition.

Speaking of Fluxus, the short film for “Noise of You” feels like the perfect document of intermedia. It’s not just a music video: the songs and the visuals and voiceover are all intertwined in a really interesting way. I read the LA Times interview where you called it your favorite song on the record. Am I going too far in calling it the core of the record?

No, it’s a very accurate description. It was my favorite song. It reminded me of a lot of European cities that I would visit, especially the ones behind the Iron Curtain. You’d find all these people there that were deprived of information about new music and new art. They’d say, “We agree with that. That’s how we see things developing in the art world, and this is what we want to do.” And of course, the government would come down like a ton of bricks on them, especially in Prague. There were a lot of home-grown rock ’n’ rollers in Prague, full of character.

You’re very upfront about calling “Noise of You” a love song, whereas you’ve expressed some ambivalence about writing love songs in the past. Do you think it’s the purest love song you’ve written?

It’s the most innocuous love song. It did things without telling you what it was doing, so it was very subtle, and enjoyable because of that. But it’s definitely a love song, and I have no qualms about owning up [to that].

At the end of that video, you say, “I want to be the one to hand you the future, starting now.” That could be read as a comment to all of your younger collaborators on the record.

I don’t mind that at all.

Are these the artists you think you feel most comfortable handing the future to?

Yeah, I certainly would.

There’s a note across the screen in the video that’s specifically about Weyes Blood. It says, “Her classical training reminds me of my blending of the two worlds.” Can you expand on that? Do you see her in particular as a kindred spirit?

Well, she’s very good at preserving both of them, and they’re both well-fed on both sides of the artistic spectrum. I appreciate that.

The collaboration between you two, “Story of Blood,” is another show-stopper. I love that you’re rarely directly harmonizing with her; it’s more like you’re orbiting each other. Is that the effect that you were going for?

I wasn’t going for it; it just happened. Some of the best things happen by accident.

A lot has been made of your appreciation of hip-hop at large and trap in particular. I think “Story of Blood” is the song on the record where you best-integrated trap elements, particularly the machine gun hi-hat. Were there any producers, in particular, who inspired you on this record?

I’m always listening to Kendrick Lamar. A lot of the new artists have really stuck to their guns. I mean, I love Snoop and Dre. Earl Sweatshirt has a strange and wonderful atmosphere about him.

I know you had intense classical viola training, but I’ve never heard much about your vocal training, and I think your voice stands out as somewhat of a constant in your very fluctuating career.

Well, it’s a fluctuating vocal. It’s shifting the furniture on the Titanic, because I always get bored with musical developments real easy. But I also get a kick out of listening to all the new stuff that’s going on. They’re always giving me a kick in the butt — not that I speak to them about it, but I draw from them what I appreciate.

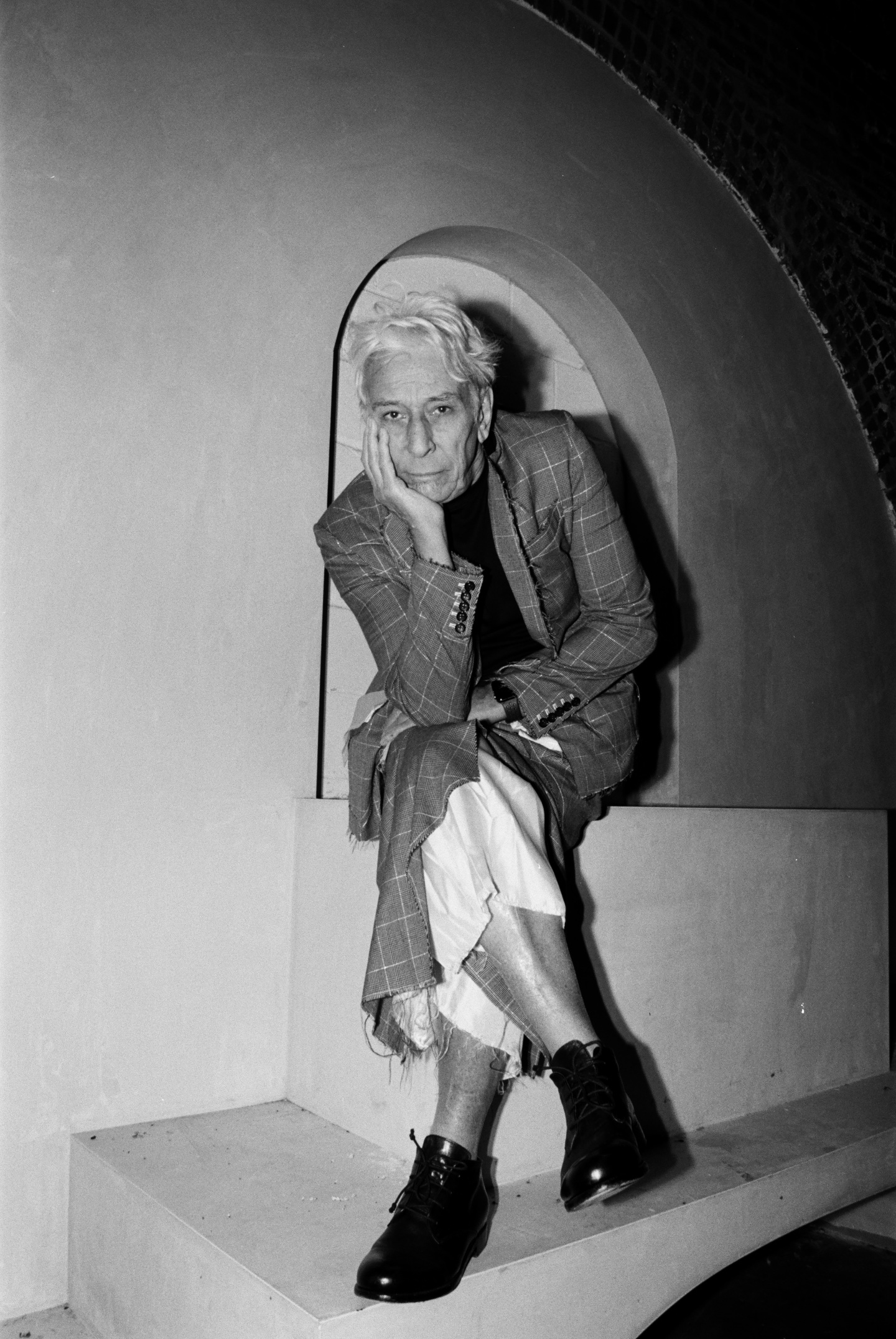

Marlene Marino

Marlene Marino

You’ve got one of those voices I think is recognizable across form. While you’re vastly different artists from him, I sometimes think of your career in parallel with that of Scott Walker, who’s another—

It’s very funny you should say that, because a lot of people in England kind of said that.

I’ve never heard you talk about him, so I’m curious whether you were inspired by him, whether he was inspired by you.

It was one of those shady partnerships… Not partnership, that’s the wrong word. We didn’t know each other well enough to really have a partnership. But it happened in London, when I was on island. I suddenly found myself listening to people talking about Scott Walker. They were noticing stuff about his style of production. Because I left London around the time he popped up, I really didn’t get too much of an education in Scott’s direction. I certainly went looking for it, but I couldn’t put my finger on it. That’s why it was such a strange occurrence to have a conversation about someone I never met.

Returning to the Fluxus theory of art as a point on a continuum rather than a destination or a goal to be reached, do you look back on any of your projects as one opus? Or is the next project, the one you’re working toward, always the most representative of the essence of John Cale?

The last one.