Emily Keegin

Emily Keegin

Instead of looking back, The FADER has typically chosen to look forward, focusing on the young creatives who nudge culture ahead. But now, on the occasion of our 100th issue, it feels like the right time for a little history, if for no other reason than to call attention to the great minds, great music, and great luck that has carried The FADER through 16 years in an industry that changes at lightning speed. Here, members of the FADER family past and present look back on their time at the magazine and explain how we made it to this milestone.

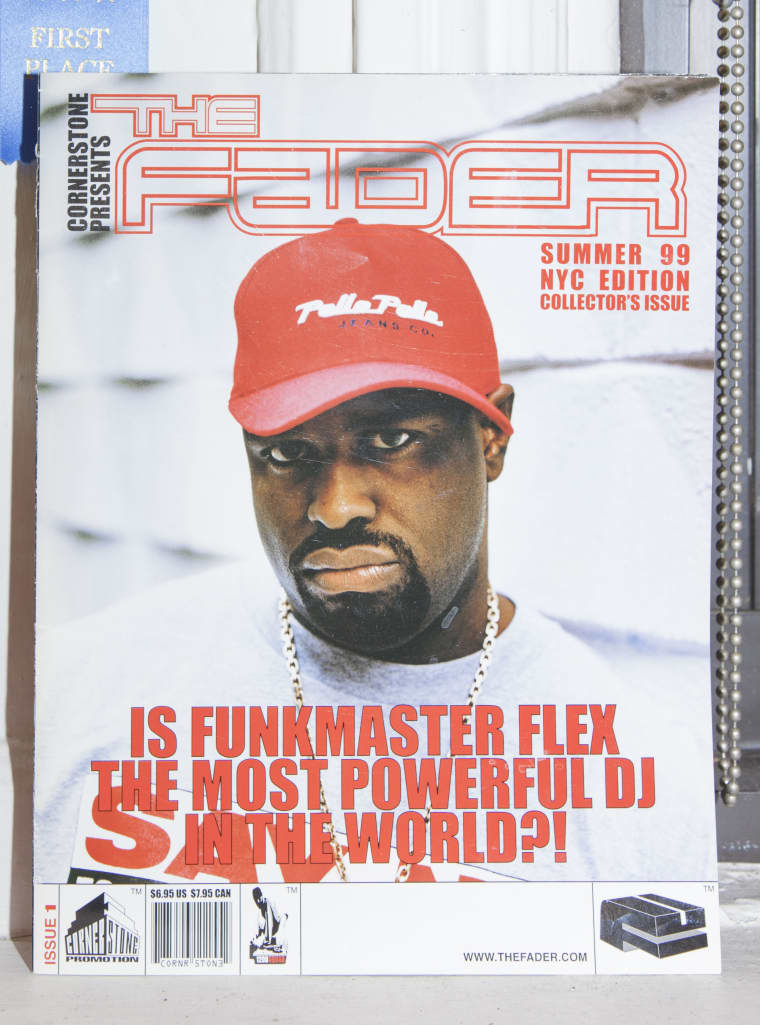

The FADER was founded in 1999 by two childhood friends, Rob Stone and Jon Cohen, as an outgrowth of their music marketing agency, Cornerstone.

JON COHEN (co-founder and co-CEO): The FADER was an idea that Lee Harrison, who was heading up a lot of the creative on the Cornerstone side of the company, had been kicking around with Rob. How do we show the DJ community more about the projects we are working on? It was initially intended to really expose all the great music we were involved with, particularly the hip-hop side—more of a trade industry pamphlet.

ERIC DUCKER (former senior editor): FADER was conceived of more as a magazine that appealed to DJs. There would be pages where DJs around the country would make their top three record picks.

JONATHAN MANNION (photographer): The first issue was Funkmaster Flex. The team was rushed and pressed, and if they didn’t make deadline, they weren’t going to have the magazine. I literally shot the cover on the side of the building at my lab on 30th and Lexington. I was throwing rolls up to my lab on the second floor to have it back by the evening to be able to go to press.

ROB STONE (co-founder and co-CEO): We didn’t have money to pay Jonathan when we started. He did the first four covers on a handshake. I think we bought him a computer because he had mentioned that he needed a new computer, so we just got him whatever was the best Mac out there. But it wasn’t really about the money for him. It was the freedom that other publications weren’t giving people, we would give.

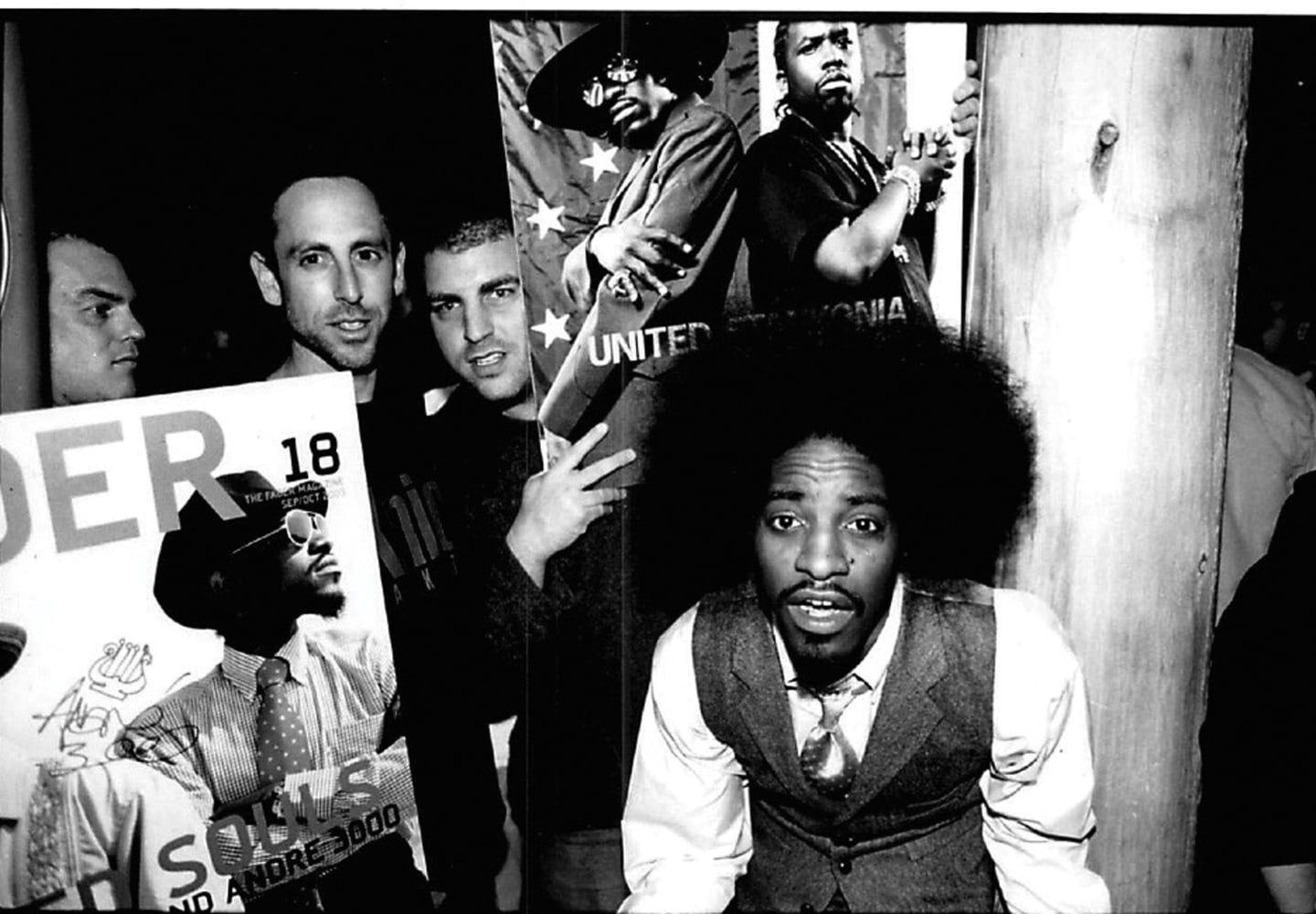

Jon Cohen, Rob Stone, and Outkast’s André 3000, in 2004.

Jon Cohen, Rob Stone, and Outkast’s André 3000, in 2004.

ERIC DUCKER: As the magazine took on a life of its own, Lee decided that this could be a real magazine, not just a DJ magazine. Lee didn’t know how to edit or write, so he brought on Eddie, who had that history.

EDDIE BRANNAN (former creative and editorial director): At the time, there was literally black music magazines, and there was white music magazines. There was Spin, Rolling Stone, and then there was the Source, XXL, and Vibe. But we weren’t listening to music in that way.

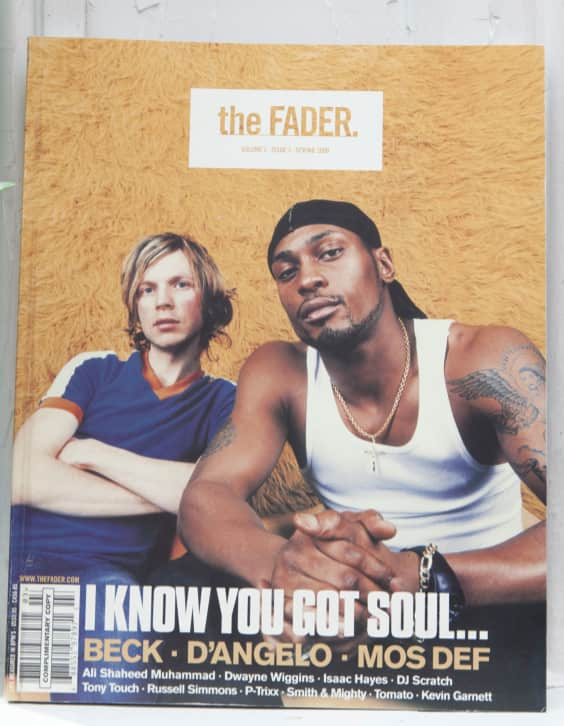

JON COHEN: If you were to say where FADER had its real launching point, I would say it was issue three, where we brought Beck and D’Angelo together and we started meeting some real writers and real people with experience. The artists came casual—there was not a high level of stylists, and there weren’t publicists around controlling the moment. They sat down and had a conversation, and Beck had rolled a joint for the occasion. It really set the tone for what FADER has become.

EDDIE BRANNAN: We would take writers who were more typically associated with one genre, then have them write about music or stuff from another genre. We would do the same with photographers. We always tried to pull the rug out from under people’s feet a little bit, get them out of their comfort zone.

JON CARAMANICA (writer, New York Times pop critic): I don’t want to say D’Angelo didn’t know who Beck was, but I don’t get the sense that he was as amped to talk to Beck as Beck was to talk to D’Angelo. A striking thing happens throughout that interview, which is when they start to get down to first principles—Why do you do what you do, what are your influences?—all of a sudden they are starting to talk in the same language. Over the course of the hour, you start to see two people who realize they actually had things to talk about.

JON COHEN: We started doing two covers because it gave us prime real estate to make a very big statement on the way that genres were starting to influence each other.

ANDY COHN (president and publisher): A lot of music magazines were focused on growing their circulation, charging more for advertising, which meant they were very limited in the artists they could put on the cover and the type of artists that they would cover in the magazine.

“The idea that all those people should live in the same playlist, CD collection, iPod, was novel in the early 2000s. It shouldn’t have been, but it was.”—Jon Caramanica, New York Times pop critic

ROB STONE: We were never about revenue from ads. This was going to be about us documenting culture. That’s why we put an artist on the back cover. We didn’t care about selling the back page.

KNOX ROBINSON (former editor-in-chief): It’s kind of too obvious, too easy, to think of FADER’s two covers as the twin poles of hip-hop culture and indie rock. You could have a black cover and a white cover, but what would Jimi Hendrix say about that? At the time, Outkast was really rocked-the-fuck-out, and The Strokes were kind of the flyest dudes in the city, more than rappers. Brothers were wearing leathers and digging indie, and there were electric guitar solos on hip-hop records. It was an incredible watershed moment for the culture.

I wanted a magazine for black kids to feel okay about being into rock and white kids to feel okay about being into hip-hop. I don’t think every brother in hip-hop had to be out there FUBU’d down and baggy to the fullest. There’s a lot of ways to celebrate black male style, and we were trying to portray that whole range, that whole mix that’s the rich heritage and legacy of black American culture. I didn’t even really want to make it that big of a deal; I wanted to demystify it, actually.

JON CARAMANICA: The idea that all those people should live in the same playlist, CD collection, iPod, was novel in the early 2000s. It shouldn’t have been, but it was. You have to understand in the ’90s people were fighting culture wars. This is sort of the beginning of the shift away from that. The idea that all of those people could live in the same house, and, quietly, behind closed doors, actually had a lot to say to each other. That was radical. And The FADER was at the center of that particular conversation before any other music magazine showed up.

ERIC DUCKER: Eddie and Knox were really into the idea of new journalism, which had been a movement in the ’60s and ’70s made famous by people like Tom Wolfe and Joan Didion and Hunter S. Thompson. Some people hated that we did that; some people thought it was self-obsessed, and distracting from the subjects. But it was this idea that we’ve got to do something different. Let’s not be boring. Let’s try to have fun.

EDDIE BRANNAN: The old FADER office was central with corridors all the way round it. That’s why it was, and still is, called the fishbowl. That was our office, and it was messy. There was stuff all over the place. There was usually music playing at maximum volume. We would be coming in the morning hungover, sometimes straight to work from wherever the hell we’d been. Knox and I got in a ridiculous car accident one night. He had to take some time off. I was in the office the next morning with whiplash in my neck. Lee Harrison was freaked out because we’d both nearly killed ourselves.

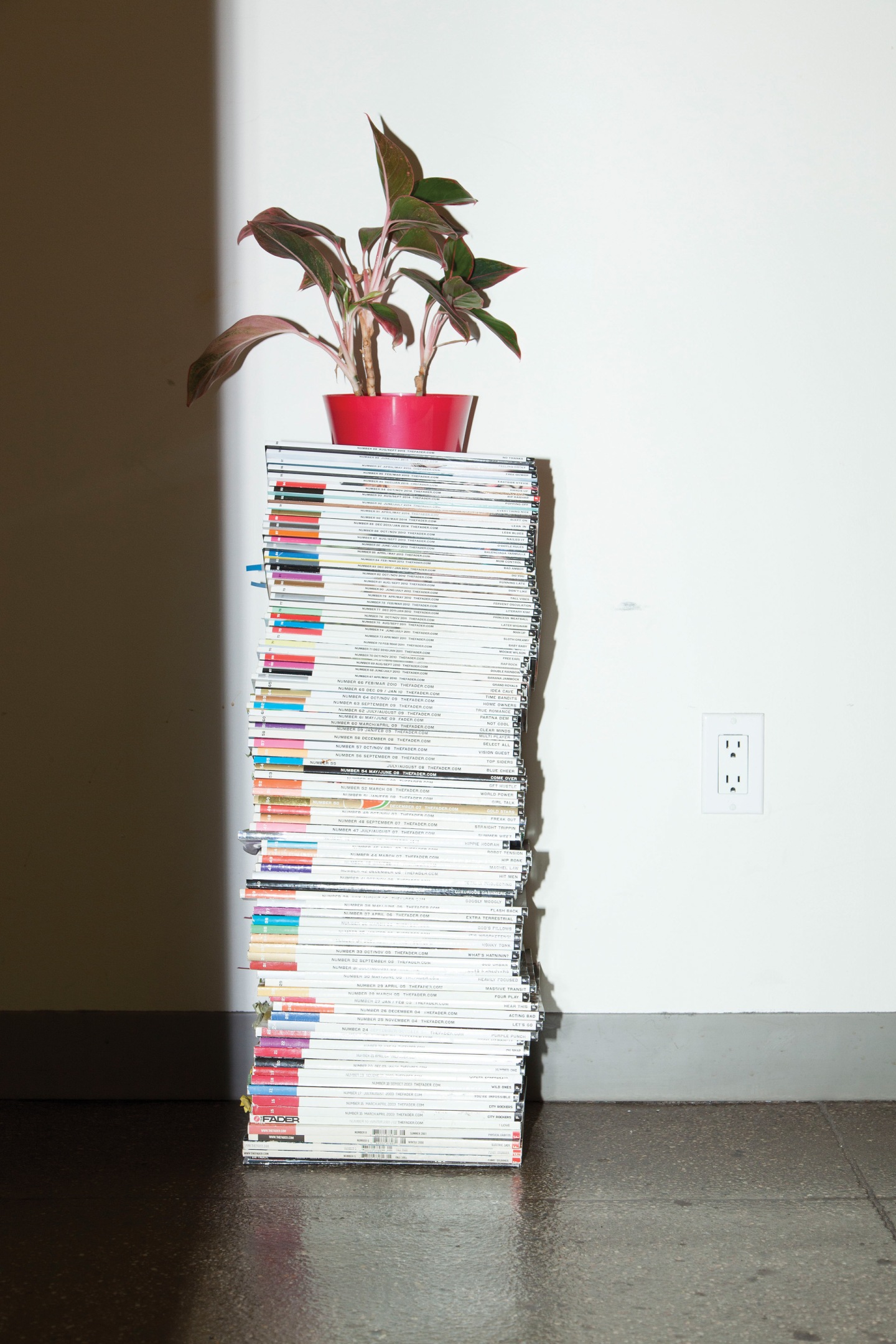

The FADER fishbowl in 2007.

The FADER fishbowl in 2007.

“People forget that there is nothing they have done that wasn’t the result of a lot of other people’s hard work. I never thought of the magazine as mine. I thought of it as ours.”—Alex Wagner, former FADER editor-in-chief.

ANOMA WHITAKER (former fashion editor): I was living with Eddie Brannan. Knox was always falling asleep on my sofa and chair. Simonez [Wolf, a former fashion editor] was always around or scattered or late or lost a garment bag. It was a non-stop group of people. It never felt like we weren’t talking about all of it—if it wasn’t in the office, it was downstairs in the bar, or it was in our apartment on Union Street in Gowanus. On Fridays, you’d go to El Sombrero, and you’d get frozen margaritas in the milkshake cups and then do editorial meetings and end up at the basketball court on Delancey, twisted on really cheap tequila, still talking.

ERIC DUCKER: Jeff Staple was doing the design. His photo editor at the time was Angelo, who is now at Supreme. We’d scan the photos, bag ’em up, and send the actual photos to the printer in Canada with the discs, and then someone would have to drive up to the printing plant and check the color proofs. I think Lee and Anthony would do that. To some rural place in Canada.

WILL WELCH (former deputy editor): A classic, definitive FADER cover to me was Cam’ron and M.I.A. Cam’ron had had this sort of rickety career, but had established this crazy momentum based around this whole mixtape culture that was happening in Harlem. M.I.A. was this girl from London who Diplo had connected with, and who Knox Robinson had found out about, sort of through Diplo. She was a complete unknown entity. You could have called them shots in the dark.

KNOX ROBINSON: The first time I heard Kanye West, he was in Rob Stone’s office freestyling with the backpack on. The kid wanted to be recognized as an artist and seen as a lyricist. The passion that he was putting on right there for the hard sale—it was crazy to watch.

WILL WELCH: He was just coming from a totally different perspective. At the time, 50 Cent was dominating hip-hop. It was like 50 Cent and G-Unit. But Kanye was talking about going to college.

When he came up to the office to do the interview, Knox and I decided we would interview him together. I suggested some restaurant in the area, and Kanye was like, “No, I just saw a Boston Market. Let’s go to the Boston Market.” There was a Boston Market down the street, so we walked over there and sat down and got food and talked for a long time. Kanye had a Roc chain on, and there was some kid that was like, “Kanye!” and threw up the Roc symbol. Kanye was so stoked that somebody had recognized him, because at the time you had to be a real rap nerd to recognize the guy who did the sped-up soul samples on The Blueprint. He was like, “Oh yeah, I got recognized on the street. Sweet.” He didn’t say that, but you could tell he was stoked.

In true Kanye fashion, his publicist, Gabe Tesoriero, called me two weeks after the interview and was like, “Kanye wants to talk to you. He feels like you’re not done with the interview.” I was like, “Between me and you, the magazine has shipped. It’s at the printer.” He was like, “Man, it doesn’t matter, you got to have another conversation with the guy.” Nothing is ever done.

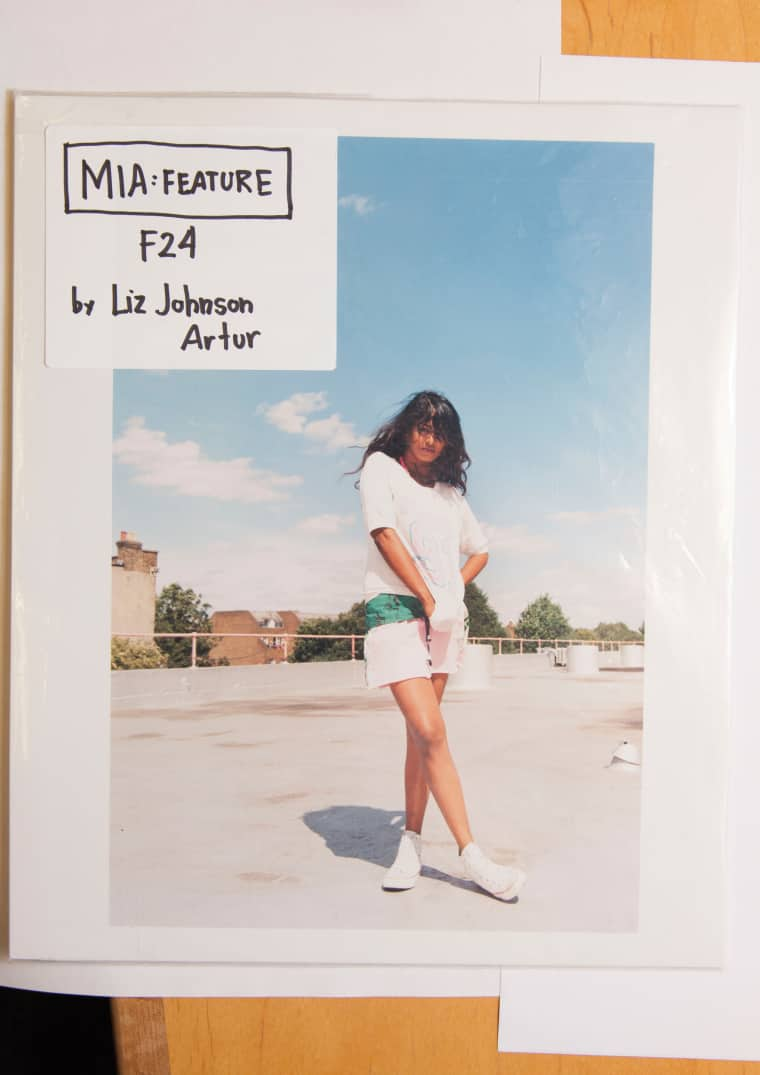

Photo proof from M.I.A.’s first FADER shoot.

Liz Johnson-Artur

Photo proof from M.I.A.’s first FADER shoot.

Liz Johnson-Artur

Emily Keegin

Emily Keegin

By the mid-2000s, FADER was finding its footing and an identity defined by documentary photography.

PHIL BICKER (former creative director): I came from The Face, where I stuck Kate Moss on the cover—a 15-year-old girl who represented what I felt was the demographic of the magazine. She wasn’t a supermodel—not one of the six-foot supermodels. So you know that kind of thought process was applied to FADER, in terms of having content that fits the demographic of the magazine.

WILL WELCH: Phil was like, “We’re not doing any more fucking posing rappers or any sad indie rockers against a wall. It’s just not going to happen anymore.” At the time, that was just what a photo shoot was in the music industry. We were calling people and insisting on coming to their houses. That was just really dicey on so many levels, but Phil, he just wouldn’t relent on that. We’d be like, “Man, I don’t know. This guy’s saying he doesn’t really have a house. He moves between places. He’s in his friend’s car or on somebody’s couch.” He’d be like, “Perfect, we want to go to his friend’s couch.”

PHIL BICKER: The point and purpose was photography first. FADER photos were documentary in spirit, but not documentary in fact. I think that the idea of text and image telling you the same story is something which the mainstream has dedicated itself to for so long, you know? Photos illustrate text. At FADER, photos didn’t illustrate text. Photos ran to tell you something that the text maybe couldn’t. If there was a reason to explain what was going on somehow in the context of what happened, that was fine. But there was no reason for the two things to be repetitive. They could weave in and out of each other.

ALEX WAGNER (former editor-in-chief): When I came on, it was like absolute, unmitigated, disastrous chaos. We would be there until like 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning during close. Someone would break out, like, bourbon. The computer server—which was nicknamed Buttercup—would shut down, and we would lose features. And we would play that song, Why do you build me up/ Buttercup, baby, just to let me down? It was totally, totally awful and spectacular in its chaos.

WILL WELCH: There was, like, four or five of us sitting in a really sweaty room talking about music we loved, talking about ideas, talking about photography and design and writing. It was just not a clock in and clock out job. You were there all the time. There was a shit load of fighting about stuff. A lot of screaming and sweating and cussing.

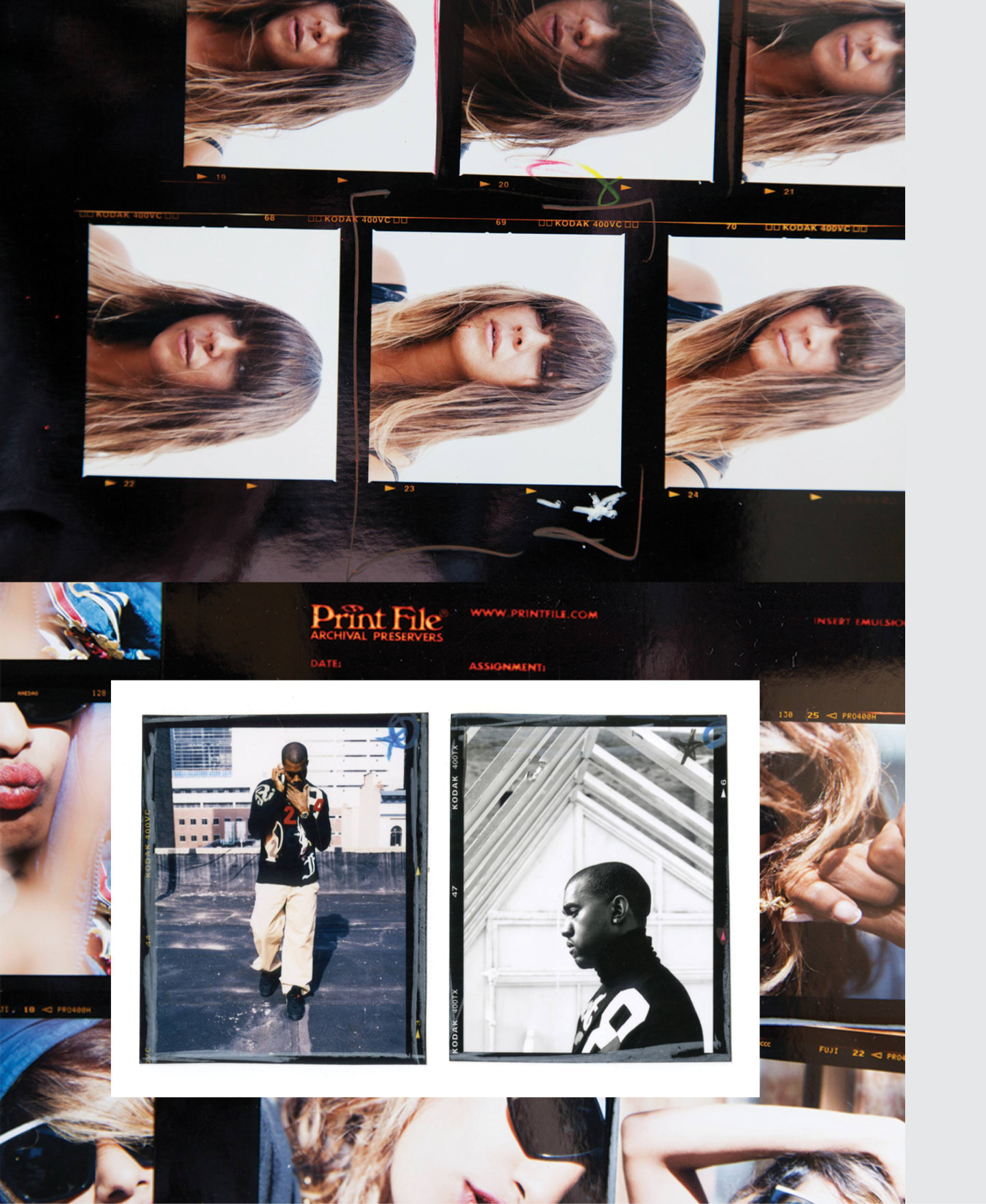

Cat Power and M.I.A. contact sheets by Jason Nocito. Kanye West contact sheet by Jonathan Mannion.

Cat Power and M.I.A. contact sheets by Jason Nocito. Kanye West contact sheet by Jonathan Mannion.

“There were no YouTubes, there were no embeds. We would get mixtapes from the African dude that had a stall on 14th Street and bring them back and play them really loud and then write about it.”—Nick Barat, former FADER associate editor.

ALEX WAGNER: First we get our egg and cheese sandwiches, then at like 4 o’clock we’d have lunch, and then at like 7 o’clock we start thinking about maybe leaving the office and then we all go to a show. I remember my boyfriend at the time was just like, “We no longer exist in the world because you are at the office all the time.” It was like a treehouse, this hideaway. And then a magazine happened to pop out of it every few weeks.

ERIC DUCKER: I think Alex Wagner made things a lot more professional. Even the fights felt grown up.

ALEX WAGNER: I am of the mind that fighting is a good thing. I just think there’s something really reassuring and honest about a place where you could just scream at people. The number of times Will would just leave my office and slam the door and it would shake the hallway. Phil punched a hole in the wall once. He was a pain in the ass in the beginning. I remember he came in and laid out all of these cover shots on the floor and he said, “I am up here, and you’re down here.” At first, we were like, “You’re a dick.” And then it became, “Phil’s incredible, and has so much integrity, and his taste is impeccable.”

ERIC DUCKER: Making sure Phil had a production coordinator, a photo editor—Alex fought to get the staff to a somewhat reasonable size. There’s more people to just do the work. The magazine was growing in size—you just had to have more people.

DOROTHY HONG (former photo coordinator): A FADER shoot would always be really quick. I learned how to shoot quickly. Every other magazine, there would be various setups, clothing changes, but at FADER, there was no wardrobe, no hair and makeup. It was very much, go to their apartment, their studio, wherever they work and shoot them there, with just

natural light.

PHIL BICKER: I would do so much research. I’d say, “Okay, right, we’re doing Kanye. What’s the research basis for Kanye?” Not two or three pictures—hundreds of pictures. I would send those photos to the photographer. It was like, “Here’s a picture of Stevie Wonder, because I kind of think it relates to something about Kanye.”

JASON NOCITO (photographer): You would just show up and shoot people. I went down to hang out with Cat Power at her house and slept on her floor. We ended up staying up all night drinking—I had never drunk whiskey that way my entire life—and the bottle was shrinking, and I was basically blacking out. I was shooting photos for hours with no film in the camera. Didn’t notice. Then, we woke up the next day and we took these beautiful photos completely hungover—that was the way things would roll.

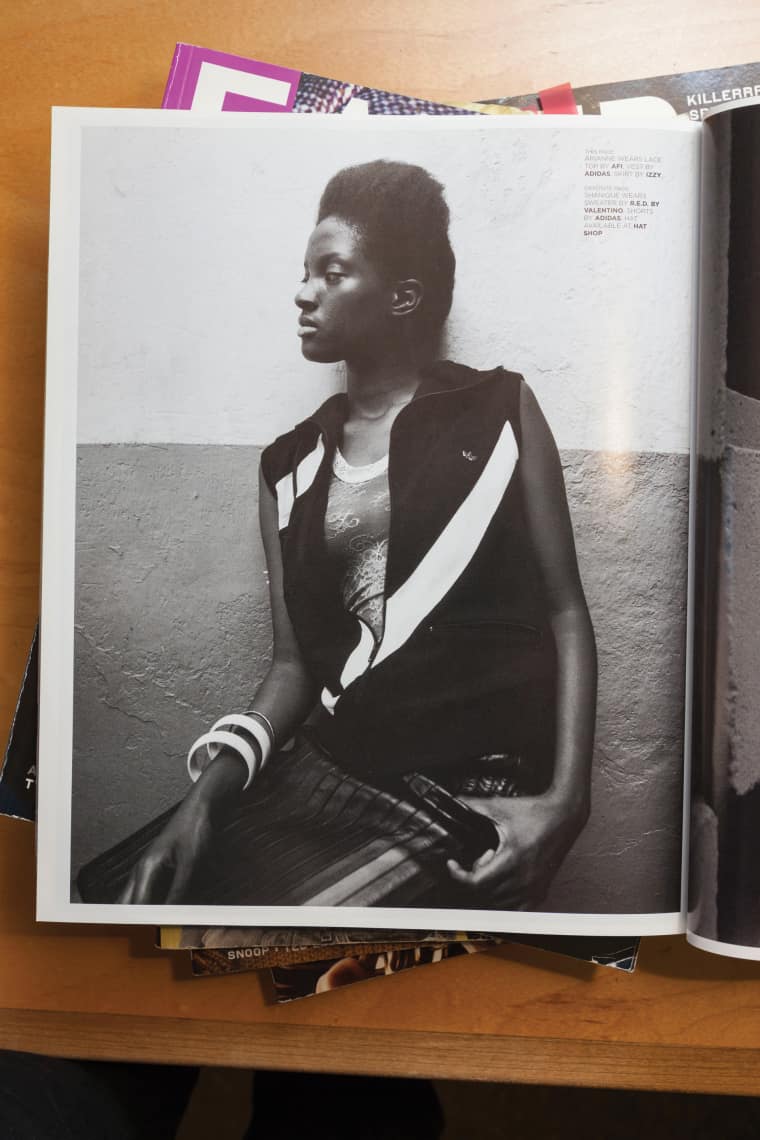

Alongside music, style was always an integral part of The FADER, with a focus on emerging designers and fashion editorials shot all over the world.

PHIL BICKER: The idea with FADER fashion is that it should be much more related to the photography, and much less related to the idea of being fashion for fashion’s sake. Not so Vogue. The idea was that people should look like they’re wearing their clothes. Andrew Dosunmu, a photographer who I’d worked with a long way back, introduced me to this young guy he was working with called Mobolaji. And blessings to me and thanks to Andrew, I inherited Mobolaji at the outset, and that was a great relationship. I thought FADER budgets weren’t too great, but Mobolaji has had a good run on it, traveling the world.

MOBOLAJI DAWODU (style editor-at-large): I started when I was 23. I got a call, “Do you have a passport?” I said yes, but then I couldn’t find my passport, so I got a new one in two days, and Phil Bicker sent me off to Jamaica for the first fashion story that I ever did, issue 24, and I ended up staying three weeks. Since then, I’ve been to India, I’ve been to South Africa, I’ve been to Mozambique, I’ve been to Thailand, I’ve been to every continent except Australia and Antarctica.

DOROTHY HONG: Mobolaji is unlike any other stylist that I work with. Other stylists are a little more organized, maybe. With him, everything will be wrinkled or something. He won’t bring a steamer with him. He won’t bring all the right sizes, and then we’ll just mix and match.

ERIN HANSEN (former fashion assistant): The style editor Chioma Nnadi, Mobolaji, and I were forever brainstorming resourceful ways to make something beautiful from nothing.

MOBOLAJI DAWODU: We’re loaned clothes out from showrooms, and I take them packed in two big duffle bags—I call them body bags—and we travel. I do street-casting, so it could be someone that I meet on a plane, it could be someone that I bump into on the street. I just basically find people that I feel have a vibe, someone that stands out amongst the crowd, somebody that has something—an individual style, something very specific to themselves. You let people wear their own clothes if they choose to. Like, you don’t force a hat because you want to get a hat credit in.

Andrew Dosunmu

Andrew Dosunmu

Mobolaji Dawodu

Mobolaji Dawodu

The FADER’s reputation grew in the mid-2000s, in part owing to prescient covers and enthusiastic, oddball tastemaking.

ALEX WAGNER: I think part of the thing that has granted The FADER unprecedented access to certain people is the fact that very early on there was a decision made not to write nasty record reviews. And that distinguished it from like every music magazine ever. It was like, “Oh we are not going to have fun shitting all over your record that you worked really hard on. We’re just gonna actually put music in the magazine that we like.”

SAM HOCKLEY-SMITH (former senior editor): I remember coming in as an intern, and I got assigned to write a small review of some compilation. I was like, “I wanna be the cool critic guy.” It wasn’t a negative thing, but I was a little extreme on the negative side. I remember at the time Will Welch was like, “Hey, I get what you’re saying, but did you like this at all? Because if not, we just shouldn’t run it. Let’s run something that you’re enthusiastic about.” It was such a nice culture to be a part of.

PETER MACIA (former editor-in-chief): What’s always cool about FADER being staffed by young inexperienced writers is that it fits the subject matter. We’ve never written about stuff like the New York Times does. We don’t want it to be the record of something. It’s, “I’m a young person, I’m super excited, and I’m going to write exactly how I basically talk.”

ALEX WAGNER: When we were hiring people, we very consciously didn’t want to hire people that seemed like they would work at a music magazine—or necessarily a magazine. I mean, that’s why we would hire DJs.

NICK BARAT (former associate editor): At the time, there were still lots of magazines, so you could be the sort of person who has a college degree, but you’re doing little blurbs about Dave Matthews Band in Blender. We were the antithesis of that. If you have wack sneakers, I don’t care about your opinion on music. We were out at clubs. It wasn’t a time where everything was discoverable on the internet. Even stuff we take for granted—there were no YouTubes, no embeds. We would get mixtapes from the African dude that had a stall on 14th Street and bring them back and play them really loud and then write about it. If you wanted to write about something, you had to dig around and you had to find the weird cell phone number of the weird friend who is going to put you in touch with David Banner because David Banner’s label publicist is not fucking with him at the moment.

Sometimes there were just brick covers—amazing stories, awesome pieces of reportage and art and phenomenal photos, but in terms of what’s supposed to go on a magazine cover, like, total bricks. I remember the Maceo cover in Atlanta. In retrospect you look back and the same time that Maceo’s records were coming out, there were other records by his labelmate, this guy named Gucci Mane. It could’ve just as easily been Gucci Mane on the cover instead, but that’s the roll of the dice. They sent Diplo down to interview Maceo—Diplo is actually, on the low, a really interesting writer and is able to just kind of finagle his way into situations like nobody else—and they sent Jonathan Mannion down to take photos, and it’s this amazing snapshot of strip-club rap and bando rap before there was a name for it. But Maceo didn’t do anything at all with his career. It was a fail, but it was a dope fail.

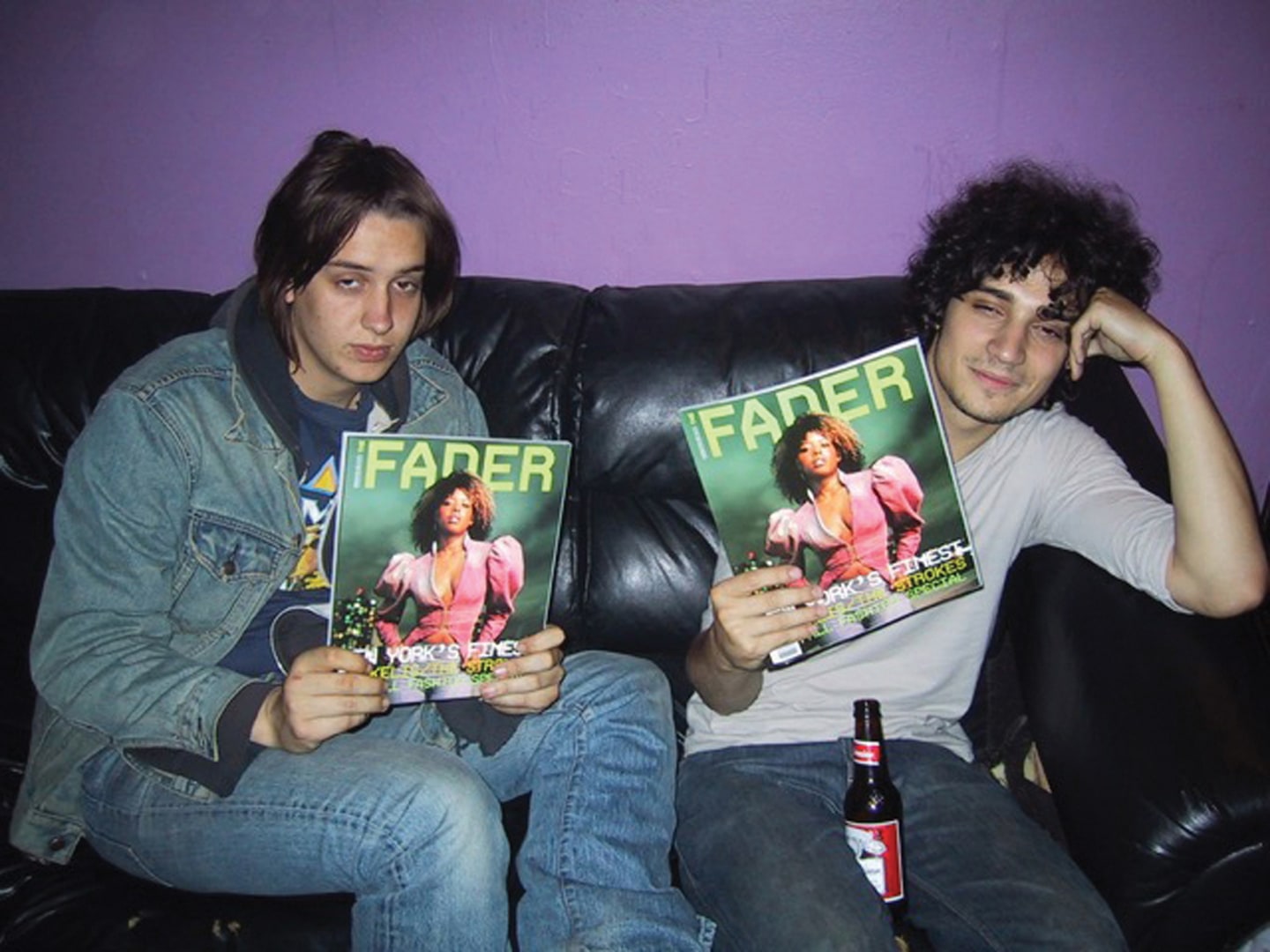

The Strokes at The FADER 9 issue release party.

The Strokes at The FADER 9 issue release party.

As the magazine developed, The FADER started showcasing artists and its own brand with increasingly large events.

JON COHEN: The FORT was really born from a party we had after the 2002 VMAs, where The Strokes played in a very small environment. We called it Lowlife, and it was almost an anti-VMAs party. How do we create an event on that same night to appeal to everyone that wanted to be a part of what was going on in downtown New York but couldn’t really care less about what Britney Spears was going to do? The block was shut down, and we had literally 5 to 6,000 people trying to get into this 2,500-capacity space, and it went on until 6 in the morning. That was the moment when FADER went from the pages to becoming something tangible.

KAI REGAN (photographer): Two thousand people in a party drinking with three bathrooms—I saw this dude Gavin McInnes drinking a beer while at the bar getting another drink, pissing in a trash can. And then he looked at me and winked.

JON COHEN: André and Big Boi were there, Jack and Meg from the White Stripes, Brittany Murphy randomly was there, all of Van Halen was there. It was just this random mix of worlds colliding and it was a chance for everyone to truly realize that FADER has defined its own culture. The Strokes—this is the height of The Strokes’ success—were out of their mind drunk. But they played an incredible show.

ROB STONE: The next morning I got a phone call from Puff. I had invited him to the party, and he was just like “Yo, next time you got a party, I need a back door. I need a side entrance. You can’t expect me to come in the front.” He’s like, “The block was closed down!” He was annoyed with me that he didn’t get into a party after I probably haven’t gotten into 10 Bad Boy parties.

ANDY COHN: Sticking to our original mission statement and applying it to events—it meant that people saw the logo, and it meant something to them. We were able to translate that outside of print, to let people see it in the real world.

“It was like learning to drive while you were in the car by yourself going really fast, which is real terrifying and also very thrilling at the same time.”—Matthew Schnipper, former FADER editor-in-chief.

ROBERT ENGLISH (EVP, music and talent): We decided to test out Austin during SXSW in 2003. I think we called it the Warehouse. None of us had experience booking talent. We didn’t have a stage, unless you count a large area rug on a cold, unfinished concrete floor. I wasn’t sure if bands would want to play if they weren’t being paid, but there was immediate interest.

ANOMA WHITAKER: Damian [Bulluck, former director of marketing] made sure the people who came to a FADER event thought it was their event. During CMJ, FADER had washing machines, because all of the rockers were grimey. We’d let them clean their clothes and drink alcohol. It seemed silly, but if you’re a musician that really meant something.

KAELA LAROSA (former senior marketing and events director): With SXSW in Austin, I was very lucky to be there for a transition through these different size spaces, going from a couple-hundred-person capacity to 500- or 600-person capacity to the big FORT space.

ROBYN BASKIN (VP, marketing and events): I often think of FORT as the living, breathing embodiment of our magazine. It’s everything FADER represents come to life. The audience, the music, the style.

ROB STONE: The FORT is just as important to us as the magazine.

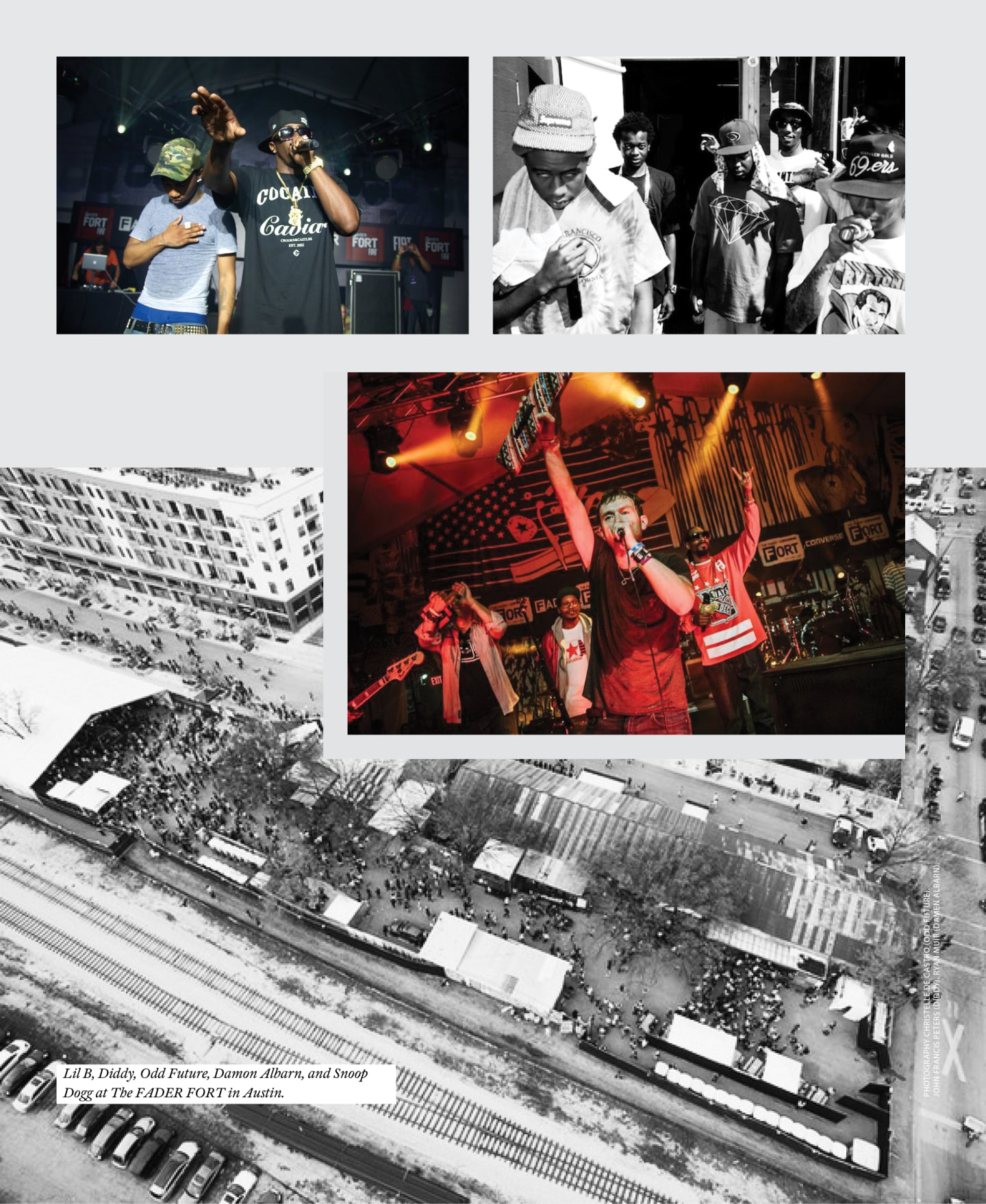

MATTHEW SCHNIPPER (former editor-in-chief): I think one of the things that The FORT wanted to say was, “Anything can belong anywhere.” That was exciting, that anything could be a part of anything else. If you build it, they will come. Throw this shit together and say this is what makes FADER. We got Lil B and Puffy to perform together, which makes no sense but also makes perfect sense.

Rob Stone, Kanye West, and Jon Cohen at The FADER FORT in 2009.

Dorothy Hong

Rob Stone, Kanye West, and Jon Cohen at The FADER FORT in 2009.

Dorothy Hong

The FADER began before music blogs really existed, but by around 2006, it was pretty clear that the internet would change both publishing and music.

NICK BARAT: I feel like in the early days of the website, publicists and label people didn’t know what was at their disposal. They didn’t know the power and the reach, and that was when they were still shutting down, like, Zshares and stuff. It was really this backwards approach, so that led our web content to be a little bit more improvisational.

ANTHONY HOLLAND (chief operating officer): We had started posting magazine content online, but when we hired Nick in 2005 is when we launched the real website and blog. Seeing Nick and knowing that the future was rapid blogging, and that was a new form of emerging journalism that was different than print—that’s key. We took traditional high quality journalism and brought it to the web, and we had that viewpoint even when we were doing simple blogging stuff.

JULIANNE ESCOBEDO SHEPHERD (former executive editor): We didn’t care if a post was gonna get a million hits. You could just write blog posts. It was stream of consciousness. I was interested in Lauren Flax’s music, and one day she was like, “Hey, I just did this song with this girl Sia,” who, at the time, had just been on a Zero 7 album. So we wrote about it. We premiered Odd Future tracks because Tyler, the Creator would send me these weird emails with his capital writing. I was just like, “Who is this weird 18-year-old? But these songs are fire, so let’s put ‘em up.” It was about reading weird emails from 18-year-olds. And then they become famous. We were mostly focused on the magazine, so the blogging was free-range. It was so much fun.

SAM HOCKLEY-SMITH: There was a period where I was running rampant making these awful JPEGs based on what I imagined a song would sound like. I’d be like, “This Rick Ross song sounds like dolphins are jumping over his head.” And I’m not good at Photoshop, so I’d sort of cut out half of his body and find a stock image of dolphins.

ALEX WAGNER: I always thought we were creating FADER for someone out there who is like us, who may have been a unicorn! I mean there was no concrete evidence we had that this person existed but we really wanted them to, and we did not want to disappoint this person.

On the roof of The FADER’s 23rd street offices in 2002.

Kai Regan

On the roof of The FADER’s 23rd street offices in 2002.

Kai Regan

NAOMI ZEICHNER (editor-in-chief): As a reader, I was into the website before I was into the magazine. I was at college reading art history papers, super frustrated with how badly academics were writing about art. So I’d read a column like Schnipper’s Slept On or Ghetto Palms and feel relieved that the writing was smart and also similar to how I talked. I liked that it was personal. Sam telling you what he got for lunch or Julianne telling you what party she went to—I was living in Portland, Oregon. It was a really boring fucking place. Twitter existed, but it was still new—the experience kids have now, building aspirational Twitter timelines—that didn’t really exist. In 2008, FADER was that: a smart conversation between people you trusted.

MATTHEW SCHNIPPER: When Alex Wagner hired me, she said, “You just like all the weirdo stuff. Just bring that in.” I’d just written a story about free jazz for FADER. They’re like, “Yeah, that’s cool. Just do that.”

ANDY COHN: When 2008 came, 2009 came, the recession hit. It was a huge turning point for the magazine where we did see a lot of competitors going out of business, or going online only and then ultimately going away. I think what we were forced to do was be scrappy, and be really aggressive with building FADER as a brand—not just as a print magazine—but as a brand.

ANTHONY HOLLAND: During that time, a lot of other magazines cut the page size, cut the quality, scrambled to do all this short term stuff that ended up destroying their brands. But we never compromised.

MATTHEW SCHNIPPER: I was 28 when I became the editor. I was fucking terrified. I didn’t have a journalism background. We didn’t have a fact-checking department. We didn’t have a research department. No one told us how to do this. We didn’t have copy editors.

I just learned to trust people who care deeply. Someone like Andrew Nosnitsky, a guy I met in college. We became friends talking about records, going to buy records from weird dudes that we met on Craigslist. He can be a pain in the butt, but he knows better than everybody. I think that was what we looked for in young talent: people who’d just decided that they knew better than everybody.

AMBER BRAVO (former deputy editor): If I’m knee-deep in a 2,000 word feature that I have to edit the day before we’re supposed to ship the magazine—or worse, I’m writing it—and you ask me what it’s like to work at FADER, I’d tell you, it’s a fucking nightmare. But if you ask me again, when I’m on assignment, zooming through the streets of Paris in a tiny VW, sitting on the lap of Cat Power, one of my musical idols, I’d tell you it’s a fucking dream.

Eight weeks of Schnipper's Slept On

Matthew Schnipper

Matthew Schnipper

Ho-Mui Wong

Ho-Mui Wong

Alex Frank

Alex Frank

Amber Bravo

Amber Bravo

Maia Stern

Maia Stern

Deidre Dyer

Deidre Dyer

Chioma Nnadi

Chioma Nnadi

Sam Hockley-Smith

Sam Hockley-Smith

“When I started reading FADER, I felt like I’d found a world that made sense and understood me. Now, I just want to make shit that reaches people who haven’t seen FADER before, and get them excited.”—Naomi Zeichner, The FADER’s editor-in-chief.

SAM HOCKLEY-SMITH: For a while, we were not ready to keep up with the internet. When Naomi came on full-time, it started to be a lot about the web. I distinctly remember a shift when talking to publicists. We’d be like, “We can’t fit them in the magazine for this issue, but we would love to interview them for the site.” And they’d be kind of disappointed. But I remember a shift when that stopped mattering.

MATTHEW SCHNIPPER: It was like learning to drive while you were in the car by yourself going really fast, which is real terrifying and also very thrilling at the same time. MP3 blogs first, then Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat. All these things enabled us to hear a lot of music we hadn’t been able to hear. Things did not have to be printed on a physical piece of media anymore. That meant our access was so much bigger. It was amazing.

NAOMI ZEICHNER: I clearly wanted to get the numbers up—I grew up on the internet, thinking it mattered how far something you shared reached. I wasn’t using clickbait strategies because I didn’t know what those were. I barely knew how to use a comma. I just knew what resonated. I wanted to get weed recipes on the site. I wanted Alley Boy to talk to me about why he was mad at Jeezy. I did a bunch of Wiz Khalifa stuff.

MATTHEW SCHNIPPER: I think a lot of change has come from social media. Artists being able to talk to people as much as you want in a million different forms—I think that makes what FADER does a little bit more special.

JASON NOCITO: Around 2010 is when it started to change. Around when Odd Future popped up on the radar. They had created so much content, and really good content. Their books are amazing. Everything they’ve done is kind of amazing. In a lot of ways, they didn’t need me, they didn’t need my photos. When I shot them, they were just so self-aware.

JON CARAMANICA: It’s the magazine that outlasted a bunch of the ones that planted flags in culture. Because if you planted a flag in indie rock culture in the ’90s, it’s crickets for you in 2015.

Duncan Cooper

Emily Keegin

Duncan Cooper

Emily Keegin

EMILIE FRIEDLANDER (deputy features editor): At times, it’s been really hard to wear all the hats we have to wear here. You always have to be moving your brain at different speeds. Editing a magazine that comes out every two months and writing a blog post that’s going to go viral in 15 minutes are very different things. But when you do that all day, and it’s really hard, nothing is better than leaving work with a bunch of your friends and going to see Skepta perform. You might’ve just spent all day editing and writing and thinking about Skepta, but to see him in the sweatiest tiny concert venue ever with everyone else from FADER, that’s how it all makes sense.

NICK BARAT: It’s almost like I’m jealous of how together everything is now. “Damn you all have staff, the website is really tight, you understand how to maximize views on shit.” I think that that’s really special. But I love that the attitude remains the same. Stuff like the Kacey Musgraves cover, that’s an ill curveball, that’s the kind of attitude that we were bringing to covers. I think that the sort of alumni network of FADER people who have gone on to do interesting stuff will always sort of maintain that attitude. It’s a little bit underdog. I wouldn’t go so far as to say it’s chip-on-shoulder, but it’s definitely this attitude of we’re going to prove something. And do it for the right reasons.

NAOMI ZEICHNER: On the 2015 music internet, Spotify can tell you which songs you’ll like and brands make video content with the tiniest DJs from the most remote places. It’s almost impossible to be early or have strange taste. Everybody wants to be weird. So the best way we can distinguish ourselves now, I think, is just to tell stories with a little more rigor, or a little more expertise. We have to make sure our writers are better than everybody else’s, that our editing is on point, that the fact check is thorough. We have to train each other to respond fast and also report with patience and respect. It’s not easy at all—some days it feels basically impossible. When I started reading FADER, I felt like I’d found a world that made sense and understood me. Now, I just want to make shit that reaches people who haven’t seen FADER before, and get them excited.

ALEX WAGNER: We never felt constricted, and that’s really powerful. To be going from an idea about underground rock in Beijing, and then to be in Beijing, writing that story at, like, 3:00 a.m.—I remember thinking, like, How the fuck did I get here? Once you work at FADER, it is hard to work at another magazine.

MATTHEW SCHNIPPER: No one told us how to do this. All my lessons were learned within the square of the FADER office. There wasn’t time or money to go and spend to get that experience, so we gave it to ourselves. It isn’t perfect. But it worked.

PETE MACIA: I miss a ton of it. I miss that stupid office more than anything. Just jokes all day long. You could go in there and feel better about life. That’s what I miss most. I miss wanting to go out and do that stuff with those particular people—everyone was just so excited to go out and find new things and talk about new things.

ALEX WAGNER: It just comes down to people that are curious about the world and kind of get it. The editorial staff was so diverse. Someone can be really different from you, but you can understand that they are curious about the world—you can just tell. It wasn’t like certain magazines where there’s a look and a feel and a style and everybody sort of conforms to that. We were all legitimately into different things. If there’s one lesson that I learned at FADER, I think that people who find themselves at executive level positions or get really successful forget that there is nothing they have done that wasn’t the result of a lot of other people’s hard work. And I never thought of the magazine as mine. I thought of it as ours. Everybody owns this. It was maybe the best job all of us ever had. How am I ever going to have a group of people that I trust and care about as much these people?