The summer of 2015 ended the moment Serena Williams lost in the semifinals of the U.S. Open, and in the stands, watching it happen, was Drake. He had come to cheer for Serena amid rumors that the two were dating, and he spent most of the match on his feet, clapping with vigor and making intense faces that were projected onto TV screens all over the world.

When the match ended, Drake became the receptacle for all the disbelief and disappointment that was provoked by Serena’s stunning defeat. Within minutes, Twitter alighted with jokes about the “Drake curse,” and soon the hashtag #BlameDrake was trending all over the United States.

Maybe it would have happened to whomever Serena Williams was supposedly dating at the time—with a historic Grand Slam on the line, the stakes were high, and the need for a scapegoat was profound. But something about the hostility Drake faced after the match felt tailor-made for Aubrey Graham, and not unrelated to the summer-long winning streak he had been enjoying at the time of Serena’s loss. The reaction confirmed what had already started to become obvious: that Drake, a rapper who was once best known for being a Canadian child star working in a genre where he didn’t quite fit in, was no longer any kind of underdog. Instead, he had become a target, the kind of cultural giant who inspires love and derision in equal measure.

On a balmy Tuesday night in August, about a month before that tennis match, Drake sits in a low-lit hotel suite in Toronto, his legs stretched out in front of him and his black Timberlands up on a coffee table. Holding what looks like a glass of Hennessy dressed with huge ice cubes at his side, he’s talking about how he recently started driving himself places again.

“I’ve been deprived of driving for a long time,” he says. “Riding to the studio with a driver and security and stuff, you lose something.”

It used to be that driving to the recording studio was when he would come up with ideas, Drake explains. Cutting it out of his life felt like leaving inspiration on the table.

“That ride was my favorite thing in the world, you know?” he says. “And before that ride, it wasn’t going to the studio, it was going to my girl’s house, or going wherever. Driving was just one of the most pivotal things in my writing life.”

Driving was how Drake put himself in the mindset of the people he imagined listening to him. When he was trying to figure out if a song was working, he would picture someone playing it in their car. “Especially on this new record, I just want you to be able to…” he trails off. “Sometimes those drives are heavy, man, depending on what happened where you came from and what’s about to happen where you’re going.”

The new record Drake is talking about is Views From the 6, so named after Toronto, the city that is his birthplace, his muse, and his cause. His reps say the LP doesn’t have a release date yet but will be coming out “imminently,” and like every major release Drake has put out since his 2009 mixtape, So Far Gone, it will be released into a world where more people are paying attention to him than ever before. Starting with that first record, Drake has been leveling up continuously, and with the huge year he has just had, Views will represent the culmination of yet another growth spurt.

To recap: at the start of summer 2014, Drake posted a song called “0-100/The Catch Up” on his SoundCloud page and watched it turn into a runaway hit with barely any official promotion. Then, in February, he released a surprise mixtape called If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late, which was comprised of 17 songs that, at one point, all appeared on Billboard’s 50-song Hot R&B/Hip-Hop chart simultaneously. Six even newer tracks—two of which Drake premiered on the Apple Music radio show that his label, OVO Sound, began hosting this summer as part of a reported $19 million deal—subsequently sneaked into the Hot 100. As we sit down to talk, the only remaining trace of the recent turbulence Drake experienced during an unexpected clash with Meek Mill is a Top 40 hit in the form of “Back to Back,” a diss track Drake released in the midst of the conflagration. And to cap it off, one week after our interview, he’ll fly to Atlanta to record a mixtape with Future called What a Time to Be Alive, which will go on to sell a projected half-million copies in its opening week.

I ask him, as he takes a slow sip of his drink, whether in light of his recent triumphs, he worries at all that he’s had it too easy—whether there’s any risk that he’ll start taking for granted his ability to connect with listeners.

He sounds frankly disgusted with the idea. “I’ve never felt like, ‘Oh, people will bite at anything that’s Drake,’” he says. “I’m just not that guy. I don’t feel that way about any of my music… If it didn’t connect, I would have a huge problem.”

He pauses for a second, then continues, leaning into every word: “I mean, I’m really trying. It’s not like I’m just sitting here, just fuckin’ shooting with my eyes closed. Like, I’m trying. I’m really trying to make music for your life.”

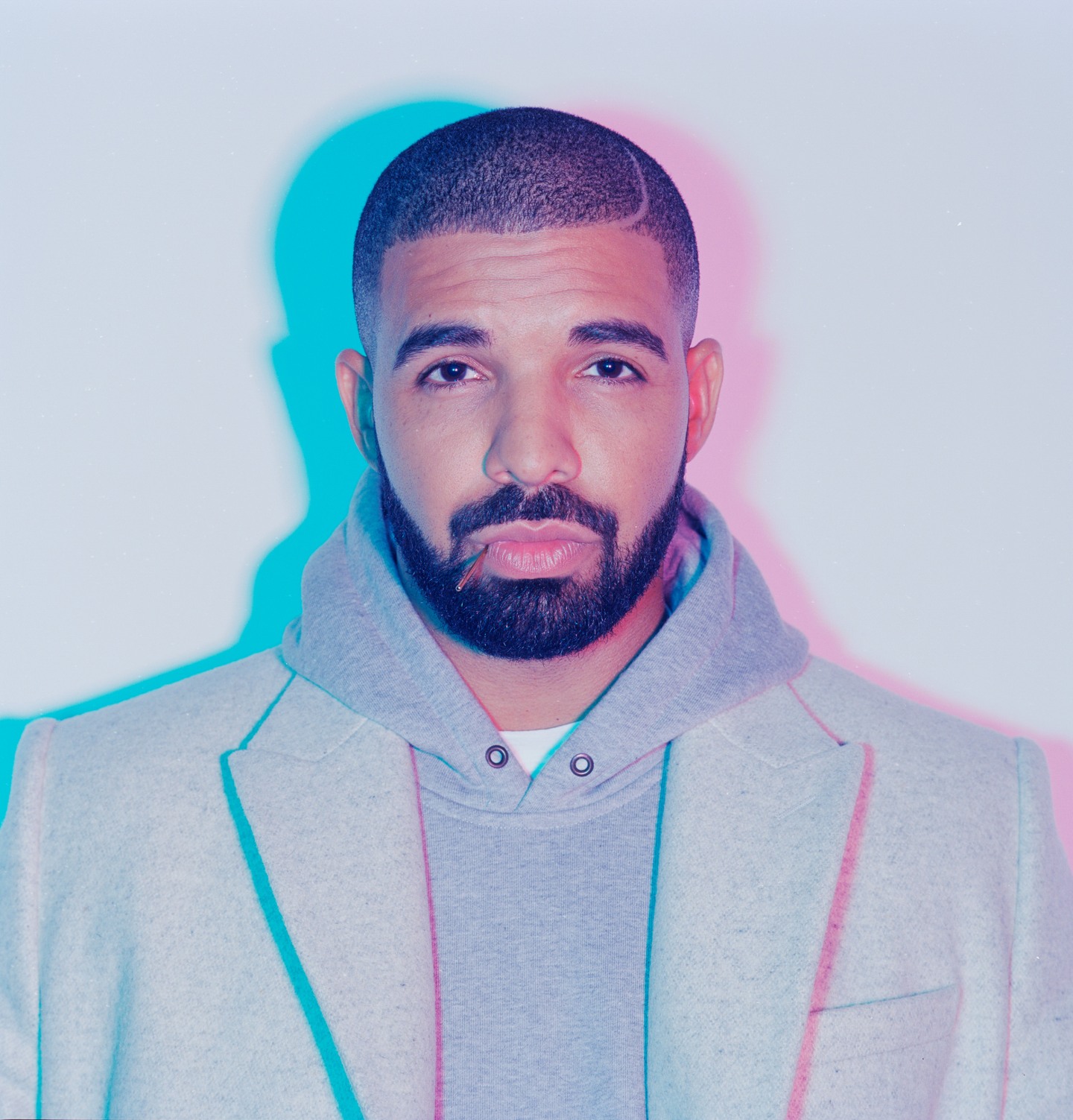

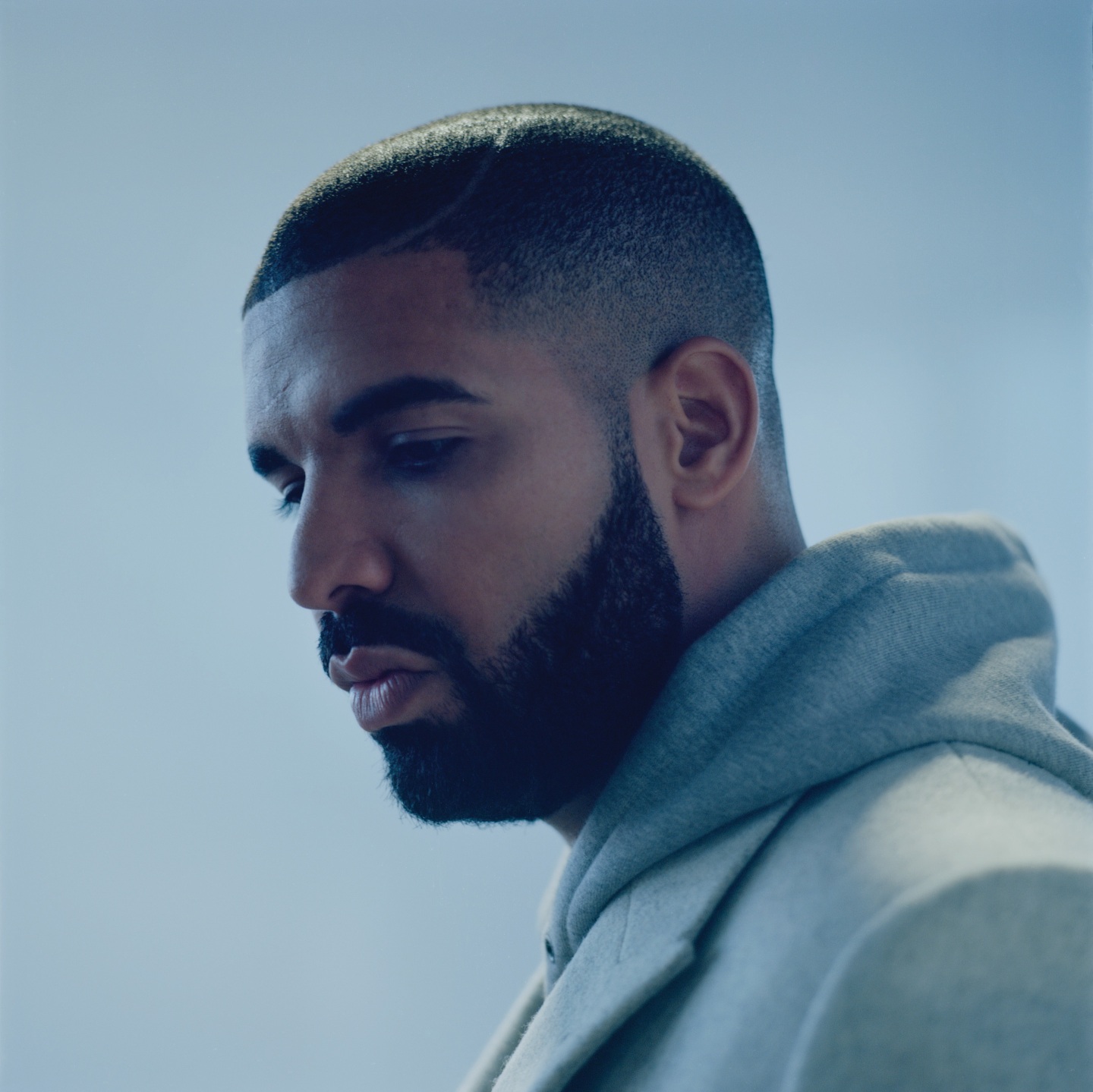

As he says this, Drake projects a practiced but convincing friendliness, and the effort he’s putting into making sure I know he’s being sincere is palpable and disarming. Still, looking at his newly close-shaved hair and the beard that now covers the lower half of his face like armor, I remember the advice he gave recently on one of his songs—Please do not speak to me like I’m that Drake from four years ago/ I’m at a higher place—and make a point of taking it.

This will be the first extended interview Drake has given since Rolling Stone published a story in February of 2014 that moved him to declare on Twitter that he would no longer be talking to magazines. It’s also the first time he has opened himself up to questions about a set of recordings that leaked this summer: so-called reference tracks for songs off If You’re Reading This that suggested Drake had based at least some of his verses on demos composed for him by other people.

By the time we’re done talking, Drake will have addressed those recordings, and opened a window onto the superpowers that allow him, more than almost anyone else in pop, to make music that is new and unfamiliar, but still deeply, widely, and reliably resonant. In the process, he will make a spirited case for collaboration in hip-hop, and put forth a vision of what it takes to make truly original and era-defining art.

“I know everything. I know everything that’s being said about you. I know everything that’s being said about me. I’m very in tune with this life.”

For most of the year, Drake’s focus has been on Views From the 6. Undertaking the high-stakes project, he tells me, required him to hunker down in Toronto in a way he hadn’t really done in a while. After years of constant touring, sneaking in recording sessions whenever he could, and treating Los Angeles as his headquarters, Drake came home and locked in with his longtime engineer and producer, Noah “40” Shebib, the man he forged his sound with, and the friend who has been his closest creative partner since the beginning.

The choice to stay local while working on Views was a response to growing up: at 28, Drake says, he has realized that some of his best friends may no longer be at a point in their lives to “chase me around the globe anymore.” Drake and 40, in particular, have had to renegotiate the terms of their partnership. “We’ve grown a lot over the years,” Drake says. “He used to be the guy that would track me in hotel rooms at 4 a.m. And now he is not that guy—I have another guy that does that.”

He needed 40 for Views, though, he says. “If I want to make the album I want to make, I have to go find him. I have to go sit with him, and we have to really put in effort.”

It’s a marked contrast from the way Drake made What a Time to Be Alive—he and Future recorded it in just six days in Atlanta, working at night, sleeping in the studio, then waking up and working some more, according to Metro Boomin, the tape’s executive producer—and If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late, which was also completed relatively quickly, in three months, and was dominated by beats from Boi-1da and Vinylz. “That was really just me doing one song at a time and just organizing them in an order that I thought sounded really good,” he says of If You’re Reading This. “It was like an offering—that’s what it was. It was just an offering. I just wanted you to have something to start the year off. I wanted to be the first one. I wanted to set it off properly.”

The day before our interview, word came that If You’re Reading This had gone platinum. It was an unbelievable achievement, given that the project came out with no warning and no official single, and that Drake made a point of describing it as a mixtape rather than a proper album. The message seemed to be that it stood apart from the rest of Drake’s catalogue—that it was somehow a lesser work than his proper LPs. When I tell Drake that the tape sounded as cohesive to me as any “real” album I heard this year, he says, “I appreciate the compliment,” but disagrees.

“By the standard I hold myself and 40 to, it’s a bit broken,” he says. “There’s corners cut, in the sense of fluidity and song transition, and just things that we spend weeks and months on that make our albums what they are.”

Perhaps not unlike the Future project, the tape was conceived as a palate cleanser, Drake says—a wild sprint he wanted to get out of his system before turning to the marathon that would be Views. “It was the set up to be able to return to working solely with 40, which is where I’m at now,” he says, explaining that the new album has involved collaborating more intimately with 40 than he has since Take Care. “I just wanted to be able to come back to that and have it be important.”

Toronto to Los Angeles, September 2015

Photography by JJ

Recording Views From the 6 in Toronto has aligned nicely with the arrival of an intense new phase in Drake’s campaign on behalf of his beloved city. That campaign has been going on for years, but the portrait Drake has been painting lately of “the 6” has been more emphatic and textured than ever. It is no longer possible, as it once was, to mistake his local boosterism with a desire to just be from somewhere, nor confuse it with a vain aspiration to bring glory to a city with little pre-existing cachet.

It helps that Drake finally gave Toronto an anthem this year in “Know Yourself,” the standout track on If You’re Reading This that had teenagers and adults all over America chanting about “running through the 6” with their woes.

“I always used to be so envious, man, that Wiz Khalifa had that song ‘Black and Yellow,’ and it was just a song about Pittsburgh,” Drake says. “Like, the world was singing a song about Pittsburgh! And I was just so baffled, as a songwriter, at how you stumbled upon a hit record about Pittsburgh. Like, your city must be elated! They must be so proud. And I told myself, over the duration of my career, I would definitely have a song that strictly belonged to Toronto but that the world embraced. So, ‘Know Yourself’ was a big thing off my checklist.”

What distinguishes Drake’s devotion to Toronto from generic hometown pride is that it comes across as the opposite of provincial. This is a testament to Toronto’s unique cultural diversity: the city’s population is about 50 percent foreign born, with immigrant communities from countries like Jamaica, the Philippines, India, and many others. To be influenced by Toronto, in other words, is to be influenced by cultures from all over the world.

Drake has been channeling those diverse inputs with great enthusiasm lately, most obviously in his use of Toronto-by-way-of-the-Caribbean slang (ting, touching road, talkin’ boasy and gwanin’ wassy) and even religious Arabic words like mashallah and wallahi, a wink to Toronto’s Somali population. “We use [that lingo] every day,” he says, “but it just took me some time to build up the confidence to figure out how to incorporate it into songs. And I’m really happy that I did. I think it’s important for the city to feel like they have a real presence out there.”

The fact that Drake’s not at all worried about alienating non-Toronto fans who don’t know what certain words mean is arguably the true measure of his tire pressure right now. And insofar as he is making Toronto more of an ever-present, fleshed-out character in his music than he used to, it’s because he knows he has the standing to do so. “I’ve just become really adamant about leaving fragments in everything I do that belong strictly to my city,” he says. “The world will pick up on it.”

Though some might see his use of slang as tourism or even appropriation, Drake has forged real-life relationships with artists from scenes based abroad whose influence is felt in Toronto. His admiration for Popcaan, the Jamaican dancehall star, has given rise to an alliance between OVO and Popcaan’s Unruly Gang that resulted in a 22-minute documentary about the OVO team visiting Unruly in Jamaica; later, the patois spoken in that film ended up serving as the source material for dialogue that appeared on If You’re Reading This.

Drake’s interest in the music of London grime MC Skepta, meanwhile, has given him the rare gift of a true companion—not an insignificant thing for the rapper who once proclaimed a “no new friends” policy as a way of dealing with newfound fame. “I was a Skepta fan, but after meeting Skepta… we were brothers immediately,” Drake says. “You don’t get that too much in this thing that we’re in, honestly. You don’t [often] meet somebody and actually feel like, ‘OK, we might actually still talk when we’re 35, 40 years old.’”

Through these affiliations and collaborations—there was also a song with Bachata star Romeo Santos in which Drake sang in Spanish—Drake has become a kind of cultural importer-exporter, or perhaps more accurately, a translator.

“I just want to be remembered as somebody who was himself. Not a product.”

I ask him if part of the motivation behind his international outreach is a desire to build audiences in foreign markets—to become a truly global star, having already conquered North America as much as any rapper ever has. On some level, I ask, is doing a song like this summer’s “Ojuelegba (Remix),” which he recorded with Skepta over a hit single by the popular Nigerian rapper Wizkid, a savvy play for audience share?

Drake is not into this theory. “I just did it because I was in the moment,” he says. “I wasn’t thinking like, ‘Oh man, I gotta get my brand up in Nigeria.’” (He hastens to add, with classic Drake politeness, “Not to say that’s not important. I’m super-honored to be on that song.”)

More than erecting a global tentpole brand, it seems Drake is reaching out for inspiration and new ideas about how a Drake song can sound. On What a Time to Be Alive, you can hear him trying to level with Future as he battles his sorrows with pills and lean, but much of Drake’s other recent output finds him working through influences that actually seem to have brightened him up musically—an almost unthinkable turn of events for an artist whose aesthetic has long been described as cold and wintery. New songs like the tropical-sounding “Hotline Bling” have a gorgeous-sunset quality to them that Drake hasn’t really conjured before; to borrow a metaphor from Lorde, who praised “Hotline Bling” on Twitter recently for its pristine yet evocative simplicity, he is painting with colors—reds, oranges, pinks—he didn’t really used to use.

Drake says this new warmth is not an accident—that he’s making a point of rapping over beats that are a little sunnier than he’s accustomed to in order to see if he can match the level of potency he knows he can achieve when working inside his gauzy, minor-key comfort zone.

“I love dancehall flows, especially as of late,” he says. “I pretty much won’t even rap on a beat unless it’s got some magic element of new tempo or new pocket, where I hear myself and feel like I’ve stumbled upon something new.”

This is Drake’s primary and somewhat paradoxical objective these days: to stumble upon something new, whether it’s a new way to blur the line between singing and rapping or just a new way to render a phrase. “There’s times where I’m sitting around looking for like, three, four words,” he says. “I’m not looking for, like, 80 bars on some ‘5AM,’ ‘Paris Morton’-type shit, you know? There are moments like that, too, but the hardest moments, the most difficult ones, in songwriting, are when you’re looking for like, four words with the right melody and the right cadence. I pray for that. I’ll take that over anything—I’ll take that over sex, partying. Give me that feeling.”

The best feeling of all, he says, is when he finds a whole new flow—a new way to straddle a beat and wrap his vocals around a rhythm in an unexpected way.

“A new flow is absolutely the most crucial discovery in rap, to me,” Drake says. “Honestly, like, I love that I’m sitting here talking to you, but at the same time I don’t, because I want to go to the studio, and I’m praying that 40 has a beat, so that I can do something new that I’ve never done before. That is my main joy in life.”

There’s a moment on “Ojuelegba (Remix)” in which that joy comes through as clearly as it ever has. The breezy, boisterous song, which Drake first heard through Skepta, forces Drake to rap in a way he’s never rapped before, to the extent that it takes him a couple of bars to find the swing of the beat. As soon as he does find it (it happens right as he’s singing Pree me, dem a pree me, Jamaican patois for “they’re watching me”) his vocals and the music click into place, and suddenly the song sounds like it could be a stateside hit.

In that moment Drake reveals one of his most consequential talents: his intuitive ability to bend the new—and thus not-quite-intelligible—into shapes that make sense to millions and millions of people.

We’ll call this his first superpower, and what it allows Drake to do is take idiosyncratic songs that haven’t caught all the way on yet and tune them to a frequency everyone can hear. Most famously, he did this with the Migos flow on his remix of their hit “Versace” and the froggy iLoveMakonnen croon on “Tuesday.” More recently, he did it on “Sweeterman (Remix),” which was originally recorded and released by a 21-year-old from Toronto of Egyptian descent who calls himself Ramriddlz. More of a cover than a remix, Drake’s version of “Sweeterman” captured him in full-on sponge mode, borrowing all of the original’s best features—the tiny melody behind she keeps giving me looks, the word adunana-ne—and tightening them up, while removing Ramriddlz’s voice entirely.

In recording his take on “Sweeterman,” Drake did something he has done repeatedly throughout his career, latching onto a set of charming but off-kilter ideas, running them through his proprietary filter, and shining them down into jewels. By applying his populist instincts to genuinely weird music, Drake has learned new moves, and in exchange for giving up-and-comers the invaluable boost that accompanies his co-sign, he has had the opportunity to introduce one new sound after another into the mainstream. It’s an innovation model, basically: as an artist who is single-mindedly focused on improving and not repeating himself, Drake is serious about staying ahead of the curve, and he approaches it systematically.

When I ask him what makes him want to jump on a song like “Sweeterman,” Drake says something surprising. “It’s just channeling my mom,” he says. “Like, I’d bring home an essay that I did really well on, and my mom would read it through and give me notes back—on the essay that I just scored like 94 on! So sometimes I just do that. I’ll hear people’s stuff and… I’ll just give my interpretation of how I would have done it.”

That’s not meant to be taken offensively, he adds: “It’s just, literally, I’ve recognized the potential and the greatness in this piece, and I want to take my stab at it too—which is kind of what my mom always did, you know? She was just reliving her school days. Like, she just wanted to really write the essay herself. But I had already done it, so she just kind of gave me new paragraphs and sentences and made it better.”

What Drake is describing here, it seems, is craftsmanship and perfectionism. But while those are obviously crucial factors of his success, they wouldn’t count for all that much on their own.

Which is where Drake’s second superpower comes in.

“Music at times can be a collaborative process, you know? Who came up with this, who came up with that—for me, it’s like, I know that it takes me to execute every single thing that I’ve done up until this point. And I’m not ashamed.”

You could call it his emotional imagination. But in fact it’s something more specific: a gift for understanding his fans and intuitively knowing how to activate, and lay claim to, their feelings. Drake is an interpreter, in other words, of the people he is trying to reach—an artist who can write lyrics that wide swaths of listeners will want to take ownership of and hooks that we will all want to sing to ourselves as we walk down the street.

When I ask Drake about how he gets audiences to identify with him in this way, especially now that his life is so extraordinary and strange, he sits up and lays out the elemental chemistry of his music.

“We may be worlds apart in the sense of, you know, where you’re from, where I’m from, what I’m doing, what you’re doing—but what are we talking about?” he says. “We’re talking about very simple human emotions. We’re talking about love, sometimes. We’re talking about triumph, we’re talking about failure, we’re talking about nerves. We’re talking about fear. We’re talking about doubt. It doesn’t matter what you’re doing—you gotta at least hear what I’m saying to you. And I pray that it helps.”

At this he interrupts himself. “Not even ‘helps,’” he says. ‘“Helps’ is a weird word. I don’t ever want to think I’m ‘helping.’ It’s not about helping. It’s more like, even though we’re not carrying on a dialogue, I hear you, you know? And when I make an album, all I want you to know is I hear you.”

You can tell he’s thinking this through as he says it, and as he goes on, it feels kind of like watching someone earnestly arrive at a mission statement on the fly: “Like, I get everything,” he says. “I know everything. I know everything that’s being said about you. I know everything that’s being said about me. I’m very in tune with this life. Much like, I assume, most of my listeners are.”

In this light, listening to Drake’s songs—loving them, internalizing them, feeling #chargedup when you feel like taking a swing at somebody and #worstbehaviour when you’re amped at a party—is a collaborative process between artist and fan. Drake writes songs that encourage that intimacy, and in so doing he consistently finds words for yearnings and aspirations shared by his wildly diverse fanbase. In making hits, he is gifting his listeners those words so that they might express themselves—online, at school, at work, in their own heads—with the benefit of his verve.

On some level, Drake’s ability to do this comes down to his ear for catchy, evocative phrases that are vague enough to be used across many contexts, but specific enough to still feel vivid and personal. But he’s also just good at reading his moment—figuring out what his fans want at any given time and delivering it on schedule.

This sense of timing turned out to be a crucial weapon for Drake this summer when he was pulled into the battle with Meek Mill. Though Drake initially seemed to ignore the surprise attack, it quickly turned into a two-week long demonstration of his skills as an entertainer and his ability to execute on them. In more dramatic fashion than ever, Drake flexed his showmanship, and made fluent use of all the communication channels that are open between him and his fans.

The conflict started when Meek Mill asserted on Twitter that Drake had someone else write his lyrics for him on a verse he had recorded for Meek’s recent album. It escalated when Hot 97 DJ Funkmaster Flex boasted that someone in Drake’s camp had provided him with multiple “reference tracks”—demos, basically, written and recorded by other rappers—that would prove that Drake made a habit of using outside writers.

Drake never spoke about the recordings directly—not even after some of them were made public. But as I prepare to raise the issue during our interview, he catches me off guard by turning to it on his own.

“I’m just gonna bring it up ‘cause it’s important to me,” he says. “I was at a charity kickball game—which we won, by the way—and my brother called me. He was just like, ‘I don’t know if you’re aware, but, yo, they’re trying to end us out here. They’re just spreading, like, propaganda. Where are you? You need to come here.’ So we all circled up at the studio, and sat there as Flex went on the air, and these guys flip-flopped [about how] they were gonna do this, that, and the third.”

He recorded “Charged Up” that very night and released it the next day on the same episode of OVO Radio that saw the debut of “Hotline Bling.” “Given the circumstances, it felt right to just remind people what it is that I do,” Drake says, a proud smile creeping into his face, “in case your opinions were wavering at any point.”

When a reply to “Charged Up” didn’t come, Drake could hardly believe it. “This is a discussion about music, and no one’s putting forth any music?” he says, speaking with a furrowed brow, as if reliving his incredulity. “You guys are gonna leave this for me to do? This is how you want to play it? You guys didn’t think this through at all—nobody? You guys have high-ranking members watching over you. Nobody told you that this was a bad idea, to engage in this and not have something? You’re gonna engage in a conversation about writing music, and delivering music, with me? And not have anything to put forth on the table?”

As the days ticked by and a rebuttal from Meek Mill continued to not materialize, Drake became almost offended at the lack of hustle the other team was putting in. “It was weighing heavy on me,” he says. “I didn’t get it. I didn’t get how there was no strategy on the opposite end. I just didn’t understand. I didn’t understand it because that’s just not how we operate.”

It was then that he decided to just go ahead and do another song. “I was like, ‘I’m gonna probably just finish this.’ And I know how I have to finish it. This has to literally become the song that people want to hear every single night, and it’s gonna be tough to exist during this summer when everybody wants to hear [this] song that isn’t necessarily in your favor.”

That song became “Back to Back,” and in keeping with Drake’s plan, it became an instant radio hit. In the end, Drake never felt compelled to prove his chops in some grand or gimmicky way—by going on a radio show and freestyling, for instance, or putting pictures of his handwritten lyrics on Instagram. Instead he just acted like the leaked recordings didn’t matter. And a few days later, with a performance at OVO Fest—the star-studded concert he puts on every year in Toronto that opened, this time around, with a full-on sendup of his challenger—the whole thing was decisively over, with public opinion overwhelmingly on Drake’s side.

The fact that most of Drake’s fans seemed not to care about the particulars of how his songs were made proved something important: that Drake was no longer just operating as a popular rapper, but as a pop star, full stop, in a category with Beyoncé, Kanye West, Taylor Swift, and the many boundary-pushing mainstream acts from the past that transcended their genres and reached positions of historic influence in culture. At that altitude, it’s well known that the vast majority of great songs are cooked in groups and workshopped before being brought to life by one singular talent. That is the altitude where Drake lives now.

“I need, sometimes, individuals to spark an idea so that I can take off running,” he says. “I don’t mind that. And those recordings—they are what they are. And you can use your own judgment on what they mean to you.”

“There’s not necessarily a context to them,” he adds, when I ask him to provide some. “And I don’t know if I’m really here to even clarify it for you.”

Instead, he tells me he is ready and willing to be the flashpoint for a debate about originality in hip-hop. “If I have to be the vessel for this conversation to be brought up—you know, God forbid we start talking about writing and references and who takes what from where—I’m OK with it being me,” he says.

He then makes a bigger point—one that sums up why the experience of being publicly targeted left him in a position of greater strength than he went into it with: “It’s just, music at times can be a collaborative process, you know? Who came up with this, who came up with that—for me, it’s like, I know that it takes me to execute every single thing that I’ve done up until this point. And I’m not ashamed.”

The victory lap Drake has been on since ending the dispute with Meek Mill has been something to behold—performances of “Back to Back” at concerts that had thousands of people shouting along with the words; the rise of “Hotline Bling” to the Billboard Top 10; the mixtape with Future that had rap fans losing their minds as soon it was rumored to be in the works. It’s a run that testifies to the third and most important thing Drake has going for him: he makes it really, really fun to be a Drake fan.

It’s fun to watch him get better at rapping. It’s fun to follow along with the arc of his prosperity as he clears rungs that were once impossible to imagine him clearing. Now when he releases a song in which he debuts a new flow—or appears on stage at an Apple Music event, or hosts Saturday Night Live, or premieres something exciting on OVO Sound Radio—there are people everywhere feeling happy for him, almost as if being on his team means they themselves have achieved something. (This good will can extend to Drake’s collaborators, too: in an email, Future told The FADER, “Drake is my brother. We have a cool personal relationship, but we have an even better relationship musically,” and Metro Boomin, in a phone interview, recalled the nightly dance-offs that he, Drake, and everyone else involved in What a Time to Be Alive would have in the studio to mixtape-opener “Digital Dash.” After the sessions concluded, Metro said, Drake sent a custom Bape couch to his house for his 22nd birthday.)

Drake’s relationship to his fans, and the mark he wants to leave on the world they live in, is something he has addressed more than once in his songs. I’m on a mission trying to shift the culture, as he put it on “Tuscan Leather.” Or, as he rapped on “From Time,” I want to take it deeper than money, pussy, vacation/ And influence a generation that’s lacking in patience. When I ask Drake what it would mean to actually do those things, I half-expect him to say something about getting young people to realize that the internet is ruining their ability to lead authentic lives. It’s a technophobic stance that he has hinted at before—even as he has demonstrated, over and over, an utterly fluent understanding of digital culture and how to harness it. But instead of being preachy in response to my question, Drake once again brings up his parents.

They’re what he thinks about when he pictures his legacy, he says—the way his mom talks about the songs she listened to as a young woman on a memorable trip to Italy, or how his dad describes the first time he saw The Rolling Stones. “I just want to be a time-marker for my generation,” Drake says. “Whatever my generation is—I’m 28, but I feel like maybe there’s kids right now, who are 16, that might still grow up with Drake.”

His choice of words here is revealing: Drake wants people to feel like they’ve grown up with him, like they know him and see him as a human being who is a part of their lives. “I watch other artists from the past in awe—in awe of the preparation it must have taken to, like, be that individual—the grandiose production of [it],” he says. “And I’ve sort of gotten by just being myself.”

That, more than anything, Drake tells me, is the mark he hopes to leave: “I just want to be remembered as somebody who was himself,” he tells me. “Not a product.”

It’s not a risk-free proposition. Because the truth is, people don’t like it when their friends change, and since Drake is intent on evolving, it’s inevitable that some fans will start identifying less with him and more with the spurned allies and ex-girlfriends whom he describes in his pettiest songs—the people in his life who resent him for drifting away from them or getting so big for his britches. The tough, guarded tone Drake took on If You’re Reading This has undoubtedly cost him the loyalty of some who were attached to the softer kind of openness that he became famous for—and his growing dominance as a star surely contributes to the type of Twitter fury he faced during the U.S. Open, and the glee with which some critics declared What a Time to Be Alive would have been better as a solo Future project.

Drake has acknowledged that the change in him is real. In “You & the 6,” the emotional centerpiece of If You’re Reading This, he talks to his mom on the phone, trying to explain to her how his life is different now, and how people around him are trying to undermine him because of his status. “I can’t be out here being vulnerable, mama,” he tells her.

As our interview wraps up, I ask Drake whether he actually feels that way—and what he imagines he will be, in the Views From the 6 era and beyond, if he toughens up so much that he loses the approachability that has always distinguished him.

“It’s never about toughening up. I don’t even know if that’s, like, cool, being tough and shit,” he says. “Not being vulnerable is never gonna be my thing. I’m always going to share with you what’s going on in my life.”

What has changed, he explains, is that he doesn’t have any doubts left about how good he is, or whether he deserves the spot he has fought to secure since emerging into the public consciousness six years ago as a beguiling, expressive misfit.

“Vulnerability, to me, sometimes comes in the form of being naïve about where I am in the pecking order of all this,” he says. “So I think I realize where I’m at now. And I think I realize that I’m gonna have to be OK with not having that many friends that are peers.”

And with that, Drake is out—done talking, and ready, at long last, to head to the studio, where he says he and 40 will be trying to wrap the third verse of a song they initially thought might work as the opener for Views, but now aren’t so sure. Drake seems confident they’ll figure it out though. He’s looking forward to doing the work.

Pre-order a copy of Drake's issue of The FADER now. It's our 100th issue, and it hits newsstands October 27th.

Photographed at the Crystal Ballroom and Vanity Fair Ballroom, OMNI King Edward hotel, Toronto.

Styling by Nicky Orenstein.